Home > Articles > The Archives > Greg Cahill and Special Consensus—Taking One Year At A Time

Greg Cahill and Special Consensus—Taking One Year At A Time

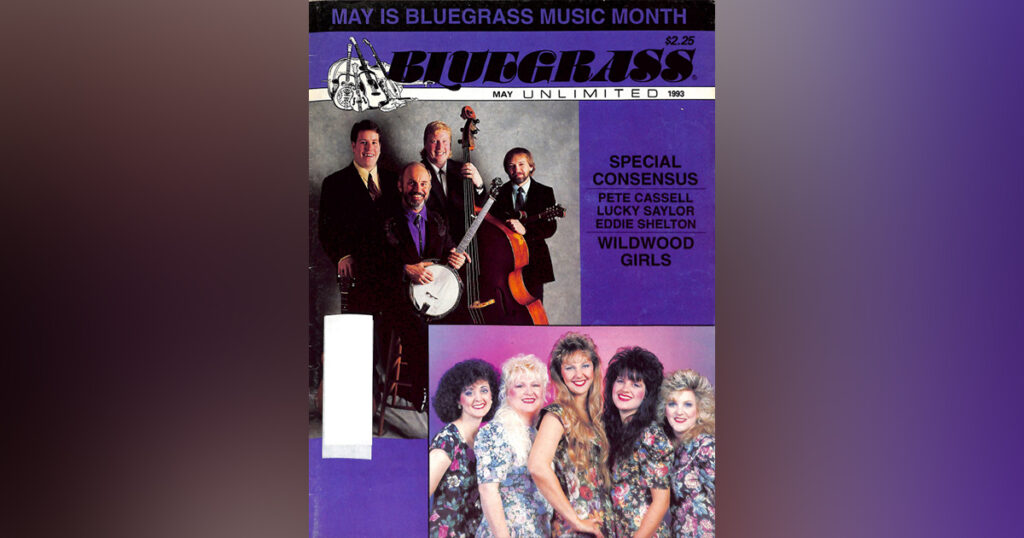

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

May 1993, Volume 27, Number 11

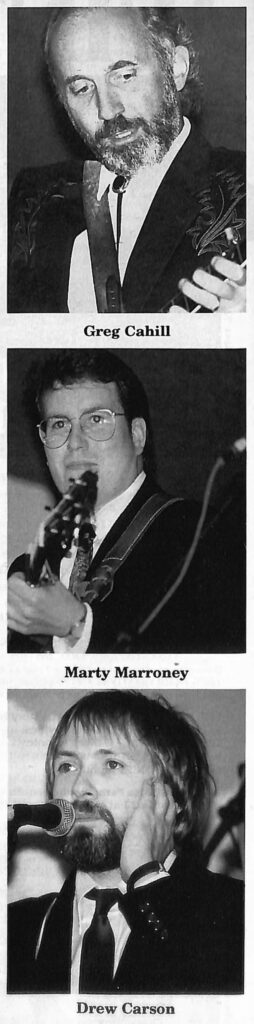

The creases around his eyes cast deeper shadows now and distinguished touches of gray highlight his beard. Gone is the skinny young man who was thrilled to have Byron Berline and Jethro Burns play on his solo album. In his place stands a mature, thoughtful musician who’s paid his dues since 1975, inspiring many younger bluegrass musicians around his native Chicago and wherever he’s played. Over the years, he’s endured endless road trips, a divorce and painful time apart from his young son and lean times where he’s had to stretch money tighter than a banjo fifth string to keep his bills paid.

Despite it all, though, Greg Cahill’s eyes still sparkle with undiluted pleasure as he plays and his ready smile appears as quickly as it ever did. His passion for bluegrass and love for the people involved in the music show in his eager, outgoing performances with his band, Special Consensus. His impact on bluegrass and the broad circle of friends he’s earned over the years shines through as he enters a festival jam session with warm greetings from musicians he’s known during his career. As a band leader, as a banjo player and, most importantly, as a human being, Greg Cahill can only be called a success.

Born December 22, 1946, on Chicago’s Southside into a family which loved music and encouraged its children to play, Gregory James Cahill’s earliest musical experience occurred on his grandfather’s lap. “He used to play harmonica and he would always get a new one for Christmas, so I got his old ones, which usually had a reed missing. And I’d try to play along with him, at least to get the rhythm going,” Cahill recalls.

Living on Chicago’s Southside in the early 1960s, Cahill absorbed his local musical influences much like the great bluegrass musicians of an earlier age absorbed the music they heard in the hills of Kentucky and Virginia. The only difference was that instead of hearing old-time country music on fiddles and banjos, Cahill grew up hearing polka music on accordions.

“On the southwest side of Chicago in the early ’60s, polka music was what was happening,” Cahill explains. “One of my sisters played, so when I started playing accordion we could do duets. We took lessons at the same place and our teacher would arrange duets for us, so that’s how I learned to read music.”

Greg’s father, Bob, was an Irish tenor and his mother Anne played piano, so it was natural for them to encourage their children’s musical interests. Cahill remembers always having lots of music books around his home, providing him with endless material to work out on his accordion. He kept that instrument up throughout his formative years, never dreaming he’d one day make his living as any type of professional musician. But a chance encounter at a high school party rerouted the young Chicago native onto an entirely unexpected path.

“Around the time I graduated from high school, some guy showed up with a five-string banjo at a party after the prom. The folk boom was happening then—Peter, Paul and Mary stuff—and I thought this guy wailing on the five-string banjo was the coolest thing in the world.” Cahill had heard banjo music before on his parent’s collection of records by tenor banjo star Eddie Peabody. But the five-string style was a whole new sound that attracted him in ways the accordion never could.

At college, Greg bought an acoustic guitar ‘Like everybody did” and also wound up trying to learn banjo from Pete Seeger’s famous early banjo instruction book. “I had no idea what the hell I was doing,” Cahill says now with a laugh. But during that period, he heard Flatt & Scruggs’ “Foggy Mountain Banjo,” and like so many other banjo players, his world changed overnight.

“I heard that album and about dropped my teeth! I told my Mom I wanted that album for Christmas and she got it for me,” Cahill says. “I tried to start playing that style, but I was holding my hand all wrong and played sloppy as hell.”

After earning his undergraduate degree in economics at college, Greg had planned to go on to grad school in economics or pursue a law degree. But those plans changed when he received his draft notice and did a tour in the Army, where he was stationed at bases in Missouri and Georgia. “That’s where I heard these guys who really knew how to play banjo,” he remembers. After his discharge in 1970, Cahill returned to Chicago, eventually purchased a Mastertone at an old music store and began taking banjo lessons from Richard Hood of the Greater Chicago Bluegrass Band. It wasn’t long before bluegrass and the banjo had him hooked.

“I spent a lot of time listening and playing with records and by 1974 or ’75. I decided I would take a year off to play music,” he says. “I finally decided I had the bug too bad, so I quit my day job and practiced eight hours a day. I couldn’t get enough. I couldn’t do anything but eat, sleep and drink the banjo. I was listening to old Scruggs and J.D. Crowe records and I never went back. I just kept doing it, squeaking by on no money and practicing a lot. That’s when the band started getting together, just playing for fun and for parties, but then we started traveling and performing more.”

In addition to his overwhelming love of banjo playing and bluegrass music, Cahill credits the writings of Carlos Casteneda, an anthropologist whose books explored the mystical and spiritual beliefs of a Mexican Indian tribe, with helping him make the decision to pursue music fulltime.

“In his books, Casteneda talks about ‘the path with heart,’ and reading those books kind of influenced me to quit my day job,” Cahill says. “I knew this was what I wanted to do and I knew I had to try it.” His band’s name, Special Consensus, also goes back to the Casteneda books.

“The special consensus was a state of mind for the Yaqui Indians where all the good things in life connect with the good things of the spirit. It’s what a lot of people try to achieve when they’re taking drugs, but here it was this natural thing you could connect with if you just kept on the right path, working at it and pursuing what you wanted to do,” he explains.

Since his decision to pursue the ‘path with heart’ in 1975, Cahill has doggedly stuck with a demanding schedule of touring, performing and recording that has gradually earned him recognition as one of the top banjo players and band leaders in bluegrass. Following that path, as every professional bluegrass musician knows by heart, requires total commitment and unwavering desire.

“It was always hard times, especially after I got divorced. I was always sharing apartments and I had my son with me a couple days a week whenever I was in town,” he says. “There were a lot of times when I almost bagged it, but then a festival I’d wanted to play for ten years would come through and I’d go, ‘Okay, I’ll give it just one more year.’ I’ve been ‘one more yearing’ it now since 1975! There were times when I was only making $300 a month and wondering how I was going to get by, but something would always come through at the last minute to pay the rent, so I just kept doing it.”

None of that endurance and perseverance would have been possible, Cahill readily adds, without the help and encouragement of so many people throughout the bluegrass community. “I could never have done this for a minute or even halfway survived if it hadn’t been for all the people involved in this music,” he stresses. “I don’t mean just the musicians, either. I mean the people who’ve let us stay at their houses forever and who’ve helped us along the way. I couldn’t have done this without all the friends and the support of people who would just give you the shirt off their back. They know trying to make a living in bluegrass is hard to do and it’s great because when they know you’re coming through town they’ll call you up and tell you to come on by and stay at their house. It is, for sure, an amazing thing. I don’t think anybody in bluegrass could survive without it.”

Another factor contributing to his endurance and success undoubtedly has been the high quality of musicians Cahill has attracted to his band. Many of the musicians he’s worked with have won national championships on their instruments and have gone on to professional careers with major touring acts. “I’ve definitely been very lucky to attract such good musicians to work with me,” Cahill agrees. “That’s just the result of keeping the faith, I swear. What it boils down to is you treat people the way you want to be treated and it just comes home to roost time and again.”

His latest incarnation of Special Consensus features guitar, acoustic bass and mandolin in addition to Cahill’s banjo.

MARTY MARRONEY

A native of Cape Neddick, Me., Martin James Marroney shares more than his middle name with his band leader. Both started on other instruments before taking up the instrument they play now.

For Marroney, coming from a nonmusical family meant that “this was an accident” for him to become a fulltime bluegrass musician. He’d gotten a guitar as a Christmas present in his early teens and got hooked on bluegrass while attending high school in North Huntington, Pa. There, Marty began playing bluegrass music with a friend whose father played fiddle with Mac Martin and the Dixie Travelers.

“I started to accompany the fiddle and I liked it,” Marroney says now. “That’s when I started singing, too. My mother was the one who gave me a big push in that area. She said someone’s got to sing, because we had a little group going then and it’s gotta be the guitar player because he always sings. So I said okay.”

While moving up and down the East Coast with his parents, Marroney tried to work his way into the bluegrass scene playing with a variety of part-time bands. That exposure helped him meet Cahill, who eventually gave him his first shot at working full-time in a touring bluegrass act.

Marroney, who sings lead and harmony in addition to playing guitar for Special Consensus, cites Tony Rice, Hot Rize, Del McCoury, Bill Monroe and the Johnson Mountain Boys among his biggest influences. He’s also especially happy to be working with Cahill as his first band leader.

“I like playing with Greg because he’s honest and hardworking,” Marroney explains. “We have the same passion for the music. He keeps wanting to do it and to doit right.”

DREW CARSON

Special C’s mandolin player can’t remember when he first developed his love for the music. “I got bluegrass fever a long time ago,” says Drew Carson. Doc Watson was an early influence, leading him on to the Stanley Brothers, Flatt & Scruggs, Monroe and other traditional bluegrass greats.

After starting on guitar at 14 so he could play along with two older brothers, Carson heard a Bill Monroe album and “thought the mandolin sounded tough, so I wanted to get one of those and see what I could do with it.”

For most of his career as a performing musician over the last 12 years, Carson has played guitar and mandolin in local country music bands around his home in Aurora, Ill. Joining Cahill, he adds, has given him his first chance to work with a touring band.

“Traveling is a pain, at least it is for me. You sit and ride all day, then you have to get out and play a lot of fast songs in B!” says Carson with a laugh. He puts up with the trauma of travel because he appreciates the opportunity to work with Cahill and his fellow musicians. “I’ve played enough to know they could play well, but you have to like the people you’re working with because you’re going to be stuck with them,” Carson says.

Band leader Cahill says he’d known Drew a long time and always wanted to have him in the band someday, despite Carson’s reluctance to tour and play music full-time. “It took us a while to convince him he had no choice but to join us,” Cahill says, adding slyly, “We told him we’d break his kneecaps if he didn’t.”

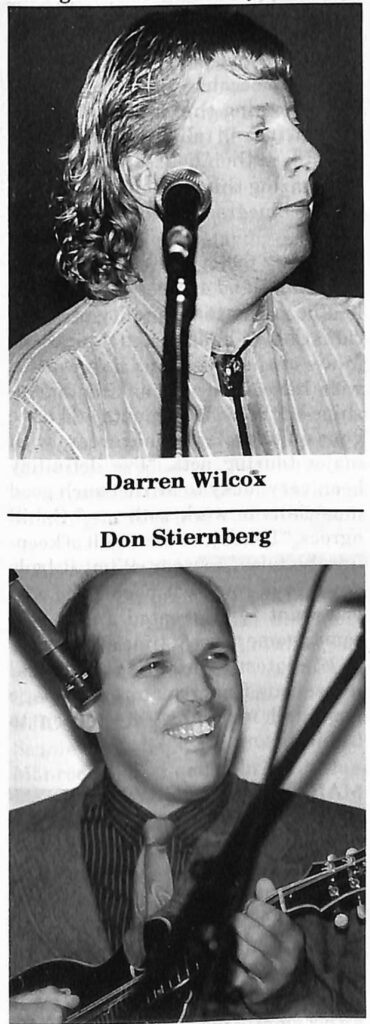

DARREN WILCOX

The son of a tuba-playing father, it’s possible that Darren Wilcox was born to play bass. Born in Newton, Kans., on September 12,1967, Wilcox grew up hearing popular music around the house.

But it wasn’t until he was 16 that he noticed an electric bass in a catalog and jokingly told his parents he wanted it. The bass became his birthday present and young Darren began taking lessons—for about six weeks. “I gave the lessons up and just played along to the radio for a few years.” Then in college, he joined his school’s jazz band because the members needed a bass player and were willing to help him learn. That experience gave him enough confidence on bass to answer a classified ad from a band playing acoustic music.

“I had no idea what that was,” Wilcox says now. “I wasn’t even aware of bluegrass until I started playing with them.” Through playing with Bizarre Crossing, he discovered the music of New Grass Revival and began to fall in love with all bluegrass music styles.

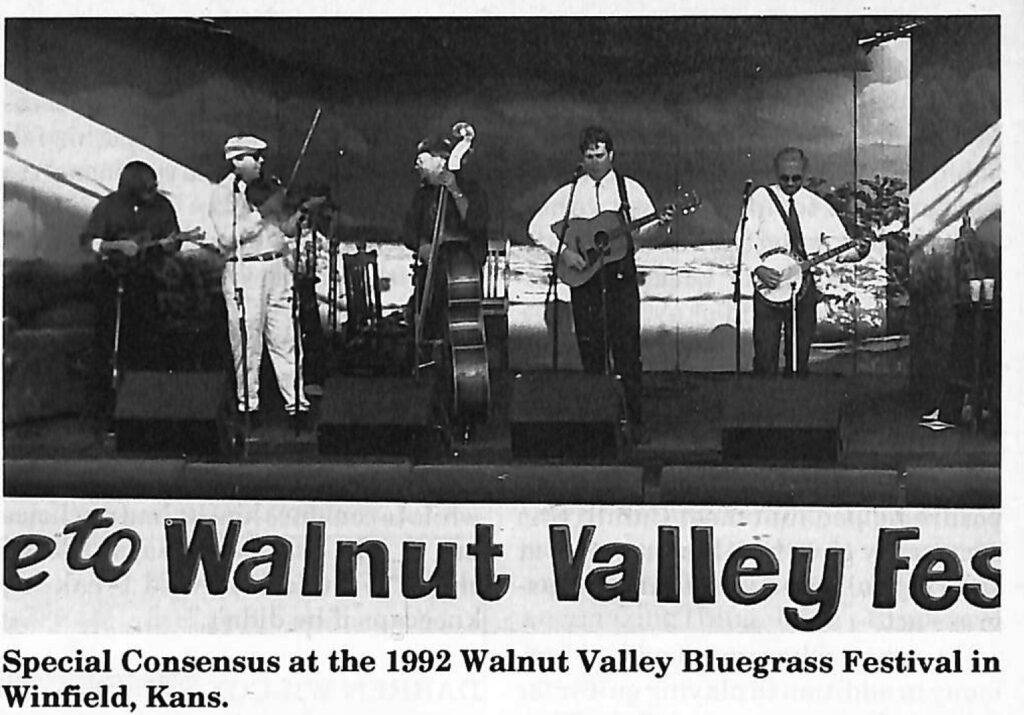

His connection to Cahill and Special Consensus began when his band played right before Special C at a festival in Wichita, Kans. Next year, Cahill jammed with Wilcox’s band several times on an open stage at the Walnut Valley Festival in Winfield, Kans. So when Cahill needed a new bass player and singer, he approached the young Kansas native about moving to Chicago and playing full-time.

“When he asked me if I wanted to join his band, I took it as a compliment, but I never took it too seriously,” Wilcox explains. But at Cahill’s repeated urging, he decided to quit his job as a heating and air conditioning technician and play bluegrass for a living.

DON STIERNBERG

In basketball, teams often keep one highly talented player on the bench instead of using him as a starter. This “sixth man” comes in during critical times to give his team a much-needed push to make them all play better.

The sixth man in Special Consensus is Don Stiernberg, surely one of the most talented mandolinists playing anywhere today. The protege of jazz mandolin giant Jethro Burns, Stiernberg contributes fiddle, mandolin and vocals to the band at many of its Chicago-area gigs. He also has performed with the group at IBMA and many other important festivals.

“I feel glad to be included as a ‘spare part’ in Special Consensus,” quips Stiernberg, who also matches his mandolin mentor’s quick wit in addition to his fluent, unregimented mandolin technique.

“One thing I really like about it, especially now with the lineup Greg has, is that all the guys really love the music,” says the man known to millions of adoring fans as Big Stern. ‘We make a lot of jokes about the difficulties of being a musician on the road, but when we all get together, there’s a lot of time spent discussing how much we love the music, who we listen to and which records excited us.”

An adept, professional musician who can perform on guitar, mandolin and violin in many styles of music, Stiernberg recently collaborated with Cahill on “Blue Skies,” an instrumental CD featuring both musicians performing jazz, bluegrass and other tunes.

That album, along with Cahill’s solo album, “Lone Star” and his other records with Special Consensus, displays the range of musical influences and talent that have made Greg Cahill a major figure in contemporary banjo. He’s been featured in a cover story in Banjo Newsletter, and frequently gives workshops on banjo at the festivals where he plays.

Ever-modest about his own abilities, Greg says he doesn’t see himself as a great banjo technician. “I see so many great players and I don’t consider myself like that, except maybe in terms of playing from the gut. There are certainly better technicians, but I always encourage people to stay musical. I used to try to play all the hot licks in the world and it would just sound bad. Some people can do that and make it sound great, but you really have to take your own sense of the music and trust that.”

Looking back over the 17 years of his own career, Greg Cahill seems almost amazed that he’s survived and continues to enjoy life as a working bluegrass musician. He may finally be reaching that enviable time when the good things of the spirit connect with the good things of life. He now has one of the best-sounding incarnations ever of Special Consensus working with him. A strong new album of mostly original material, “Green Rolling Hills” on Turquoise Records, should be out by the time this article appears. A string of good festival bookings and club dates help him pay the bills. But when he compares his career path with more conventional jobs, he’s also realistic enough to see how the choices he’s made have affected his position in life.

“I’d have a hard time doing anything else now,” he says thoughtfully. “I don’t exactly have a retirement policy, you know. I can pay the bills easier and that’s good. I’m happily married now and that’s nice. I feel good, but I still have to worry about next festival season. It would be nice to have some extra security. I don’t mind working hard, especially when it’s something you love to do. But it would be nice to have some of the security of people who’ve been doing what they do as long as I have. They have benefits and the perks as well as the money.

“For the longest time, I didn’t care about that and I’m still not going to make the pursuit of the buck my lifelong ambition. But as you get old,” he emphasizes, “you start thinking you’ve got to have a little money in the bank and do more than just get by.”

Getting by from one year to the next. For all but a handful of the musicians who’ve devoted their heart and soul and life to bluegrass music, that’s the future they face every day. With the help of friends and fans, promoters and club owners, record companies and radio stations, the musicians who make bluegrass music survive and with them, our music survives.

So the next time you’re at a festival or a record store, remember the Greg Cahills of the world, those musical journeymen whose devotion and honesty, talent and endurance make bluegrass music possible and buy that CD or t-shirt. Offer a warm bed and a homecooked meal to a lonely band on the road. Call your local radio station and ask them to play more bluegrass.

Maybe then we can keep convincing Greg Cahill and Special Consensus to keep at it “just one more year” for many more years to come.