Home > Articles > The Archives > Tom Morgan—Best of Both Worlds

Tom Morgan—Best of Both Worlds

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

August 1988, Volume 23, Number 2

If the term “Morgan Thoroughbred” makes you think of horses, and not banjos, then you haven’t met Tom Morgan yet. If you already know that the Thoroughbred banjo is a superb instrument designed and built by Tom and hand-crafted at the Morgan Company, you might not know how that company got started and why. It’s a story about Tom, his mountain heritage, and his wish to pass that gift on to his children, friends, and anyone willing to share it.

For over thirty years, Tom has devoted himself to furthering the development and appreciation of bluegrass music in many areas of the United States, as well as parts of Canada and Europe. As a luthier, he has achieved a reputation as a perfectionist and master in his craft. As a musician, he has shared a stage with the best that bluegrass has to offer, and has built, repaired or customized the instruments many of those musicians play.

I met Tom in 1970, just over a year before his retirement after twenty years in the Air Force. To me, he never seemed at home in the formality of the Washington, D.C. area. When he decided to move, with his wife and three children, back to the family property at Morgan Springs, Tennessee in 1972, it came as no surprise to anyone who knew him. While working at the Pentagon, he ran the rigid paces of military life most of the week, and spent the majority of his remaining time in the basement shop at his home in Takoma Park, Maryland, repairing instruments or visiting and picking with the friends who played them.

I was sixteen then and, frankly, in awe of the man. I watched him work as he precisely measured the distance between frets on a guitar neck or soaked wood to prepare it for shaping into an instrument’s sides.

I asked him countless questions, about seasoning the wood, selecting abalone, and anything else that got my curiosity up. The one question that I didn’t ask until later was: “How did your involvement with luthiery and bluegrass get started?”

To fully understand the answer, I went to where it all began, to Morgan Springs. The worn station wagon bumped up the gravel drive that winds past the Morgan Company shop toward the family home, and I entered a world far different from the one I left behind in New Orleans. A pileated woodpecker pounded its beak into a nearby tree-stump. The run-off from the lake sang its own sparkly tune. The air was fresh and clear.

Again, as in years past, I visited with Tom in his shop—banjo necks and rough-cut mother-of-pearl inlay patterns cluttering the worktables. I looked from sawdust sprinkled floors to Tom, his curly hair speckled with silver. My childish sense of awe was replaced by respect and admiration for a friend who had a dream and the drive to see it to fruition. More than before, the shop had become an extension of the very fiber of his being.

He reached into an old green file cabinet and handed me 50 pages of autobiographical notes. That night, as I lay awake in the stillness of the woods at Morgan Springs, I read of the part Tom played in the early growth of bluegrass and of his single-minded love for that brand of music that he continues to take every opportunity to share today.

The musical tradition in the Morgan family evolved slowly, from casual beginnings during the Civil War, when Tom’s great uncle Bill played bugle and fiddle in Company B, 6th Tennessee Mounted Infantry. Tom’s grandfather, G.W. Morgan, played violin and sang, and G.W.’s wife, Mary Snow Morgan, had the reputation of having one of the finest alto voices in Morgan Springs.

Tom remembers scenes from early childhood that include his father singing tunes like “Free Little Bird” and “Preacher And The Bear.” Also, his mother loved singing hymns and popular parlor songs. He and his three younger brothers enjoyed visits to families nearby who also played the music of the region. Tom fondly recalls the first time he ever heard a song that has become one of the most popular folk hymns.

“I was probably eight years old when we visited the Henry Smith family over on Cumberland Mountain. Every member of the family, from oldest to youngest, either played an instrument or sang along. That’s where I first heard ‘Will The Circle Be Unbroken.’ ”

In the same way that environment and heredity apparently influenced Tom’s later interest in music, those same factors could have affected his ability to excel in woodworking and luthiery.

“My dad was an excellent journeyman carpenter. Woodworking tools were always available … I got an old fiddle all apart and a cracked up Kalamazoo flattop guitar to start tinkering with, mostly with negative results.

Later, as a student at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, he developed a knack for bringing musicians together. His friendships were formed with music as the common bond. He took a few 75 cent banjo lessons from Rick Kavanaugh, learned basic chords on an arch-top Harmony guitar (bought for $14) from another, and finally joined the first band he ever performed with.

“We got a few gigs, like the U.T. Agricultural School party, and started a Saturday night barn dance out on Kingston Pike. The most notable part was that Kennett Smith, our banjo player, showed me a three-finger roll and several chords that I was able to pass on to my brother, Ross. Kennett was from North Carolina and played both clawhammer and Scruggs style. In fact, he was the first three-finger player I ever worked with.”

While at U.T., he also had the opportunity to play bass with Carl and Pearl Butler on the Cas Walker Show. He began to collect, on paper and in his memory, a vast reservoir of old-time tunes and popular country songs.

Besides Ross learning to play 5-string banjo, younger brother Marion became infatuated with an Army & Navy Special Gibson mandolin borrowed from an Aunt, and later took up the fiddle. In turn, Arlen learned to play guitar providing the potential for a 4-piece family string band.

One summer in Chattanooga, in the early ’50s, Tom went to hear Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys play at the American Theater. He also had the opportunity to hear them on the radio, and that “special blend of banjo, mandolin, and fiddle” began to strike a very special chord with him (pun intended). Little did Tom suspect that he and Monroe would someday play together.

During the next few years, Tom’s life took a complete about face. At the outbreak of the Korean War, he left U.T. to join the Air Force. In 1953, he married Mary Newell from Dayton, Tennessee. After several temporary moves, they packed their bags once more, and headed for Washington, D.C.

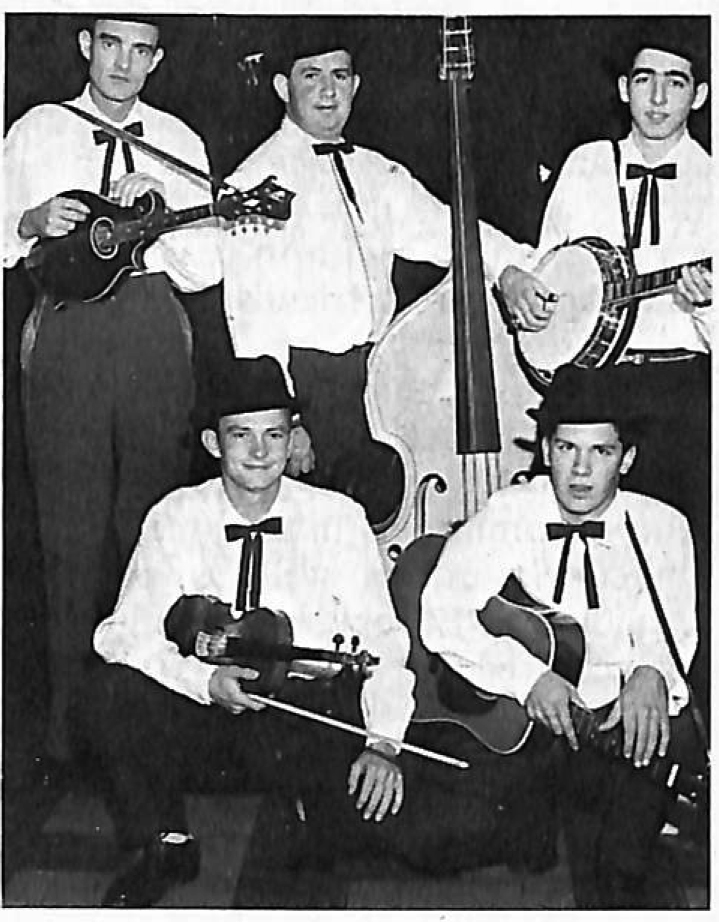

Barely settled in, Tom met Blackie Morgan, who played at square dances in the area. Tom began playing professionally to supplement his Air Force income and because he just loved to do it. He met fifteen-year-old Pete Kuykendall, who was getting a good start on fiddle. Tom and Pete, along with Paul Champion, Harper Kirby and Dan Conner, later replaced by Buddy Davis joined to form the Log Cabin Boys. A later photo of the group shows a slight change in the band’s membership to include Carl Nelson on fiddle, Pete moving to guitar, Jim Selman on mandolin, Tom on bass, and Paul Champion on banjo.

“The band decided to enter the (Warrenton) National Country Music Contest … and dressed in black pants, white shirts with string ties and black derby hats we found at Goodwill. Our attire was probably the most memorable thing we had going, but Paul Champion won second place in the banjo category the first year we entered, probably 1955.”

That same year, Tom and Mary’s first child, Scott, was born. During his early childhood, Scott spent probably as much time around music and instruments as most little boys spend with toy trucks and trains. He remembers trying to play an instrument when he was just barely big enough to hold one. It’s more than likely that he tried before then.

At any rate, with Tom and Mary’s move to D.C., the pebble had been dropped in the water, and now the ripples would start to spread. He and Pete found a Martin 000-45 in a pawn shop in Roslyn, Virginia, which they bought for $62.50 (before very many people really knew or cared what a Pearl Martin was) and traded it to Benny Cain for a brand new D-28. The equality of that trade sounds questionable, but at the time Tom wanted a D-28 more than he wanted a 000-45, so the purpose was served.

He met Callie Veach (See BU, Jan. ’82) around this time, who generously shared with Tom his instrument collecting and repair abilities. Tom has since bought, sold, traded, repaired, customized, or built so many instruments that he lost count long ago. With Callie’s help, he also developed a vast knowledge of the “history and models of good instruments,” and now helps others in the same way that Callie helped him.

At the same time, Tom continued to play bass with various local artists, including Buzz Busby and Bill Harrell, and later on Red Allen and Frank Wakefield and countless others. Reading about Tom’s memories of those times, it seems he was in it as much for fun as for profit: “when Bud Gordon had the band and the bass inside his Cadillac with the roads covered with ice and snow, we stopped in Washington, Pennsylvania, and borrowed a handsaw to cut off enough of the bass peghead so it would fit in the trunk.”

Word spread fast about Tom’s repair abilities, especially in dealing with banjo necks. He first began working with banjo necks when the five-string became popular and people came to him for conversions (from a four-string to a five). A request for a curly maple neck with flying eagle pearl from Fred Weisz in New Jersey put Tom in touch with musicians in the New York bluegrass scene, opening up a whole new territory.

One special friendship that developed during that ‘pioneer’ period was with Mike Longworth who now is the Consumer Relations Manager at Martin Guitar Company. The mutual attraction was fancy Gibson banjos, or more specifically, how to make fancy ones out of plain ones!

Later, customers would request his services from as far away as Scandinavia and the Far East. Katsushiko Usami, of Japan, corresponded with him over the years, and eventually translated a pamphlet Tom wrote, entitled Gibson Banjo Information, into Japanese. Tom assembled a banjo neck for Katsushiko, using color photos to match the sunburst shading of the neck with the hue of the rest of the instrument.

Tom wrote that “being in the Washington, D.C., bluegrass scene in the 1960s was truly being in the right place at the right time.” He was able to play some of the earliest bluegrass festivals with Bill Clifton at Luray, Virginia, participate in field recordings with Mike Seeger, be a part of the Bill Monroe show, play guitar with Larry Richardson in a banjo contest at Warrenton, and carry home a number of trophies from the many Air Force Talent Contests that he entered.

Tom and Mary were also among a small group of Washington area bluegrass devotees who supported efforts in getting a magazine started that would cater solely to the interests of folks like themselves. The endeavors panned out and twenty-three years later you are holding the results.

It’s impossible to mention all those who came in contact with Tom in those early years; who he influenced and who had an equally great affect on him. Suffice it to say they were many, and can’t all be mentioned here.

By the ’60s, Scott had been joined by a younger brother and sister—Rick and Melissa; Mary had begun playing Autoharp, and Tom’s Rolodex file was filling up with names of instrument owners, musicians, sources for wood and abalone, and friends of bluegrass. By 1964, Mary was performing with Tom at occasional club jobs.

Their style of playing was softening, leaning away from hard-core bluegrass and toward a style influenced by the Carter family. Melissa and Rick weren’t as interested in playing as Scott, so Tom, Mary and Scott played as a trio. One Christmas, I tagged along when they performed for the residents of a nearby nursing home. The joy on the faces of that audience was all the reward the Morgans needed. Their desire to perform simply for the pleasure of knowing that they have shared a part of their rich musical heritage, and not for fame or fortune, continues today with their participation in the Artists in the Schools Program, Chattanooga Area Friends of Folk Music, and various music and folklore festivals.

Several times, prior to leaving Takoma Park for good, Tom and Scott drove to Tennessee to the mountain they both loved. They always returned relaxed, lighthearted and more at peace with themselves. More and more, Scott helped out in the shop, sanding and performing various repair jobs.

“I repaired instruments for quite some time before building, which I feel gave me a broader understanding of the construction of guitars and helped me formulate ideas and opinions about what is important or necessary to the construction of a good instrument,” Scott recalls.

Mary continued to develop her skills on the Autoharp and as a vocalist. She now performs with an ease that displays her talent and her deep love for the heritage she shares with Tom. “I’m very privileged to be able to play music with my family, and it always makes me proud to be on stage with them,” she says.

Mary had mixed emotions about the move to “the mountain,” being at once reluctant to leave behind the friends and activity of the D.C. area, and at the same time eager for the serenity and safety of the home they planned to build on the land that Tom’s family settled on over a hundred years earlier.

Rick began playing bass several years ago, and performs with Tom, Mary, Scott, and other local musicians when his job with the Tennessee Highway Department permits.

Hundreds or thousands of miles away, and years from those early days, Tom’s influence has been and will continue to be felt, even by people who have never met him.

He was never a “famous” performer, doesn’t expect to get rich from what he does. But Tom Morgan is a man who loves the land and heritage that his father, Spurgeon Snow Morgan, left him. He loves the trees that grow on that land, and the instruments that he can create from their wood. He loves his family and the music he creates with them.

Tom’s own words help put this love-affair with bluegrass music in a proper perspective: “It is easy to presume we would be better musicians if we didn’t build instruments, and better builders if we didn’t perform, but this way we can have the best of both worlds.”

Share this article

2 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

I have a banjo thats says monroe on the headstock and thorobred in inlay. I believe it may ne a Tom monroe banjo. Can you help with info?

I also have a 5 string banjo with Morgan in script inlay on the headstock and a MOP insert at the 15th fret with Thorobred imprinted. I also believe this to be a Tom Morgan built banjo. I would appreciate any additional information others may have on this instrument.