Home > Articles > The Archives > Jake Tullock—The “Forgotten” Foggy

Jake Tullock—The “Forgotten” Foggy

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

July 2015, Volume 50, Number 1

In bluegrass, as in many other kinds of music, the accolades most often go to the singers and instrumentalists that occupy the spotlight. The bass player, who stands in the shadows, often receives little recognition for his or her talent, even though he’s providing the essential foundation that allows the stars of the show to shine. In the case of Jake Tullock, this seems especially unjustified. The multi-talented bassist, harmony singer, and comedian with Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs, and the Foggy Mountain Boys during the height of their fame and popularity, Jake has too often been forgotten as the band’s history has been recounted. Tullock’s bandmates—Flatt, Scruggs, Curly Seckler, Josh Graves, and Paul Warren—have all taken their places in various halls of fame. Yet Jake’s important contributions to what was one of the greatest bluegrass aggregations of all time have largely been overlooked.

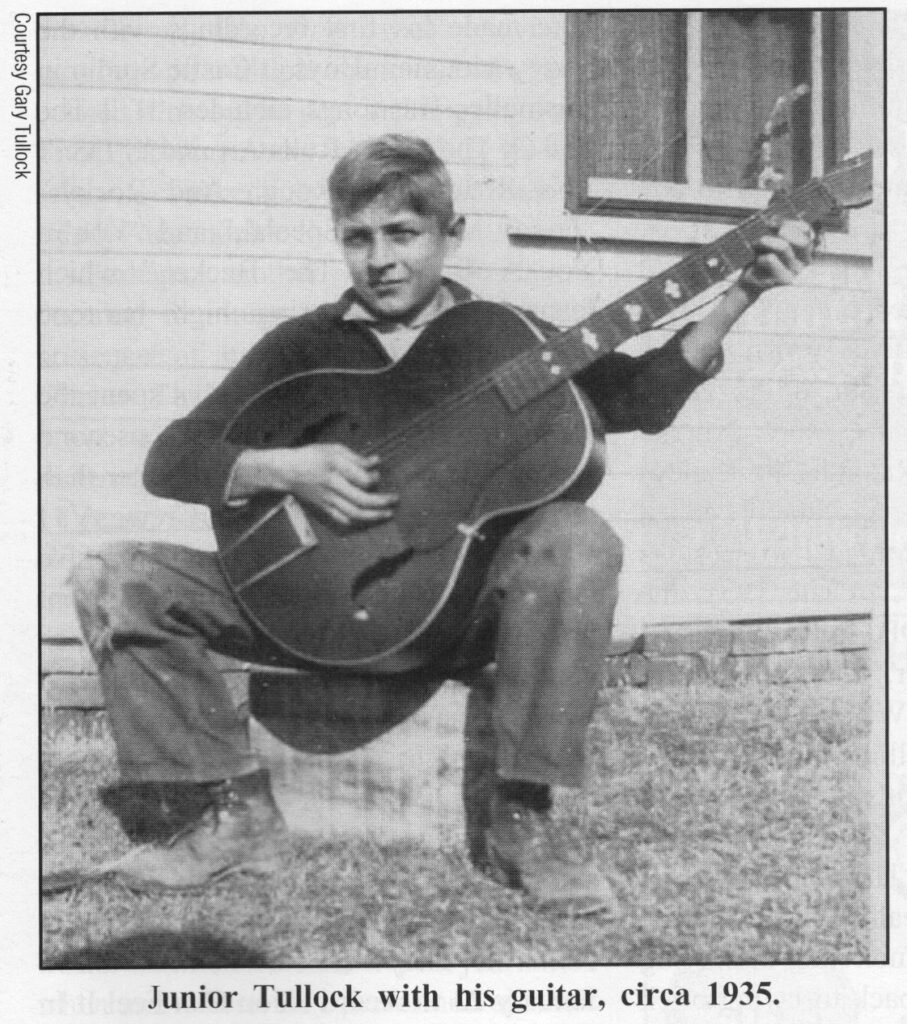

English P. Tullock, Jr., known to his family as “Junior” or “June Bug,” was born on July 23, 1922, in the tiny east Tennessee railroad town of Etowah, about halfway between Chattanooga and Knoxville. He was one of nine children (five girls and four boys, one of whom died in infancy) born to Grace and English Pierce Tullock. E.P. Tullock, Sr., made his living working for the railroad, but, in his spare time, he enjoyed writing hymns. He even had several of his compositions published. The Tullock siblings grew up singing in church and, as teenagers. Junior and three of his sisters formed a gospel quartet. Junior, who had a natural ear for music, was already proficient on guitar and provided accompaniment for their singing. The group was in great demand and performed locally at churches and a few community gatherings.

When he was 16 or 17, Junior moved to Knoxville to live with his aunt and uncle, Carrie and Sam Tullock. By this time, Knoxville’s burgeoning hillbilly music scene was attracting many young musicians. In 1935, announcer Lowell Blanchard had arrived at WNOX radio, and he soon created two highly successful programs: the Mid-Day Merry-Go-Round, which aired weekdays from 12:15 to 1:45 p.m., and Saturday night’s Tennessee Barn Dance. Both shows were broadcast live from an auditorium in downtown Knoxville. Tullock soon began playing guitar with various groups on these programs and at venues around the area. But his musical career was put on hold in late 1942 when he enlisted in the Army and served in the Philippines and New Guinea during World War II.

After returning from service in 1946, Junior trained to be a bricklayer. Soon after, he met Burkett “Uncle Josh’’ Graves, who was playing guitar and doing comedy with Esco Hankins and the Crazy Tennesseans on WROL in Knoxville. Junior bought a bass, and Josh taught him how to play it and helped him land a job with Hankins. At that time, comedy was an essential part of hillbilly entertainment, and most often the role of comedian fell to the bass player. It was apparently Hankins who first gave Tullock the name “Uncle Jake” and Graves who gave him his first training as a comedian. Josh and Jake worked with Hankins for the next year or so, recording on Hankins’ second King Records session. But times were lean, and Josh and Jake both left Hankins to seek more lucrative employment. Jake worked briefly at Brookside Textile Mill before joining the Bailey Brothers and their Happy Valley Boys at WROL.

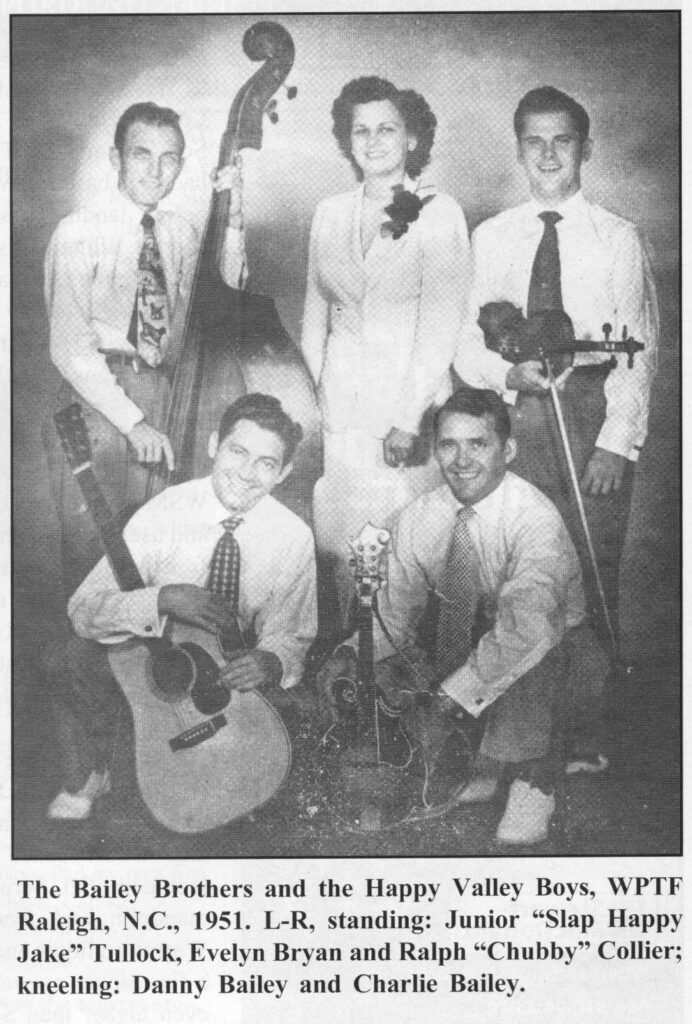

Tullock remained with the Bailey Brothers off and on for about six years. While based at WROL, they recorded two sessions (ten songs) for Rich-R-Tone Records. Bandmembers at that time included Danny Bailey and Carl Butler on guitar, Charlie Bailey on mandolin, Wiley Birchfield on banjo, L.E. White on fiddle, and Tullock, who was now known as “Slap Happy Jake,” on bass.

In January of 1949, the group moved to WPTF in Raleigh, N.C. Jake’s son Gary, who was born in Raleigh, related the story his parents told him about the trip. “Mom and Dad got married on December 31st of ‘48 and the next morning, they left for Raleigh. They shared a car with Carl and Pearl Butler and Pearl’s brother and his son. They got to Raleigh, and the first night my mother and father stayed together was with Carl and Pearl and them, all in one room.”

In Raleigh, fiddler Tater Tate replaced White, and they added a female singer named Evelyn Bryan. They went through a series of banjo players, including Willis Hogsed, Hoke Jenkins, and Johnnie Whisnant. While in Raleigh, the Baileys started their own record label called Canary, and they recorded two sessions (six songs) at WPTF. In late 1951, the Baileys moved to WDBJ in Roanoke, Va. A few months later, they moved to WWVA in Wheeling, W.Va. Gary Tullock recalls his mother telling him that they moved briefly to Pittsburgh with the Baileys sometime in the early ’50s as well. However, by late 1953, Danny Bailey was having health issues, and the Baileys returned to Knoxville, dissolving the band. Jake went back to laying brick and picked up music jobs locally when he could.

By early 1954, Jake was working with Don Gibson on the Mid-Day Merry-Go- Round and Tennessee Barn Dance shows at WNOX. It was there that he first met Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs. Flatt, Scruggs, and the Foggy Mountain Boys had been based at WNOX in 1952 and ’53, before landing a sponsorship deal with Martha White Mills and moving to WSM in Nashville. At that time, having regular work on a Saturday night barn dance show was crucial to a band’s success, and Flatt and Scruggs had their sights set on the Grand Ole Opry. However, their former boss Bill Monroe, who had joined the Opry in 1939, viewed their arrival back at WSM as an encroachment on his territory and used his influence to prevent the Opry from admitting them. After almost a year in Nashville with a daily early morning radio program, but no Opry membership on the horizon, Lester and Earl decided to return to the Tennessee Barn Dance in Knoxville.

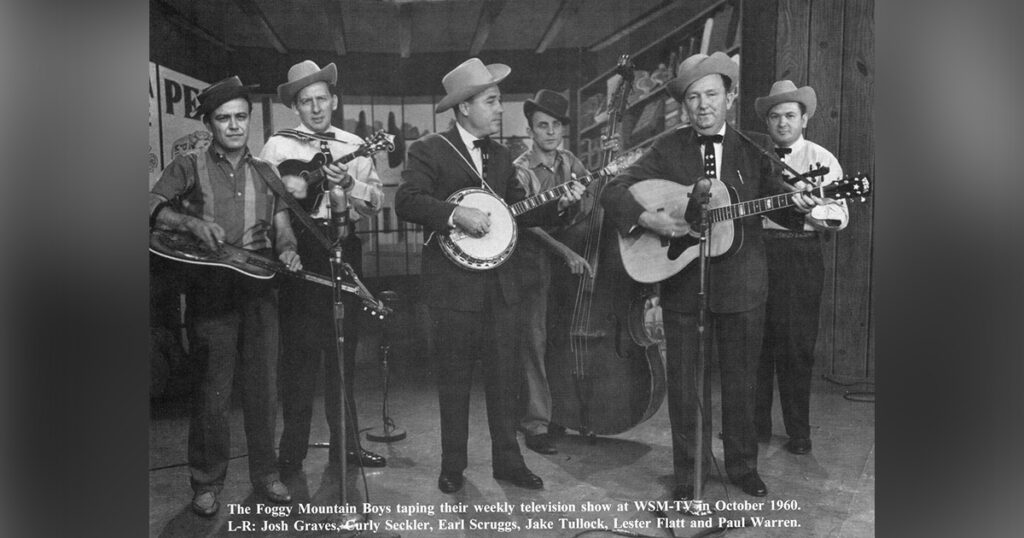

And so, in the spring of 1954, they crossed paths with Jake Tullock and hired him as their bassist and comedian, dubbing him “Cousin Jake.” The band at that time included Flatt, Scruggs, Curly Seckler on mandolin and tenor vocals, and Paul Warren on fiddle and bass vocals. Jake was a fine singer as well, with a vocal range even higher than Seckler’s. On May 19, Jake made his first recordings with the Foggy Mountain Boys at Castle Studio in Nashville. The songs included “Till The End Of The World Rolls Around,” “Don’t This Road Look Rough And Rocky,” “Foggy Mountain Special,” and “You’re Not A Drop In The Bucket,” which featured Jake’s soaring high baritone vocal harmony.

The Foggy Mountain Boys spent the summer in Knoxville where Jake’s second son, Dean, was born on July 6. After that, the band moved to WSVS in Crewe, Va., where they had daily programs and also taped their Martha White shows and sent them to WSM for broadcast. They also appeared on the Old Dominion Barn Dance on WRVA in Richmond every Saturday night. In September, they spent two weeks in New York with the Barn Dance cast, performing on Broadway in a show called Hayride. In January of 1955, the Foggy Mountain Boys moved back to Nashville. They were back in the studio on January 23 to record “You Can Feel It In Your Soul,” “Old Fashioned Preacher,” “Before I Met You,” and “I’m Gonna Sleep With One Eye Open.” Soon after, they began a series of live television programs sponsored by Martha White. In addition to their 5:45 a.m. weekday radio show on WSM, they had programs on Sunday mornings and Saturday afternoons.

Things were going well for the band, but Jake had begun to have health issues. According to Gary Tullock, “He’d had malaria during the second World War, and he had some sort of flare-up of that. He felt like being on the road, all the late nights, was part of the problem, so he quit and moved back to Knoxville.” Jake returned to his bricklaying job and also worked some locally with Danny Bailey, the Bailey Brothers, and others.

Meanwhile, Flatt & Scruggs went through a series of bass players, including Josh Graves (who switched to playing Dobro after just a few weeks), Onie Wheeler, and Hylo Brown. When Martha White Mills decided to sponsor Hylo Brown with his own band in late 1957, the Foggy Mountain Boys once again needed a bass player, and Earl Scruggs called Tullock. Jake refused the job offer, opting to stay close to home, but Knoxville was having a chilly, damp winter, and bricklaying jobs were scarce. In early 1958, Scruggs called again and, this time, Tullock accepted. By now, Flatt & Scruggs were full-fledged members of the Grand Ole Opry with television programs in multiple markets and a jam- packed itinerary of personal appearances. Their bandmembers received a weekly salary, so Jake knew he could make a steady, dependable living.

Perhaps another factor in Jake’s decision to return to the band was the presence of his long-time friend Josh Graves. Their on-stage chemistry would prove to be a popular element of the Flatt & Scruggs stage and TV shows for the next 11 years. Josh and Jake dressed in similar clothes and hats and would sing a song or two together and do their comedy routines with Josh usually playing the straight man. Sometimes, Curly Seckler would be enlisted to sing a trio with them or to be the object of their humor.

Josh and Jake had plenty of time to work out their routines during the long bus rides between tour dates. In his memoir, Bluegrass Bluesman, Josh Graves recalled that he and Jake kept a journal of when and where they performed all their comedy skits in order to make sure they didn’t repeat a routine in the same venue. “[Jake] was one of the great minds for comedy I’ve ever seen,” Josh said. “His timing was perfect. And he was the same way in real life.”

Gary Tullock agreed, “Dad had this twisted sense of humor, and he could find the funny angle on a lot of things. He was funnier by accident than most people are on purpose. He just had a way of delivering a line. The main thing—Dad talked about this—is that everything they did was clean. There was not an innuendo of any kind. It was just Dad as the buffoon.”

Josh and Jake would play pranks on the other bandmembers off the stage as well. Once they put salt in Lester’s bunk. Another time, Jake provoked Lester backstage before a concert, and Lester grabbed a broom and came after him. Jake ran around a comer and Lester followed him, ready to swat him with the broom, but instead narrowly missed hitting the concert promoter.

Perhaps the most devious prank of all was one that Jake conceived and kept secret even from Josh. “They were getting ready to tape the TV shows one day and Dad was in the dressing room, and there was a stack of postcard-sized pictures of Bozo the Clown,” Gary said. The cards were extras from a promotion the station was doing, and Jake asked the producer if he could take some of them. “Then one day,” Gary continued, “Lester opens up his guitar case and there, woven into the strings of the guitar, was a picture of Bozo. Lester said, ‘What is this about?’ Everybody claimed ignorance. A couple of weeks later, Lester opens his guitar case, and there’s Bozo again. And then Bozo started showing up in unusual places.” First, Lester discovered a Bozo card in his coat pocket; then there was one taped to the inside of the curtain at the Opry. Then Jake enlisted the help of Mike Longworth of Martin Guitars, who was leaving on a business trip to South Africa. A few weeks later, an envelope arrived addressed to Lester from Johannesburg with nothing inside but a Bozo card, only adding to Lester’s consternation.

“This went on for about two years,” Gary laughed. “And he would go weeks and weeks, and Lester would think it was over. Then he’d pull back the sheet on his bunk and there would be Bozo!” Jake always kept a few of the Bozo cards in a little black case he carried, along with his comedy journals, extra bass strings, and accessories. One night, when he was removing his bass from the storage bin under the bus, the case fell out and sprung open, spilling the contents, including the Bozo cards. Lester was standing close by, saw the cards, and said, “I knew it was you all along! When this show’s over, you’re going to answer for this!” All through the concert, Jake worried about losing his job, but Lester never mentioned it again.

Beyond their comedic skills, Josh and Jake were talented musicians and singers. In 1962, Gene Williams, a disc jockey from West Memphis, Ark., who had promoted Flatt & Scruggs shows in the area, approached them about recording some of their trademark songs and instrumentals. Earlier that year, Williams had founded a weekly barn dance called the Cotton Town Jubilee that was broadcast live on KWAM in Memphis. By spring, he’d started a record label with the same name. Jake and Josh were both ready to accept Williams’ offer, but Flatt & Scruggs had a policy of prohibiting their bandmembers from recording solo projects. As Jake explained it to Gary, “Lester and Earl didn’t want to give away their sound. They paid [bandmembers] a straight salary, so they felt like they controlled them. And, to be honest,” Gary continued, “That’s the way it ought to be, if you’re on a salary. But they wanted to do this, and Lester and Earl didn’t want them to, so they decided they were going to quit. They turned in their notice, and then I think Lester and Earl sort of thought better of it. Replacing them would have been a pretty big shakeup.”

Jake and Josh recorded the sessions for Cotton Town Jubilee Records later that year. They were accompanied by Curtis McPeake on banjo, Chubby Wise on fiddle, Cedric Rainwater (Howard Watts) on bass, Evelyn Graves (Josh’s wife) on harmony vocals, and guest Pete “Oswald” Kirby on guitar and Dobro. Several singles were released that fall and the album, titled Just Joshin followed in 1963. It included originals (“We’re Gonna Have A Ball,” “Who Was Here,” “You’re Leaving Me”), covers (“Somehow Tonight,” “Right Before My Eyes,” “When You’re Lonely”), Dobro instrumentals (“Just Joshin’,” “Dobro Rumba,” “Oswald’s Chimes”), and novelty tunes such as “Old McDonald’s Farm” (which Jake often performed, complete with sound effects, on Flatt & Scruggs shows). There was no obvious attempt to copy the Flatt and Scruggs sound on these recordings, but with a band composed of five musicians who had passed through the Foggy Mountain Boys at one time or another. There was a marked similarity in style.

Though Jake and Josh often performed material from the album on stage, Lester and Earl would not allow them to sell the records on the road, and distribution was limited. The label was short-lived and only three other LPs were released before it folded in the late 1960s. In 2005, Just Joshin ’ was reissued on CD (with three extra tracks) by Red Clay Records. Dave Freeman’s review in the County Sales newsletter noted, “When this album came out originally, it was a major event in the bluegrass world, as there probably weren’t more than twenty bluegrass albums on the market then and hardly anything that featured the Dobro.” As editor Fred Bartenstein pointed out in Bluegrass Bluesman, the Just Joshin’ album very likely was also the first “solo project” in bluegrass.

Jake and Josh recorded two singles for Nashville-based Spar Records in the mid-1960s: “Swingingest Thing In Town” b/w “Goin’ Nowhere (But Out Of My Mind)” and “Great Big Woman” b/w “Nervous Breakdown.” These were more elaborate productions, and actually received some airplay regionally on country stations. “Great Big Woman,” written by Graves, Tullock, and Jake Lambert, was recorded twice by Lester Flatt (in 1969 and 1976), and has subsequently been covered by several other bands.

In 1962, Curly Seckler left the Foggy Mountain Boys. Over the next few years, Flatt & Scruggs used various tenor vocalists, including Monroe Fields, Billy Powers, Earl Taylor, and Josh Graves, but by the late ’60s, Jake had taken over all of the high harmony singing. As a vocalist, Jake was equally comfortable belting out high harmony parts or trading his bass for a guitar and singing a solo. His voice was unmistakable; emphatic, soaring, and razor sharp. As a bass player, Gary explained, “His thing was to establish a solid rhythm that the rest of the ensemble could play around. He’d tune that E string slack, so he could make a slapping noise with it. He did this bass lick that he called a ‘triple slap.’ It involved hitting the back of his band on the fretboard, and he used that slapping to augment the rhythm. He said the only other bass player that played it was Joe Zinkan.” Jake used this lick especially effectively when he and Earl Scruggs would perform unaccompanied bass and banjo instrumentals such as “Little Darlin’ Pal Of Mine” and “You Can’t Stop Me From Dreaming.”

Over his dozen years with the Foggy Mountain Boys, Jake played bass and/or sang harmony on a total of about 230 recordings. He was with Flatt & Scruggs for many of their career highlights, including performances at Carnegie Hall, the Newport Folk Festival, the 1969 Presidential Inauguration Parade, and various network television programs, as well as recording the soundtrack to the movie Bonnie And Clyde.

In early 1969, Flatt & Scruggs broke up, and Lester Flatt took Jake, Josh, and Paul Warren with him to form the Nashville Grass. They returned to performing the traditional material that had proved successful for the Foggy Mountain Boys, while Earl Scruggs branched off into more modern sounds with his sons. As he had with Flatt & Scruggs, Jake continued to provide the solid bass work, high baritone harmonies, novelty songs, and comedy with Josh. However, in May of 1970, Jake suffered a heart attack and spent several months off the road recovering. He returned to the band for about ten months, but decided his heart was not healthy enough for life on the road. Jake made his last recordings with the Nashville Grass in March of 1971. That summer, he left the band, sold his bass, and moved back to Etowah, where he took a job as overnight dispatcher for the police department.

However, Jake did not leave music behind. He made several guest appearances at bluegrass festivals, including Lester Flatt’s Mount Pilot Festival, and a Foggy Mountain Boys reunion at Camp Springs, N.C., in 1983. He recorded two albums with the Bailey Brothers in the mid-’70s for Rounder Records. He performed on a few shows with Josh Graves and Kenny Baker in the late ’70s. He participated in various fundraising events in Etowah. He also helped to start a Saturday night music series called the Starr Mountain Jamboree, at Etowah’s Gem Theater. Prior to this, the Gem had been closed for years, but thanks to the success of the Jamboree, the town was able to secure grant money for renovations, and the theater is still operational today.

After years of declining health, Jake Tullock passed away at age 65 on June 18, 1988. His beloved hometown now pays tribute to him through the annual Cousin Jake Memorial Bluegrass Festival, which takes place at the Gem Theater in early March. The one-day festival launched in 1994 and is presented by the Etowah Arts Commission. It features both local and nationally known bands. The list of acts that have performed there over its 21 -year history includes Earl Scruggs, Little Roy and Lizzy, Kenny & Amanda Smith, Larry Cordle and Lonesome Standard Time, and The Boxcars.

Gary Tullock has no doubt that his dad would have continued his musical career for many years, had it not been for his health issues. “He loved entertaining people,” Gary said. “Dad was good enough to have gotten off the road and just been a studio musician. He had an opportunity to travel in some different circles of music. A couple of [country] acts tried to hire Dad. He chose to stay with bluegrass, chose to continue to do the kind of music that the people liked. But the people that liked it also liked his humor. He told me many times, ‘I just love to make people laugh.’ He did it as long as he could.”

Though he left us too soon, those who never had the opportunity to see Cousin Jake Tullock in action can now enjoy his many talents on the ten volumes of The Best Of The Flatt & Scruggs TV Show that were released on DVD between 2007 and 2010 by Shanachie Entertainment and the Country Music Foundation.

Penny Parsons has worked in the bluegrass industry for 35 years in various capacities. She coauthored The Bluegrass Music Cookbook in 1997 and is currently working on a biography of Curly Seckler.

Share this article

6 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Cousin Jake is my favorite F&S backup singer. I loved his high tenor, his bass playing, and his comedy routines. He is a guy I would have loved to meet and spend some time just talking about his musical experiences. Thank you for this article. It was a great read, and a way to get close to Cousin Jake.

I met Jake around 1954. I was a teen on my bicycle and as I approached a stop sign at an intersection in Siler City, a lean fellow jumped out of a car that had stopped at the intersection. He was waving his arms and asking directions to the school house. The car was a lettered, stretch limo with a canvess covered bass fiddle on top. I told Jake to follow me. The limo followed my bike to the school house. I knew that the cafeteria door was never locked. It was easy access to the stage from there. I knew who it was because I also was playing music by then and was planning on going to see Flatt and Scruggs that night. I did go and really enjoyed it. It was Flatt, Scruggs, Curly, Jake, Josh, and Paul Warren.

Thank you for reprinting this fascinating and informative biographical account of this dedicated Bluegrass icon!

Saturday March 1, 2025 3pm pst. Such a beautiful gentle soul was Mr. E.P.”Cousin Jake” Tullock, kinda reminds me of my son Izzy. When a person has a strong character enough that so much joy emanates from the way they interact with people, you know God blessed the world with an example of how we all should live among each other, with kindness, happiness and tradition. I never knew Cousin Jake, but I sure knew his TV personality enough to say I sue like and respect that fella. A veteran, a survivor, a parent that was greatly loved by family first, friends second and those fortunate to learn and know of him was Cousin Jake. He will forever be remembered so long as Bluegrass lives. RIP Cousin Jake. Gil Lopez of Anaheim, CA

“Cousin Jake Tullock” was my actual Cousin ! I had the pleasure of meeting him at a family reunion one Sunday, in my Parents Hometown of Etowah, TN.

At the time I was pursuing a Singing career in Country Music, and Jake and I were discussing the Music Industry over a Sunday afternoon lunch with my Parents,when across the lunchroom, two elderly ladies were looking at us,and said would you look at those Two (meaning Jake and I), Jake and I looked at each other and it dawned on us , we were each wearing a Yellow Shirt,Black Pants, Black Boots and then I looked out the window at Jake’s Car, it was a Black Oldsmobile Cutlass! I had also owned several Oldsmobile Cutlasses!

Jake and I just laughed at the discovery! You see, Jake and I were actually DOUBLE 2nd COUSINS ! His Father and my Grandfather were Brothers and the Married Sisters ! There is a fine Example of DNA at Work !

My Father grew up with Jake in Etowah and was his 1st Cousin and also like Jake was a Very Good Guitar Player and also as a teenager played on the Radio !

I also play Guitar and Sing, And my Oldest son is a Great Guitar Player and he and his younger Brother, Own and Operate A Chain of Music Schools in both the Seattle and Dallas areas named 4/4 School of Music. It’s in the DNA Folks !

Sincerely

Dennis R. Tullock

P.s Jake Was a Very Kind and Talented Gentleman!

Very Proud of my “Cousin Jake Tullock” !

Yes from the very first moment I say the great Jake Tullock playing with F/S I loved this guy. He’s beyond a super bass player and omg is this guy funny best timing ever. I’d be attending Jake Tullock celebration but with head injuries with symptoms exact like Alan Jackson sadly not sure that will ever happen in my life. That guy makes so very happy can’t express in words how I just love heck outs this great man. Really connection came when I discovered he was in exact same WW2 battles at my Pops Paul N. Horton. Sadly battling pneumonia at moment. But watch the great Cousin Jake Tullock inspire me fight this pneumonia. Bless the great man he is. Love ya. Thank you.