Home > Articles > The Archives > The Stability and Versatility of The Seldom Scene

The Stability and Versatility of The Seldom Scene

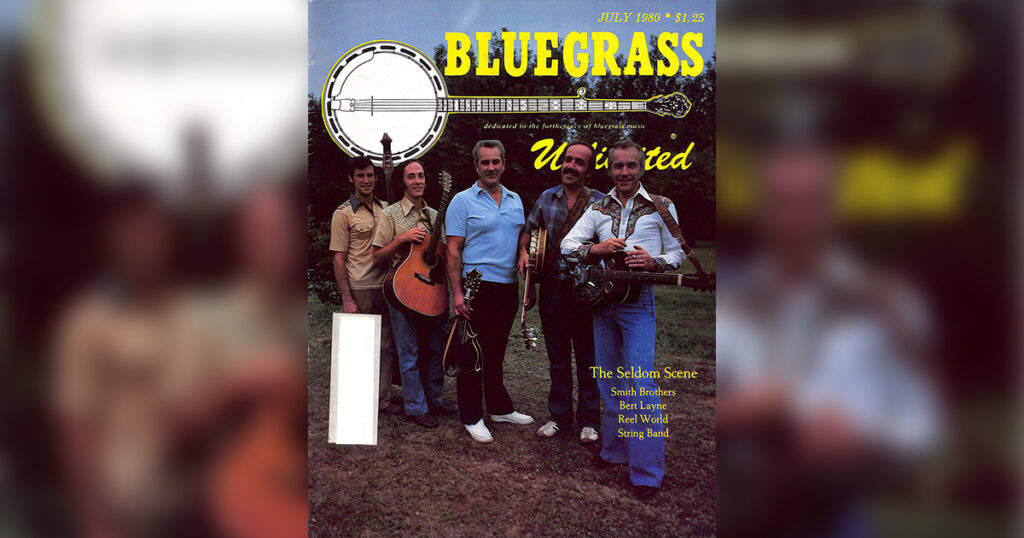

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

July 1980, Volume 15, Number 1

Many years ago, John Duffey attended the annual auction of a post office selling items lost or unclaimed in the mail. Through a low bid, he acquired a large box of broken musical instruments. There among the damaged treasures was Duffey’s first mandolin. In later years, Duffey’s mandolin ability was to become an integral part of The Country Gentlemen and The Seldom Scene bluegrass music groups.

This story is told because it is a good example of the feeling one experiences when hearing The Seldom Scene for the first time in person or listening to their album releases. Just as good surprises fall out of broken Mexican pinatas and just as good fortunes are pulled out of hard Chinese cookies, that’s the way it is with the musical surprises produced by The Seldom Scene.

Bluegrass Unlimited reviewer George B. McCeney observed in discussing the group’s first strictly gospel music album, “Baptizing,” (Rebel Records SLP 1573) that The Seldom Scene has been “unique” from its formation in 1971. He added, “Rarely has a bluegrass band been blessed with such talent from the start, and perhaps even less often has a band been able to stabilize that talent over an extended period.”

The basic secret of the group lies in the words of a publicity sheet distributed by The Seldom Scene which states the members “got together with the avowed purpose of playing for fun.” The same information sheet notes the group’s musicians “succeed by keeping themselves and their music in perspective.” Recently in between performances at Wise, Virginia, not too far from their Washington, D.C., base, Dobro player Mike Auldridge said of the group’s music, “I really believe that we are trying to please ourselves.” Banjoist Ben Eldridge added, “We started this band a long time ago more for our own amusement than anything else, and I don’t think that attitude has changed much. I still look forward to going down to The Birchmere Restaurant in Arlington (Va.) every Thursday night.”

Writers like to make fun of the group’s name in reference to the fact the group makes few appearances due to some of the members having five-day-a-week, white collar jobs. One of the most frequent comments is that the group is “often heard but seldom seen.” That is close to the truth, however, because fans of The Seldom Scene are limited to seeing them in rare concert appearances (rare for a bluegrass group as popular and well-known as The Seldom Scene) and hearing them on the group’s albums. But magnificent albums they are with highly memorable music laid down on round plastic discs by Duffey, Eldridge, Auldridge, John Starling (guitar) and Phil Rosenthal (who replaced Starling on guitar when Starling, an ears, nose and throat specialist, left the group to perform his medical talents in Montgomery, Alabama).

At various times the group has been aided with musical inspiration supplied by such people as Linda Ronstadt, fiddle player Ricky Skaggs (formerly of Boone Creek and now with Emmylou Harris) and Paul Craft (who wrote such classics as “Midnight Flyer,” “Through The Bottom of the Glass,” “Keep Me From Blowing Away,” and “Raised By The Railroad Line”).

One minute you can be hearing the group do Rosenthal’s bluesy composition, “Muddy Water” or his beautiful gospel number, “Brother John,” and a few minutes later you may be hearing a version of the country hit by Tommy Overstreet, “I Don’t Know You Anymore,” or even “Chim-Chim-Cher-ee” from the Walt Disney movie, “Mary Poppins.” Scattered throughout their musical selections are instrumental breaks that put chill bumps on your skin and vocal harmonies so sweet you need a fly-swatter handy to ward off bugs after the nectar.

When The Seldom Scene was formed, Gray was a cartographer (map maker) for the prestigious National Geographic magazine; Auldridge was a commercial artist with the Washington Star news paper; Eldridge was a mathematician for a small company in Arlington, Va.; Starling was an Army surgeon and Duffy had an instrument business. Today, with Starling gone, Rosenthal in and Auldridge laid off due to economic reasons, only Gray and Eldridge continue to hold regular-hour day jobs.

“It’s a security blanket,” Gray commented on his work with National Geographic. “I’m too cautious a person to quit my job for the glory of being a full-time musician.”

Due to the group’s regular nightclub work, popularity at concert appearances and successful album sales, none of the members of The Seldom Scene apparently are hurting financially.

Duffey, Auldridge, Eldridge, Gray and Rosenthal all regard themselves on equal footing in the band. It’s not like Bill Monroe fronting The Blue Grass Boys or special billing like The Earl Scruggs Revue. Still one of the best known persons in the group is John Duffey, partly because of his humorous stage remarks, partly because of his special vocal sounds and partly because of his skill on the mandolin.

In introducing “Bringing Mary Home” to a recent audience Rosenthal noted, “John Duffey had a part in writing this tune. It made him the rich man he is today. It’s a scary tune. John said he saw the story on the television show, ‘Twilight Zone.’”

When Duffey finished the story-song about a hitch-hiking woman ghost to loud cheers and applause, he commented, “Thank you. I’ve had a soft spot in my wallet for that song.” Later as the group neared the end of its performance for that time period, Duffey said, “We’re about to be given the hook here. We’ll do another gospel thing for you.” At that point, a man’s voice in the audience shouted, “I want you to get serious,” apparently in reference to Duffey’s joking on stage. Duffey, unruffled, shot back, “I am getting serious. We’re setting the stage for The Lewis Family!” The Seldom Scene quickly went into a gospel music medley featuring “Amazing Grace,” “Get In Line Brother,” “Swing Low Sweet Chariot” and “I Saw The Light.” The audience was not ready to relinquish their hold on The Seldom Scene so quickly, and after lengthy applause and cheers the group granted an encore.

Backstage, Duffey chatted briefly with Charlie Waller, leader of The Country Gentlemen. It was Duffey along with banjo player Bill Emerson and Waller who helped co-found The Country Gentlemen in 1957.

Upon being complimented on his performance of a few moments earlier, Duffey noted, “When I’m right, I’m turned on and that turns the audience on. When I feel bad, and I go out on stage and can’t sing, it’s like I have got a broken back. I believe an audience should be entertained the best you can do. It seems to me there is always room in the world for a laugh, and I think if you go out on stage and enjoy yourself, it’s going to be contagious.”

Duffey said it is important today for performers to take their musical work seriously because the fans today are very serious when it comes to good music. “Audiences today are more educated, having more knowledge about music. I don’t think you can go out there on a stage and fool them. Twenty years ago, bluegrass music was like pornography. It was sold under the counter. Now it is okay to be a U.S. Senator and say you like bluegrass music. We want to reach anybody who wants to listen to our music, and in bluegrass, your audience age ranges from eight to 80. You have no limited age groups you appeal to in our music. I really enjoy an appreciative audience. Once at King George, Virginia, I thought the people must be sitting on their hands. Pop Lewis of The Lewis Family came backstage and said, ‘Nothing we do pleases them.’ That audience was so dead, on our second show I asked ‘Did we do anything to offend you?’” A guy came up to me later and said it was the best show he had ever seen. I told him, ‘We’d never have known it.’”

When it comes to his singing ability, Duffey said he credits his father with helping him in that area. “My father was an opera singer with the Metropolitan Opera for 25 years. He was 54 when I was born and 93 when he died. He started out as a baritone and ended up a tenor. My father never liked the kind of music I did, and he only came to hear me sing once. After that he told me, ‘Sing out of your diaphragm and not your throat. I took his advice, and it gave me more power. While I don’t like all kinds of music, I can appreciate talent in anything. I never bought an Elvis Presely record, but the man had more talent than a lot of people thought he did.”

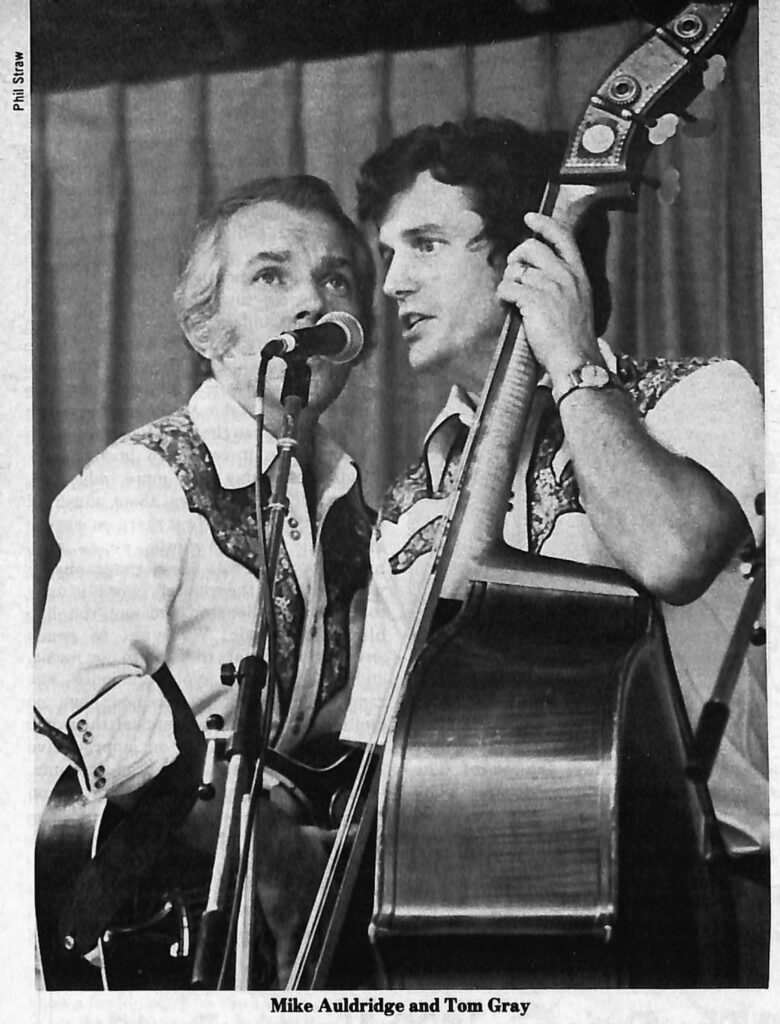

Duffey believes appearing regularly at Washington, D.C., area nightclubs gives the group a challenge. “We know we have a built-in market there, but we don’t play junk for them. We don’t rip them off. It’s like when we do albums. We don’t exactly flood the market with records. If we don’t have the material, we wait because once that finished product comes out on the market, you have to live with it. The only thing we actively solicit is material to record. No matter what some goof-ball may send to us we listen because you never know what you might miss.” While Duffey is known for his wit and mandolin playing, Mike Auldridge is known for his work on the Dobro, not only in conjunction with The Seldom Scene but also spotlighted on his own solo albums and on albums of artists like Linda Ronstadt (‘‘Simple Dreams” album), Emmylou Harris (“Elite Hotel” and “Luxury Liner” albums), Jonathan Edwards (“Sailboat” album) and James Taylor (recently recorded).

Auldridge seems to have the most cool and businesslike manner on stage. This isn’t to say the other members of the group act like fools. There is just something about his stance and facial expressions that make him appear almost detached from the rest of the world; as if intense concentration on his music is all that matters.

“I’ve done about 50 to 60 albums with different people,” Auldridge said in observing that being laid off three years ago along with some 700 other people working with the Washington Star newspaper was a blessing in disguise. “It sure gave me more time to do session work. People began to realize I could fly out to L.A. in the middle of the week, do some recording and get back with The Seldom Scene for the weekend.”

His own work on his solo albums is indicative of the versatility of all members of the Seldom Scene. For instance on the cover of his “Mike Auldridge” album (Flying Fish Records FF029), it states the music contained within explores “the boundaries of bluegrass, country and blues.” The album has such diverse selections as “Last Train To Clarksville” (done by The Monkees and Bluegrass Alliance), “California Dreamin’ ” (done by The Mamas and Papas) and “Georgia On My Mind” (done by Ray Charles).

A classic example of how members of The Seldom Scene think of themselves as five fingers of a working hand rather than as a thumb with four fingers came when a lady fan walked up to Auldridge talking with this writer. The lady fan indicated John Duffey standing nearby and gushed, “Is he the leader of the band?” Auldridge looked at me, smiled and said to the lady, “Well, yeah, kind of…” Obviously on one hand, Auldridge wanted to help the lady but on the other hand he did not want to admit there were any self-proclaimed leaders in the group.

“I honestly don’t feel any desire to play old timey licks on my Dobro. I feel I have a style of my own. I feel like the Dobro could have been used better on the old records. My approach is to play any kind of music on it,” Auldridge remarked after the lady left. As for future Seldom Scene shows, Auldridge noted he took up the pedal steel guitar four years ago and wants to include it on Seldom Scene appearances.

It was member Ben Eldridge who was there when the roots of The Seldom Scene began. Around 1960 Eldridge, as a math major and banjo player at the University of Virginia, had formed a musical acquaintance with John Starling, a pre-med major and guitar player. Also on the campus at the time was Paul Craft, later to write many country, gospel and bluegrass music hit songs. “I went with Paul to Charlottesville, VA., and helped him pick out his first banjo. I taught him how to play it, then he went off with Jimmy Martin for a year and came back and taught me things,” Eldridge recalled.

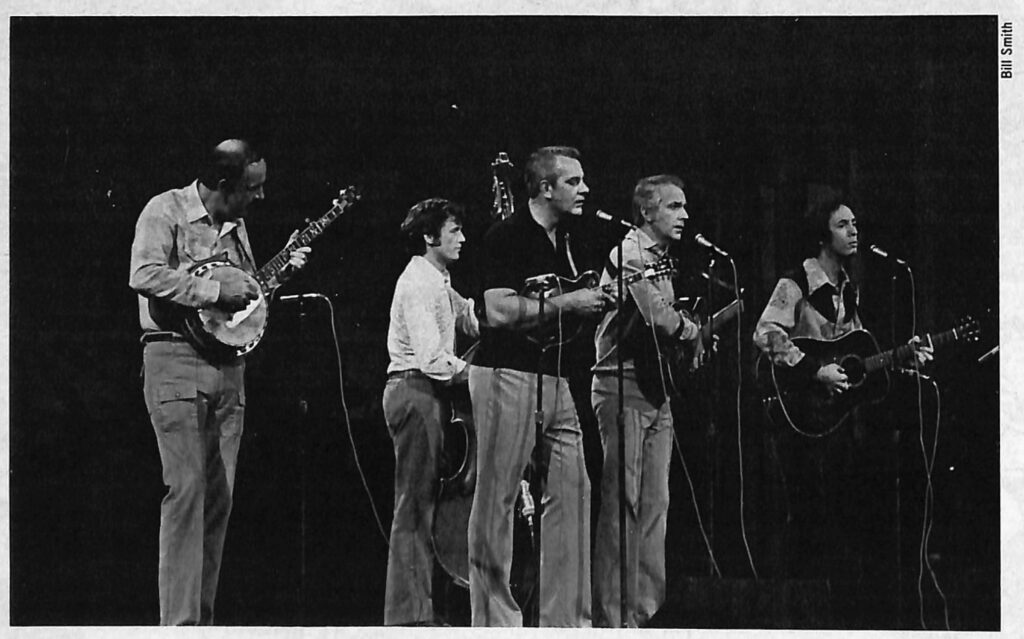

Starling ended up doing intern medical work in Washington, and Eldridge ended up working for a technical engineering firm near Washington called Tetra Tech. About 1967 they formed a play-for-fun bluegrass music band which also included Mike Auldridge. Starling went to Vietnam for a while, and when he returned the musical and personal friendships with Auldridge and Eldridge resumed. Eventually, Duffey and Gray came into the picture and that’s how The Seldom Scene was formed.

At the same time John Duffey, Charlie Waller and Eddie Adcock were with The Country Gentlemen, there was another member of that group who later found a special place with The Seldom Scene. At the time he joined The Seldom Scene in 1971, upright bass player Tom Gray had been almost inactive in bluegrass music for some seven years.

In 1960, Gray had gone to work for both National Geographic magazine and The Country Gentlemen. After three years, he quit the magazine to be a full-time musician. That lasted about a year until his bills started coming more often than his bookings. So, he quit The Country Gentlemen in 1964 and went back with National Geographic full time. Even in spite of the success of The Seldom Scene, Gray said he does not want to give up his “security blanket.”

“Around the mid-1960s, there were no bluegrass music festivals and the only work for our group was in college concerts and in folk music nightclubs. Folk music was big in the late 50s and into the early 60s, but by the mid-60s it was dying out. I think if the situation was like today with bluegrass music so popular, it would have made a difference,” Gray recalls.

Gray said he became interested in map making because he learned early in life that math and geography were his best subjects. “My father encouraged me to apply at National Geographic. They told me when I applied that I was starting at the top. I began as a paster, gluing names on maps, and I later got into other phases like drafting, color separation and compilation. For five years between 1973 and 1978, I worked on a series of 15 maps called ‘Close-up U.S.A.’”

Several music critics have credited Gray with altering the role of the bass in bluegrass music as it applies to other instruments in a bluegrass band.

The group’s newest member, guitar player, singer and songwriter Phil Rosenthal, joined The Seldom Scene in September of 1977. He credits The Seldom Scene recording his composition “Muddy Water” with leading to his acceptance among the Seldom Scene fans. “The first date I worked with The Seldom Scene was in a Washington nightclub. Of course I was nervous because John Starling had been so well liked. It was difficult trying to come into the group as his replacement when he decided to move to Alabama. When we did ‘Muddy Water’ and the audience was told I had wrote the number, they went wild during the song. It was like their way of showing their approval of me.”

Duffey says of Rosenthal’s vocal contributions to the group, “His voice is almost too smooth. Mike and I want him to take up smoking to get some gravel in his voice.”

On the “Baptizing” album, Rosenthal’s songwriting ability is exhibited in the numbers “Brother John” (destined to be a classic), “Take Him In” and “Walk With Him Again.” Prior to joining The Seldom Scene, Rosenthal had displayed his talents performing with a group called “Old Dog,” which also included his wife, Beth, and Mike Auldridge on recording sessions and with another group called “Apple Country.”

Rosenthal moved to Nashville for seven months in late 1974 and early 1975 and learned something valuable about that city. He related, “You spend most of your time making appointments with secretaries. I found out that Nashville life was not for me.”

In the nearly nine years of The Seldom Scene’s existence, they have become more than a musical group joining together for a night of fun. Most bluegrass history observers would agree they have become a major force on the bluegrass music scene. Their successful appearances at such places as Constitution Hall, The Smithsonian Institution, The Grand Ole Opry, college campuses, major bluegrass festivals and The White House lawn before President Jimmy Carter have shown they can stay at home during the week and still be one of the top groups in America today.

Rosenthal writes in his “Take Him In” gospel song: “When He knocks upon your door, take him in. He’ll change your life forever more. Take him in.” Well, if you have a chance to see or hear The Seldom Scene, take them in. They may not change your life forever more, but they’ll sure give you some moments of musical enjoyment.

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

The Seldom Scene arrival as originally constituted was the best thing that ever happened to acoustic music and their ability to encompass other genres to their way of playing is obvious. All but ONE of the original band are deceased and the group using that name now should be called seldom seen IMHO.Retire the name forever and be happy for what once WAS.