Home > Articles > The Archives > Red Allen—David Grisman Bluegrass Reunion

Red Allen—David Grisman Bluegrass Reunion

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

May 1992, Volume 26, Number 11

To David Grisman, bluegrass is more than just an itch that he needs to scratch occasionally; it’s an integral part of his being. Each encounter is like a passionate reunion with a first lover. He fondly recalls the first kiss: “It was a record of Earl Taylor and the Stoney Mountain Boys singing ‘White House Blues.’ I was blown away. I couldn’t believe anybody sounded like that.’’

Galvanized by the speed, sound and authenticity of the music, the then sixteen-year-old city boy discovered an unlikely discipline he could believe in—bluegrass mandolin. Within an unreasonably short time period he was the hottest young mandolinist around, subbing or playing with bands such as the Kentucky Colonels and Red Allen and the Kentuckians, while sitting in with legends. It’s said that even the man himself, Bill Monroe, tacitly acknowledged David as an heir-apparent. But in 1967, at age 22, Grisman abandoned the bluegrass life, citing lack of support and headed for California. He took what he learned from his mandolin mentors—Monroe, Frank Wakefield and Ralph Rinzler—and parlayed it with countless other musicial inspirations to create his ground-breaking instrumental ensemble Dawg music. In the process he became one of the world’s best-known mandolin players. Through all of his smooth mixture of jazz, classical and ethnic sounds, however, bluegrass lies at the very root of his music and he takes his encounters with it seriously.

Over the past 25 years, Grisman has seldom gone long without some kind of bluegrass fix, turning up as a guest at festivals or performing on one of his many talented friends’ albums. He’s even put a few one-shot and short-term bands together for special occasions, including 1972’s notorious Old & In The Way with Jerry Garcia, Vassar Clements, Peter Rowan and John Kahn. His best efforts, however, have been on his own records dedicated solely to the idiom, starting with 1980’s “Early Dawg’’ on Sugar Hill. (Grisman considers 1972’s legendary “Muleskinner” album with Rowan, Clarence White, Richard Green and Bill Keith to be hybrid bluegrass. A delightful selection of bluegrass and nascent Dawg tunes, “Early Dawg” presents Grisman in total command of the idiom. He is accompanied by Keith, Wakefield, Del and Jerry McCoury, Artie Rose and Winnie Winston.

Grisman’s next foray came in 1982, when he gathered Herb Pedersen, Vince Gill, Jim Buchanan and Emory Gordy, Jr., under the banner of Here Today for several live performances and an outstanding eponymously titled Rounder album. Six years passed before the next excursion, a sparkling Rounder two-CD package, “Home Is Where The Heart Is,” that was nominated for a Grammy. The all-star set features Red Allen, J.D. Crowe, Sam Bush, Tony Rice, Porter Church, Mark O’Connor, Curly Seckler, the Nashville Bluegrass Band, Ricky Skaggs, Roy Huskey, Jr. and Doc Watson.

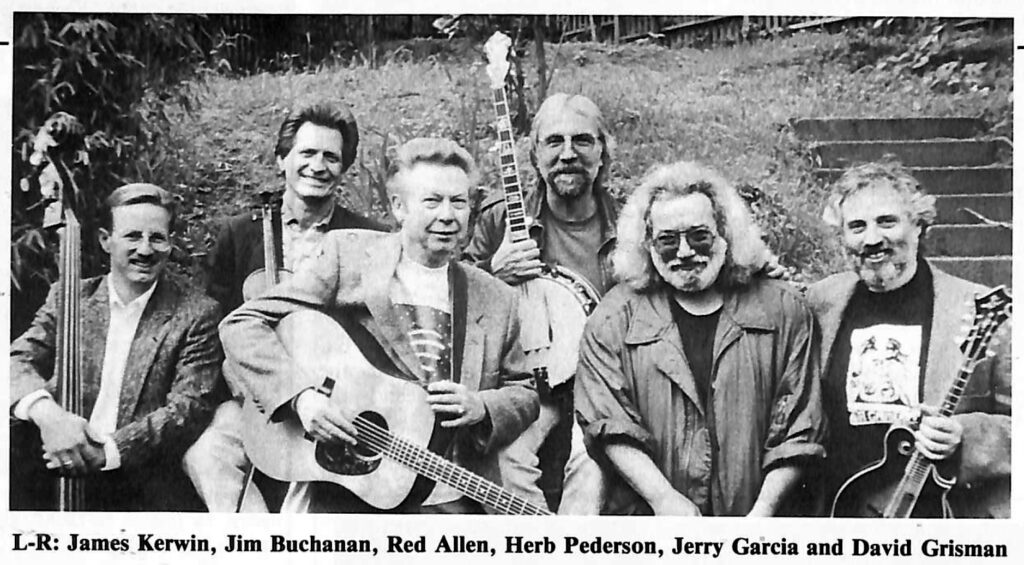

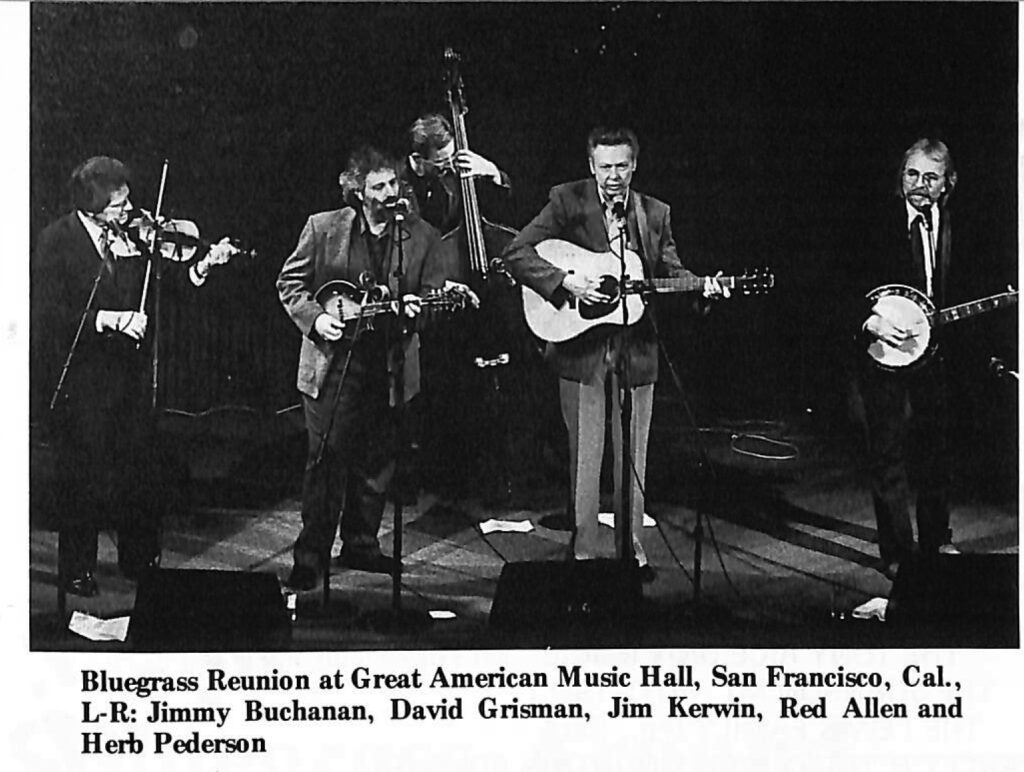

Now the Dawg checks in with his latest entry, “Bluegrass Reunion,” a sixteen-cut gem that summons ghosts of the golden age of bluegrass. As the name implies, Grisman assembled a band of musicians he has worked with in the past (though never all at the same time), including Allen (vocals, guitar), Pedersen (vocals, banjo), Buchanan (vocals, fiddle) and his longtime bassist James Kerwin. In addition, special guest Jerry Garcia contributed vocals and guitar on three cuts. The impetus was a last-minute request from the organizers of California’s Strawberry Bluegrass Festival. “They needed another act for their spring festival and asked me to put a band together,” says Grisman. “So, we had this gig and I said, ‘Gee, why don’t we make a record since we have to put a bunch of material together and I’ve got this record company and studio?”

For Grisman, the project closed a circle of sorts. “Red gave me my first job in an authentic bluegrass band,” he explains. “He also gave me my first job as a record producer. Now, I get to hire him and produce a record with him on my own label.” In fact, Grisman produced three Allen LPs in the ’60s, the first at age eighteen (“Red Allen/Frank Wakefield And The Kentuckians Bluegrass,” Folkways). He also played on one of them (“Red Allen And The Kentuckians, County) during his year-long tenure that began in 1965. “Bluegrass Reunion” is the fourth release on Grisman’s own Acoustic Disc label, two of which have won Grammy nominations (“Dawg ’90” and “Garcia/Grisman”).

If the band seems a bit esoteric, i.e., outside familiar bluegrass circles, its credentials are, nonetheless, impeccable. Allen, now 62, has been entertaining bluegrass audiences for more than four decades, coming to prominence between 1956 and 1958 as a key element in the Osborne Brothers’ trademark “high lead” trio sound. Over the past thirty years the Kentuckians, has been a temporary home for many exceptional musicians, including Grisman, Wakefield, Keith, Greene, Bill Emerson, Doyle Lawson, Scotty Stoneman, Bill and Wayne Yates, Tom Morgan, Bobby Diamond and Porter Church. “And,” says Red, “one of the two best baritone singers he ever had was a young banjo player who then went by the name of Pete Roberts [nee Kuykendall].” Allen was also a longtime Saturday night radio fixture on WWVA World’s Original Jamboree at Wheeling, W.Va. His songwriting credits include “Teardrops In My Eyes” and “It Hurts To Know.”

Pedersen’s resume includes stints with Flatt & Scruggs, the Dillards, Vern and Ray and a host of lesser-known bands such as the Smokey Grass Boys, formed with Grisman in the mid ’60s. As an L.A. session player, his banjo, guitar and vocals have graced countless albums and film scores (most recently, City Slickers). Currently, his exquisite paint-peeling tenor and fluid guitar are vital components of Desert Rose, the highly acclaimed country group led by former Byrd and Burrito Brother Chris Hillman. Buchanan, the son of old-time fiddler Clato “Buck” Buchanan, fiddled for Jim & Jesse during their biggest years (1961-66) and later worked with the Greenbriar Boys and now back on the Grand Ole Opry with Jim and Jesse. Garcia began as a bluegrass banjo picker and, by all accounts, had developed serious frailing and Scruggs-style chops before he took up electric guitar to form what would become the Grateful Dead. His craggy voice has all the character of a fifty-year veteran of the idiom. Kerwin has learned the trade playing with Grisman and, despite his jazz roots, displays a savvy feel for the shadings and subtleties of the bluegrass beat.

“Bluegrass Reunion’s” material draws heavily on Grisman’s past experiences with the musicians involved. It begins and ends with “Back Up and Push,” Allen’s longtime theme song used to open and close his shows (much like Monroe’s “Watermelon On The Vine”). Other pieces strongly identified with Allen include “She’s No Angel” and “Is This My Destiny?” from his Osborne Brothers days and “Down Where The River Bends,” a perennial Allen standard. Additionally, “I’m Just Here To Get My Baby Out Of Jail” and “Little Maggie” both appeared on the Grisman-produced Allen/Wakefield LP, while the version of Flatt & Scruggs’ “Is It Too Late Now” was drawn from a live tape of an Allen/Bobby Osborne duet. In all, Red sang lead on nine of the thirteen vocal selections. Other lead vocals were supplied by Pedersen (“Little Maggie”), Garcia (“The Fields Have Turned Brown” and “Ashes Of Love”) and Buchanan (on his own composition “To Love And Live Together”). Grisman provided one instrumental composition, “Pigeon Roost,” named after Allen’s Kentucky birthplace. Not surprisingly, perhaps, the dominant lead instrumental voice is Grisman’s, although Buchanan and Pedersen also made significant contributions. Garcia played lead guitar on two cuts.

Sessions took place over three days in May at Grisman’s small home studio in Mill Valley, Cal., employing the ancient (by current standards) eight-track analog equipment he has used since the early ’70s. Like all Grisman productions, the sound is truly stellar. “The sessions were pretty compressed,” he says. “We played two gigs and made the record in a total of five days. I wish we’d had more time because there are so many bluegrass bands that have been cultivating their trio singing for years. It’s hard to get that kind of precision without putting the time in. I was hoping to get a lot more on tape but Red got tired because he hasn’t worked much in the last few years. Still, we got 48 minutes. Everybody seemed to enjoy doing it. I know Jerry got a big kick out of singing with Red and Herb. I don’t know if he’s sung any bluegrass since ‘Old & In The Way’.”

Pedersen and Allen confirm Grisman’s assessment that a good time was had by all. ‘‘It was the first time I’d seen, much less worked with, Red since 1968,” says Herb. “I was surprised how young and lively his voice still sounds. There’s still a lot of passion there. This project was a real labor of love. I hope we get to do it again.” As for Red, the album proved an impetus to increase his activity, which was slowed by a heart attack a few years ago. He has booked his band at several festivals this summer and is currently participating in a Bill Emerson recording project. One of the most satisfying moments, he says, came at the close of the Strawberry show. “We came off the stage and David walked up behind me and said, ‘You ain’t lost nothin’. When a man plays with you and Del McCoury what is there left?’ That made me feel good. If we’d had about two more dates out there, we’d have really got loose. I can always sing, but the more you do it, the more it limbers up and the better you sound. My guitar lick was there but it wasn’t like it always was. You got to keep up on that guitar, you know. But it was alright. I was well pleased. I really enjoyed singing with Herb and Jerry. They really impressed me. They’re fine fellows.”

Like all previous Grisman bluegrass projects, “Bluegrass Reunion” was done strictly by the book as written by Bill Monroe, Flatt and Scruggs and the Stanley Brothers; no newgrass or innovations here. When it comes to bluegrass, the man who revolutionized acoustic string band music is strictly a traditionalist. “For me,” says David, “bluegrass was perfected in the 1950s and you can’t take it any further than that except on the interpretive level of it’s not Carter Stanley anymore, it’s Jerry Garcia. I haven’t heard anything that’s better than the original thing; you just can’t get past the original vision. That’s a limitation, but once you accept that, you’re home free. Consequently, the contemporary bluegrass I like most is the stuff that pays the most homage to that, such as the Nashville Bluegrass Band, Doyle Lawson and the groups that Tony Rice and J.D. Crowe work with.

“Still, bluegrass seems to be in a healthy state with as many young people getting interested as ever. Things have got to change, I know that, but the precepts need to be studied and adhered to for it to succeed. It’s like classical or chamber music. If you’re going to play it, you have to remain true to that style or ‘else it becomes something different; it’s not that style anymore. I don’t think there are any new places to take bluegrass from a stylistic standpoint. Other things have been done with instruments used in bluegrass, such as what I’m doing with my band, but I don’t consider what I do to be bluegrass. I’m sure Bill Monroe doesn’t either, although some third party might.

“I was lucky; I had the chance to put in some time and study with people like Red Allen and Del McCoury. I got to hear Red, Ira Louvin and Bill Monroe sing trios one afternoon and I played a set with Red Smiley once. Some of it rubbed off. I admit I don’t keep up on the new people that have come along, because I know I’m not going to hear what I got into bluegrass to hear. That’s no knock on them. It’s just that it takes a certain amount of time to be deep and the newer guys just haven’t had the time.

“There’s never been a proper perspective for bluegrass in the music industry, it just hasn’t gained the respect or economic position that it deserves. All those guys were trying to make it in the music business in some form or another. It’s just that at their particular place in history, what they knew was folk music learned from a real oral tradition. I guess there must be something about learning a song from your grandmother when you’re two years old as opposed to learning it off a record or out of a book. No matter what you do it’ll never be the same. But I think what we’ve done on this record is close.”

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Watching him play, the joy he exudes, he is Truly Jolly!! He and I hung out and jammed a bit in Albuquerque New Mexico, show produced by Chuckie Deleonardis of Big River … Grisman is very generous spirit… I will forever be grateful for the excellent time spent, during set up, sound check, and the show… I love the man! He’s just as wonderful and happy off stage as he is playing… the flip of that hair, the roll of his body dancing through every note,

and he plays all the right notes .. love his unique phrasing!!! Thank You David!!

🌻𝒱𝒾𝒸𝓉𝑜𝓇𝒾𝒶 ℒ𝑒𝑒