Home > Articles > The Archives > Blue Side of the Mountain—Steel Drivers Mine A Deeper Vein of Lonesome

Blue Side of the Mountain—Steel Drivers Mine A Deeper Vein of Lonesome

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

December 2008, Volume 43, Number 6

“It’s time for the uneasy listening portion of the evening, when bad things happen to good people.”

Mike Henderson grins under the brim of his black cowboy hat and hits a bluesy lick on his Gibson mandolin, surveying the packed-to-the-walls Station Inn. Nashville’s bluegrass nerve center and the SteelDrivers’ home base when they’re not on the road, an increasingly rare occurrence.

Henderson gets the expected laugh, but he’s not really kidding about the darkness to come. Murder, infidelity, war—this is not the feel-good commercial country that pays the bills in Music City. But, the SteelDrivers’ songs are the real deal, filled with the eternal truths of hard-core country and bluegrass.

For musicians living here, Nashville can be a very tough town. The musical gene pool is deep, club gigs are filled by top session players, and even they often have trouble drawing a crowd. Boasting the highest percentage of professional musicians of any American city, audiences here tend to be spoiled. But, after more than two years of playing the Station, their following has grown to where the folks handling the door for tonight’s show were turning people away by 7 p.m., two hours before the band hit the stage.

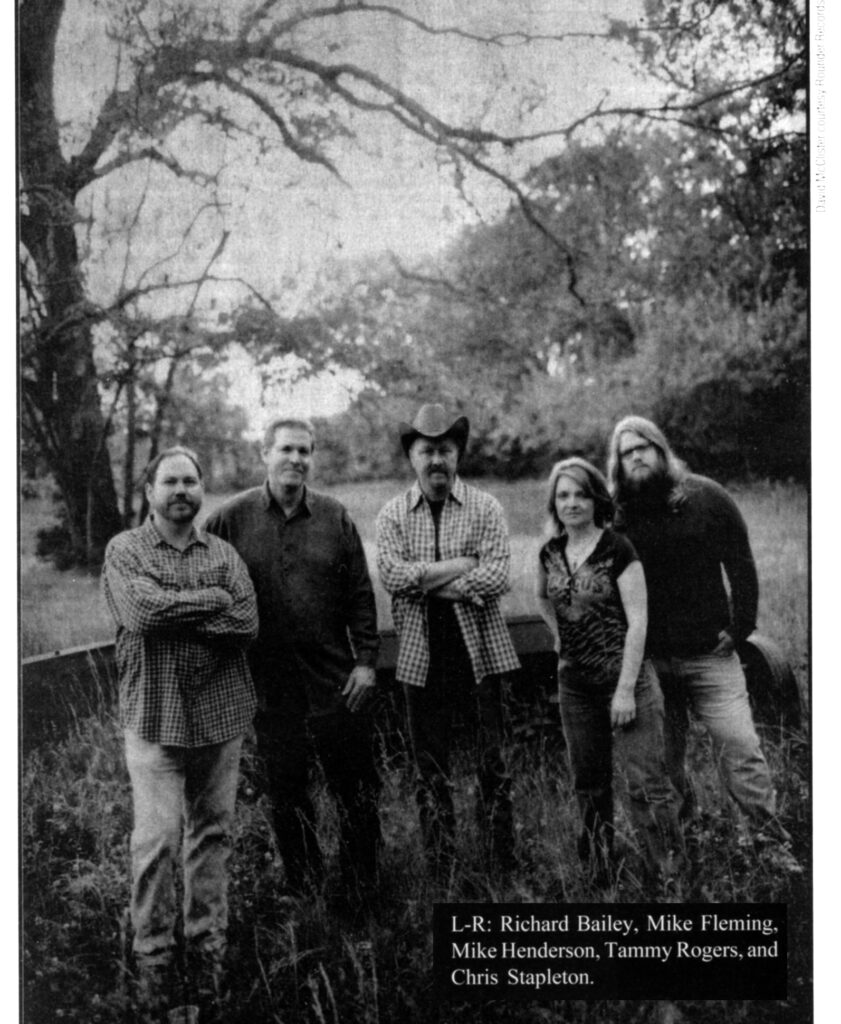

The SteelDrivers more than hold their own when it comes to session work. Henderson has written songs for the Dixie Chicks, Kenny Rogers, and the Fabulous Thunderbirds and has recorded with Emmylou Harris, Mark Knopfler, and Albert King and has several solo albums. Banjo player Richard Bailey has backed everyone from Bill Monroe to Johnny Cash to soul great Al Green. Fiddler Tammy Rogers is a first-call session player, her resume including long stints with Reba McEntire, Trisha Yearwood. and Patty Loveless. Bassist Mike Fleming has toured and recorded with Holly Dunn and David Olney.

As solid as the picking is, the band’s secret weapon is their material. The SteelDrivers feature only original songs—no covers, no classics—delivered by the powerfully soulful baritone of guitarist Chris Stapleton. It’s the songwriting team of Stapleton and mandolinist/slide guitarist Henderson that really sets the SteelDrivers apart from the bluegrass pack, commanding a fanatical following that quickly spread from fellow musicians to mainstream Nashville to the bluegrass world and beyond, as this band of Nashville veterans has emerged as one of today’s fastest- rising new groups.

Vince Gill has long been one of their most vocal fans. The Country Music Hall Of Famer and former Bluegrass Alliance member personally invited the SteelDrivers to open the show when he made a rare return to his roots at this past summer’s Ryman Auditorium bluegrass concert series.

“I’ve known all those pickers forever and they’re all great pickers, that’s a given,” says Gill. “But with Mike and Chris, they’re writing songs that are a cut above. And if you’ve got great songs, you’re light years ahead of the game.” Gill often jokes about his voice being higher than wife Amy Grant’s, but he’s an unabashed fan of Stapleton’s lower, lonesome sound. “To me, Chris Stapleton is a big reason they’re great. I think he conjures up a lot of memories of (former New Grass Revival lead singer John) Cowan. He’s really a fine soul singer and he doesn’t fit the mold of Monroe or Ralph Stanley.”

It’s a unique mix, a brand-new band of Music City survivors with a sound and a set-list completely their own. And they take it to the stage, making those songs come alive with a near-telepathic vocal and instrumental blend. “If It Hadn’t Been For Love,” a staple of their live shows that appears on both their self-produced first CD “Live From The Station Inn” as well as their self-titled Rounder debut, is a perfect example of everything they do so right. It opens with Stapleton’s understated vocal over muted guitar. Never would have hitchhiked to Birmingham, if it hadn’t been for love. The band kicks in after the first verse, and the song continues to build. What seemed like a typical love song morphs into an obsessive, homicidal love song, as Stapleton’s protagonist kills his unfaithful lover. Never would have loaded up a .44, put myself behind a jail house door, if it hadn’t been for love. Stapleton’s performance is an edgy, powerful portrait of pain, but the chorus kicks it up several notches, as the trio of Stapleton, Rogers, and Fleming weaves in and out of the single microphone with jaw-dropping, precise phrasing and dynamics. That’s the sound that convinced Rounder Records co-founder Ken Irwin to sign the SteelDrivers after attending their 2007 IBMA showcase.

Fiddler Blaine Sprouse, who’d played with Bailey in the 1990s in Nashville’s Cluster Pluckers, first contacted Irwin. Ken recalls, “I got an e-mail from Blaine, who had worked with us for quite a while, and it was totally out of the blue. It said, ‘I usually don’t get in touch with you about things like this, but I heard this group that just totally knocked me out.’” Irwin checked them out online and made a note to hear them at the upcoming IBMA World Of Bluegrass. “I went down there, and I was just not ready for it, even though I heard their music on their Website. Hearing them in person is just killer. There wasn’t just one song. With Dailey & Vincent (signed by Rounder around the same time), it was one song, ‘By The Mark.’ But, the SteelDrivers just had so many great songs. I was really surprised about some of the great material that didn’t make the first record. That was just astounding—material that most other groups would kill for—that didn’t make the record.”

That’s not too surprising, given that the SteelDrivers’ roots run even deeper in Nashville’s songwriting community than in its bluegrass scene. “It all comes down to the song” is a favorite saying in Nashville, and while the city is a capital of country, bluegrass, gospel, Americana, and even barbershop quartets, its largest, most diverse and dynamic music community remains its songwriters. And, due to the Nashville tradition of co-writing, it’s an incestuously close-knit community. Before they ever thought about forming a band, Mike Henderson and Chris Stapleton had been writing songs together for almost five years.

Bluegrass was a first love for Henderson, 55, originally from Independence. Mo., President Harry Truman’s hometown. He started playing bluegrass at 18, focusing on mandolin, supplemented with guitar and fiddle. “The sound of it just really killed me, just the way it all works, the way the instruments have to work together. I used to hang around a lot with old-time fiddlers and back them up. I was learning to play the fiddle at the time, and that whole kind of acoustic music culture appealed to me back then. I didn’t really like what rock-and-roll was doing.”

He scraped a living in a band with future SteelDrivers bassist Mike Fleming, who started on banjo. “We met when we were in college, and we kind of played our way through college and then kept on afterwards until about 1981,” says Henderson. “At that time, it was hard to make any money at all playing bluegrass. After I got tired of starving to death, I got into rock-and-roll and blues, which I’d grown up hearing around the house. Mom was a big fan of John Lee Hooker and B.B. King and that sort of stuff, so I had heard that since I was old enough to walk.”

Mike came to Nashville in the 1980s and made a name as a songwriter and guitar slinger, specializing in electric and acoustic slide. He was in the Dead Reckoning recording collective in the mid-1990s, helping define the Americana genre with drummer Harry Stinson (now with Marty Stuart’s Fabulous Superlatives), singer/songwriters Kieran Kane and Kevin Welch, and a red-hot fiddler named Tammy Rogers.

Rogers’ dad was a picker and she grew up playing bluegrass in the Dallas/Fort Worth area, often with banjo player Scott Vestal. She came to Nashville in Dusty Miller, a band of future all-stars featuring then-unknowns Tim Stafford (Blue Highway) on guitar, bassist Barry Bales (AKUS), and mandolinist (and her then- husband) Adam Steffey (currently with the Dan Tyminski Band). After a fine debut album, the band broke up, and Stafford, Bales, and Steffey formed the core of Alison Krauss’ Union Station. Rogers was hired by Patty Loveless, whose band also included bluegrass refugee Tim Hensley (now in Kenny Chesney’s band).

“I played with her for 14 months, starting in 1990 after Dusty Miller,” Rogers says. “Patty was the best kind of transition gig I could have hoped for. I’d never even thought about playing country. She was great to me, great to sing with. She was just great.” Leaving Loveless, she spent 15 months with Trisha Yearwood. By the end of that run. Nashville’s “Garth era” was in full sway, and the country boom meant plenty of TV and recording work. “There was a bunch of TV stuff in the mid-’90s. Between TNN and CMT. it seemed I was taping something about every week. I just kind of let the doors open and followed them and let things unfold. And I always missed playing bluegrass. but I knew I didn’t want to get back into it if it wasn’t really an exciting, challenging thing. And it wasn’t until this band got together, that it came back around for me.”

It was Henderson who first got everyone together in the summer of 2005. “I missed playing bluegrass,” he states. “It was kind of a combination of that and songwriting sessions with Chris. We’d been writing together for several years, and we had a lot of these songs just laying around. A few of them were getting cut— a lot of them weren’t. And I was thinking, ‘These are good songs, now.’ I was wanting to pick. I asked Chris if he was too, and he said. ‘Yes.’ I called everybody else and they said, ‘Yes.’ So, there we were.”

On banjo, Henderson recruited Richard Bailey. He’d grown up in Memphis, “Home of the Blues,” but when he discovered the soundtrack from Deliverance on the Bailey family turntable, the high school freshman switched from trumpet to banjo. In a few years, he was playing in the area’s premier bluegrass band, the Tennessee Gentlemen. On the festival circuit, he met a young fiddle prodigy, Tammy Rogers.

Relocating to Nashville in 1987, he played with such top artists as Curly Seckler, Roland White, Vassar Clements, and Larry Cordle and was profiled in the Tony Trischka/Pete Wemick book Masters Of The 5-String Banjo. In the early 1990s, playing with the Cluster Pluckers, Bailey came to the attention of the ultimate Nashville insider, Chet Atkins, who featured the Pluckers on a 1991 Austin City Limits appearance.

Henderson had all the pieces of the SteelDrivers puzzle. All that was left to do was fit them together. “Tammy and I were in the Dead Reckoners, and I knew Tammy and Richard had worked together years ago, so they knew each other. And Richard knew Mike Fleming a little bit.” Henderson explains. “So. I kind of knew everybody. Chris didn’t know anybody but me, and nobody else knew Chris. And that first time when we got together and he first started to sing, I looked around the room and I could see everybody kind of go. ‘Holy cow! Just listen to that!’”

“That was very exciting,” agrees Mike Fleming. “I was just blown away by his voice. I’m like, ‘Wow, this is great!’ And what was even greater was, after we tried a couple three traditional songs and then Henderson goes. ‘Hey, why don’t we try this one, Chris, that you and I wrote?’ And then it was like, ‘Hey now, this is really something.’”

All agree that Chris Stapleton turned a casual bluegrass jam into something much more. He was born and raised in the heart of the Bluegrass State, Johnson County in eastern Kentucky, but came to bluegrass music much later than the other SteelDrivers. He listened to Southern Rock until about ten years ago, when he was in his early twenties and Jesse Wells, a friend who taught old-time music at Morehead State University, introduced him to bluegrass. “I got into it pretty heavy, as far as listening goes and attempting to play some.” Stapleton explains.

In 2001, he moved to Nashville to become a songwriter and joined the staff of SeaGayle Music. He put performing on the backburner. “I’d play the Bluebird a little bit,” he says, citing Nashville’s legendary songwriter showcase. “I mainly just put my head down and tried to write as much as I could. It was always a goal of mine to be established as a writer beforehand, before I ever tried to make any leap toward doing it as an artist.”

For the next four years, he honed his craft and built his bank account, getting dozens of his songs recorded by the likes of Brad Paisley, Tim McGraw, Brooks & Dunn, and Patty Loveless, including number ones for Josh Turner (“Your Man”) and Kenny Chesney (“Never Wanted Nothing More”).

For those four years, Stapleton’s primary audience was his co-writers, and he made fans of them all. “I was writing with Tim O’Brien one day, and he said, ‘Hey, I’m playing at the Station Inn. Why don’t you come play guitar?’ And I was immediately freaked out. I hadn’t played onstage with anybody, let alone anybody of his caliber. He gave me a CD of songs he wanted me to learn. I hadn’t played bluegrass in a long time, at least since I’d been in town, and you got to keep up with it. So, I sat at home for two days just freaking. And Tim might not recollect the call, but I called him and said, ‘Man, I don’t think I can do it.’ He said, ‘O.K., you want to come and sing some anyway?’ And I said. ‘O.K.’ So my first trip to the Station Inn was with Tim. And I’m kinda glad I backed out ‘cause that night, it was Tim and Sam Bush and Dennis Crouch. It was a serious band that I probably, really was not in shape to hop up with at all. And I’m still not,” he finishes with a laugh. There was a lot less pressure when Henderson, his long-time writing partner, approached him about starting informal Sunday night sessions.

‘This band almost happened out of accident,” Stapleton explains. “Mike wanted to get together once a week and play some bluegrass. It sounded like fun.” But, with dozens of Stapleton-Henderson songs, the tight vocal trio, and Stapleton’s big, bluesy surprise of a voice, things escalated quickly from living room jams to VFW gigs to regular shows at the Station Inn. “Before we knew it, we had a set-list of all original music and we had a band and we had a record,” says Stapleton.

They got their name, says Stapleton, from a dream Henderson had. “Mike just walked in one night. He goes, ‘I’ve got a name for us, the SteelDrivers.’ And we all said, ‘O.K.’”

“Initially, the thought was just that we’d get together and play,” says Henderson. “We fully intended to do covers and traditional stuff and all that. And as we started to rehearse, Chris was pulling out songs that he and I had written, things that I hadn’t even considered would work this way. He has a real good way of getting inside a song and being able to put different spins on it. And, after a pretty short while, it became clear to us that we didn’t need to do any covers. So, then it became, ‘Then let’s not do any. Let’s just do stuff that we write.’ I don’t know if you call that a gimmick or a trademark or what, but that’s kind of where we are right now.”

Stapleton’s voice, the bandmembers’ varied experiences, and an exclusive reliance on original material creates a unique sound. Unlike many bluegrass bands, any change in personnel would drastically affect the SteelDrivers’ sound. Theirs is the bluest shade of bluegrass, as if Bill Monroe had gone to Memphis instead of Nashville and enlisted Gregg Allman as his lead singer. Bailey adds plenty of bluesy string bends, alternating with Henderson’s Monroe-style mandolin and non-traditional (for bluegrass, anyway) steel-bodied resonator slide guitar. Rogers is the brightest instrumental star of the SteelDrivers, tearing into fiddle solos with a lifetime’s experience and a beginner’s excitement. “Tammy kills,” Henderson states.

Blues and bluegrass are both musics for grownups, for people who’ve lived enough to experience pain and regret, yearning for the “old home place” or that “little girl of mine in Tennessee.” That sense of loss rings true in SteelDrivers’ songs like “Blue Side Of The Mountain,” “Drinkin’ Dark Whiskey,” and “Midnight Tears.” Those genuinely adult themes are what separates the SteelDrivers from much of bluegrass’ freshman class, who many times let instrumental virtuosity get in the way. playing bluegrass like it’s an Olympic event—higher, faster, stronger.

Their unusual approach has earned the SteelDrivers their share of accolades, winning IBMA nominations for Album and Song Of The Year (“Drinkin’ Dark Whiskey”) as well as Emerging Artist Of The Year. They were also nominated for Emerging Artist in 2008’s Americana Music Awards.

Their unique sound brought the SteelDrivers to late-night TV with a July appearance on the Late Night With Conan O Brien show. They shared the show with Senator John McCain, and the added security made it even more surreal than your usual national network debut. “There were Secret Service guys all over and bomb-sniffing dogs,” Henderson says, adding that the band took it in stride. “It was fun, and they treated us real good. They also complimented us when it was all over on us being so easy to work with.”

It’s been a heady, fast-paced rise, but as they ready their second Rounder CD due out in March 2009, pouring through dozens more Stapleton-Henderson songs, it’s still the music that drives the SteelDrivers. “‘It’s new, but it sounds old,’ is what some people have said,” says Fleming. “And I agree with that. We love bluegrass, but we’ve had to do something else to make a living. We’re bringing a little of that to the table with us. For me, it might be the bass pattern. It’s like Tammy said, ‘Chris and Mike don’t write songs to be bluegrass songs, they just write songs.’ And we don’t arrange songs to be bluegrass songs; we just arrange them to however they feel best on these traditional instruments. If it’s a 2/4 bluegrass beat, so be it. But. if it turns out to be a waltz or in a blues tempo, wherever it feels comfortable and feels right, that’s where it’s gonna land. We’re not going to force it into a certain category or into a certain feel.”

“That’s the thing about this band,” admits Rogers. “If it was just straight bluegrass. I’d probably get bored. But, after doing so many different styles and different types of things, in this band, it’s just great music.”

Larry Nager is a Nashville-based musician, journalist, and documentary film maker. His 1993 film, Bill Monroe: Father Of Bluegrass Music has recently been reissued on DVD.