Home > Articles > The Archives > Bill Monroe in the Studio—Recording the Grammy Winner

Bill Monroe in the Studio—Recording the Grammy Winner

Photos by Raymond Huffmaster

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

April 1989, Volume 23, Number 10

Bluegrass music as played by Bill Monroe is like no other sound on earth—and setting it on tape is like no other recording session.

The sounds of bagpipes, blues, mountain churches and running brooks are echoed in Monroe’s tunes—it’s not necessarily music composed with the studio in mind.

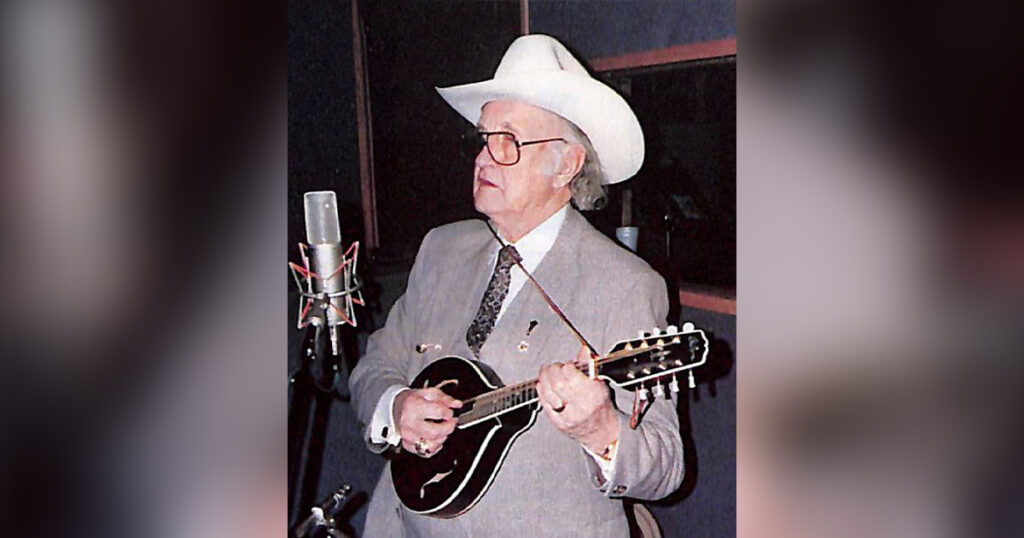

“I write for the music and for the sound,” Monroe said during sessions for his “Southern Flavor” LP. “I write all the time when I’m on the road. I can write an instrumental in just a minute.”

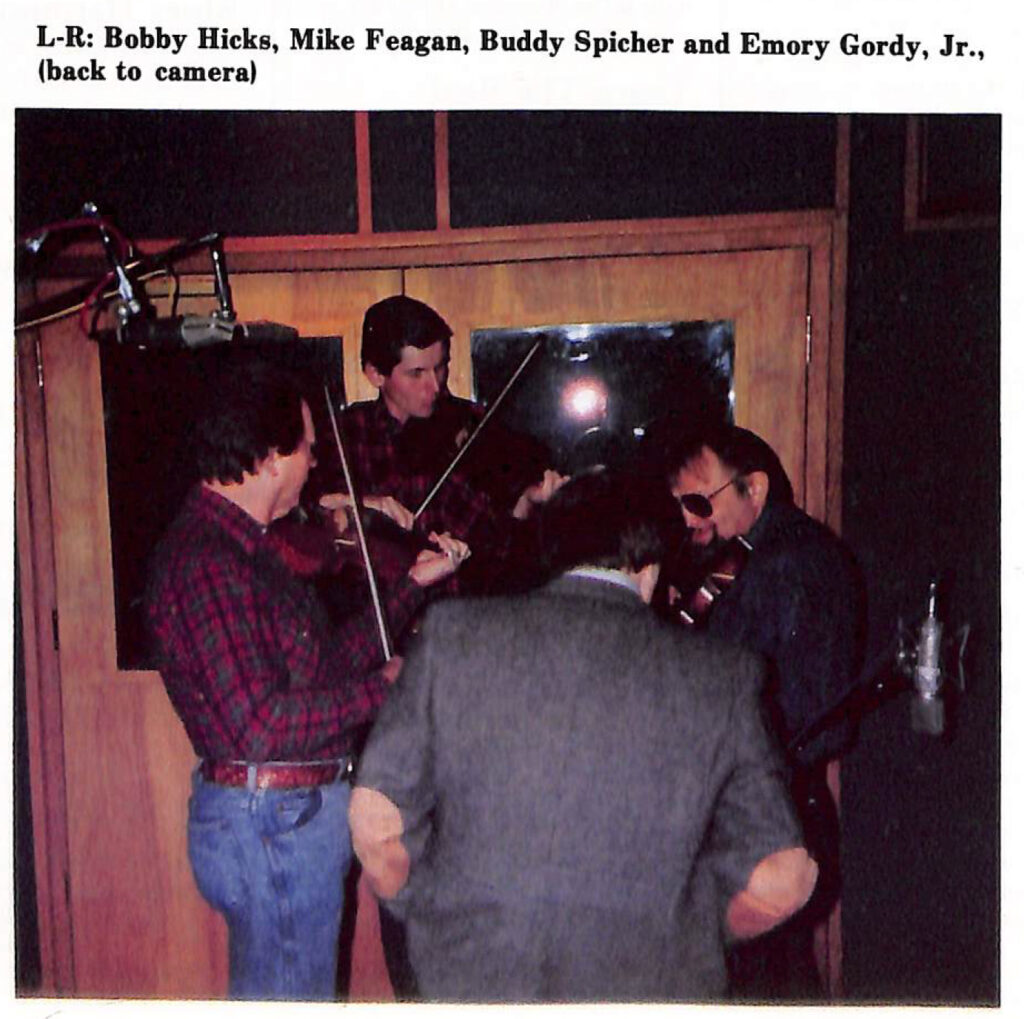

Singer-mandolinist Monroe may come up with his tunes spontaneously, but the often startling contours of his music required all the attention of the players gathered for the session at Sound Stage Studios. Joining Bill for the recording were Tom Ewing, guitar; Blake Williams, banjo; Tater Tate, bass; Mike Feagan, fiddle; as well as ace fiddlers Buddy Spicher and Bobby Hicks.

“People don’t realize it, but bluegrass is hard,” Hicks said while rehearsing a complicated tune. “There’s nothing to hide behind, there’s no drums.” No electric instruments, synthesizers or drums make appearances at Monroe sessions. However, his latest efforts in tradition- based music are captured by the latest in digital technology.

“It’s more microphone placement than knob-twisting, but that’s the way all recording should be,” engineer Steve Tillisch said about recording Monroe. “You want to set as natural a sound as possible on each instrument.”

In the small room where the musicians were playing, bluegrass sounded like chamber music. Every note played by each instrument was clear and distinct, not strident, yet the whole had great rhythmic drive and pulse.

The players heard each other directly, not through the earphones almost universally used in studio sessions.

“As close as we are in here, we don’t need headphones,” said Blue Grass Boy’s bassist Tater Tate. “I don’t hear good, but I can hear in here.”

The first tune on the agenda was an instrumental called “Stone Coal.” “I put that together up in the eastern part of Kentucky,” Monroe said. “Ricky Skaggs and his father were there and his father came up with that name ‘Stone Coal’.”

In the first full run-through of the song, Monroe played the fast-rambling theme, patting his foot all the while, then merely looked at the trio of fiddlers. They erupted into a triple-fiddle version of the tune, just as Monroe had it harmonized on a specially tuned mandolin.

“It’s something I came up with myself,” he said of the cross-tuning. “It’s something like what I used on ‘My Last Days On Earth,’ but it’s different.”

Next, the ball was handed back to Monroe, who got appreciative grins from the other players with a solo consisting mostly of syncopated rhythmic strums across all four strings of the mandolin. That performance didn’t make it on the record, but it woke everybody up.

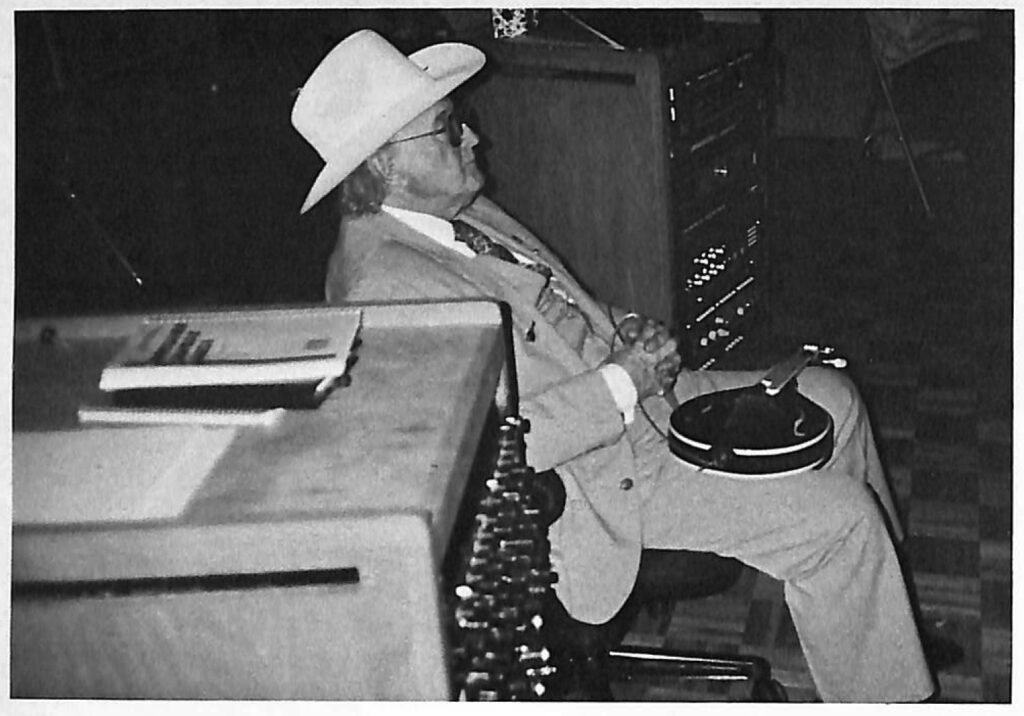

After the first take, or recorded version, everyone filed into the studio’s control room, which looked like the command center of the Starship Enterprise. “That’s a different style of mandolin, isn’t it?” a smiling Monroe said as he came back into the control room.

The informal musicians, clad almost without exception in plaid flannel shirts, were in contrast to Monroe, who wore a western banker’s three-piece suit and hat. They all gathered behind the massive, futuristic mixing console to listen to the take, Monroe patting his feet as if to dance.

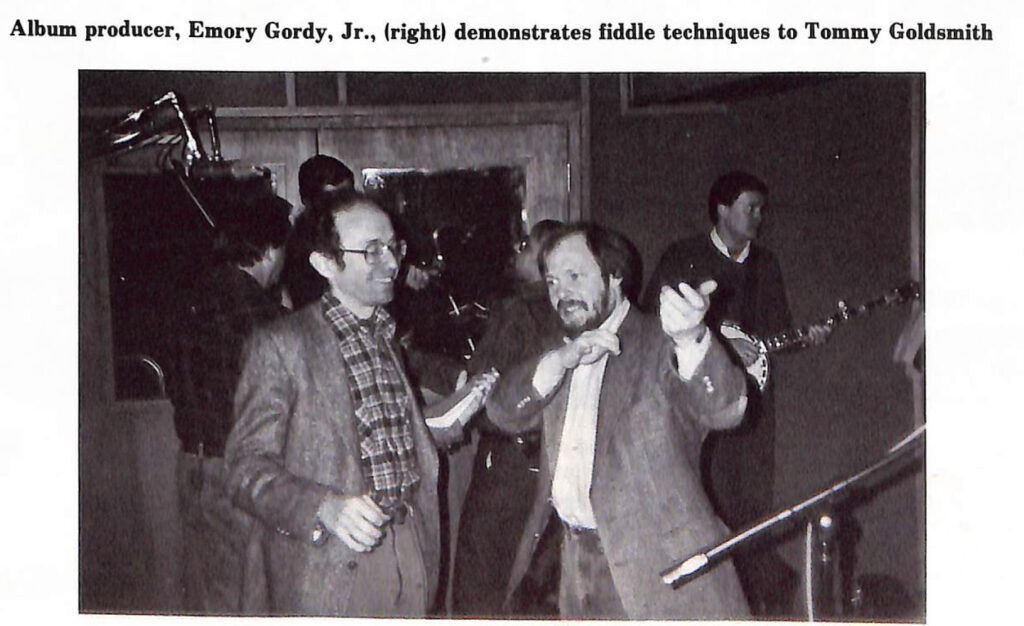

Then they took a minute to iron out fine points of the arrangement. “O.K., let’s see if I can remember,” said producer Emory Gordy. “It starts off with chimes on the mandolin and then Bill does one chorus, then the fiddles, then Bill, then the banjo, then the fiddles come back and he does it again with no bridge.”

Everyone nodded and appeared to take this in. No one made any notes—there wasn’t a written piece of music in sight.

“Right now, you’re all playing kind of tentatively—probably because you’re not comfortable,” Gordy said. “Also, I’ve got a request for the bridge section.”

“We don’t take requests,” Hicks joked, to general amusement.

After the musicians went back in the recording room, Gordy said he typically has Monroe and the band play a song several times over to get the best performance, rather than building a recording piecemeal — “overdubbing” each instrument separately.

“They need to hear each other when they’re playing,” the producer said. “When you overdub, the first guy doesn’t get the benefit of what the second guy does.”

Through speakers in the recording room he said, “All right, we’re going to go for four or five takes in a row.” As Monroe and his musicians played his tune over and over, the piece began to take definite shape. All the solos tightened up, as did the rhythm instruments and the ensemble sound of the fiddles.

“Once they get locked in, the tempo’s always the same,” Gordy said. Monroe, accenting his phrases with body English, became more aggressive in his playing, his hand bogging up and down as he picked.

“At his age, he begins to lose energy, so you’ve got to catch it when it’s there,” Gordy said.

But after what was to be the final take, Monroe said, “Was I supposed to do it one more time? Let me do it again.”

Said Gordy: “That other was the last take; this will be the next-to-the- last take.”

After a strong version of “Stone Coal” was committed to tape, everyone took a brief break.

“When we first started recording we just had one microphone,” mused Monroe, who started making records with his brother Charlie in the 1930s. “The old days were awful good days, but we’ve got to move it along.”

After some discussion, Gordy and Monroe decided next to record on another instrumental, “Texas Lone Star.” It’s an intricate, three-part fiddle tune that young fiddler Mike Feagan took a little while to work out with veterans Hicks and Spicher.

Meanwhile, banjoist Blake Williams and guitarist Tom Ewing were honing their parts for the tune, recordings of which took up much of the afternoon. Like several of Monroe’s compositions in recent years, “Texas Lone Star” has a skirling, flowing, minor-keyed sound that seems to recall both his Scottish ancestry and his fondness for Texas fiddle music.

“We could have been playing in Texas when I wrote that,” Monroe said. “It’s just a number that we could play in Texas. One that might have the sound as it might have been played years ago.”