Home > Articles > The Archives > Wayne Henderson—Music Making Mountain Man

Wayne Henderson—Music Making Mountain Man

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

February 2007, Volume 41, Number 8

As I pulled off 1-81 at the Marion, Va. exit and headed into the mountains on Rt. 16, I recalled the first time I ever met Wayne Henderson. I had enrolled in a guitar workshop at the Augusta Heritage Center in Elkins, W.Va., and upon arrival at the college discovered that my instructor was Wayne Henderson. It was the first time I ever heard his name. That was in 1992. Now, in 2007, I and just about everyone else in the acoustic guitar family are well aware of Wayne Henderson. He recently sold one of his completely handmade Henderson guitars (an OM-42 model) to Eric Clapton. Just about everyone in the acoustic guitar family knows that name, too!

At an elevation of 3,400 feet, I slipped the transmission into third gear for the long climb up and through the Mt. Rogers National Recreation Area. I passed through Sugar Hill, Troutdale, then into Volney. A right turn onto Rt. 58 (the J.E.B. Stuart Highway), several hairpin turns down the road, and there it was, Rugby Road, “Main Street” of Rugby, Va. population circa 100, give or take a few. A left turn at the First Aid Station, a few more mountain switchbacks, and a right turn onto Tucker Road brought me to the home of the famous handcrafted Henderson Guitars, right in the shadows of White Top Mountain, elevation 5,500 feet, where Wayne selects his indigenous spruce that gives his guitars their unique sound.

I sat in the Jeep for a few moments admiring the sturdy, brick building that houses the tools and talent that craft the Henderson guitars. Wayne has come a long way from that old barn down the road that had been his shop since he started making guitars in earnest around the mid- 1960s. A $10,000 grant from the National Endowment For The Arts provided him with the financial means necessary to make this new workshop a reality. I was fortunate to have been in attendance that special evening on September 29, 1995, in the Lisner Auditorium of George Washington University. I heard, for the first time, Wayne pick the guitar and realized this man was not only a master maker of guitars, but an incredible player as well. Wayne had now become a select member of an elite group of bluegrass music innovators who preceded him into this family of distinguished National Heritage Fellowship members—Bill Monroe, Earl Scruggs, Ralph Stanley, Doc Watson, Ola Belle Reed, and Kenny Baker.

I walked into the shop and Wayne was busy working on a brand new instrument. This prized guitar would be awarded to the first place winner of the guitar competition at his 12th Annual Wayne C. Henderson Music Festival & Guitar Competition “always held the third Saturday in June,” as he likes to say. The proceeds from the festival, held at Grayson Highlands State Park, support the Wayne C. Henderson Scholarship Fund that provides incentive for young people in the mountains who want to pursue the study of bluegrass and old- time music. This man is multifaceted for sure—internationally renowned luthier, picker extraordinaire, and benefactor to the young people of the mountains.

Unless you’ve been to his shop, it’s difficult to describe the bee hive of activity that unfolds before your eyes. No sooner do I get out a “Hi Wayne” greeting, the phone rings. It’s a customer who needs a fret job on his mandolin. “Well, I got a feller here who’s doing a story, but c’mon over, about noon…O.K.” Wayne and I exchange a few more pleasantries and the phone rings again. “Hello…uh huh…I’m planning to be there around five. Yeah. I’ve got a feller here who’s doing a story.” He turns to me, “Do you think we’ll be finished by 3:00?” I nod in the affirmative. Wayne confirms his arrival time for 5 p.m. As he hangs up the phone, he explains that he’s giving a concert that night at the Rex Theatre over in Galax with a few other folks. “It’s going out over the radio!” Mercifully, Wayne turns off the phone.

I start thinking that I’d better get his ear, or I won’t get a story. I ask, “Would you like to go over to the house and do the interview?” Wayne agrees, “Yeah, I think that would be a good place.” As we start to walk out the door of the shop, up pulls a car and out steps a fellow with a discernable foreign accent, carrying what appears to be an old worn down guitar case. “Hello, Wayne,” he says, “I’m Timon van Heerdt. We met last week at MerleFest and you said I could stop by to see the shop!” About face.

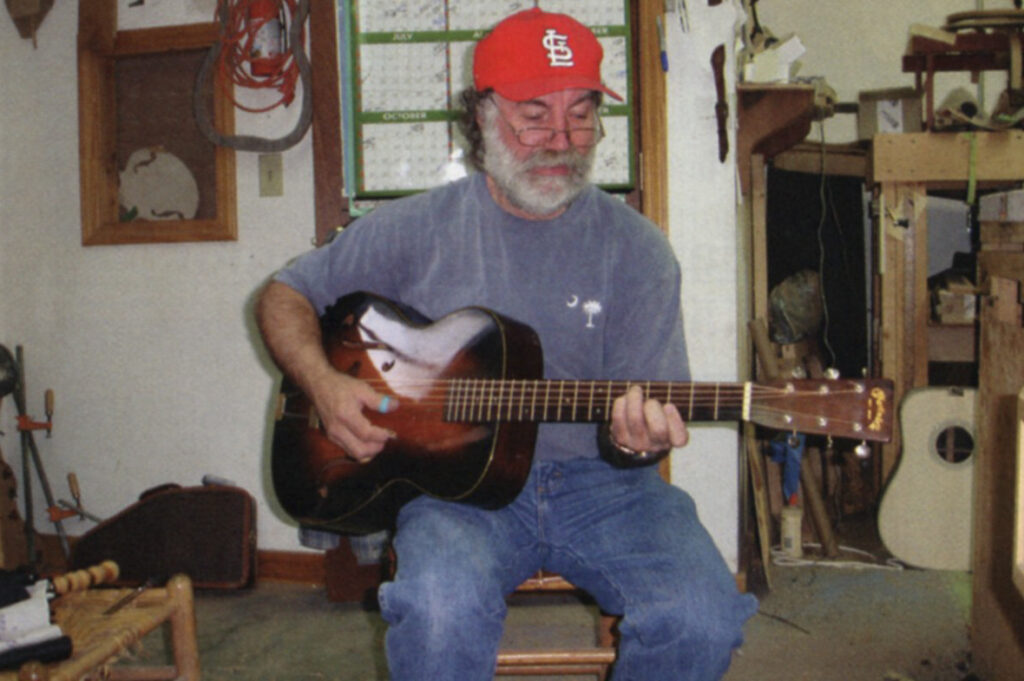

Now, we’re gathered around this intriguing case and I see the wonderment welling up in Wayne’s eyes. Gently, he opens the case and, voila, a moment of ecstasy. He lifts the Martin guitar out of the case, holds it up, and slowly turns it around.

“Where’d you get this? I don’t think I’ve ever seen one. Is it a 1934?”

“No,” the gentleman replies, “1936.” As Wayne absorbs all the unique aspects of the guitar, arch top, F-holes, a larger sound box than the standard, I figure I’d better say something, or he might forget I’m there. “Looks like an early D-18.”

Both men reply, “Not a D, an R-18.” Now I know I’m going to be here for awhile! But to my good fortune, it turns out that Timon (rhymes with Simon) had also brought along his camera from Holland, and he started taking photos. Being without one myself, I quickly seized the opportunity. Timon was more than willing to do the shoot for this story.

We finally escaped from the shop and set up in Wayne’s kitchen. Wayne took a few minutes to explain that the house was built in 1939 by his father and uncles. These men were farmers with a multitude of skills. “When you live in the mountains, you have to be ready to do most things yourself,” Wayne explained. “They were into music, too…would play some shows. They called themselves the Rugby Gully Jumpers. My brother, Max, and I used to play with them on the radio station out of Galax.” We began the interview with the hot topic of the day, Eric Clapton’s guitar.

So, how did a world famous guitar player from over in England ever hear about Wayne Henderson’s guitars in the mountains of Rugby, Va.?

Well, a friend of mine, Tim Duffy, was demonstrating some new recording equipment in New York, and Clapton was going to be there. So I suggested to Tim that he might want to bring along the guitar I’d made for him, not to sell him one, but just to see what he might say about it. So he did. Well, Clapton saw the guitar and played it, and they taped him playing, and he was really bragging on my guitar. So he decided to order one.

Wayne went on to explain that it took all of 12 years from that point to where Clapton actually got the guitar. As Wayne put it, “When I got the order to build him a guitar, I put it aside. I knew they wouldn’t be calling me up all the time or bugging me for it. But he did want one. I might never have made him one, but this friend of mine, Allen St. John, said I ought to make it for him and Allen would write a book about it. So I got real busy on it and made two identical guitars with consecutive numbers. Eric Clapton bought the first of the two guitars and Allen St. John finished the book Clapton’s Guitar, published by Free Press in 2005. The second guitar was sold at auction on May 16, 2006, through Christie’s Auction House, New York City.

At this point in the interview, Wayne remembered that he had that fret job to do. Looking out the window, he saw the customer’s car in the driveway, so over to the shop we went to meet Don. By now, Timon was like an old friend and he kept on shooting pictures as Wayne went to work on the mandolin. It’s fascinating to watch Wayne, the luthier, in action. He seems to leave the scene and go into another zone somewhere, known only to him. With uncanny concentration, he ignores everything around him and “operates” on the instrument. He doesn’t waste a second—down-tunes the strings, pulls them aside and goes to work on the frets. His sense of touch is legendary. His pitch is perfect. As he re-tunes the instrument and proceeds to rattle off several fiddle tunes in his unique style, we all stand there in amazement. Then begins a medley of Carter Family songs. I moved right in with the vocals. I’m ready to climb White Top Mountain with him and pick and sing. We bid Don farewell as he backs out onto Tucker Road, and back to the kitchen we go. Wayne is starting to show signs of, “I’m running short on time,” so we talk for another half hour.

Who are some other artists that have one of your guitars?

Well, there’s Peter Rowan. He’s got one. He about wore it out he played it so much. Norman Blake has one. Gillian Welch. I made her one for appearing at our festival a while back. Tommy Emmanuel from Australia has one. He’s one of the best players I ever heard to play one of my guitars. I’m building one right now for Doc Watson. I made a mandolin for Doc a while back, which he uses. He has an incredible ear for the music. And Clapton has one now.

When did you first become acquainted with Doc?

It was back in the late ‘60s. I was over in a music store in Boone, N.C., and I was pickin’ with a friend of mine. We were pickin’ “Cannonball Blues” and all of a sudden I heard this feller start to sing, and it was Doc Watson. He had been standing right behind us and I didn’t even know he was there. He’s one of my heroes. I’ve worked on his guitar, made a few records with him. We’ve been on a few shows together.

Who were some of your earliest mentors, people who got you pointed in the direction of making guitars?

It’s kinda hard to remember. I’ve been doing this, seems like, all my life. My dad bought me a little plastic guitar—like a ukulele…had a crank on it—when I was about three or four. When I was a little boy going to school, I used to carve toys, people’s initials on their pencils, stuff like that. I just always liked to carve. As I grew a little older. I got to know “E.C.” Estil Ball, a great guitar player and songwriter from around here. He ran a store down the road. He had a real nice guitar, a 1949 D-28 Martin, the only one anywhere around here. It had steel strings on it, looked real nice, and I really liked it. He’d let me play on it once in a while. In those years, it was hard to come by instruments and things here in the mountains. No one had that kind of money to buy one. So I decided that I’d try to make one on my own. I made a pencil copy of E.C.’s guitar and started to build one myself. My mother was a big help. She encouraged me…let me start building it right in her kitchen. But it made such a mess, that she sent me out to the back porch and I worked on a bench out there. I made that first guitar from some wood that was around the farm. I took the veneer from inside my mother’s dresser drawer to make the sides, got some black rubber glue from my dad that he used to keep the weather stripping on his truck. It was all working out fine—this was during the summer when I was off from school—until one hot day in August when the heat went to work on that guitar and it kind of blew up.

Obviously, you weren’t discouraged by that setback.

No. I didn’t say much about it, but my dad knew that something had gone wrong. So he told me that when he had a day off, we’d go over to visit Albert Hash. To meet Albert was a life changing experience for me. He was an expert instrument repair man and made instruments, too. He gave me some tips on what to do, gave me some mahogany wood, and some Weld wood glue, and that’s when I started my next guitar. I used a piece of mahogany and some other stuff Albert gave me. It was hard to come by materials around here. To make the bridge pins, I had to saw a piece of bone off of a dead cow and cut and file the bone down into six pins. It was very labor intensive, hard work…took me almost two years to make that one.

Did you give that guitar the 001 serial number?

No, but the next one I made was #001. I still have that guitar. I was going to sell it, but my mother talked me into keeping it, and I still have it. Each one I’d make, I’d sell for cash or trade for tools. The next one, #002, I sold for S40 and a case. I took that money and went to the saw mill, bought some lumber, and built my first shop. It was about 12×15 feet, right out behind my mother’s house. And that’s where I started making and selling my guitars. It made me realize that I didn’t need to go into farming or take a lot of schooling. I could make a living by doing what I liked to do, making and selling guitars, and I ’ve been doing it ever since. I started getting known around the area, and one day a moonshiner we knew showed up with a man we didn’t know, and we were a little suspicious about him, didn’t know if he was a crook or hiding out. But he wanted to play one of my guitars. He played real good. After a while, he asked me how much I wanted for the guitar. Well, I was a little scared by him and didn’t really want to sell him that guitar. So I thought if I gave him an astronomical price, I could scare him off. I told him I wanted S500. Now that was a lot of money back then. I’d never seen that much. He left and said he’d be back next week. Well, sure enough, he shows up, alone this time, and wants to play that guitar. So he plays it awhile and then takes five $100 bills out of his shirt pocket and gives them to me and took the guitar and left. That one was numbered 007. (Wayne went on to say that he eventually got that guitar back and still has it. It’s got bullet holes in it.)

So how were you able to get your reputation out beyond the mountains?

Well, there was a lady in the area named Etiole Berry who ran a crafts co-op called the Roof Top of Virginia. This crafts coop ran a booth over at the Galax Fiddler’s Convention and they’d sell the crafts of the mountain people. She’d visit with my mother each year, for some of her work. Mother was an expert at craftmaking. On one of Miss Berry’s visits, she saw my guitars. She liked them so much, she said I should put them in the Virginia State Fair, which I did. Well, that led to the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. That’s where I got to meet Norman Blake, John Hartford, and Elizabeth Cotten—she’s another one of my heroes…played the smoothest fingerpicking style left-handed, with the guitar upside down. We all hung out together. Next thing I know. I’m on a tour for the government, playing with them.

By this time. I would think your reputation for picking the guitar was on a par with making guitars.

Well, I started going to guitar contests and worked real hard for my first time at the Galax Convention. I took third prize then. I still go into that competition. Over the years, I’ve won about 14 first-prize ribbons over there. But one ribbon that I still have is the first one I ever won. It was in 1967, the Fourth of July on White Top Mountain. Back in around 1933, Eleanor Roosevelt had come there, and people from all over this area came out to see her. Well, they started up a contest each year which went on until about 1940, when it all fizzled out. I guess the war had something to do with that. But it started up again and that’s when I won my first first-place ribbon. And that’s where I hold my festival each year now, always on the third Saturday in June.

And now you’re making recordings as well as guitars.

I made my first recording with Ray Cline from Statesboro, N.C., on the Heritage Record label. Ray was an outstanding guitar player and it was a great experience to record with him. Flying Fish Records put out an album called “Rugby Guitar.” Hay Holler Records, I did about three with them; one with Steve Kaufman, “Not Much Work For Saturday.” I’ve worked with Butch Robins, Rickie Simpkins. I just finished a new CD on the Kentucky Road label, available with Allen St. John’s new book Clapton’s Guitar.

A quick glance at the clock on the wall told me it was time to wind up the interview. Wayne was mentally tuning up for his Saturday night appearance at the Rex Theatre in Galax. It would be a busy weekend for Wayne. Most of them are now. Sunday was booked with an afternoon concert, followed by a visit with his daughter up in Roanoke. On Monday morning, a TV appearance over in Bristol with H.W. “Bill” Smith, executive director of Virginia’s Heritage Music Trail, The Crooked Road. Monday evening would be equally as busy— Wayne and Friends would be on stage at the world famous Barter Theatre in Abingdon, Va. It’s no wonder the wait time for a Henderson guitar is eight to ten years.

Wayne invited me over to the live radio show at the Rex Theatre that evening. I told him that I wished I could, but had already made plans for the Carter Fold over in the Hiltons on A.P. Carter Highway. “You’ll enjoy seeing that show,” he said and then added, “Look for a feller named Bill Smith. Tell him I asked you to say, ’Hello’.” With that, I headed back out of the mountains.

As the Carter Fold began to fill for the 7:30 p.m. show, I watched the people filing in. It was not difficult to spot H.W. “Bill” Smith. He stands about 6’5”, energetic and outgoing, greets just about everybody who comes in the door. He mingles well with the folks, emitting vibes of welcome as he moves about the dance floor taking photos. At an opportune moment, I approached him, introduced myself, and told him that Wayne Henderson asked me to say, “Hello.” In an instant, I went from perfect stranger to welcomed friend, someone he wanted to spend time with. “C’mon over here where we can talk,” he beckoned.

Bill began to explain to me just what a difference Wayne has made in this region and how highly regarded he is among the folks in Appalachia. “Wayne is one of the nicest people I know. He is not at all taken with himself or his talent—a regular guy who just happens to be a gifted guitarist and builder of instruments. In short, I really like and respect him. Wayne is very well-known throughout the Blue Ridge region and beyond, among people who know good music and good instruments.” Without hesitation, Bill expounded on what Wayne means to this region and to The Crooked Road, that 265 mile stretch of mountain road that runs through Appalachia from Breaks in Dickenson County over to Rocky Mount in Franklin County. “Wayne is one of its featured and most loved performers,” he continued. “His support of the project has been continuous and has always been most welcome. The fact that Wayne has offered his name in support of The Crooked Road is treasured by the board of directors and the staff. Wayne has been willing to help in every way he can to make The Crooked Road a success. He is continually in demand for performances. Whatever Wayne’s future holds, I am sure that he will remain that very nice guy from Rugby who happens to be a world-class musician and instrument maker.”

I couldn’t agree more with Bill. For me, it was a perfect conclusion to a most enjoyable, educational, as well as inspirational weekend with people who are genuinely friendly by nature and inhabit the most beautiful mountains of southwest Virginia.