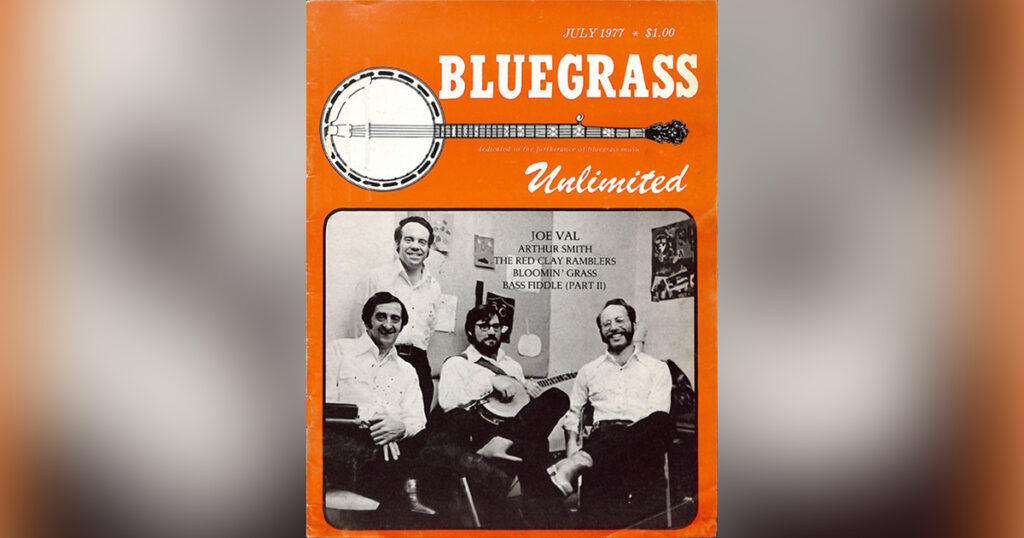

Home > Articles > The Archives > Joe Val and the New England Bluegrass Boys

Joe Val and the New England Bluegrass Boys

By Mike Greenstein

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

July 1977, Volume 12, Number 1

Joe Val and the New England Bluegrass Boys live in Boston, far removed geographically from the nation’s major bluegrass belt. In style and philosophy, however, this quartet with heavy Yankee accents still speaks the language of the bluegrass mainstream.

Unlike many of the Northeastern and Western bluegrass groups which freely integrate other musical forms into their styles the New England Bluegrass Boys remain strict traditionalists, emphasizing an old-timey sound, particularly in their vocal arrangements. “We wanted to have a group that emphasized tight harmonies and would resurrect songs that were not done a lot,” explained guitarist Dave Dillon. So these unassuming, hardworking Yankees set out to emulate the Louvin Brothers and others with that tight harmony singing.

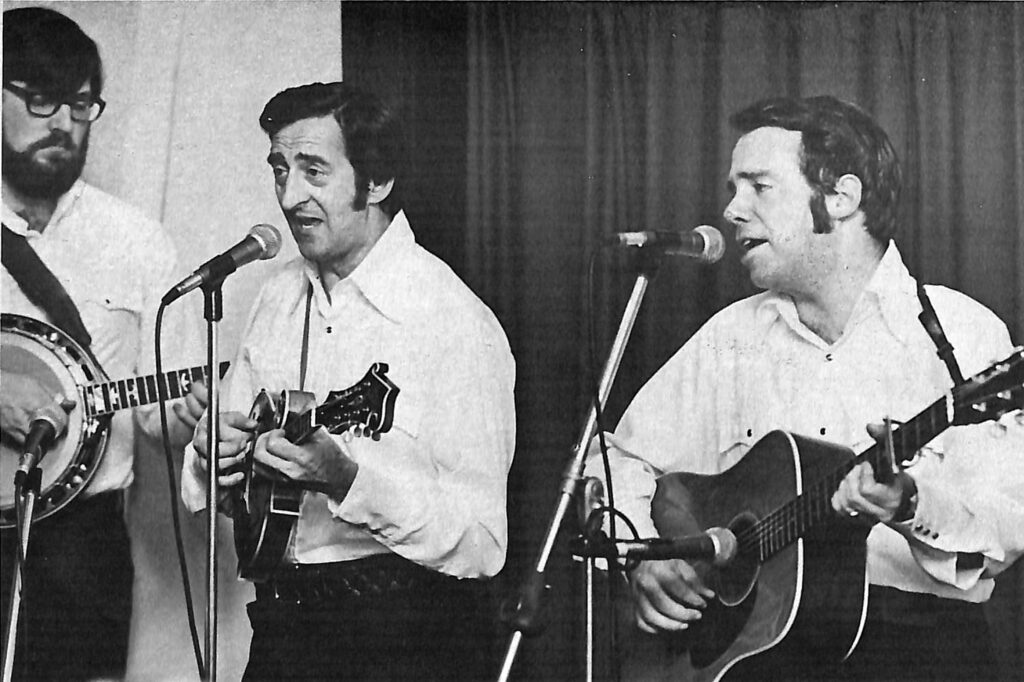

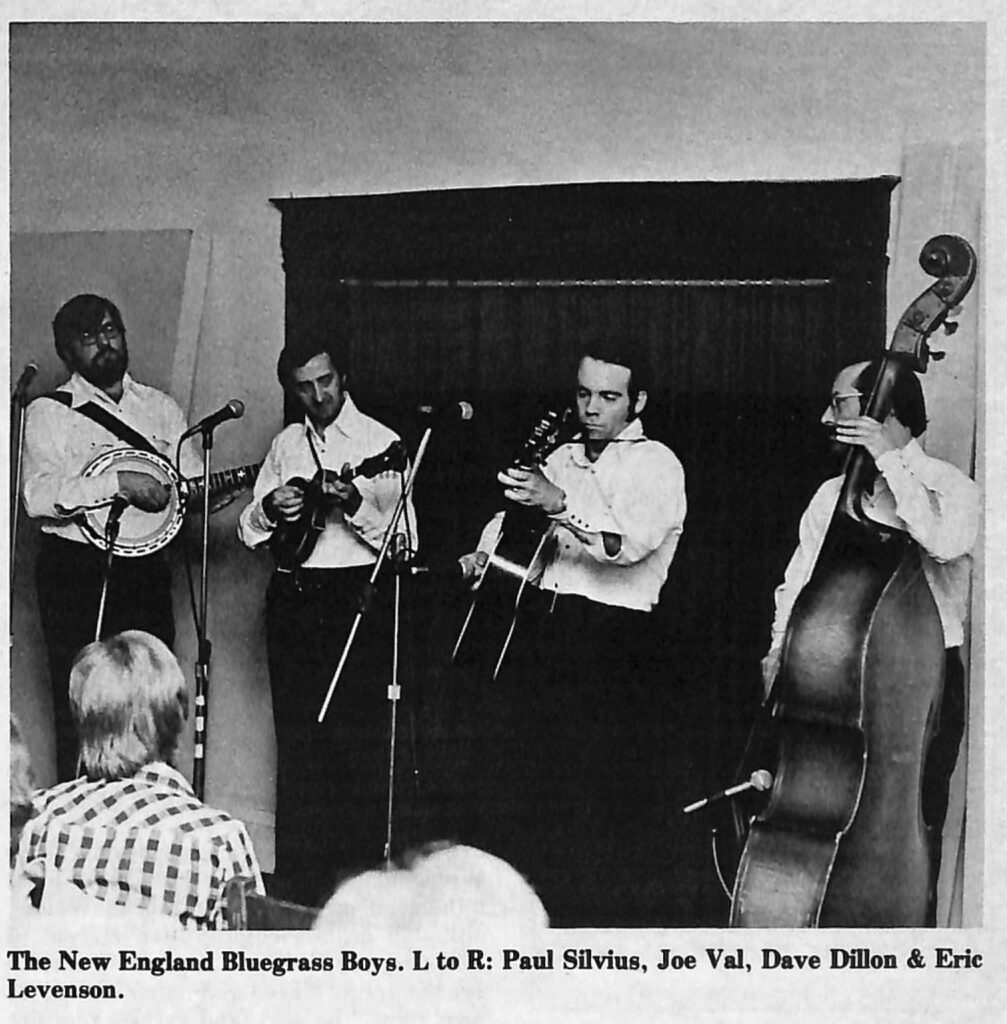

Since they began in 1970, Val and the New England Bluegrass Boys (with several personnel changes) have recorded two albums for the Boston-based Rounder Record Collective (a third will be released shortly) and played virtually every bluegrass festival, coffeehouse and bar in the Northeast. On stage, in their white shirts and black pants, they look like three tiny penguins and a large, bearded, smiling polar bear who completely engulfs his instrument, the banjo. Usually playing standards like “Footprints in the Snow”, “Dark Hollow” (which has particular significance coming from an urban-based band), “Ragtime Annie”, “Grandfather’s Clock” and the Louvin Brothers’ “Born Again” once in a while they’ll vary the format with a Beatles song or something from Merle Haggard and/or Tommy Collin’s (“Sing Me Back Home” or “High on a Hilltop”), but still doing it in their unique old-timey style.

Their distinction lies in their tight two-and three-part harmonies worked out between Val, Dillon and banjo player Paul Silvius. Primarily, however, they rely on the teamwork of Dillon and Val and the leader’s high, high tenor-so high that it’s almost a falsetto at times. He can also yodel in the highest registers.

Instrumentally, the band doesn’t have a dominating soloist, but Silvius on banjo and Val on mandolin more than hold their own on their lead playing, and the guitar/bass (Eric Levenson) rhythm section is extremely solid, always right on top of the changes. The banjo and mandolin supply fills and leads with restraint and good taste, with Val’s mandolin providing another high-pitched counterpart to his vocals.

Val and Dillon have played together only four years, but Val’s introduction to bluegrass came long before. Born Joe Valiante in 1926, Val began playing guitar at 14, starting with country music and first getting interested in bluegrass after hearing some recordings by Bill Monroe.

On a good radio, he could pick up the Opry all the way up in Boston, and he became interested in the music of Jerry and Sky and Tex Logan—who, upon meeting Valiante in the Fifties, shortened his name to Joe Val.

In the early Fifties, the Lilly Brothers and Don Stover came to Boston, and when Val saw them play he was hooked for good. He switched from guitar to banjo and finally to mandolin, and played with a band called the Radio Rangers, which did country and some bluegrass. He became involved in Boston’s growing bluegrass scene at clubs like the Hillbilly Ranch and the Club 47 in Cambridge, where it was rumored his high singing could break glasses. Eventually he played with the Berkshire Mountain Boys and then, in the early Sixties, with guitarist Jim Rooney and banjo virtuoso Bill Keith. With guitarist/vocalist Herb Applin, fiddler Herb Hooven and Val, Keith and Rooney recorded the legendary “Fire on the Mountain” album from Prestige-Folklore.

After that, Val gained further exposure as a member of the Charles River Valley Boys, another Cambridge-based group that recorded an album for Prestige-Folklore before they made their big splash with “Beatle Country”, bluegrass interpretations of hit songs by the influential British rock group, released in 1967 on Elektra. Around the turn of the decade he and Applin, who shared Val’s affinity for the music of vocal duet groups—like the Monroe Brothers, the Callahan Brothers and the Blue Sky Boys—who emphasized tight harmony singing, put together the first version of the New England Bluegrass Boys with Bob French (banjo) and Bob Tidwell (bass) and released their first Rounder album, “One Morning in May” (Rounder 0003, released 1971).

Val’s second release, simply entitled “Joe Val and the New England Bluegrass Boys” (Rounder 0025) was compiled over an extended amount of time, and so had varied personnel. Included were members of the original band, Herb Hooven on fiddle, Bill Hall on banjo and, finally and convincingly, Dillon on guitar. “The big change came when I met Dave,” said the thin, starkly-featured Val.

Dillon, 32, from one of the Boston suburbs, would go to hear Keith and Rooney and the Charles River Valley Boys at the Club 47 when he was in high school. It wasn’t until several years later, however, while a graduate student at Boston University (he now holds a Ph.D. in sociology), that he joined his first regular bluegrass band, the Hudson Valley Boys. Don Stover heard him play with that band and asked him to play with his own band, beginning an association that lasted three years. In July 1973, when Applin went on a vacation, Dillon (then with the White Oak Mountain Boys) filled in. One week after he joined the band, they played the Berryville Festival, one of their few Southern appearances, and the close musical rapport between Dillon and Val became readily evident. When Applin returned, the two guitarists switched bands, with Applin going over to the White Oak Mountain Boys and Dillon remaining with Val.

Dillon, who sometimes drives a cab to supplement his wages, has been most influenced on guitar by Charlie Waller, although acknowledging John Herald of The Greenbriar Boys, as well. “I like to see the guitar played and identified in its own right,” he said, and carries this out with powerful rhythm playing and forceful leads, like the one on “My Old Kentucky Home”, an original tune on the group’s second album.

The current band’s other members both joined in 1976. Silvius, 22, had worked with bassist Levenson in other bands, and his playing was familiar to Val and Dillon before they asked him to join. Classically trained as a singer and instrumentalist, his mother is a voice teacher trained at New York City’s famed Julliard School of Music. “She’s just getting used to the idea that I’m playing bluegrass,” Silvius said with a smile. “Actually, I decided to play bluegrass because I like cowboy boots.”

Levenson, 34, is originally from New York City, but emigrated northward to Boston 17 years ago. In addition to his musical prowess, he is a stage designer, teaches at Wellesley College and is the photographer for many Boston-area musicians and theatre groups. He also handles public relations for the band, preparing what he calls “de press kits”.

Although there are at least a dozen bluegrass bands around the Boston area at any one time, Val’s group is the only one that has developed a sense of continuity and a following outside the city. “We’re hoping to become better known, and we’ve achieved it to a degree. Ninety-nine per cent of our jobs aren’t around Boston,” Val said. “But it’s always been a part-time operation. It’s hard to push it past a certain degree.” All band members have day jobs (Val, a typewriter repairman for 35 years, takes a lot of kidding about his), but they have enough flexibility in them that they can get away for long weekends for out-of-town jobs.

Val, however, admits the band could use a good manager. “We probably could work more, but I don’t think it would be more fun,” he explained. “We try to avoid working the real sleazy bar circuit. I did that for 15 years in the Combat Zone (the section of Boston famous for its strip shows and bawdy films). I don’t want to do that anymore.”

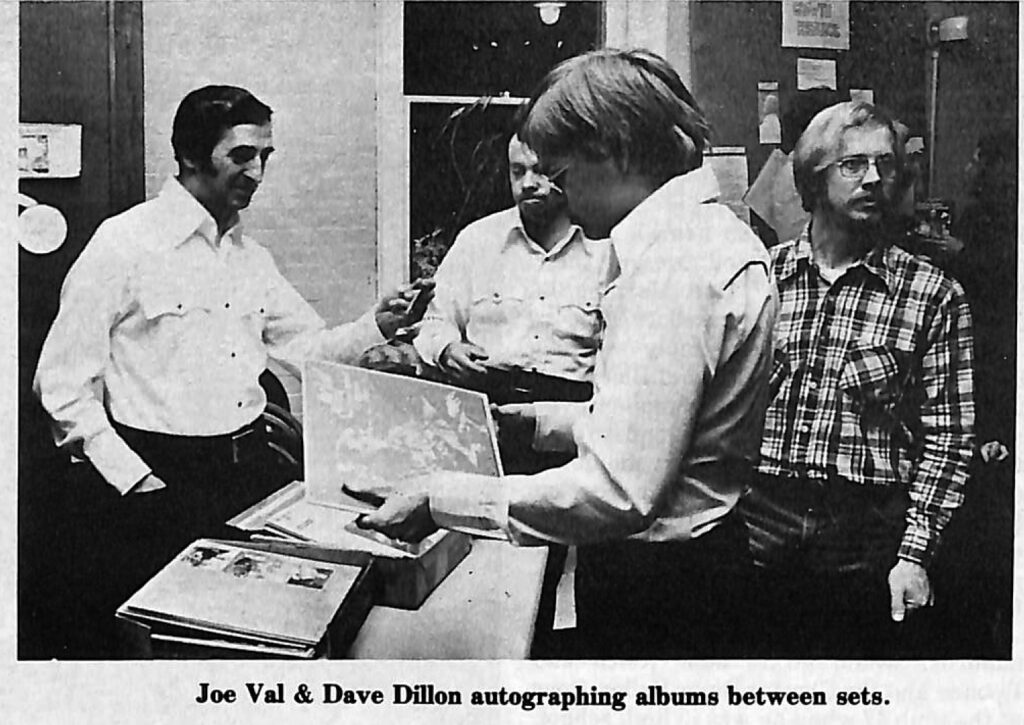

What Val would like to do is play more Southern festivals, since they rarely play south of Delaware. He thinks the band’s tight rhythm and vocal purity would appeal to Southern audiences. Their popularity there and in other regions should be helped by the release in Spring 1977 of their third album, “Not A Word From Home” (Rounder 0082).

John Nagy, who also engineered their second album, recorded this one at a new studio in the Boston suburb of Newton. The album includes some standards, a Beatles song and a Merle Haggard number, meaning it carries a representative sampling of the New England Bluegrass Boys’ usual repertoire. Except for a Dobro player brought in on four of the slower numbers, all the instrumentals and vocals are done by members of the band.

“We’re very happy with the sound and balance,” Val said. “The album has a nice sense of presence that the other albums didn’t have.”

As usual, the soft-spoken mandolinist, whose high wailing vocals (like on “Freight Train Blues”, from their second album) have become his trademark, was speaking too modestly. Joe Val and the New England Bluegrass Boys, while not that well-known outside their home region, play a highly competent, very traditional form of bluegrass that proudly carries on the style and aura of renowned vocal groups like the Louvins and the Stanleys.