Home > Articles > The Archives > The Making of Rounder 0044

The Making of Rounder 0044

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

September 2015, Volume 50, Number 3

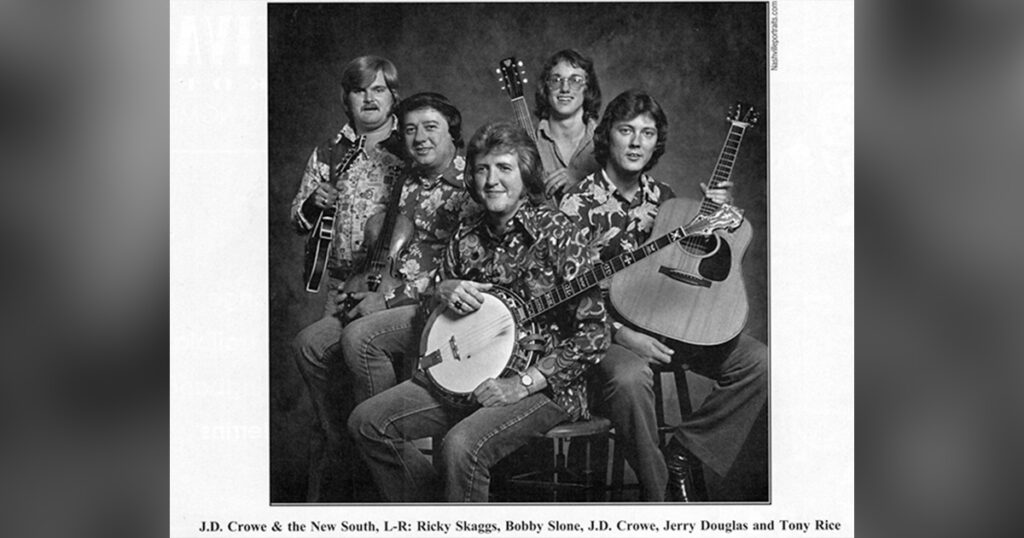

Four decades ago, J.D. Crowe & the New South went into the studio to record one of bluegrass music’s most influential albums. The band consisted of J.D. Crowe, Ricky Skaggs, Jerry Douglas, Tony Rice, and Bobby Slone, and their 1975 eponymous album is commonly referred to by its stock number, Rounder 0044 or 0044. They changed the course of bluegrass and then, after a few months together and as their only album was being released, they were no more. Three of the five band members left to pursue other successful musical ventures. By seamlessly combining traditional and progressive ideas, J.D. Crowe & the New South and Rounder 0044 made a monumental impact on bluegrass music.

J.D. Crowe

The banjo did not originally intrigue J.D. Crowe. When J.D. was growing up in the ‘40s, the banjo was essentially a prop used in comedy and vaudeville routines. “That’s the way I associated the banjo, and I didn’t really care for it,” says J.D. On September 17, 1949, Crowe saw Flatt & Scruggs for the first time, and seeing them perform changed his life. Once he saw and heard Earl Scruggs play the banjo in his innovative three-finger-style, J.D.’s perception of the banjo was radically changed. “I had never heard an instrument played like that!” He asked his parents for a banjo and received one the following Christmas. He quickly became very proficient on the instrument.

As a teenager, J.D. was hired by Jimmy Martin. As a member of the Sunny Mountain Boys, he secured his place in bluegrass history. His powerful banjo helped define Jimmy’s signature sound. “When I went with Jimmy, I wanted to play like Earl. I guess everybody did,” he recalls. He quickly learned, however, that he couldn’t play just like Earl and play with Jimmy. “Jimmy had a different style, and you had to match that style to make it right. He did not want to sound like anyone else.” J.D. admits that he hadn’t been too sure about trying to not play exactly like Earl, but looking back, he knows Jimmy was right. “You can’t beat a man at his own game, because he’s already done it, and he done it the best there ever was,” he adds.

After leaving Jimmy in 1961, J.D. began playing locally in his hometown of Lexington. His banjo playing started to take on a new dimension: he began to play different licks and riffs on the instrument. Drawn to early rock-and-roll music he heard on the radio, Crowe decided to emulate different instrumental runs on his banjo, like he heard on electric guitar, piano, steel guitar, etc. This gave his banjo playing a very bluesy element, further defining his style. Combining the hard-driving sense of timing that he picked up from Jimmy Martin, the bluesy licks he learned from rock-and-roll, and his deep love for Earl Scruggs, J.D. Crowe became one of the premiere banjo players in bluegrass music.

Bobby Slone

J.D. began playing locally in Lexington at various nightclubs and bars, eventually forming J.D. Crowe & the Kentucky Mountain Boys. It was during this era that he first met Bobby Slone. Bobby had already been playing country and bluegrass music for several years, most notably in California with the Kentucky Colonels. He moved to the Lexington area in early 1964. This began a friendship and musical partnership that lasted from 1964 until 1988, when J.D. decided to take a hiatus from music. “He and I had a lot of fun playing together,” says Crowe. “He was like my right arm.”

Although Bobby was a member of Crowe’s band longer than anyone, he is often the most overlooked member. J.D. thinks that much of the lack of focus on Bobby is due to his primary choice of instrument. “A lot of people look at bass players as not important, but they’re wrong,” says J.D.

“We always tried to shed some light on him,” says Jerry Douglas, former member of the New South. “Whenever somebody would say something about one of us or all of us, we’d go, ‘Well, okay, check this guy out.’” Due to his left- handedness. Bobby’s bass playing was particularly impressive. “He always stood on the wrong side of it,” notes Josh Williams, three-time IBMA Guitar Player Of The Year. “He learned how to play right-handed instruments, so to watch him was unusual, but he always had it right there.”

Red Slipper Lounge

The Kentucky Mountain Boys played Lexington’s club scene for several years before landing one of the most unique gigs a bluegrass band has ever had. In 1968, the band began playing at the Red Slipper Lounge at Lexington’s Holiday Inn. “Back then, that was unheard of to have music like that in a place of that caliber,” J.D. remembers. “The first night we were there, it was packed. You couldn’t get them in.” The hotel signed the band to a year-long contract, requiring them to play five nights a week, four shows a night, eight months a year: an astonishing rate of 640 shows a year.

Playing twenty shows a week, the band needed to learn new material. The need was two-fold. For one, playing mostly to the same fans every week, the band had to have an abundance of songs to keep things fresh for themselves and the audience. Also, the crowds at the Holiday Inn were not typical bluegrass fans. “We had a lot of people college age, then we’d have business men that would stay there at the Holiday Inn,” remembers former New South member, Ricky Skaggs. To hold the interest of this diverse crowd, the band performed material that was equally diverse. “We had to learn some new stuff. A little different, but we’d work it out,” Crowe adds.

Aiding in diversifying the material was a young mandolin player named Larry Rice, who left California and joined the group in 1969. Larry introduced J.D. to many alternative country records, such as the Flying Burrito Brothers, which were popular in California at the time, and the band began playing such non-bluegrass tunes as “Sin City,” “Devil In Disguise,” and “God’s Own Singer.” J.D.’s love for old rock-and-roll music was represented in their repertoire as well, through songs such as Fats Domino’s “I’m Walkin’” and Roy Hamilton’s “You Can Have Her.”

Tony Rice

Shortly before changing the band’s name and sound in 1971, J.D. hired Larry’s brother, Tony, to play guitar. Tony and his guitar playing would be a key factor in not only the development of the New South, but also in the future of bluegrass. Tony was highly influenced by West Coast guitarist Clarence White. Clarence was one of the first bluegrass guitarists to take extensive lead solos; however, being based on the West Coast, bluegrass as a whole had not been widely introduced to his innovative style. Tony brought the idea of bluegrass lead guitar from the West Coast to the more bluegrass-friendly East and quickly gained notoriety.

According to J.D., Tony soon surpassed even Clarence’s ability, taking bluegrass guitar to another level. “His lead guitar was different, and that was good,” says Crowe. Not only did Tony’s playing add a third lead instrument to the group, but it helped differentiate this band from all others. Although he was blown away by Tony’s lead guitar picking, J.D. felt that Tony’s rhythm playing could use some work. Crowe was accustomed to a more aggressive Jimmy Martin-esque style of rhythm. “Well, I knew he could do it,” he says. “He could hear that he needed to change, and he did that.” Tony quickly developed a style of rhythm playing that suited J.D.’s needs.

“Mostly, Tony learned how to play with J.D. and react in syncopation,” says Tim Stafford, acclaimed guitarist and author of Still Inside: The Tony Rice Story “He built a rhythm guitar style that is still being copied and is still very, very influential in modem bluegrass.” The Jimmy Martin influence on Tony’s rhythm, which J.D. instilled in Tony, allowed Tony’s guitar playing to, rhythmically, have a very traditional feel, while still allowing room to expand the instrument’s limitations. This provided a balance of tradition and innovation, which matched Crowe’s balanced banjo style.

Tony’s voice would also prove to be one of the most influential in bluegrass. Skaggs noticed that Tony’s vocal style was different from the start: “His rhythm of singing and his approach to singing was very unique. He didn’t sound like any of those guys in bluegrass.” A Californian, Tony had a more urban-sounding voice when compared to traditional bluegrass vocalists, who primarily came from rural backgrounds. Vocally, he was drawn to singer-songwriter oriented material. He loved singing songs from Gordon Lightfoot, Bob Dylan, and Ian Tyson, as much as he enjoyed singing songs from Flatt & Scruggs and Jimmy Martin. Ricky continues, “He had such a voice that lent itself to singing a non-traditional sounding song.” This broadened the band’s repertoire even further to include folk and singer-songwriter songs alongside alt-country, rock-and-roll, and bluegrass favorites.

Bluegrass Evolution

In 1971, J.D. Crowe & The Kentucky Mountain Boys changed their name to J.D. Crowe & The New South, coinciding with a change in direction. Feeling that the name “Kentucky Mountain Boys” labeled the band as strictly bluegrass, J.D. chose the name “New South” as a way to make the band’s music more widely accessible. Moving from a more tradition-oriented bluegrass sound to a “country-grass” feel, this new sound, complete with electric bass, drums, piano, and a pedal steel guitar, went over well in the band’s home base of Lexington.

In 1973, the band even recorded an album with this new sound, entitled Bluegrass Evolution. It was the complete opposite of the Kentucky Mountain Boys’ traditional sound. “It had drums on every cut,” notes Josh Williams, “some of them even half-time, rock-and-roll sounding.” The New South, at this time, was as progressive as the Kentucky Mountain Boys had been traditional. Although recorded in 1973, Bluegrass Evolution lay unreleased until 1977. The album would have been J.D.’s first since 1971, and the first under the New South. The contract with the record label was for two years, meaning the band could not record a new album until 1975, four years after the last Kentucky Mountain Boys album. This delay made the bluegrass world very anxious for a new J.D. Crowe album.

Rounder Records

In August of 1974, the three founders of Rounder Records (Ken Irwin, Marian Leighton, and Bill Nowlin) attended the eighth annual Gettysburg Bluegrass Music Festival. The festival included a rare non-Lexington area appearance of J.D. Crowe & The New South. At Gettysburg, Rounder approached J.D. about recording an instrumental banjo album for their new label. “We thought it was a great idea,” recalls Ken Irwin. Rounder was just getting started, and their roster had little to no artists with a national following. By approaching J.D. with the idea of a solo album, “We thought we’d have a much better chance,” says Ken. However, the idea did not appeal to J.D. He politely declined Rounder’s original offer. “About two hours later, J.D. and Hugh Sturgill, who was referred to as J.D.’s manager at the time, came over to our record table where we were set up and said they’d like to speak to us,” remembers Irwin. The conversation floored the Rounder team. “They said before that they weren’t interested in the banjo record, but would we be interested in doing a band record.” To a small independent record label, the idea of having J.D. Crowe & The New South work with them was monumental. “It was a combination of a bluegrass veteran, but also arguably one of the hottest, if not the hottest young band out there,” says Ken.

Rounder appealed to Crowe for several reasons, but being a new label was particularly attractive. “I knew we were their first [bluegrass band],” says J.D. “We were kind of one of the first, as far as professional groups, to be going with them.” This meant that they would be the only bluegrass band receiving all of the label’s attention. After discussing it, J.D. decided that Rounder would be a good fit. Due to their previous contract, they would not be able to go into the studio until January. This delay would be very fortunate, as the timing allowed for one more major change to take place.

Ricky Skaggs

In the fall of 1974, Larry Rice announced that he would be leaving the New South. His departure left a vacancy for a mandolin player and vocalist. Tony Rice suggested Ricky Skaggs, who was currently playing fiddle in the D.C. area with the Country Gentlemen. Ricky was primarily known for being a fiddle player at this time, but he would quickly prove that he was equally proficient on mandolin. His biggest influences on mandolin included bluegrass legends Bill Monroe, Peewee Lambert, and Bobby Osborne. This is not where his mandolin playing stopped though. Some of Ricky’s favorite music at this time was the jazz fiddle and guitar stylings of Stephane Grappelli and Django Reinhardt. “I think I started in my mind thinking how I could play these licks that I knew from Django and Stephane,” says Ricky. “How can I play some of these licks and kind of incorporate them into bluegrass in a way that kept the integrity of the music?”

“Nobody played like him. He had this jazzy, mandolin style that I think was highly influential in what’s happened [since],” says Tim Stafford. “It was just great and aggressive,” Alison Krauss says about Ricky’s playing. “His [fiddle] playing and his mandolin playing and his singing—there was so much attitude.”

Coinciding with Ricky’s entrance into the band, J.D. decided it was time to go back to being all-acoustic. Returning to an acoustic sound, while maintaining the diverse material and modern sensibilities, brought this edition of the New South somewhere between the sound of the Kentucky Mountain Boys and the Bluegrass Evolution era. It was bringing in Ricky on tenor, however, that helped take this band over the top. Before this, Tony was forced to sing mostly tenor and high lead, because no one else could reach the notes. By adding Ricky, a natural tenor singer, Tony was free to sing a more comfortable lead, allowing his voice to truly shine on lead vocals. This also allowed J.D. to drop down to his natural baritone part, instead of lead or high baritone in the trio.

Ricky also provided the New South with a second lead vocalist, a rare commodity at this time. “I never got to sing lead before,” says Ricky, who was excited for the opportunity. This change, along with Ricky taking over the emcee duties, provided Tony with some much needed vocal rest, necessary if one is performing twenty shows a week. The juxtaposition of Ricky’s powerful, more traditional sounding voice against Tony’s smooth, progressive sounding voice created a unique blend that maintained this band’s blend of tradition and innovation. The New South’s singing made progressive songs sound more traditional and traditional songs sound more progressive, and became just as unique and diverse as their range of material.

Jerry Douglas

After rehearsals were underway for the upcoming album, Ricky began thinking about his pal Jerry Douglas, a young Ohio dobro player with whom Ricky had worked during his time with the Country Gentlemen. When the band was practicing material, particularly some of the Gordon Lightfoot songs which Tony brought to the group, Ricky thought that some would sound great with a dobro. “I mentioned it to J.D., and I think he was a little hesitant at first,” remembers Ricky. However, having heard how talented Jerry was on the road with The Gents, and after the persistence of Ricky and Tony, J.D. agreed to allow Jerry to play dobro on the record, under the expectation that he would only be featured on a few songs. Jerry fit the band’s sound so well, that those two or three songs would blossom into eight of the eleven songs on the record.

At a time when few bands featured a dobro, having the best young dobro player in the country appear on the majority of the album, further helped separate this band as something unique. Michael Stockton, who plays the dobro for Flatt Lonesome (IBMA’s 2014 Emerging Artists Of The Year), points to Jerry’s involvement on this record as particularly noteworthy. “After learning how young Jerry Douglas was when he recorded on that album, it’s so inspiring to me as a person just to know that he was kind of taking the dobro into new territory.”

Jerry’s playing style was squarely planted between the rousing sounds of Josh Graves and the contemporary stylings of Mike Auldridge. Rob lckes, who has been IBMA’s Dobro Player Of The Year an astounding 15 times, notes why Jerry’s playing was so unique. “He had the cleanliness of Mike Auldridge’s playing and technique, but he also had the blues and that energy that Josh Graves brought to it. It was just a perfect mixture of those two guys and, of course, everything that he brought himself and created himself.” Jerry’s reverence for both Mike and Josh, who were completely different stylistically, along with a willingness to experiment on his own, further established the band’s ability to combine traditional and progressive bluegrass in a way that satisfied both audiences.

The Songs

On January 16th, 1975, J.D. Crowe & the New South met at Track Studios in Silver Springs, Md., to record their new record, exactly one day after the expiration of their previous two-year contract. The majority of the songs on the album were from the band’s Holiday Inn repertoire. As mentioned previously, the diverse crowd for whom the band played on a nightly basis at the Holiday Inn resulted in an equally diverse well of material. “We just kept feeding the audience just enough of the new stuff to keep their interest up and keep them hungry enough that they could still get satisfied with the traditional stuff,” remembers Ricky. “I think that’s the reason we were able to do some of these songs and get away with it, because we had just proven that it works. The audience proved it back to us.”

The band was careful to maintain a balance of old and new songs in their performances, and this balance was applied to the album as well. The eleven songs that made it onto the album came from a variety of sources. The following list features the album’s final song selections. (Flatt & Scruggs’ “Why Don’t You Tell Me So” and an alternate version of “Cryin’ Holy” featuring Emmylou Harris were recorded, but never released.) Songs with a more progressive origin are in italics.

“Old Home Place”

“Some Old Day”

“Rock, Salt & Nails ”

“Sally Goodin”

“Ten Degrees (And Getting Colder) ”

“Nashville Blues”

“You Are What I Am ”

“Summer Wages”

“I’m Walkin’”

“Home Sweet Home Revisited”

“Cryin’ Holy”

One may notice that “Rock, Salt & Nails” is in italics. That is due to different perceptions as to whether the song should be considered of traditional or progressive origins. While the band learned the song from Flatt & Scruggs, Flatt & Scruggs learned the song from a non-traditional source. Excluding “Rock, Salt & Nails,” the album’s track listing features exactly half traditional songs and half progressive songs.

Even within their respective categories, the songs come from a range of sources. “Old Home Place” comes from The Dillards. Both “Some Old Day” and “Nashville Blues” are vintage Flatt & Scruggs. “Sally Goodin” is one of Appalachia’s oldest instrumentals, while “Cryin’ Holy” is a gospel standard.

The progressive songs come from even more diverse backgrounds. Both “Ten Degrees” and “You Are What I Am” come from the pen of Canadian singer/ songwriter Gordon Lightfoot. “Summer Wages” comes from Ian Tyson, another Canadian. “Home Sweet Home Revisited” was written by Rodney Crowell, but the New South learned the song from country superstar Jerry Reed. The most popular Fats Domino bluegrass song “I’m Walkin’” is one of the most eyebrow-raising songs on the album, but the New South made it work, just like they did with nearly every song they interpreted.

Summer of 1975

The album would not be released until late summer, but word was quickly spreading about this fresh new sound that J.D. Crowe & the New South was making. Jerry Douglas joined the band full-time in June of 1975, just in time for the busy bluegrass festival season.

“By the time we got to Berryville [Va.] that summer, we were the undisputed Kings of Bluegrass,” Jerry recalls. “We were playing, and every band that was there was standing around the stage watching it. We knew at that point that we were making something special.” It was at Berryville that the band began to realize that they were making history.

After a whirlwind summer festival season, the band ended August with a ten- day/eight-show tour of Japan. Enjoyed as everyone’s first trip to Japan, the tour was quite an experience. “We were playing to twenty-five hundred people every show— and running to the car and them trying to tear your shirt off,” says Jerry. “It was like Beatlemania or something!” J.D. remembers one particularly exciting show when the band was rushed following their performance, and cops had to pull screaming fans from the hood of the band’s limousine. “Now, I know how Elvis felt,” J.D. says with a smile.

The trip to Japan was bittersweet. It would turn out to be the last shows performed by this lineup of the New South. Tony Rice told J.D. that he would be moving back to California to make new music with David Grisman. Not knowing if he would have the same vocal chemistry that he had with Tony, Ricky Skaggs decided to take this opportunity to form his own band, which he did with Jerry Douglas. One of the greatest bands in bluegrass history lasted only ten months, but at least their only album was finally released after returning from Japan.

The Impact of Rounder 0044

By Daniel Mullins

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

September 2015, Volume 50, Number 3

Forty years ago, J.D. Crowe & the New South recorded one of the most influential bluegrass albums of all time. In 1975, J.D.’s band, the New South, had one of—if not the—most talented band lineups in the history of bluegrass music. J.D. Crowe (banjo), Ricky Skaggs (mandolin and fiddle), Jerry Douglas (dobro), Tony Rice (guitar), and Bobby Slone (bass) created one of the most significant albums in bluegrass history. A classic bluegrass album, J.D. Crowe & The New South has been so popular among bluegrass fans that it’s most commonly referred to by its stock number: Rounder 0044 or simply 0044. Through their seamless combination of traditional and progressive ideas. Rounder 0044’s impact on bluegrass music is still being felt today.

Overall, the immediate impact of the self-titled album was positive. For certain, all bluegrass fans were talking about it. Most people loved it, especially fellow pickers. However, some folks felt that the record was too modem by including Fats Domino and Gordon Lightfoot songs on a bluegrass record. “Them kind of people didn’t count to me,’’ says J.D. “They didn’t know the difference.”

The original review of the album for Bluegrass Unlimited was particularly underwhelming. While applauding the instrumental virtuosity of the performers, the reviewer did not approve of the choice of material. He felt that the band should have stuck to more traditional songs. “The point he missed was that those have already been done thousands of times,” notes bluegrass historian Frank Godbey. “To my ears, they were taking material from a variety of sources and applying good, solid bluegrass lead to it.” Frank points out that, while other bands such as the Country Gentlemen and the Seldom Scene were also taking material from outside bluegrass, what made the New South’s choices so unique was the way they made the material fit them. “I think that’s a large part of the appeal; it was such a solid bluegrass foundation.”

“I didn’t know the first time I heard these songs that they were Gordon Lightfoot tunes or whatever,” says Balsam Range’s Tim Surrett. “They just did it, and it sounded like them. It didn’t sound like them playing a Fats Domino song. It was their song. It was not a ‘covered’ sounding song.”

The band managed to make bluegrass “cool” by recording material from outside of the genre. “[J.D.] got material from many sources, which proved that music is just music,” says Don Rigsby. The album’s material and fresh arrangements particularly appealed to younger fans. “It was like a leap further than what the Country Gentlemen did when they brought some non-traditional songs into the music,” adds John Lawless.

While the New South were not the first to record non-bluegrass material, it can be argued that they pulled off these new songs in a way that was unique among their peers. “It set a standard of execution and performance of ideas that weren’t drawn from the original founders of bluegrass,” says award-winning banjo player, Kristin Scott Benson, a member of The Grascals. “When it comes to the execution and slickness, this band achieved a new level of greatness when it came to just being so accurate and clean and polished-sounding.” The band’s level of proficiency in both picking and singing, when combined with the band’s fresh ideas, created a combination which seemed to connect with broader audiences including the younger generation.

The band’s youth caught the attention of the young crowd as well. These were not old men playing “hillbilly” music in overalls or stuffy suits. Lawless, who was a young person when 0044 was released, can remember the band’s youth being particularly appealing. “I could look and see this wasn’t just old mountain hillbillies who played this music,” he recalls. “These were young people with psychedelic shirts and blow-dried hair making exciting music for fans of all ages. This is what it must be like for somebody who’s in their late teens/early twenties now when they might go see Mountain Faith or Flatt Lonesome—somebody their age.”

Dr. David Haney, professor of Appalachian Studies at Emory & Henry College, points out. “This was such a hip album that people who had kind of denigrated hardcore traditional bluegrass and were looking to the newgrass all of a sudden heard this and were like, ‘Wow! Who are these people?’” The excitement about bluegrass which 0044 generated among young bluegrass fans was unique for a genre which maintained a predominantly older audience, a trend which still holds true.

The fresh perspective and careful approach brought about by 0044 is pointed to by most as the beginning of the modem era in bluegrass music. “It brought some new material and new ideas about what could be mainstream bluegrass material, not fringe, not urban—no kind of qualifiers—but heartland bluegrass,” says Jon Weisberger, bluegrass journalist and current chair of the IBMA board of directors. He also adds. “It was reasserting a kind of rhythm and timing and precision in the vocals that were shaped by earlier generations of bluegrass, that were direct linear descendants of Jimmy Martin and Flatt & Scruggs, and sort of legitimized those things in the mainstream bluegrass: the world of Bluegrass Unlimited and the festival scene.”

John Driskell Hopkins of the popular country group the Zac Brown Band adds, “These incredibly talented young men redefined what Bill [Monroe] started and Lester [Flatt] and Earl [Scruggs] made legend. In doing so. they paved the way for the future of the music and for what is today’s roots, folk, and Americana genres.”

As the first generation of bluegrass pioneers had already been established, the opportunity was ripe for someone to carry the music on to the next generation of fans. “Here’s Crowe who has connections to Jimmy Martin & the Sunny Mountain Boys and helped to create that classic sound. But. [J.D. and the New South] are young. They present themselves young and hip. They’re playing something that is clearly not 1950s bluegrass, but equally clearly has the musical values that are the center of bluegrass.” The band’s harmonies, timing, and precision marked this band as bluegrass, even if their choices in material were not always of the bluegrass persuasion. “It’s a powerful package,” says Jon. “They said, ‘Here’s a direction that folks who want to stay in the bluegrass world and really be part of the core of bluegrass can follow that isn’t backward looking, but also isn’t going off in different directions. It really is a new generation of this kind of stuff: progressive in a traditional way.’” The album created an entirely new way of thinking to bluegrass, creating endless opportunities for the genre to grow and flourish, while still maintaining the essence of the genre’s founders.

0044 quickly began to take on iconic status, largely due to the fact that the band lineup no longer existed. “Because the band lasted such a short time, that record was the only commercially available artifact of that band,” notes bluegrass historian Fred Bartenstein. “In some interesting ways, John F. Kennedy is a famous president. Because he died young, he was legendary. That particular band of the New South became legendary because they didn’t exist anymore.”

The legendary status of the band and the album only grew as each of the individual members went on to achieve great success in various fields of the music industry. Tony Rice took acoustic guitar to new heights, not only in bluegrass, but in jazz as well. Jerry Douglas quickly became, arguably, the most famous dobro player in the world. He has since recorded with dozens of artists, including Paul Simon and Mumford & Sons and currently tours as a member of Alison Krauss & Union Station. Ricky Skaggs eventually joined Emmylou Harris’ Hot Band, but rose to country superstardom in the ’80s, racking up 12 number one hits, notably “Highway 40 Blues,” “Country Boy,” and “Honey (Open That Door)” and also won multiple Grammys and CMA Awards. J.D. Crowe and Bobby Slone continued with the New South and helped develop many other great talents in bluegrass and country music, including the great Keith Whitley.

Acclaimed country artist Lee Ann Womack was introduced to the New South after having first listened to some of the band’s members apart from the legend of 0044. “I came to J.D. Crowe & the New South after falling in love with Skaggs and Rice,” she says. “So I was probably looking for more from both of these guys and wasn’t disappointed.” She feels that the later success of the individuals on this album was a key factor in its continued popularity decades later. “How could it not?” she asks. Using Jerry Douglas as an example, she says, “If you’re a fan of Jerry Douglas, and I am, you’re eventually going to go back and back and research all you can find.” With J.D. Crowe, Tony Rice, and Douglas’ names all becoming synonymous with their respective instruments and Ricky Skaggs becoming one of the most successful bluegrass stars in the genre’s history, the band’s status as a bluegrass super-group is without dispute.

As each of the members of this band achieved more success individually, it further added to the allure and mystery of this album. “It became an underground sensation. ‘Have you heard about this fabulous, sensational band? That band that only lasted a short time? A supernova,’” says Fred Bartenstein.

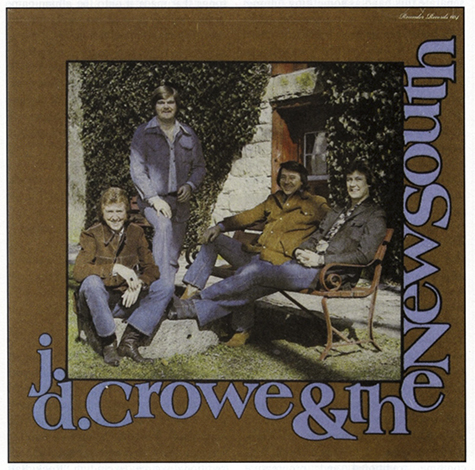

The fact that the album seemingly did not have a title added to the record’s legendary status. As the band and the album shared the same name, people had to come up with ways to distinguish between the two. Many folks began referring to it as “The Old Home Place Album” due to the album’s opening song which became the band’s signature song for the next four decades. Some simply called it “The Brown Album” because the predominant color on the record jacket was brown. However, the most enduring name for the album simply became the album’s stock number. Once the phrase 0044 caught on, the cult status of the album was solidified. Nearly all bluegrass fans refer to the album as 0044, further adding to the legend and mystery surrounding the record.

After its original release, there was a controversy over the original cover. On the initial cover, J.D. Crowe’s middle finger is extended, creating a gesture which many found obscene. While many folks never noticed the gesture, several consumers expressed their discontent to Rounder Records. This caused the label to redo the cover art after the initial printing. While the controversy may have embarrassed the young label, the mystery further aided in its legendary status (and made the album even cooler among young folks).

The success of 0044 was so great that when J.D. Crowe returned to bluegrass music after a hiatus in the late ’80s, he concocted a band that was determined to record new music in the exact same style of the famous 1975 band. And just last year, an all-star J.D. Crowe tribute band formed with the sole purpose of keeping the music of the New South alive, now that J.D. Crowe has retired from touring fulltime.

The generation of bluegrass players who grew up listening to this album as kids is how the band and album’s impact is still most visible. “Just like how J.D. Crowe’s generation learned every note that Earl Scruggs played on the Foggy Mountain Banjo album, I think there was a generation that grew up learning every note on Rounder 0044,” says Fred. That generation are now bluegrass veterans and most all point to that album as influence on their musical life. “For several years after that album was released, all banjo players tried to play exactly like Crowe did on that record,” says Aaron McDaris, banjo player for the award-winning Rhonda Vincent & The Rage. “I’ve listened to their record so much that it’s almost ridiculous!” says Tim Stafford of Blue Highway. “It’s one of the albums I can go back and listen to, and it continually gets me excited about why I love bluegrass.”

This generation’s enthusiasm for 0044 resulted in some unintended negative consequences in bluegrass as a whole, by no fault of J.D. Crowe & the New South. The love of this record permeated an entire generation of bluegrass pickers that so many young musicians wanted to play just like Tony Rice on guitar or just like J.D. on the banjo, or they wanted their band to sound just like the 1975 edition of the band. While this passion is a true testament to its impact on bluegrass, those who essentially imitated or mimicked the New South sound helped create, according to some, a homogenization of bluegrass styles. “There are so many people trying to imitate that sort of cool sound (and we’re still seeing this in a lot of bands) that there’s a loss of that kind of hardcore timing and the diversity,” says Dr. David Haney. “If you listen to the early bands— the Osborne Brothers, Bill Monroe, The Stanleys, Jimmy Martin, Reno & Smiley, Jim & Jesse—they all had completely different sounds and different senses of timing. They were consciously trying to identify themselves as a different thing. Now, there’s this sort of generic bluegrass sound that, for many bands, is more homogenous than it was really in the ’50s, and I think that’s partly because of the huge influence of that record.”

With so many musicians trying to play exactly the same way, many claim that 0044’s popularity unintentionally aided to the lack of diversity in bluegrass, stylistically. “Nobody else sounded like 0044, but people after that just kind of watered down [the genre],” Haney adds. While 0044 may have indirectly had some negative consequences on bluegrass, its positive contributions to bluegrass make it one of the most important albums in the genre’s history, solidifying its legacy as an all-time classic.

Among artists, there has been no larger supporter of this album’s legacy than Alison Krauss, the most Grammy-award winning singer of all time. Arguably the most well-known bluegrass artist in history (with Flatt & Scruggs coming in a close second), Alison Krauss points to 0044 as her biggest inspiration as to why she makes music. “It influenced every bit of music I ever made, because it was what made me really want to play,” she says. “It’s what had the love attached to it. It’s what made me want to be better and made me wanna learn and investigate. It was the beginning of me loving music.”

Forty years later, Alison sees this album having the exact same impact on bluegrass that it did in 1975. “Everybody’s had the same reaction to that, so there’s nothing that gets played that doesn’t have that attached to it. There’s nothing that’s happening that doesn’t have that in the very essence of what somebody’s playing these days. You can’t suddenly take that out or say this record isn’t involved in that particular song over here, because it is. There’s no way to extract it from somebody growing up.”

By having such a generation-to- generation impact, the album and its legacy have lived on like few other records have. “Every generation discovers it as they discover it from their parents, and their parents show it to them,” says Skaggs. “It’s just been one of those that’s been tried and true.”

“It was a landmark,” says Jerry Douglas. “It was a good time to set up some mileposts for other people too. I don’t think we were thinking about it in those terms at all, but it did happen.” Dominic Illingworth, bass player for Flatt Lonesome, adds, “It can affect so many different people in bluegrass, in so many different ways—no matter what your age is, if you grew up in the music, if you’re new to it—it has a place for everybody. People younger than me can look back to that forty years from now, listen to that, and that could still be something to encourage them as they’re a new musician, a new singer, or just getting into bluegrass.”

“I don’t think that anyone will ever make a record that’s better than that record. There might be someone coming along—it hasn’t happened yet—but there might be someone that’ll come along and make one as good, but it hasn’t happened yet,” says Don Rigsby, former member of the New South. “That record has a life to it. It’s real honest-to-God music, and it has life to it. That’s the legacy—that it’ll live on forever because the music is alive on that record.”

“That had the feel,” says J.D. “It’s just something magic about that, that you can feel.” By combining elements from traditional and progressive bluegrass, J.D. Crowe & the New South created a sound and a record that completely changed bluegrass music, and the bluegrass community still feels the impact of that band and that album forty years later.

Daniel Mullins is host o/Bending The Strings on the Classic Country Radio network. He’s currently finishing a degree in American Studies at Cedarville University’ in Ohio.