Home > Articles > The Archives > Buck Ryan

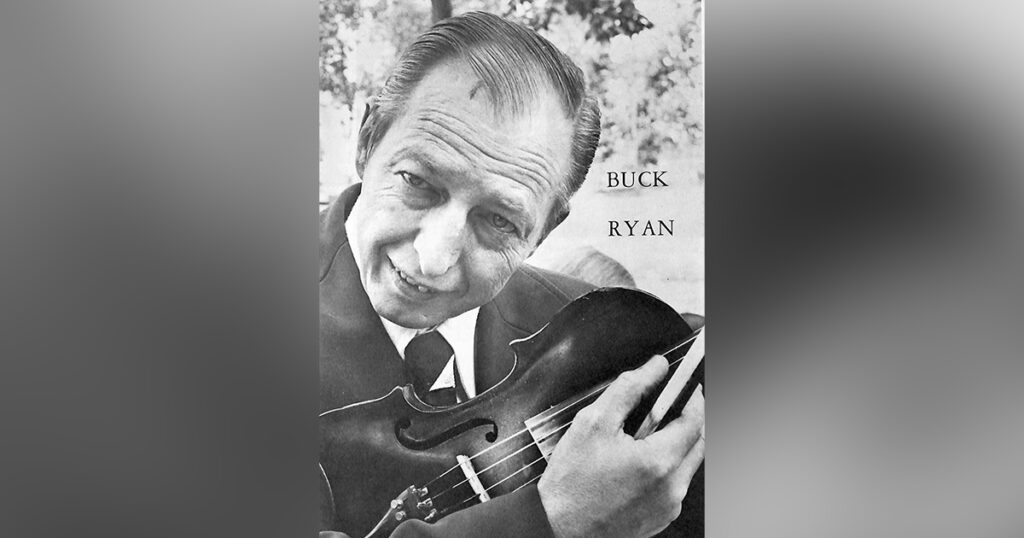

Buck Ryan

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

January 1974, Volume 8, Number 7

The mailbox in front of the neat Fairfax, Va., home bears the name “Arnold Walter Ryan.” But in Jackson, Miss., Bean Blossom, Ind., and Nashville, Tenn., they know the man as “Buck Ryan — World Champion Fiddler.”

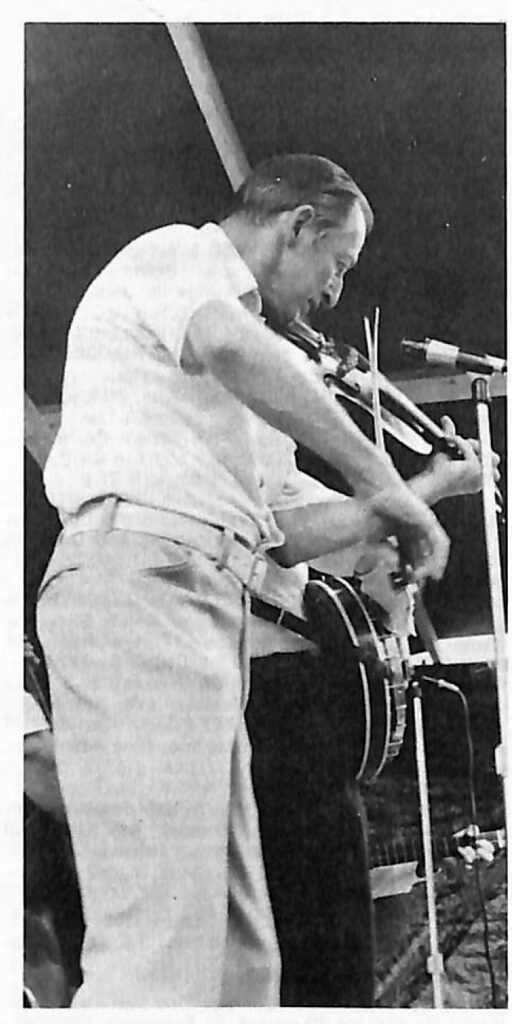

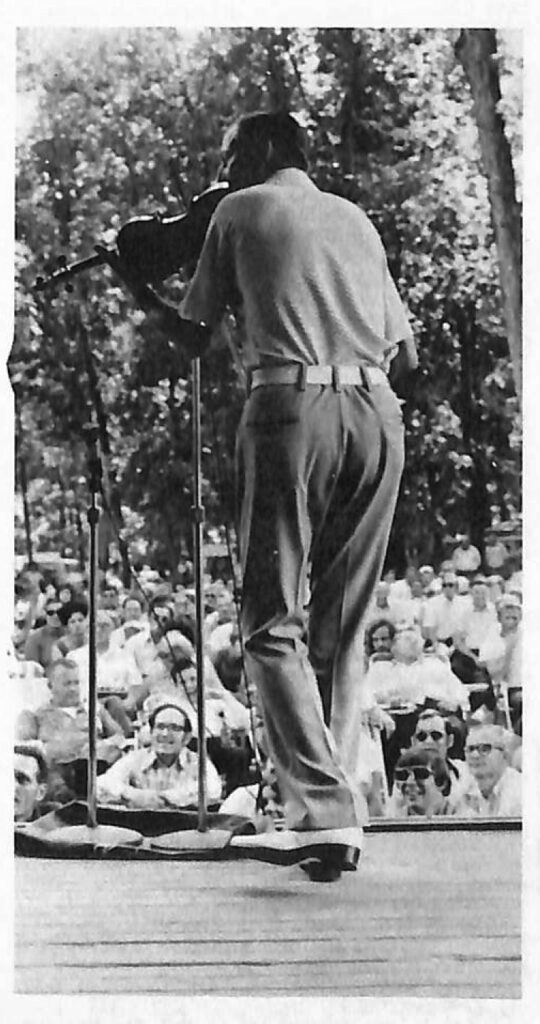

“There’s only one thing as entertaining as listening to Buck play,” a bluegrass fan says. “And that’s watching him play.”

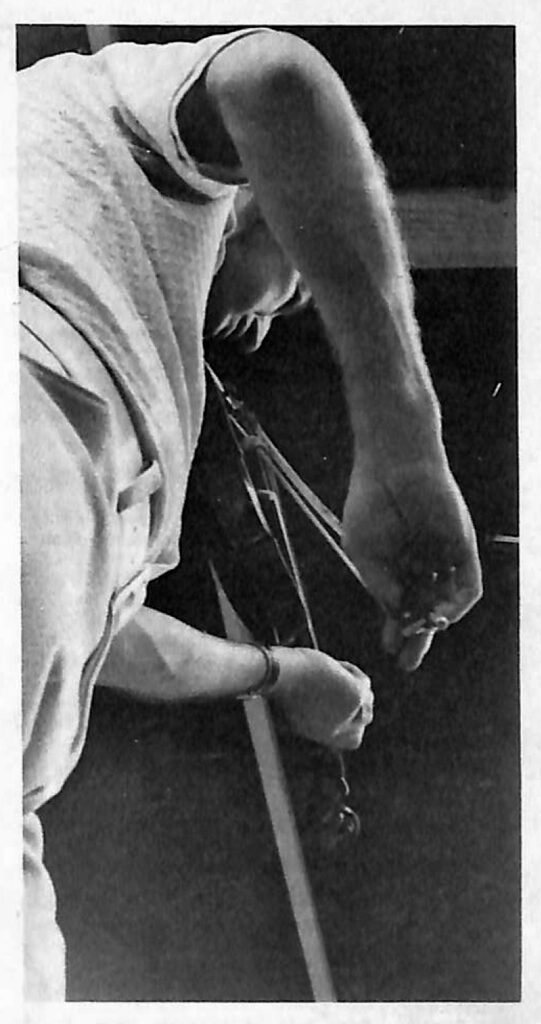

The lanky fiddler (he’s 6 feet, 3 inches tall) can’t stay still when he plays. His wobbly knees almost become rubber. His wrist moves the fiddle bow faster than greased lightning. And the sole of his shoe is warped from toe-tapping.

The road to becoming a four-time world fiddle champion for Buck Ryan has been strange — mostly because few fiddlers have managed to find a way of “earning a living” with their instrument.

Yet Buck Ryan started like almost all fiddlers — as a child. The fiddle was an instrument of influence in his family home at Mt. Jackson, Va. His dad played it at square dances and “Grandpa Ryan” was a music teacher.

One day, when he was 9 years old, Buck Ryan picked up the fiddle and bow and started toying with it. His grandpa noticed his interest.

“Grandpa showed me how to play the scale and I practiced every night by a coal oil lamp,” Ryan said, one day between appearances at this year’s festival in Ottawa, Ohio.

“Grandpa wouldn’t let me put that fiddle down until I got that scale down right. I’d play for hours and hours and it nearly drove everybody crazy.”

The first song he learned to play was “Turkey in tire Straw.” From then on, everything came almost automatically.

Even now, after winning more world fiddling championships in the past 21 years than any other fiddler, Buck Ryan can’t read the first note on a sheet of music. “I just play by ear,” he says. “It’s like clockwork.”

Ryan’s fiddling style won two world titles in Warrenton, Va., — in 1952 and 1962. Then came world titles at Berryville, Va., (Watermelon Park) in 1965 and 1968.

The only reason he hasn’t competed since 1968, is because “I figured if I ever lost a contest, it would be bad publicity.”

In each contest he had to out fiddle 50 to 60 contestants. And he did it by using a bit of strategy. He explains one contest this way: “We all had to play one song and the audience response and judges narrowed it down to 10 fiddlers. “Most of the fiddlers played the ‘Orange Blossom Special’ because it’s such a hot fiddling tune. So I did, too.”

But when it came to playing in the final, Ryan figured the judges were tired of hearing “Orange Blossom Special.” So he switched to his own unique rendition of “Listen to The Mockingbird.”

He’s also known for his “trick fiddling — a thing that’s illegal in the world champion fiddling competition. He can play his fiddle with a toothpick, a bottle, the edge of a shoe or a coat hanger. “Coat hangers work real good,” he says.

Depending on his mood, the 48-year-old Ryan may lie on his back and play the fiddle, or put it under his leg or behind his head and play it. “I’m satisfied being a fiddler,” he says. “If I played another instrument my fiddling would go to pot.”

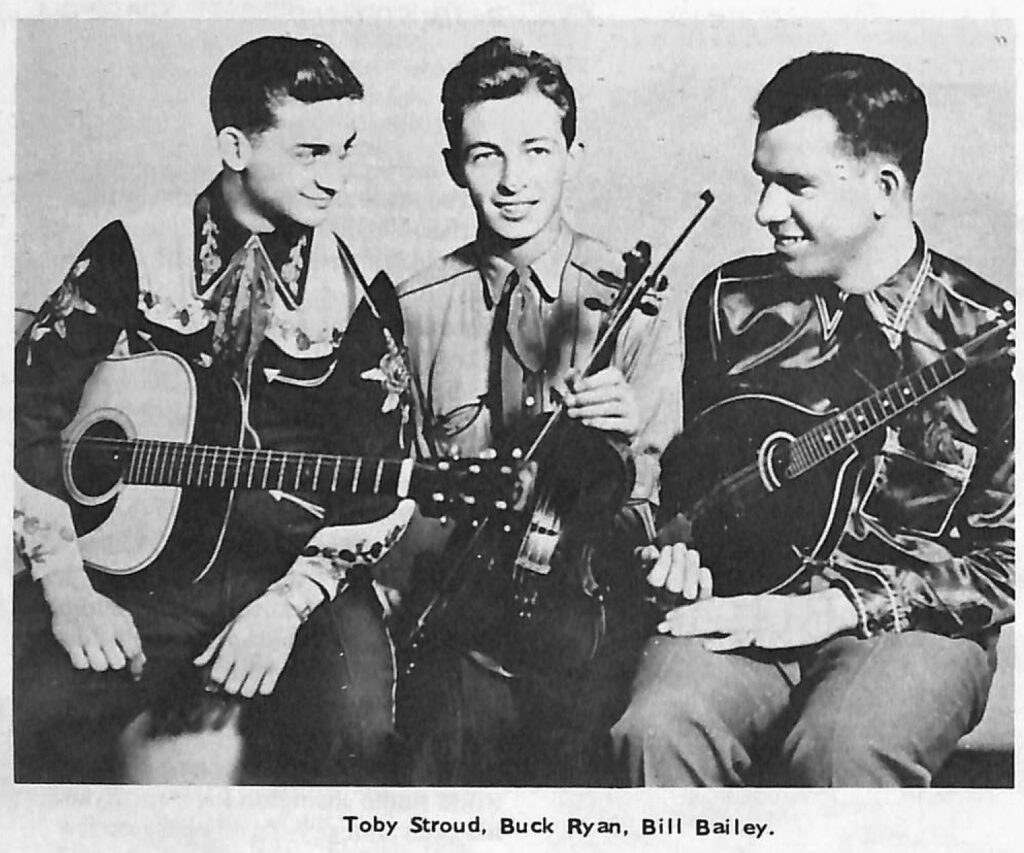

Buck Ryan’s fiddle has always been his only source of income. “I’ve managed to earn a pretty good living with my fiddle,” he says. “I was picking apples at 14 when I got my first job fiddling. I played with a group called Salt and Peanuts on a radio station at Harrisonburg, Va. That’s when I quit picking apples.”

Eventually, like his dad, he joined the square dance circuit, and became “the fiddler” for the “Virginia Barn Dance” — a Saturday night tradition in Richmond, Va. In between, there were a handful of radio appearances, which helped him make just enough money to keep his family going.

He recalls 1946, when things were particularly rough: “My wife was in the hospital and I didn’t have any money to get her out. I was real desperate. I heard about this fiddling contest in Winchester, Va. I entered it and came away with first prize. That money meant a lot. It was something like $500. I was happy to win those world fiddling contests later on, but winning at Winchester when I was flat broke was the happiest contest I ever won.”

In 1956, however, Ryan got a really big break. A new country and western singer named Jimmy Dean discovered Ryan and put him to work as the fiddler for his band, The Texas Wildcats. Ryan was on his way.

“I helped Jimmy cut his first record,” Ryan recalls. “And I finally made it to the Grand Ole Opry stage at Nashville.” Since then Ryan has played with a variety of country bands. There were job offers from such famous country singers as Hank Snow. But for various reasons, Ryan rejected them.

Today he is a big attraction as part of a legendary bluegrass band — Don Reno, Bill Harrell, and The Tennessee Cutups. Their performances have graduated from barnyard stages and square dance halls to college campuses and big city music centers.

This year the group “picked” at such institutions of higher learning as Harvard, Rutgers, Yale, Fordham, NYU, and Lehman College.

At Rutgers, the group drew the largest crowd last year, even beating out the crowds for traditionally famous rock and roll groups. Ryan stole the show with his foot-stomping “Orange Blossom Special.” The audience applauded so wildly when he played it that he had to repeat it three times before the show could go on.

His fiddle also was backed up by the New York Philharmonic when The Tennessee Cutups performed at Lincoln Center before a national television audience this year. It was the first time a bluegrass group had ever performed with the Philharmonic.

The Cutups also recently became the first bluegrass group to perform before the United Nations. In addition the group, recording another first, played at President Nixon’s inaugural ball. (One of the jokes told at bluegrass festivals by Reno, the groups leader, goes like this: “We were the first bluegrass group to perform for an inaugural. Now we may be one of the first to play for an impeachment.)

“They (college students) just eat this stuff up,” Ryan says. “They’re just with you all the way when you’re up there playing. We’ve gotten as high as seven standing ovations from college crowds.” The interest in bluegrass among colleges has developed in the last two years, Ryan thinks. “I don’t know what it is, because they never used to pay any attention to us. But it seems like now they’d rather listen to a good fiddle or 5-string banjo than anything.”

Ryan has five “pet” fiddles. But he usually takes two of his favorites along to performances in an old beat-up blue case. His favorite is a French fiddle he purchased from a fiddle-maker in 1972. “I bought it for $150,” he said. “It has a real clear tone.”

Bluegrass fans think there’s nothing more entertaining than listening and watching Ryan play a hot tune. His gyrating body movements keep time with the beat. One music critic calls him “A bluegrass Brahms.” “You gotta move with this music,” Ryan says. “You just can’t help it. It does something to you. You just can’t be still.”

Inevitably autograph-seekers and fans ask Ryan one question — What’s the difference between a fiddle and violin? “Nothing,” Ryan says. “It’s the person -the player. I can’t play a violin because I can’t read music. A violinist plays in an orchestra and has to be able to read music. But I’ll guarantee you that there’s no violinist that can play bluegrass music unless he was raised on it.”

One important difference he points out, is movement. “A violinist uses elbow action. It’s slow and steady. A fiddler uses his wrist and it’s fast and jerky.” As for how the instrument acquired two names, Ryan has a little tale about that, too. It’s thought that the instrument was first called a violin. But eventually it made its way to the country and mountaineers renamed it the fiddle, he says. “A man’s family could almost be starving and he would be out playing the fiddle, Ryan says. “If somebody asked where he was, they usually said, he’s out fiddlin’ around.”

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

He is one of my hero’s. Who going to fill his shoes.