Home > Articles > The Archives > Lester Flatt Memories

Lester Flatt Memories

With interview by Curly Seckler

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

May 1986, Volume 20, Number 11

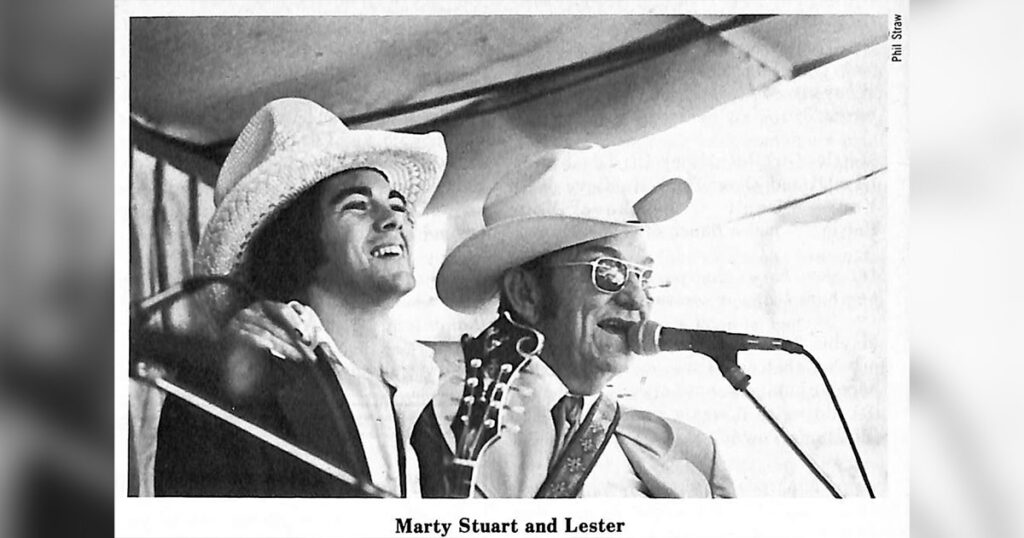

It’s a worn out cliche, but sometimes I think that the phrase, ‘‘There was only one of him. And after he was made they threw away the mold,” was invented for Lester personally.

His very presence of that laid back, don’t worry about it casualness made him a study in motion animating one scene after another with the seemingly effortless charm of just being himself. In short, Lester had a style, and it was tradition.

You remember his music, his voice, the way his guitar hung when he talked, the way his hands looked when he played, the hat, how he M.C.’d the show and the sincerity of it all. But Lester’s conversation was the key to his whole character. He held on to the appalachian dialect from his youth and used its slang at the service station or the White House, he never changed it for anyone. Lester let most of the ways of the world come around to find him. He moved at his own pace.

For example, the time his booking agent called and advised him if he would change this and change that that he would be on the road half as much and pretty much double the money he was earning. Lester told him he was doing fine and we carried on at the same pace playing little schools and places where he had been a number of times before. Some of Lester’s decisions left people in Nashville scratching their heads but he didn’t have to be on the road in the first place, but it was his way of life and he enjoyed it. He was once asked why did he not try and work the larger halls anymore. His reply was simple, “I enjoy the smaller places now because it gives us a chance to lie around our kind of people.”

As he slates in this interview, he never was a publicity hog. And that’s the truth! It wasn’t the easiest thing for a writer to fish Lester out for an interview. But when he did talk, whether in general or giving his views on a particular matter to a reporter or at the coffee table; he turned it into a comfortable boardroom. His words were important.

He had worlds of fun about him, but when he leaned into serious talking, his manner was assured and direct. I never found his prophecies wordy or elaborate, just plain earthy sense that anyone could live by.

Curly Seckler took his recorder and spent a while talking to Lester mostly having the old bluegrass story told in part once again, and occasionally swapping a tale from the road. It was to be Lester’s last interview.

If you knew Lester, you well know that for each question answered here, there’s a hundred more stories to go along with them, and it’s nice to hear Flatt and Seck talk it over one more time. Much obliged!

What about that guitar lick you’ve got? I’ve heard you call it a “scissor G”.

Well, a scissor G is what I call when you make a G chord with your thumb and your middle finger. But this little run that I make, I didn’t think anything about it when I was using it. Actually, we were doing everything so fast that we needed to have a time-setter to come back in on. And that was actually what I was using it for—more than anything else. We started out like [the speed of] next week and there was a lot of live bands on stations about anywhere you wanted to tune them in, and it seemed like you could hear them all doing it.

Yeah. Now that lick [Lester’s style of the G run] that you are speaking of. You were the first person to bring that to the Grand Ole Opry.

Right.

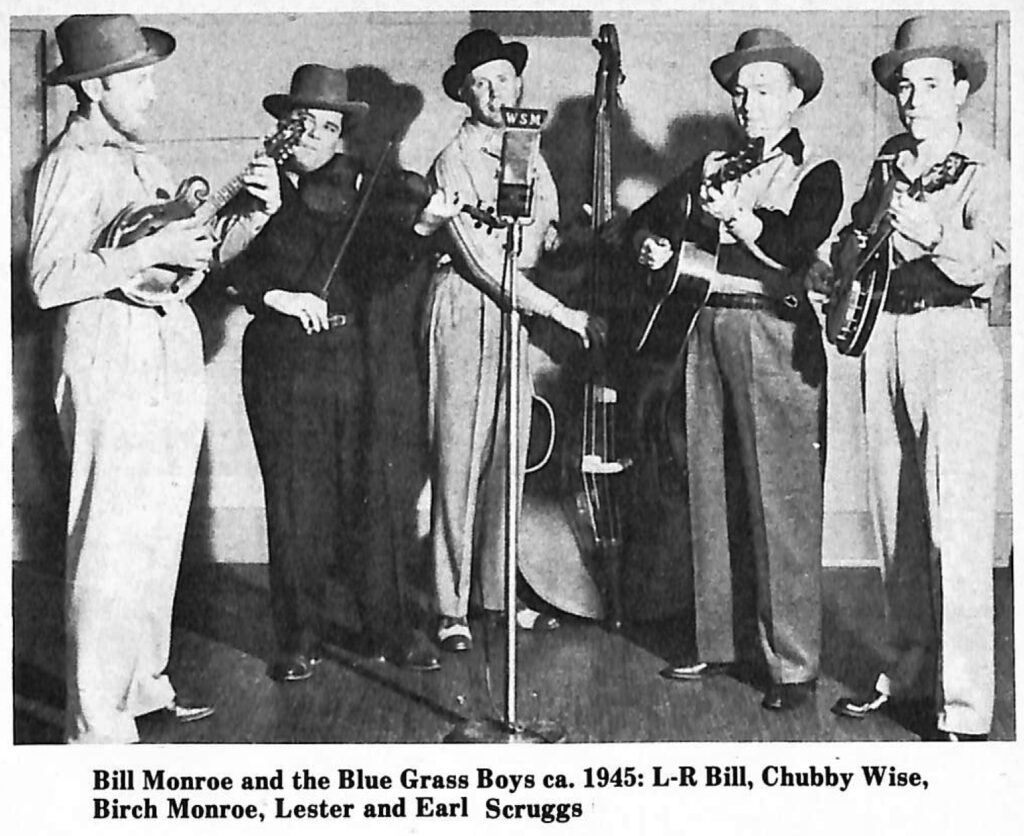

And that was when you joined Bill Monroe in 1944?

That’s correct.

You brought a sound into Bill Monroe’s outfit that nobody else had ever heard on the guitar.

I believe that’s right. I had never heard it. I just lucked into it I guess. I just played what I felt.

You wrote so many good songs. Did you write these before you worked with Bill?

I wrote “Will You Be Loving Another Man” before I joined Bill. I believe that was one of the first ones we did. After that I wrote “Sweetheart You Done Me Wrong,” “How Would You Like Being Lonesome [Will You Be Lonseome, Too?]” That’s three that I can recall that me and him did.

When you were with Bill, his group had a five-string banjo, but it was a different style than you hear today, right?

Well it was Stringbean, and he played what we call a drop thumb style.

And that went on for how long before the “Shelby, North Carolina Flash” came in?

Well, I wouldn’t want to say just exactly how long but it was several months and I know as good as we all loved String, and I love that kind of banjo picking because I was raised on it. My daddy played that style and I tried to learn it and I couldn’t; that’s how come I quit fooling with a banjo. Bill told me one night after String had gone, that he was trying out a new boy on the banjo. I hated to hear that because I was really enjoying the work that we was doing with a banjo. Poor old String, it just didn’t fit. He would really drag you [down] on that thumb string on those tunes like we’re doing today.

What was it that you said when Bill said there was a fellow outside that was there to tryout for a job? (Laughter)

I’ll never forget it. When he said that, I told him as far as I was concerned, he could leave it in the case.

Now when you did listen to him, tell us a little about what you thought.

Well I was thrilled. It was so different. I had never heard that kind of banjo picking. We had been limited, but Earl made all the difference in the world.

Uncle Dave Macon was there at that time. What was it you told me one time that his opinion was of Earl? (Laughter)

Well, when he got his banjo out to do a little auditioning for Bill everybody was ganged around listening just like myself, because it was entertaining. And Uncle Dave was standing over there with that gold tooth a-shining, and he listened for a while and he said “Aaahh. Sound’s pretty good in a band,” —there was two or three playing with him you know he said, “I’ll bet he can’t sing worth a damn.”

Now I know when you come to work with Bill you brought a different sound in. But when Scruggs came in he really brought something different in.

It was all together different, yeah, it sure was.

Now you two fellows, Flatt and Scruggs, worked with Bill for how long?

Well I came in the latter part of ’44, and Scruggs came in ’45. We worked with him till ’48, then we left and organized the Foggy Mountain Boys.

Now after you got going and when Flatt and Scruggs came back to the Grand Ole Opry, you were playing bluegrass but mas it a different style of bluegrass than the Blue Grass Boys were playing? You and Earl really changed a lot about the music wouldn’t you say?

I would have to say, yes. Because Bill had an accordian in his outfit at that time and String was playing dropthumb and Andy Boyette from Miami was playing bass and he would drop back and feature some tunes on the electric straight guitar.

You really changed things because I was in China Grove [North Carolina] listening with one good ear. And people were talking about the change in Bill’s sound. When you left Bill you kept your same sound.

Yeah, we had a good outfit. It wasn’t too long until we got a chance at some network stuff. At the time our type music was more or less limited to the South. And the people up in the New England states and some of the Northern states started talking about the “new” sound of Flatt and Scruggs, and we’d been playing it here for years.

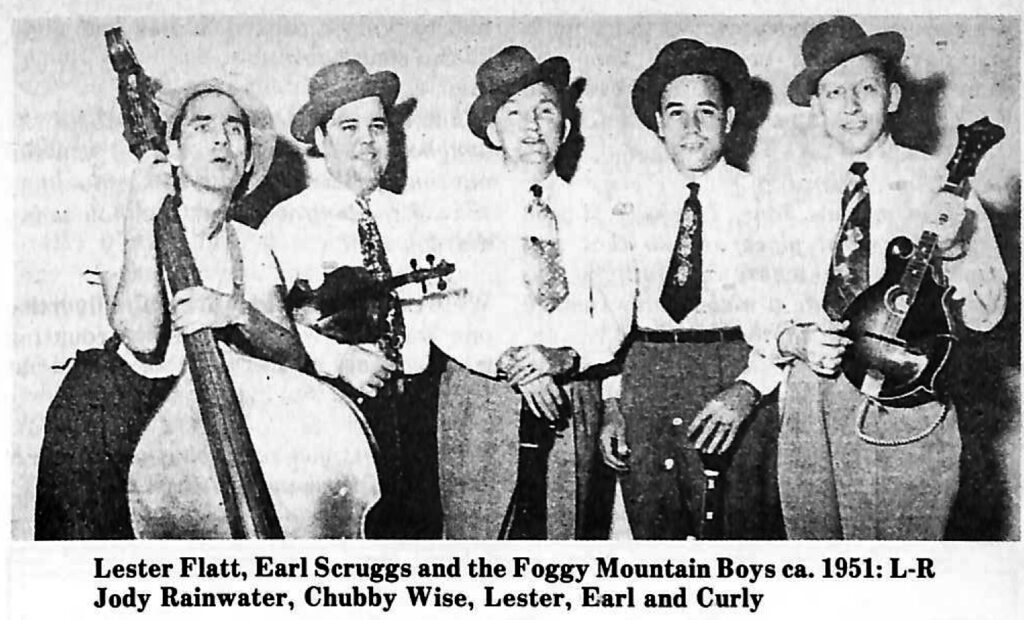

Now when you and Scruggs first organized the ‘Foggys’ where were you located?

We messed around up in Virginia for a few days getting organized, then we came on down to Bristol, Tennessee to WCYB —it was a powerful station.

You told me one time, I believe it was maybe the first place or two that you played was somewhere in Kentucky and that a fellow rode a mule about twenty miles to see the show that night.

He had one hooked up to a rail out there. And he said that he had rode him twenty miles. You don’t know what you’re gonna do when you’re first starting out, but we had to do two packed houses that night at the courthouse.

What was that deal at WCYB about the songbook? They would only let you run one on the air for a certain amount of time. How long was that, and how many did you sell?

Well they would only let you advertise one for four weeks. And not counting what we sold on the road, we mailed out 10,000 books.

What was it you said about me the first time you ever saw me? (Laughter)

Well I’ll never forget that… We were playing a show over there in Carolina. Before showtime, I saw you coming down the hill in a stretched out Packard, and you came on over and we got to talking to you. On the way back somebody mentioned you and I said, “I believe there goes a little bit of a smart aleck right there.”

I was thinking that was what you said.

Well you always draw an opinion of a fellow whether it’s good or bad.

Well finally I came to Bristol and talked to you about a job and told you if we could ever get together and do some singing that I would like to. One day you called me while I was in Augusta, Georgia working with Jim and Jesse, and I came on up there and went to work with you and Earl. Did that change the sound of the Foggy Mountain Boys when I came to work?

Yeah, your mandolin playing! (Laughter) No, you certainly did, there’s nobody in the business Curly, that’s got a sound in tenor like you.

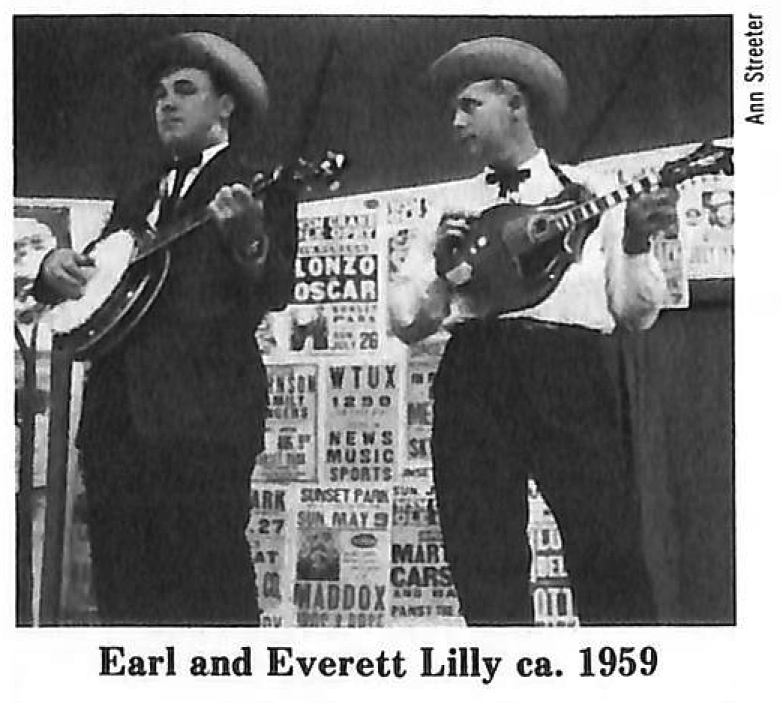

Thank you, Lester. I appreciate that. You know I was there for a few years then I left and Everett Lilly came to work and I think that he sang some fine tenor on the numbers that you were doing.

Everett was a fine tenor singer, but he didn’t match me like you did.

Lester, back in the early fifties on the average, how many numbers were you writing a week?

From three to five.

You wrote a lot of gospel numbers. What are some of the titles?

It’s hard to remember. I’ll mention “God Loves His Children,” “I’m Going To Make Heaven My Home,” “I’m Working On A Road To Gloryland,” “Be Ready For Tomorrow May Never Come.”

What are some other numbers that you wrote?

“Little Girl [of Mine] In Tennessee,” “[I’m] Head Over Heels In Love With You,” “Don’t Get Above Your Raisin’” — just a bunch of them.

Do you have any particular favorite numbers that you wrote or did?

Maybe “Cabin On The Hill” and, a number that never was one of our more popular numbers, but I always liked even if I did write it was a song called “The Old Home Town.”

And I have to thank you for helping me on a song that I brought to you that wasn’t completed and you helped me finish called, “No Mother Or Dad.” It seems like you can’t go to a festival without hearing at least eight or ten of your songs. They are sort of like an oak tree, they seem to just keep on growing.

Well that makes me feel good when you hear people singing your songs. A lot of them are standards today.

What is your opinion of bluegrass festivals? Do you think that they will continue on?

The good ones will. A few you can count on to stay around. But there’s going to be a lot of them that are going to go. You’re going to have to keep a good festival and something that the people can take their family out to, or they are not going to be there too many times.

You were the first man to call a Dobro a “hound dog” weren’t you?

Yes, I guess I was. As far as I know I am.

Back in 1955 when Josh Graves came to work with the ‘Foggys’ he didn’t come in as a Dobro player did he?

No, we hired him as a bass player and to do a little comedy. We got to running him in for a tune on the “hound dog” and it sounded so good that we went on and switched him to the “hound dog” altogether. A few people criticized us for doing it, but now they would criticize us if we left it off.

Around the late fifties you and Earl were the only band around that was using a “hound dog.”

Yeah, even Acuff had Oz playing I believe an electric type Dobro or steel, and he had Shot Jackson playing steel. And I’ll tell you something else; a fiddle was so dead, you couldn’t give a fiddle away. Nobody seemed interested in a fiddle. I was more or less raised on a fiddle and a banjo, and I would still keep throwing a fiddle tune in on every show. Now today it’s a different story. A fiddle is one of the hottest instruments going around a festival or in the colleges.

Count the little mandolin in too. Do you remember what Josh told me about that? (Laughter)

Yeah, you come in the bus one day and set your mandolin down, and made the remark: “A mandolin was about as dead as Hank Williams,” and Josh slipped up behind you and said, “Yeah, and you’ve done about as much as anybody to help kill it.” (Laughter)

Just as I remarked about your songs earlier that they keep on growing and getting bigger, you seem to be doing the same thing in colleges. Sometimes, I’ve noticed three or four guards having to get you through a crowd after a show.

Well, that makes us feel mighty good. When we get a response like that it makes us feel like our work hasn’t been in vain.

Lester, I would like to see you voted into the Hall of Fame as the King of Bluegrass Music. You may not care anything about that, but I would like to see that happen for you one of these days.

Well I’ve always appreciated anything that came my way, but I think you know me well enough to know that I never have been a hog about publicity.

Your association with Martha White has been for a long time. I’ve wondered if it is one of the longest radio shows and sponsors connected with WSM?

They were doing morning shows before we came in, and we’ve done it “forever.” Since ’53 I believe. I’d say it would have to be a record for any one sponsor, especially in the South.

When television came along, you and Scruggs started doing that as well as radio, but you did all of the shows in different towns and they were live, right?

Right. They didn’t have video tape then. So we had to travel to do them. We rode 2,500 miles each week doing six television shows. Plus we would play a personal appearance at night somewhere in the radius of the television station.

And, it didn’t take long for you all to catch on anywhere you went. You sold a lot of songbooks off of those stations. How many was it that you sold the first time you advertised in Huntington, West Virginia?

A little over 1,400. We went into that place cold. No advertisement saying that we were coming. On the first TV program we did, I briefly mentioned that we had a songbook that would be off of the press the next week, and if you wanted to be one of the first ones to get one, then send however much it was at the time. When we went back the next week to do the show there was over 1,400 orders waiting.

How long did that 2,500 miles a week last?

I believe about two years. Then videotape came along, and we danced a little jig because then we could tape them here in Nashville send them out to the stations.

What is your favorite sport?

What? (Laughter)

I believe I’ve seen you with a fishing pole in your hands.

That’s what I love, fishing and hunting.

•

In other words, if I were to call you tomorrow evening to go to a football game, you might not be available?

Right. I might be fishing.

What was it that you told the doctor after your open heart surgery when he told you that you needed to either walk or jog one to three miles a day?

I told him that I sure would —in my car.

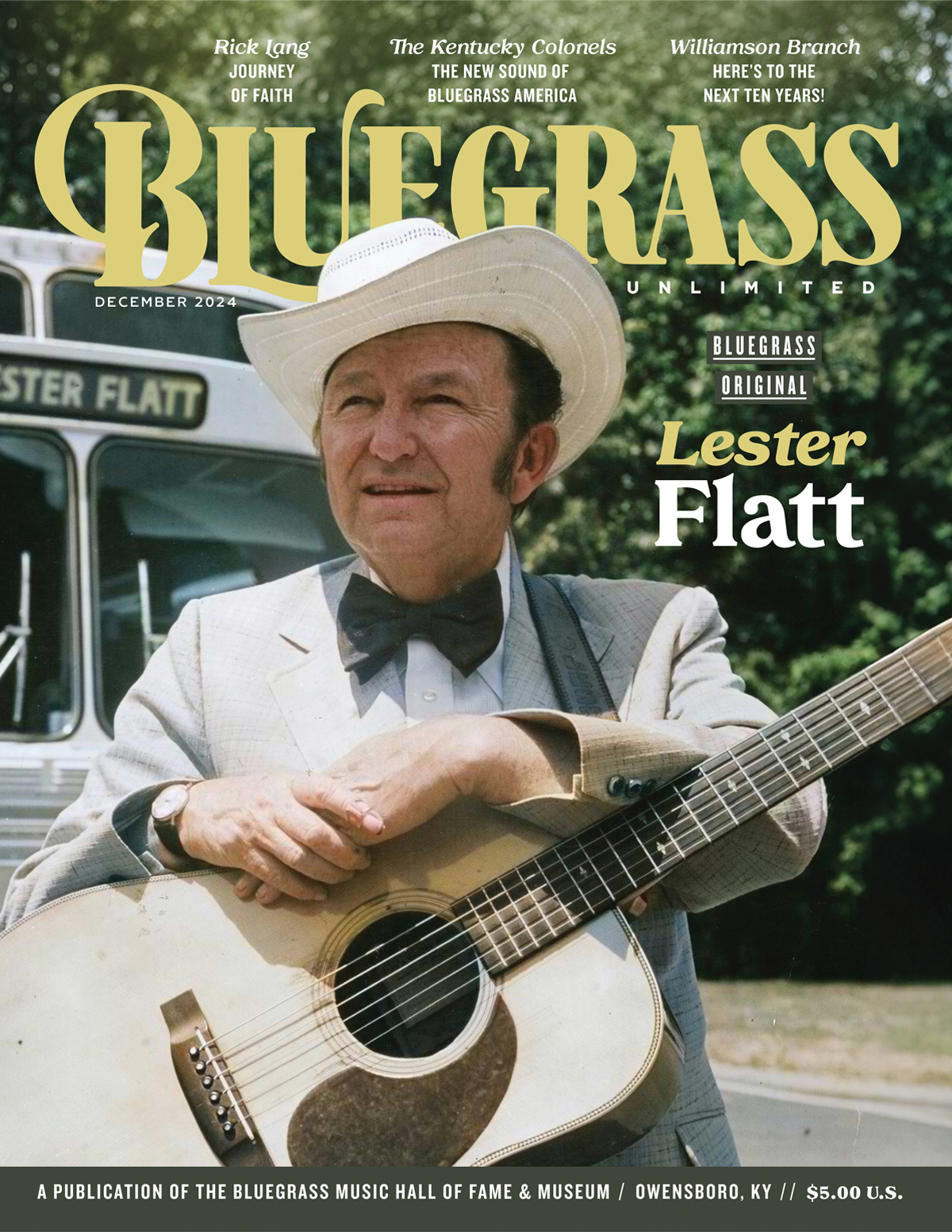

Lester, you’ve always worn a hat. That has always been a big trademark with you down through the years, hasn’t it?

I suppose so.

What was it that the announcer used to say about you?

He’d always put me on by saying, “Here’s the man with the hat, Lester Flatt.”

I’ll never forget it. When he said that, I

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Hello,

thank you very much for last issue with Lester Flatt. And for the archive interview with Curly Seckler; I hoped that right it would be published on the website.

I think that there are a mistake on the end of this interview; with a nearly ended last sentence (“I’ll never forget it. When he said that, I…”). Probably part of next text is missing.

I wish you a Marry Christmas, Happy New Yer, and I look foreard to other nice hours with Bluegrass Unlimited.

Yours

Martin Cechura, Pilsen, Czech republic