Home > Articles > The Archives > Barry Poss and Sugar Hill Records

Barry Poss and Sugar Hill Records

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

October 1982, Volume 17, Number 4

Ten years ago, if a gypsy fortune teller had told Barry Poss that he would someday run a small but successful record company with the unlikely name of “Sugar Hill,” he probably would have laughed and asked for his money back. Ten years and a lot of bridges later, Barry’s still laughing, but now he laughs with glee over the response that his growing catalog has received.

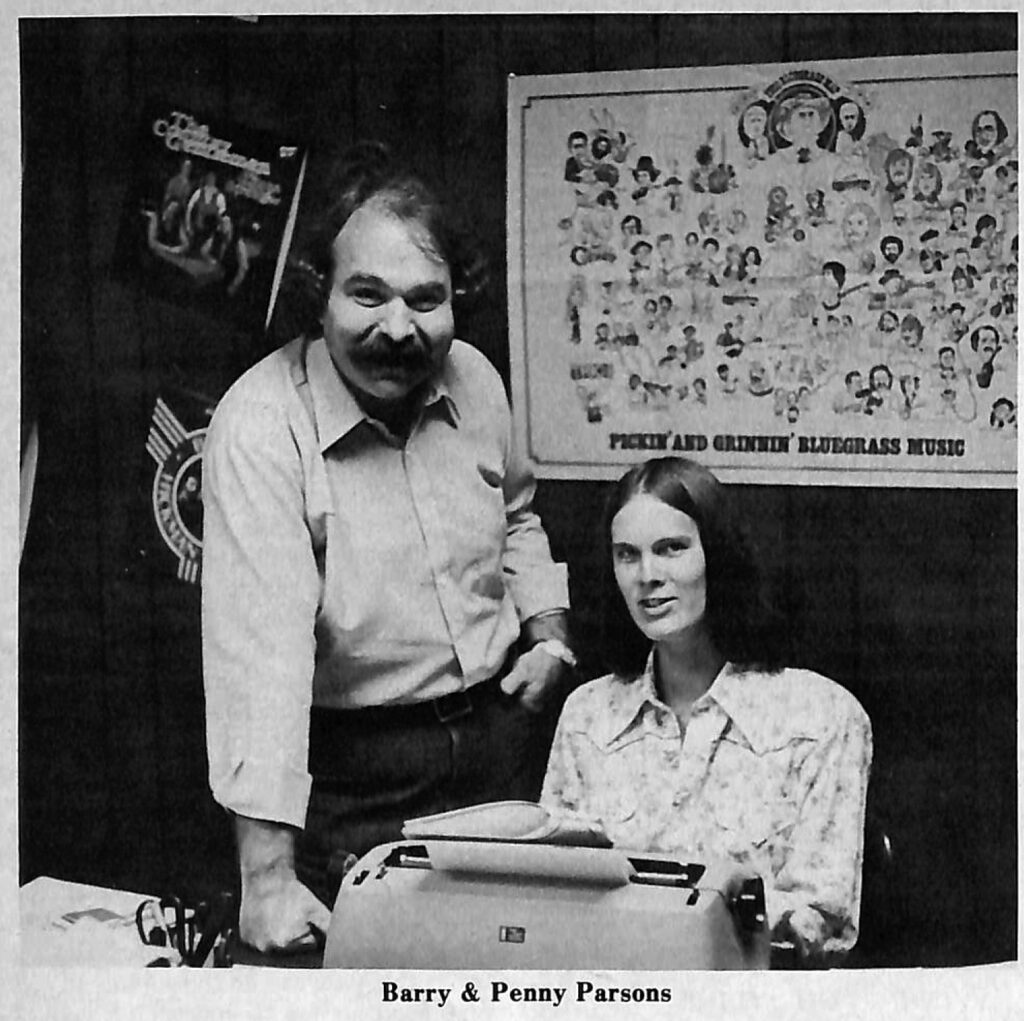

I had known Barry from the days we both haunted the fiddler’s conventions that were spread out over North Carolina and Virginia in the summer months. Back then, Barry was a rather round fellow, with an enormous walrus mustache hiding a wide grin. You could bet that wherever you found Barry, his old-timey banjo would not be far away. Barry still plays the banjo, but now, you’re more likely to find Barry Poss talking “records.” As head of Sugar Hill, “records” have become a seven day, twelve months a year, all consuming project.

While passing through Durham, North Carolina recently, I took the opportunity to stop and pay a visit on Barry. I wanted to keep in touch with him to find out what new tricks he was up to. Most of all, I was intensely curious how he’d done it. When I knew Barry last, he was getting his Ph.D. in Sociology. Now it’s a record company! After slapping each other on the back a few times, we decided to adjourn to his home a few blocks away from the office where we’d met. He said the office was hectic and we’d never get to talk with the phone ringing all the time. As we walked into his home, we were greeted by an antique Wurlitzer juke box occupying a position of honor in the living room. “Isn’t it great?” he asked. Here was a man proud of his juke box.

It wasn’t long until our conversation veered back to my primary and insistent question: “how had he done it?” How had he leaped into the very competitive and financially precarious record business, and how, after such a short existence had Sugar Hill forged to the front and become one of the most exciting and successful young record companies?

The answer begins with Barry’s deep background in traditional music. “My wife Sharon and I got involved in old-time music when we moved to Durham, North Carolina in 1968. We went to Union Grove the last year it was still held at the old school house. I remember being impressed with Wade Ward playing with little Jimmy Edmonds. We started listening to local bands such as the New Deal String Band, and also met and listened to Tommy Thompson, who had a band called the New Academic String Band, with Jim Watson and Fiddlin’ Al McCanless. We came into the music at the beginning of the second generation of old-time music in Durham while there were still the famous Friday night music parties at Tommy Thompson’s house. I then took a few lessons on old timey banjo from Tommy and I was hooked. Banjo and old-time music became an all-consuming thing. Sharon, who played guitar, and I traveled every weekend to visit the old- timers who still played the old-time music. We learned from Tommy Jarrell, Fred Cockerham, Kyle Creed, and people like that.

“By this time I had finished all my graduate course work and all I had left to do was my dissertation. This was in January of 1970 or ‘71. Unfortunately, a dissertation is something you can put off forever, which is exactly what I did. Tom Carter was a graduate student in folklore in Chapel Hill, so he and I used to get together in the middle of the day and play old-time music. I spent a lot of time doing field recordings of traditional musicians and going to fiddlers conventions. There was little pressure to do what I was supposed to do.

“In 1974 or 75, Sharon was playing guitar with the Fuzzy Mountain String Band, and I joined up with Ernest East and the Pine Ridge Boys playing banjo. At that time they were winning prizes everywhere they went, so it was really a thrill for me to start playing with them. It was a funny thing that by playing with them, I started winning banjo ribbons just by association. That success was pretty fleeting, because after I’d played a few summers with them and quit, I stopped winning a lot of the ribbons. I thought I was playing exactly the same. Then Sharon and Fred Cockerham and I played several festivals and did a little tour together as the New Ruby Tonic Entertainers. A little later, I joined the Fuzzy Mountain String Band for its final days. I guess I ended the band,” he said with a laugh.

“Also around 1974 I read in Dave Freeman’s County Sales Newsletter about an opening at County Records for a graphic artist. On a trip to Blacksburg, Virginia, I stopped by to see Dave and talk about the job opening he had. I told him that I didn’t have a clue about graphic arts, but that I knew I could get the job done. I really think that Dave was more interested in finding someone who shared a genuine love and appreciation of the music than anything. Even though what Dave needed in the immediate sense was someone who could get some graphic work done, in the long run, he needed someone familiar enough with the music to help him in the production of new records. That was something I was very excited about. Before I came along, there was Richard Nevins and Charles Faurot. I more or less picked up where they left off.

“Now that I think of it, it’s funny to remember how nervous I was when I went to meet Dave Freeman for that first interview. My only previous exchange with Dave was a stiff letter I had written him some time back. He reviewed an album called “Galax 73” (an anthology of pickers at the 1973 Galax Fiddlers Convention), and Dave rightfully gave it a lousy review. But he said in the review that since there were no performers’ names attached to any of the songs, just one big list of names and a list of the songs, that he thought that the album was making a political statement and said something to the effect that this was some sort of hippie production. In my letter to Dave I told him that I didn’t want to be identified with someone else’s music on the album and I was quite sure that no one else would want to be associated with mine. I was simply taped while I was practicing before going onstage at Galax and that was the first and last thing I knew about any record. Dave wrote back a very nice letter apologizing for his review. To my relief, Dave apparently didn’t associate me with that episode.

“So Dave took a chance and hired me. I had virtually no experience, but a lot of enthusiasm. I knew a lot of musicians in the area and knew I could get the work done in terms of redoing some of the old covers, which I did. Between 1975 and 1978 I coordinated getting new jackets done and began producing some old-time and bluegrass records.

“Part of my job as producer was figuring out how best to approach traditional performers in a recording situation. I think it’s important for a producer to make some decisions about what it is you’re trying to get and why you are there. In recording a traditional performer you’ve already removed him from his natural setting of playing for and with friends. So get rid of all this excess baggage that says this music is recorded ‘naturally.’ My feeling is that a producer is entrusted with presenting a performer to an audience, most of whom will never see that person. There’s no way on vinyl you can share all the wit and humor and personal emotions that are involved with knowing the individual performer on a first name basis. What you can share is a first rate performance. And I think you owe it to the person you’re recording that you try to find a way to get that. The main thing is to be sensitive to what a musician is used to performing and in what kind of situations. You also have to be sensitive as to how delicate one’s ego might be.

“Typically, traditional performers will say, ‘Well, if it’s OK with you, it’s OK with me.’ I get that a lot. What you have to figure out is which things are really OK and which are not. What you have to be keenly aware of is not what the person says, but what they don’t say. This is sometimes very difficult to do. If you let people know that this is a record, and you should be quite direct about it, I think that most people understand why a recorded performance needs to be a little better. I don’t think people want to hear themselves out of tune, or making a lot of mistakes. Part of the job of a producer is to reduce any anxiety about recording. For example, the John Ashby album was recorded at his old homeplace, a cabin which was kept as a special place for the family. For that, we brought in a professional engineer with portable equipment, Bill McElroy of Bias Recording. I felt John would be more comfortable recording in the cabin than in a studio.

“Among the first records I produced was Tommy Jarrell’s fiddle album, “Sail Away Ladies.” That project certainly started before I got involved, but there were certain different things I wanted to do with that album. I wanted the album to be solo fiddle as planned, but to include also spoken introductions that would have the effect of Tommy giving a fiddle lesson to the listener. I encouraged Tommy to use some tunes he hadn’t thought about recording and to even play one tune twice —the old way and the newer version for comparison. My job was to try to get more of a theme, a concept, to tie the album together. Certainly the idea was not new, but I think we came up with something rather unique.

“It took two sessions, spread apart in time, to complete Tommy Jarrell’s fiddle album. I may have slowed things down a little because I was a little fussy about what I accepted. Sometimes I’d say, ‘I think we can do this again.’ It was very hard for me to approach a man of Tommy’s stature and say, ‘We’d better do that again.’ You have to approach someone like Tommy in a much different way than a session musician working in a twenty-four track Nashville studio. Professionals often do more than one take of a song for any number of reasons. But the old-time musicians, especially the older ones, grew up playing music in living rooms, for friends, where no one would ever dream of asking someone to ‘do it over’ because they missed a note or two. I feel that a performance on a record should be different from what you just happened to play sometime. Though I was uncomfortable being in the position of asking Tommy to do things over, I later decided that Tommy really did want someone to make those decisions. As an artist, he clearly did want his best work on a record.”

Another County record that Barry produced which was recorded out of the studio was the Senator Robert Byrd album. Alan Jabbour of the Folklife Center had recorded Senator Byrd for the Library of Congress. Thinking the quality of the material suitable for an album, Jabbour contacted Barry with the idea of making an album of Byrd. At first, Barry was frankly pretty skeptical. But after receiving the tape, he was impressed and started to work to produce a fiddle album by Byrd. As he explained, “I thought it pretty important that here was a prominent figure who was not only very interested in traditional music, but was actually someone who was keeping the tradition alive and who had a genuine claim to the music. He wasn’t someone being a dilettante, he actually grew up with the music. Not only that, he was playing interesting tunes. So I went up to Washington and met with him, and we decided to do an album. In our conversation, it became clear that it certainly would be my responsibility to make sure the album stood up musically. It couldn’t have the ring of a novelty record, such as ‘the fiddling senator.’ To my surprise, he felt the same way. He didn’t want a novelty record either; it would have to be a serious effort. When I explained that I would have to have certain controls over the reproduction of the record, he concurred entirely. He wasn’t going to tell me how to run a record company, and I wasn’t going to tell him how to run the government. In my mind I was concerned how I would tell one of the highest men in government that a cut or two here or there wasn’t quite up to snuff. But actually, there was no problem at all. If anything, he was more critical than I was. I was prepared to accept some tunes after a few takes, but after twelve takes, he’d sometimes say he thought he could do it better. To my amazement, he was a real perfectionist. He was someone who could play for twelve hours straight. Most of the musicians I work with are professionals who warm up a little for a session, but at the same time, are careful not to burn themselves out. Senator Byrd is just the opposite. His way of preparing for a session was to play for twelve hours! When we went to Nashville to do the PBS special on the Grand Ole Opry, he played non-stop from the moment we got there until the moment we left. He twin fiddled with Howdy Forrester, he played with the band, he played with Roy Acuff. I was pretty impressed with how critical he was of his own playing.

“For the recording, I hired Doyle Lawson, James Bailey, and Spider Gilliam. Part of the reason that Doyle came to mind was that he was a genuinely nice guy who would be easy to work with and sympathetic to what was going on. All the musicians were that way. Because I knew that Senator Byrd would be more comfortable outside a studio, I hired Bill McElroy, who built a remote unit specifically for that session. We recorded the whole album in Washington on a Saturday and Sunday. As it turned out, that record has been one of the best selling records for County. Because of that album a good many people have been introduced to traditional music who might otherwise never hear it.”

In addition to a deep interest in traditional music, Barry Poss had an equal passion for the more contemporary side of bluegrass and country music. He remembers, however, his first experience in Nashville with regular studio session players. “It was pretty intimidating at first, especially because I knew a lot less about what was going on than the people I had hired to play.

“Nashville session players are an interesting group. I remember when we did the western swing side of Bobby Hicks’ album for County, he hadn’t even met most of the musicians I had hired for the sessions until we arrived at the studio. When we first got there the guys were real cool. Except for Buck White and Buddy Emmons, the others didn’t know who Bobby was. I think they may have been prepared to go through the motions of another ‘ho hum’ session. But it’s really not the case, as people often suggest, that the studio musicians always do stock stuff. It’s really the producers who ask them to do that day in and day out. They can really cut loose if they’re turned on by the musician they’re working with, and given the freedom to do so. The amazing thing is that they really got excited by Bobby. You could really feel the difference from the time when Bobby walked in and nobody knew what to expect, to the time when he started to lay down a few tracks. All of a sudden they really got into it.

“Bobby’s album probably fits more with Sugar Hill than with County. And in a sense, that was one of the albums that made us see even more the need for Sugar Hill. County had a long standing reputation as a traditional label. Dave was proud that the label stood for something. As much as I love old-time music, I also had an equal interest in newer music. I was really fascinated by people who were fairly young and were listening to and playing contemporary music but who had a firm footing in roots music of some sort. You couldn’t really deny their 1970s and ’80s existence, but what made these people special was that they had this background in the older music. I think that gave them a better understanding of the music. They could use the older music in making their own music. One of the things that makes Sam Bush so interesting, for example, is that he can do all the progressive stuff, but at the same time, I can walk into my living room and put on an old Union Grove Fiddlers Convention LP of Sam Bush playing ‘Sally Goodin’ in a Texas fiddle style that would knock your hat off. Obviously, (Ricky) Skaggs is another perfect example. It’s that foothold in the traditional stuff that gives them a better way of dealing with the contemporary material.

“With that in mind, and knowing Dave’s desire to keep County a standard for traditional music, it was becoming clear that a new label was called for. The kinds of projects I was getting involved in also helped to determine that another label was going to be necessary. Dave had worked with Buck White in the past. Buck was interested in doing a straight country album, and this too would fit better on a separate label. It was time to take the plunge. Sugar Hill was not a subsidiary of County, although when it was first written about, it was presented that way. Dave runs County and Rebel and I run Sugar Hill, but there’s a shared interest in each other’s activity. We still work closely together. I’ll handle certain things for Dave, and he’ll do the same for me. The warehousing, for example, gets handled for both companies in Floyd and Roanoke, Virginia. There are definite advantages in using each other’s expertise.

“I remember a couple of weeks of floating around with different names for the new label. It was getting ridiculous and to the point where I was about ready to toss names down the stairs and see which one landed at the bottom. I finally took the name ‘Sugar Hill’ from the fiddle tune of the same name. I later discovered that Sugar Hill was an area of Harlem, and that there’s a black disco group named the Sugar Hill Gang. We get calls for them constantly. Tommy Jarrell often points to an area in the mountains he calls ‘Sugar Hill.’ Around here, ‘Sugar Hill’ is a part of town you go to to have a good time. But I didn’t know all that then. All I knew was that it was a fiddle tune, and it sounded kind of neat.

“I think there are several reasons why top artists came to record for Sugar Hill. There was an advantage in having been associated with County Records. There was a good relationship between Dave Freeman and me. He had an excellent reputation in the business and though I was much newer to the game, I was out there in the field and I got to know and work with the people involved in the music. My interests were genuine, and I think that came across.

“Another thing that worked to the advantage of Sugar Hill was our size. Even now, Sugar Hill has a relatively small catalog. One of the ideas of Sugar Hill was not to release a lot of albums every month. We concentrate on slow growth and restrict ourselves to top quality projects and, for the most part, known groups. We have mostly recorded groups and individuals who are at the top of their field and concentrated on producing what I hope are top quality albums. Sure, there have been some hits and misses, but overall, I think the catalog stands up.

“There are a lot of artists who choose not to be on a major label because of what they have to give up to do it. In some cases, artists recording on a maj’or label lost artistic control. Sometimes, the frustrations of dealing with a huge corporate structure outweigh the advantages. It’s quite different to be a big fish in a little pond than the other way around. Of course, there are obvious advantages of being on a major label. As a small, independent label, we just don’t have the resources of the major record companies. On the other hand, we also don’t have the same kind of complex corporate decision-making that may not be in the best interest of all artists. Nowadays, for a major label to consider keeping an artist, the break even point has moved up to the 100,000 album level, or in that neighborhood.

“In looking over the Sugar Hill list, there’s a kind of internal logic to the catalog. I think that in our own way, we’re standing for something in the same way that County stands for something. While there’s a heck of a lot of variety there, I think there’s a certain amount of consistency there too.

“You asked me about the Skaggs and Rice album. Tony had called me about doing some recording. Both Tony and Ricky were making names for themselves in other fields, Tony in jazz and Ricky in country. Both have also made a name for themselves in progressive bluegrass. I really encouraged them to make an album that would take that form. Once they had decided to do the duet album, it never really occurred to me that this was going to be a big seller. I did think it would be an important album with these two guys who make such beautiful music to do a traditional album. I didn’t think it would sell as well as if they recorded a more modern album. But that album struck home with a lot of people. You know, it’s interesting that you can feel when something special is happening. We get a lot of people who write in to tell us that they really love this album. I don’t think that people write in to the big labels and say they really love what they’re doing. I think people realize what we’re up against and respond to it. We’re a small company trying to put out quality records, and it’s a difficult thing to do. We want our records to stand up against anything in the record store. The fact that we’re a small company shouldn’t make any difference.

“The Skaggs and Rice album was produced in ‘record’ time. They just got together out in San Francisco and recorded it. There were virtually no over- dubs on that. One of the advantages of working with people of that caliber is that it would be ridiculous to tell anybody what to do. The concept of the album had already been set and the only issue was whether they’d make exciting music, which they did. They acted as their own producers. Sometimes I act as an extra set of ears, but I wasn’t even there. The album was recorded at the Arch Street Studio in Berkeley, a fantastic studio.

“You don’t have to be a real fan of traditional bluegrass to like that album. It is clear that people who don’t particularly like traditional bluegrass are buying the album. At first, people bought the album for who was on it. Later, they bought it for what it was.

“Just like the Skaggs and Rice album, another of our recent releases that has caused quite a stir is the Quicksilver gospel album, “Rock My Soul.” We’ve received enough letters from people who love the album to let us know that something special is happening with that record too. There always seems to be an unwritten rule that after a group does so many albums, it’s time to do a gospel album. That’s been happening in country music for years. For this very reason, many of the gospel albums which groups feel obligated to make are not all that good. The Quicksilver album is getting such good response not so much because it’s a gospel album, but because it’s so good. You know I made a commitment with Quicksilver a lot earlier than I would have with a lot of other groups. This was partly because I knew the people involved. I knew Terry from the Boone Creek days, and I knew Doyle since we recorded his “Tennessee Dream” album for County. With these guys, you just sort of knew that something special was going to happen. This wasn’t a weekend band. They’re all excellent instrumentalists, but it’s hard to find a young band who can sing like that. Their duets and trios and quartets are just fabulous. And it hasn’t come by accident; they really work at it. If you sing great trios and quartets like that, the best place to show that is in gospel music. The choice of material on the record was, I think, excellent. Although there were a couple of tunes that everybody knows, by and large the band took a chance on the material, most of which was unknown. A lot of it Doyle learned when growing up around Kingsport, Tennessee.

“I think it is very important for groups to learn to do things simply. There’s a real lesson to be learned by subtlety and understatement. It’s especially important for bands just starting out to resist getting complicated too soon. You’ve really got to master the complex job of getting at the elegance of simple arrangements. On the Skaggs and Rice album, I don’t say ‘Where’s the rest of the band or the third harmony part?’ The same is true of the Berline/ Crary/Hickman album: it is complete in and of itself. Of course, where a piece does call for a more complex arrangement, you’ll know better what to add and what to leave off and generally how to make the arrangement work for you. The Seldom Scene have come up with some very complex arrangements, but still sound and feel elegantly simple. Country music in general is always going in two directions at the same time. It’s always becoming more progressive and it’s always returning back to roots too. In the case of bluegrass, there are bands experimenting with new sounds while at the same time, new groups like Dave Evans and the Johnson Mountain Boys are reaching back to a more traditional sound.

“What interests me about Sugar Hill is that we’re recording artists with firm roots in traditional music who are experimenting with more modern sounds. I like the fact that we’re able to pay attention to each new release and I like the fact that most people know most of the stuff that’s on our label. That’s real important to me. Of course, in about ten years, that will change, but I’m not out there trying to produce as many records as I can. We get a fair number of letters from groups wanting to record for Sugar Hill. That’s probably the toughest part of this job. I’m still a music fan and when I go to a show and tell the performers that I liked what they did, I don’t necessarily mean that I want to do a record. For us to survive, we depend on all our distributors taking our albums. A group that is known only in Kansas City, for example, would have difficulty selling their record in California. The distributor out there just isn’t going to take it. So it’s a matter of economics, as much as anything. For that reason, we’re pretty much restricted to groups that are either touring full-time or known on a national basis. It’s still hard to respond to all the groups that write in. I’d like to do more than I do, but the economy’s in terrible shape. Like it or not, records are a luxury. But I’m not that concerned with expanding that much. There is a kind of internal growth with the acts that we now have. Of course, if something excited me musically, sure I’d consider it.

“I guess it’s that special record that comes along all too rarely that makes this all worthwhile. After you’ve been in the record business for a number of years another record is just another record. I hope that will never happen to Sugar Hill.”

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Wonderful to read this. I don’t recall whether I had read this back at the time or not. I really loved the story of how Barry first got hired by Dave Freeman.

Dave was also very helpful in inspiring Rounder Records to get started.

I had just been thinking of Barry about 10 days ago. Wish I had reached out to him….

Thanks for making this available again.