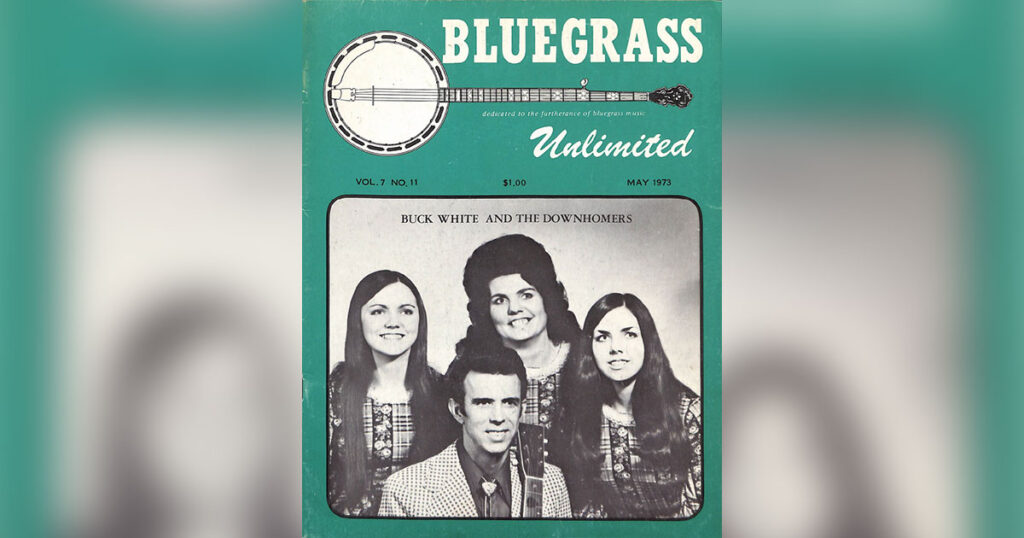

Home > Articles > The Archives > Buck White & The Downhomers

Buck White & The Downhomers

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

May 1973, Volume 7, Number 11

The sprawling, desolate Texas plains have never been the spawning ground of bluegrass talent that the Appalachians have. Involved for years with its own gift of genius to American music—Western Swing—Texas has made bluegrass music fight hard for a toehold out there, even today.

Yet the state of Texas produced one of the most creative bluegrass musicians of our day, largely, perhaps, because of the fertility and the variety of musical forms from which Buck White was able to draw in developing his distinctive style: swing, old-time, blues, western, fiddle tunes, south-of-the-border, bluegrass, and jazz. It is this cross-pollination in his mandolin style which makes his music so refreshing, music which creates an aural excitement that goes beyond technical proficiency.

Buck was born in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, the son of a construction worker, who moved back to his native Wichita Falls, Texas, a few months after Buck’s birth. His father was a semi-professional buck dancer, who also tried his hand at the clarinet and the trumpet, but Buck didn’t begin to try to play an instrument until he was thirteen, when he attempted to take up the drums.

Only one thing stood between him and a career as a drummer—lack of drums. His grandmother did have a piano how ever, and with her help, and that of a local professional pianist named Henry Dockins, he soon put his natural talents to practice. He picked up a few records, and was heavily influenced by the playing of two great blues/boogie-woogie pianists, Albert Ammons and Pete Johnson.

Buck played piano (and its asthmatic cousin, the accordian) all through high school, but “fell in love with the mandolin at first sight”, as he puts it, when introduced to it by a friend, Red Fields. In his senior year in high school, he picked up a Martin mandolin for $40, and shortly thereafter traded it and his fancy accordian in on a Gibson F-12.

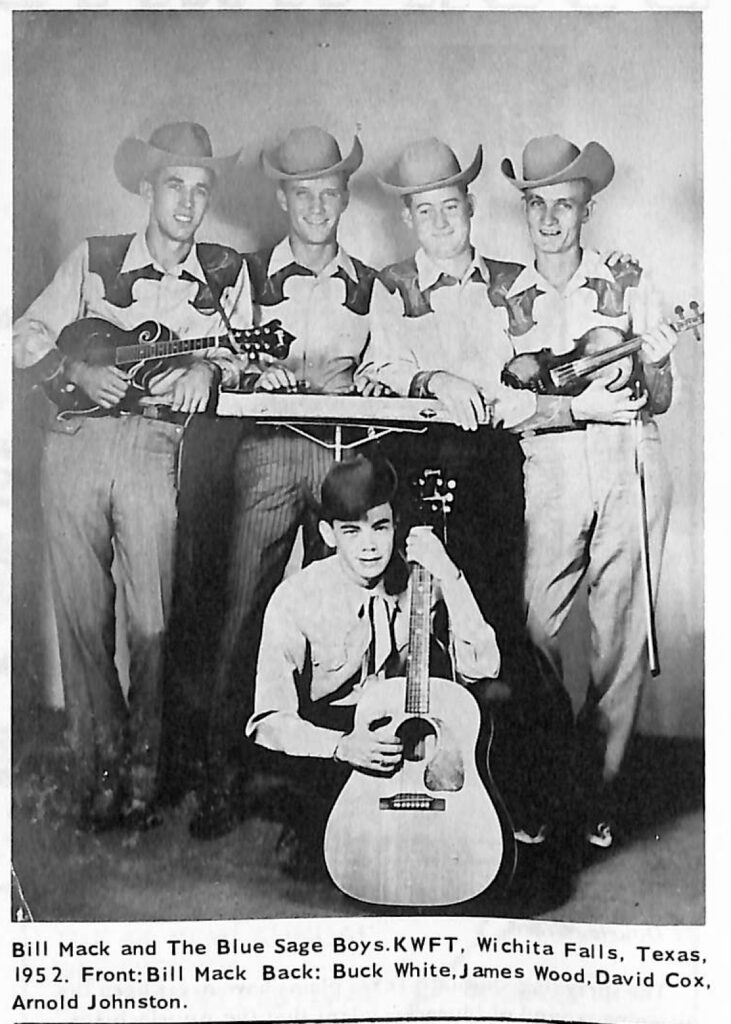

Buck started at Midwestern University after graduation, but gave it up after a semester. He had been in a western/old time band—The Blue Sage Boys—his senior year in high school, and they had been playing a 5:30 AM radio show every morning, while booking out occasional shows in the evening. When the opportunity came for them to move to Abilene in 1950, to become regulars on the newly formed KRBC “Hillbilly Circus”, the youngsters jumped at the chance.

In the year the Hillbilly Jamboree lasted, Buck made many invaluable friends and acquaintances. Here he met and performed with the Callahan Brothers, who reinforced his devotion for old-time music. He also met a number of Nashville musicians who came through town, and was even offered a job with two—Lefty Frizzell and Hank Snow—as pianist.

But another acquaintance he’d made kept him there in Abilene—Bob Goza, a singer on the Hillbilly Circus, whose sister Pat, Buck came first to know, then eventually marry. Pat’s entire family is a musical one, and while Bob has since retired from performing, two other brothers, Frank and Glen, are songwriters and singers today.

When the Hillbilly Circus broke up, Buck stayed in Abilene with Pat and Pete Newman, another member of the old Blue Sage Boys. Buck and Pete went to work, as pianist and vocalist respectively, for a Bob Wills-type Western Swing band headed by Zeke Williams. When this band folded, they headed back to Buck’s native Wichita Falls, where KWFT was beginning a Saturday night jamboree.

Here the Blue Sage Boys were reunited, and were joined by some of the Hillbilly Circus entertainers, such as the Callahan Brothers. The Blue Sage Boys became the backup band for recording artist Bill Mack (yes, the same Bill Mack who is now the super DJ on WBAP in Fort Worth), and together they made hundreds of radio shows, personal appearances, and recordings in 1952-53.

Wichita Falls’ first TV station, KFDX, began a country music show in 1953, which was hosted by a local owner of a western wear shop and famed rodeo announcer named Nat Fleming, and while Buck joined this band primarily as a pianist, he also played a good bit of mandolin and guitar. This show was to last five years. Not only did Buck find time to play this show every afternoon, and play at night, but he operated a small but successful plumbing business at the same time.

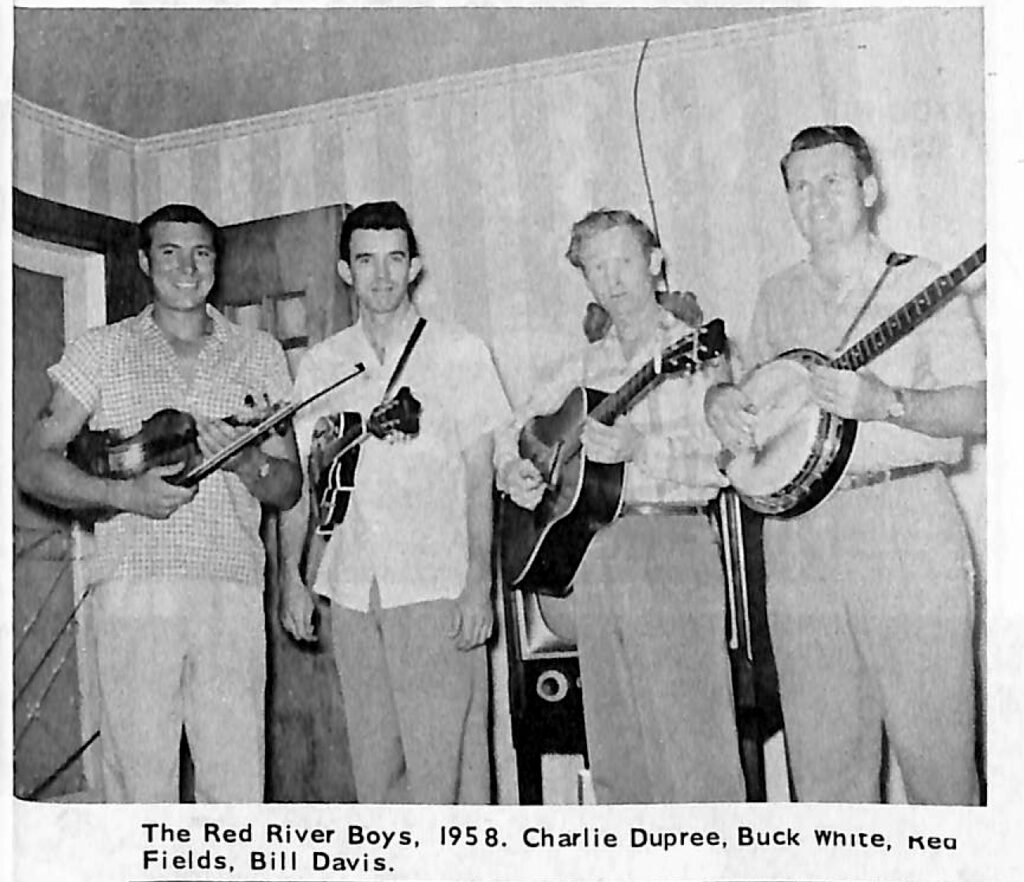

Never one to sit still, he and his old high school friend Red Fields rooted out the only banjo player within a hundred and fifty mile radius, Bill Davis, and the three of them would travel for miles to get together and jam—the first real bluegrass music Buck had ever played, live. They called themselves the Red River Boys, and played when Buck wasn’t busy with the Nat Flaming show. Buck says, “I was playing the piano for money, but the mandolin because I loved it.”

The arrival of rock and roll spelled the end of the Nat Fleming Show, but did provide some rather different employment for Buck: playing electric piano in a rock band called The Volcanoes. Composed of Buck, Kenny Brewer and Alvis Barnett (guitars), John Duckett (bass), and Kenny Graham (drums), they “were a good outfit, too, boy!”, according to Buck. Both good and popular as well, for Buck remembers “We’d leave for five nights and I’d sleep in a bed one night.”

“But,” Buck recalls, “I wasn’t really happy. I was wanting to do something else. But I was making a living at it. I got disgusted with night clubs and dance halls and everything that went with it, and quit music entirely. I moved to Arkansas, out in the country—I wanted to get away from everybody and everything. But … it wasn’t long before I had another band.”

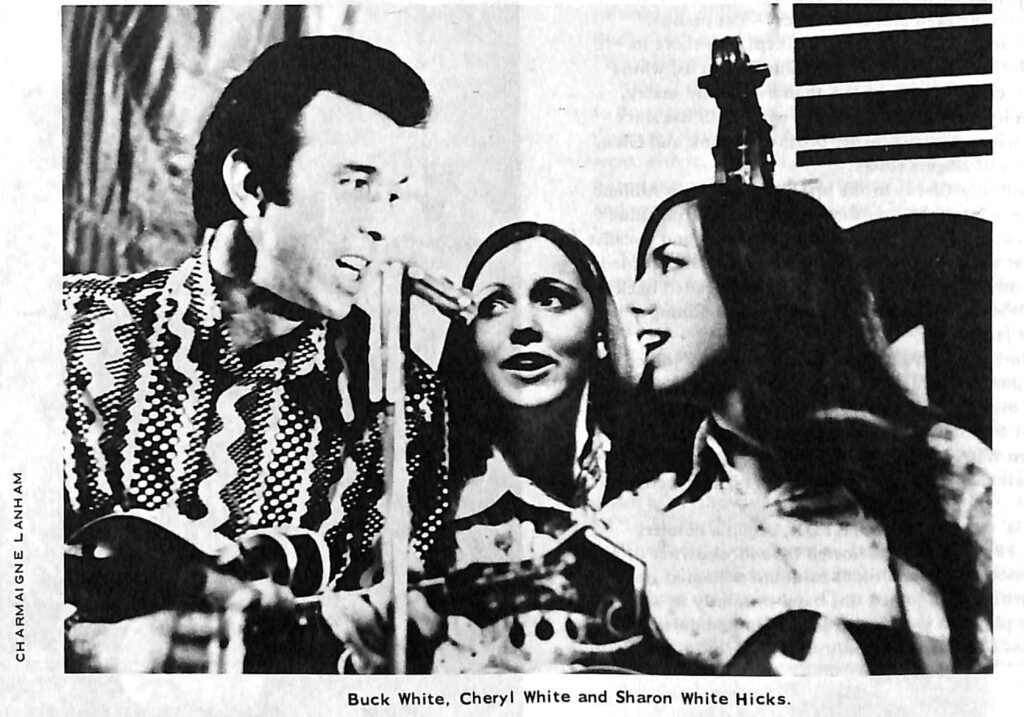

The Whites had moved to Fort Smith, Arkansas, where they were soon followed by Buck’s long time picking buddy and ex-Blue Sage Boy, fiddler Arnold Johnson. Arnold had two boys by that time the same ages as Sharon and Cheryl, Buck and Pat’s two children, who had begun singing when they were eight years old and a little family band was soon formed.

Wanting to keep a wholesome, rural image, they called themselves the Downhomers, and began a weekly Saturday night show in Witherville, Arkansas, and “it wasn’t long before that place was crowded every Saturday night!” They soon began a TV show which they kept for a couple of years on KFSA in Fort Smith.

They were introduced to festivals at the now-legendary second Fincastle gathering in 1966, bringing Ralph Thomas with them on the banjo. They were well received when they made a brief appearance on stage, and this reception nurtured Buck’s growing plans to move to the southeast.

“I had considered moving here before I was offered a job with Hank Snow, but we actually got to coming over to these states when we started going to the festivals. The next year in ‘67 we got on the Walker, Louisiana festival, and that’s where Sharon and Cheryl played their first road show, you might say. They just took to it like ducks to water, and it’s been that way ever since. The bigger the crowd, the better they like it!”

The Whites did eventually move to Nashville late in 1971, and although Buck, to his disappointment, had to return to plumbing to support his family, he and they, individually and as a group, have been quite busy musically nonetheless. They have recorded an excellent album on County (“Buck White and the Downhomers”), and some or all of them have assisted on albums by Kenny Baker, Vernon Derrick, Vic Jordan, and two by this author; they played numerous festivals last summer, and have many more booked for this season; they played regularly at the Bluegrass Inn in Nashville for several months; they appeared on Germany’s Werner Baecker Show (for some thirty million Germans!); and recently auditioned for Don Light (booking agent for Mac Wiseman and the IInd Generation), for whom they’ll soon be doing some shows.

They have also been involved in a crusade of sorts; subtle and unspoken, but real nonetheless, for while Buck has had several opportunities to join other established bands, he has stuck with the family unit tenaciously and with unswerving determination. While it seems at times that bluegrass audiences are reluctant, at best, to accept women in a bluegrass band, the Downhomers continue to persevere.

True, a few women have worked with different bands off and on for years—Bessie Lee Mauldin, Gloria Belle, Penny Jay, Lois Johnson, Sally Forrester and others—have all played with bands of stature. But three women in one band? Never. This is the crux of their crusade—to make their audience

realize that Pat, Sharon, and Cheryl are as good musicians as any, and that their intricate and subtle harmony (which one callous reviewer called a combination of the Lennon sisters and Bill Monroe) can actually add a good bit to bluegrass, as well as being an extremely refreshing change from the ordinary. Judging by their recent good fortune, their crusade must be succeeding they are opening more ears and minds daily.

In a time when bluegrass music is expanding in all directions, more and more people are discovering their unique and fascinating blend of bluegrass, western swing, dixieland and jazz; they are discovering that women can be as capable as men as musicians and singers; and they are discovering that, among the up-and-coming-bands, the Downhomers combine outstanding musicianship, a contemporary outlook, and tremendous vocal ability while maintaining their vital, back-porch, friendly neighbors, down-home feeling.

Share this article

2 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Love the Whites!! I live in Wichita Falls, Texas, but was too young to know them at that time!! But, have their records and CD’s now!!! Will miss Buck!!

Very few family units have blazed a musical trail like the WHITES. Never compromising their integrity, morals and respect for humanity to farther their career. In the music industry those qualities are few and far between when put against the desire for fame and fortune. They did it their way and from 1972 to today I have seen them move from a dream to reality and nothing changed. If anything they became more humble and thankful to their Lord. Buck and Patty have gone home but the girls carry that talent and tenacity with them where they are.