Home > Articles > The Archives > Get Ready for The Grascals

Get Ready for The Grascals

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

May 2005, Volume 39, Number 11

It was me and John and Paul, the best friends you ever saw. The lyrics from a new Harley Allen composition, released last February on the Grascals’ Rounder Records debut, is the poignant story of three friends who stick together—and stick up for each other—all through school. After one joins the service and dies a hero’s death, the three are reunited…but this time at a gravesite.

The friendship portrayed in the song reflects a similar camaraderie, on both musical and personal levels, found in the Grascals. With bluegrass veteran Terry Eldredge (described by bandmate Danny Roberts as “everybody’s favorite singer who’s never been a frontman of a band”) at the helm providing most of the emcee and lead vocal work, the Grascals are already being called the next new supergroup of bluegrass music, following in the steps of bands like Mountain Heart, Blue Highway, and IIIrd Tyme Out, who started out as new combinations of already well-known artists.

The combined resumes of the Grascals represent decades of experience, including invaluable years learning from bluegrass legends like Bill Monroe, the Osborne Brothers, and Jimmy Martin; as well as stints with Opry stars like Lonzo & Oscar, Wilma Lee Cooper, and Mike Snider; and gigs with country superstars like Garth Brooks and Dolly Parton.

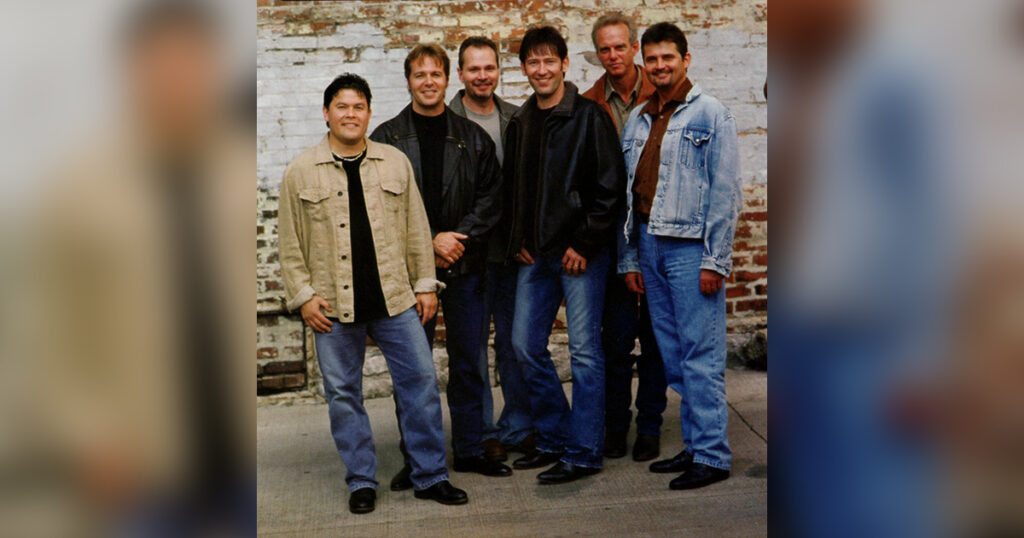

Complex webs of connections bind Terry Eldredge, Jamie Johnson, Jimmy Mattingly, David Talbot, Terry Smith, and Danny Roberts. Guitarist Eldredge and bass player Smith shared the stage with the Osborne Brothers for ten years.

Fiddler Jimmy Mattingly, who joined Spectrum with Bela Fleck, Jimmy Gaudreau, Mark Schatz, and Glenn Lawson straight out of high school the weekend after he won the Grand Masters Fiddling championship, also played a couple of stints with the Osbornes. Mattingly, one of country music’s highest profile fiddlers after years of touring and television appearances with folks like Garth Brooks, Reba McEntire, and Dolly Parton, and mandolinist Danny Roberts (co-founder of the New Tradition and more recently with Ronnie Reno & the Reno Tradition), grew up on adjacent farms in Leitchfield, Ky.

“We’ve known each other since the seventh grade,” Mattingly says, “and pretty much every hour of every day, we were doing something together. It was either playing music or hunting, or doing something crazy.”

Eldredge and guitarist/vocalist Jamie Johnson are both from Indiana, with a common passion for the Osborne Brothers repertoire. In vocal tone and quality, Terry and Jamie sound remarkably like the early Osborne Brothers themselves—or at least cousins.

Canadian banjo master David Talbot and Terry Eldredge worked together with Larry Cordle & Lonesome Standard Time for five years.

Eldredge and Mattingly were both members of Dolly Parton’s Blue-niques band a couple of years ago, touring in support of her bluegrass-flavored recordings on the Sugar Hill label, with Talbot joining in for selected television dates.

Terry Eldredge and Jamie Johnson worked together in the Sidemen, Nashville’s favorite Tuesday-night bluegrass band at the Station Inn, for several years. Terry Smith, an original member of that group, as well as Talbot and Mattingly, all substitute occasionally with the band. It was onstage with the Sidemen where Eldredge, Johnson, and Talbot honed their impressive vocal trio, which is the heart of the Grascals’ sound.

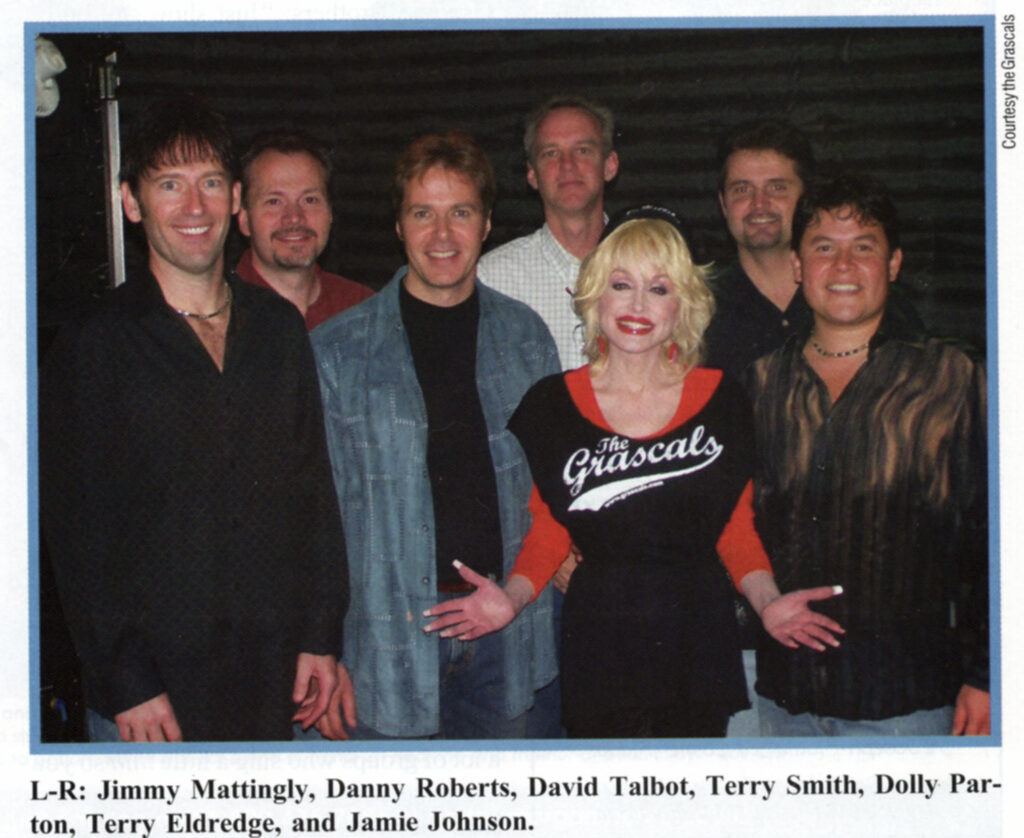

“It feels like fate that this has happened,” Mattingly comments, “because too many things fell into place in a relatively short time.” After being signed to Rounder Records just months after making a demo, the Grascals were tapped to open for Dolly Parton’s Hello, I’m Dolly 2004 fall/winter tour—with a break during rehearsals to showcase at the IBMA convention and perform at Fan Fest in in Louisville, Ky., last October. Their debut on the Grand Ole Opry in February came just days before the national release of their self-titled album. On December 4th, a single from the new recording, a traditional bluegrass version of the Elvis Presley hit, “Viva Las Vegas,” recorded as a duet with Parton, debuted at #3 on Billboard’s Country Singles Sales chart, where it remained in the top ten for five consecutive weeks. The song also entered the all-genre Hot 100 Singles Sales chart at #27.

“I am so proud of the Grascals,” Parton says. “They are one of the best bluegrass bands I’ve ever heard. Their new CD is one of the greatest albums I’ve ever listened to, and the fact it’s their first just tells you how talented they really are. I was very proud to get to sing on ‘Viva Las Vegas’ with them. They have been opening my shows for a while and people just love ’em.”

In addition to originals from Jamie Johnson and David Talbot, the new recording includes standards like “My Saro Jane” and “Sally Goodin” (with all the fiddle parts), and the gospel favorite “Sweet Bye And Bye.” Bobby Osborne, who rarely guests with anyone, makes a point to appear live with the Grascals whenever his Opry and touring schedule permit. In fact, he has become something of an adopted uncle and musical mentor for the new band. On the CD, Bobby joins Eldredge and Johnson in a chill-bump-raising trio for the Osborne Brothers classic “Some Things I Want To Sing About,” and he plays mandolin on “Leavin’s Heavy On My Mind.”

Calling the Grascals “one of the better groups” in bluegrass today, Bobby says, “For the last 12 or so years, Terry Eldredge, Jimmy Mattlingly, and Terry Smith have been a big part of my life as members of the Osborne Brothers band, and so when they asked me to be a part of this CD project, it was certainly a great honor for me.”

Signed with CAA, the Grascals have a long list of appearances slated for 2005, including Wintergrass in Tacoma. Wash.; the Gateway City Bluegrass Festival in St. Louis, Mo.; the Festival in the Pines in Rocky Mount, Va.; the Bill Monroe Bluegrass Festival in Bean Blossom, Ind.; and the California Bluegrass Association Bluegrass Festival in Grass Valley, Calif.

Along with individual name recognition, the members of the Grascals bring a series of lessons learned as journeymen in past bands. From his years as a sideman with Lonzo & Oscar, Terry Eldredge says he learned to “just have a good time and let that show through to the audience.”

From Jimmy Martin, Terry Smith says he learned “to bring something to the show that’s not so generic—something that people want to see, that is unique.”

Smith says Wilma Lee Cooper “always put on a good quality, clean show and was a good lady to work for. From her I learned to be nice to the people; it’s the people who are paying your salary, so to speak.”

Eldredge recalls instructions from Sonny Osborne backstage at the Opry the night he was hired to go full-time with the Osborne Brothers: “Just show up, be on time and be in tune. And know the stuff.”

Terry adds that the Osbornes are his favorite bluegrass band—but he also credits Flatt & Scruggs, Bill Monroe, and Mac Wiseman as huge influences. Fans often point out the similarity between Terry’s and Bobby Osborne’s voices. “I never tried to sing exactly like [Bobby],” Terry says. “It’s a big compliment for people to say that, but I know the difference,” he laughs. “If I could just partially sound like him, it’d be fine with me. I think he’s the best bluegrass singer that ever lived.”

Eldredge says it was easy to fall in on the baritone part with Sonny and Bobby “because they both sing so hard and they know their parts so well.”

Smith, who also sang baritone with the brothers, agrees. “You can’t hold back when you sing with those guys. There are a lot of groups who sing a little thin so you can cut corners and do falsetto things, but with them you’ve got to do the real thing because it just won’t work otherwise.” Smith also says he picked up lessons from the Osbornes on “how to handle yourself onstage—with pride, professionally.”

It’s a tossup whether Terry Smith or Terry Eldredge was the biggest practical joker in the Osborne Brothers band during their tenure. However, upon closer interrogation, it turns out that Smith, a mild-mannered father of three who always carries family photos in his wallet, was usually the mastermind of the pranks while Eldredge carried them out. Most of their legendary exploits cannot be recounted in print, but here are a couple of jewels.

“The Bass Mountain Boys pulled a stunt on us one time, which was a big mistake on their part,” Smith recalls. “We played a show with them at Harry Grant’s festival in Wind Gap, Pennsylvania, and we went out right before they came onstage and dropped about five stink bombs. Then they had to come out and play. One of the guys broke a string on purpose, so he could go backstage [to get a breath of air].”

Then there was the joke played on Polly Lewis of the Lewis Family. “Polly always played the tambourine,” Eldredge explains. “At Jekyll Island. [Ga.], in between shows, we got her tambourine and Scotch taped the [metal discs] that jingle. So when she came out to play it, it went ‘thunk’ and there was no sound at all. From that moment on, I don’t think she ever played tambourine again.” Did she ever figure out who did it? “No, I don’t think so,” Eldredge says. “She’ll know now, if you print this,” Smith says, and then deadpans, “We tried doing the same thing with Roy’s banjo one time.”

Terry Smith grew up in a family band in North Carolina, starting off on mandolin at age five—along with his brother, songwriter Billy Smith on guitar, his father Pat Smith on old-time fiddle, and his mother, renowned country music journalist Hazel Smith, on bass. “I learned the G-run on guitar when I was about six years old, and I thought I’d found gold,” Terry chuckles. He picked up bass at age six, standing on a chair to reach the neck.

Terry and Billy own a publishing company with Osborne Brothers fiddler/ Music Row entertainment business lawyer David Crow called Bats and Crows. The brothers also share the sad honor of performing with the late Bill Monroe on his last studio recording session, three weeks before his stroke in 1996. Bill sang on a couple of songs and played mandolin on a third, on their “A Tribute To Bill Monroe” CD for K-Tel Records.

Hazel Smith was a close friend of Bill Monroe’s, so the brothers spent a lot of time in Monroe’s company—sometimes subbing as Blue Grass Boys, and also working on his farm outside Nashville in the 1970s. “The first time I met Bill was around 1967 or ’68,” Terry recalls. “The band I really remember him with was with Roland White, Vic Jordan, Kenny Baker, and James [Monroe] on bass.”

In 1975 or 1976, when both brothers were working at Monroe’s farm, Terry remembers singing quartets in the car with Monroe when they were out running errands. “We’d ride down the road and [Monroe’s brother] Birch would sing bass, Billy sung baritone. Bill sang lead, and I sang tenor,” Terry says, “and Bill would say, ‘You know, that is powerful, right there.’”

About Monroe and Kenny Baker, Smith says, “People who didn’t see them play back in the ’70s have no idea how well those two men could play together. It didn’t matter who else was in the band. They had this strength, this power…it was really something to see, and they had it for a lot of years. I learned a lot from Bill.”

Growing up in Leitchfield, Ky., Jimmy credits his father, a fiddler who played for local dances, as his first musical influence. Danny and Jimmy’s conversations on the school bus most Monday mornings focused on how Mattingly had done at the fiddle contest he entered over the weekend. “In eighth grade, I broke my hip and I was out of school that year,” Roberts says. “I was at home, and that’s when I started playing guitar. Then Jimmy taught me to play guitar with him on fiddle, and that’s how I got started. A year or so later, I started backing him up at contests and kept doing that until he quit.”

From his years with the New Tradition, Danny brings the experience of “seeing all the ins and outs of how hard it is to try and make it. I’ve done everything from booking and managing, to driving the bus,” he smiles.

Roberts, whose guitar hero was Tony Rice, also credits Sam Bush and David Grisman as influences. “I think as you mature, you tend to try and get back to the basics,” he notes. “I’ve gone back and listened to what Monroe did. One of the things I try to do now is think, ‘What can I do that makes the song better?’ instead of ‘What can I do to make myself sound flashy?’” Danny’s day gig now is working as plant manager at Gibson Instruments in Nashville.

Jimmy Mattingly brings a unique business perspective to the Grascals. “I’ve watched a couple of really huge artists do their thing,” he says. “I went out the first year with Rascal Flatts and watched them come up from the start and do mostly good things. I kind of worked with them, to see how to build a career. Garth was a smart guy, a great guy, and he treated everybody well—just a classy artist. Dolly’s the same way—very smart, really nice.”

Eldredge agrees. “She’s putting us out in front of all these people; she’s totally behind us. What else can you say about that? It’s wonderful. I thank God for Dolly Parton. Man, she is so sweet. She cares. She’s as real as a blue sky or a rainy day.” Terry says Parton is “probably the greatest musician I’ve ever worked with. Most people think of a musician as someone who plays something,” he clarifies, “but a musician is songwriting, singing, playing, and arrangement—there are four or five categories. She hears stuff and she knows exactly what she wants, and it’s right every time.

Mattingly is excited about the opportunities for this band. “I’ve seen some really huge things, and you know what? I want to do it huge, too. I feel like a lot of times that some people within the industry don’t think bluegrass can be as big as [other types of popular music]. It’s embedded in their heads to do everything in a small way because that’s just what it is. You know. Dolly doesn’t agree with that, and I don’t either after what we’ve been seeing out here on the tour. I’ve got to admit I’m a little shocked because I didn’t know what to expect, but the people give us a great response. They love the music, and we’re playing hard-core, straight-up bluegrass.”

Onstage, Mattingly has an intensely focused look on his face when he takes a fiddle break. What’s he thinking? “I’m thinking, ‘What would Benny Martin do here?’ or J.T. Perkins.” Jimmy smiles. “I had a fiddle player tell me one time. ‘Don’t play through a bunch of notes to get to another one. Play every note like it’s important.’ I get engulfed in it,” he admits. “For the most part, around a lot of people, I can’t talk or say anything. But when I’m playing, I just get into my own world and then there can be ten million people and it wouldn’t matter because it’s between me and that fiddle. I always liked what Sam Bush did on fiddle,” Jimmy adds. “He doesn’t get listed as a fiddle influence a lot, but I’d have to say there’s some Sam Bush in my playing. I like the way he always has drive. When I listen to the old guys like Benny Martin, when they played, they played it like they meant it. Terry Smith said the other day, ‘Those guys didn’t know what they were doing back then. They were just playing what they felt.’ They were playing from their souls, their hearts—and that is what people want to see, more than any kind of flash; something that comes from deep down inside you.”

The youngest Grascal, at age 32, Jamie Johnson didn’t get interested in singing bluegrass music until he was in college. Jamie’s older brother Brad started every morning listening to the Osborne Brothers on albums and eight- track tapes at full volume. “From ‘Rocky Top’ to ‘Muddy Bottom,’ he knew every song they did,” Jamie recalls. “I had to ride to school with him every day and it would about drive me nuts.”

In March 1991, Jamie got a call at college from his parents; his twenty-year-old brother had died in an accident. I went home and asked Mom, and Dad if I could take all Brad’s Osborne Brothers records, as something I could stay close to him with. I put them on cassette tapes and I found out I already knew every one of them by heart. It just built from there. I fell in love with the music, the incredible lyrics and vocals.”

After moving back to Indiana with an engineering degree, Jamie met Tony Holt, son of Aubrey Holt with the Boys From Indiana. “Tony basically taught me to sing,” Jamie says. “Tony’s thing was, ‘If it sounds like horns to you, if it’s got a real buzz, then you know you’re right there.’”

Horns? “When the three voices almost sound like one,” he explains, “you feel almost a vibration off of [the singers]. He’s the only guy I’ve heard say it like that.”

Tony and Jamie, along with Harley Gabbard’s son Harlan, formed the Wildwood Valley Boys in 1992. Not long afterwards, Tom Holt and Jerry Holt retired from music, so Tony Holt and Jamie joined the Boys From Indiana, touring for two years.

Johnson didn’t learn how to cook pork rinds like reso-guitar player Harley Gabbard. But what he does bring to the Grascals table is the Boys From Indiana brand of “personality, and being able to deal with the folks and always having a smile on your face,” he says.

Johnson moved to Nashville in 1997, after meeting Terry Eldredge at a festival in Florida. “I told him all about my brother Brad and what a fan he was of Terry’s and the Osborne Brothers,” Jamie says, “and man, that guy took me in as if we’d grown up together.” Jamie picked up a full-time job with a steel company in Music City and started sitting in with the Sidemen, eventually joining the group full-time to cover the late Gene Wooten’s tenor parts when Gene was in failing health and not able to sing.

Johnson learned the importance of singing with confidence and how to focus on lyrics while watching Eldredge onstage. “[Eldredge] lives each song he sings,” Jamie marvels. “That’s what I learned from that guy. If he’s singing a real sad song, he’ll make himself cry before the end of the song.”

The secret, Eldredge says, is to “pay attention to the words. When you talk to somebody, you’re not just rambling through it, are you? You’re saying what you mean and what you feel. Well, do it the same with a song. Pay attention to what you’re saying and the feeling in that. Listen to the words.”

Although most people outside southern Ontario had never heard of him when he arrived in Nashville in 1998, Canadian-born David Talbot had already been playing the banjo and studying bluegrass music seriously for 25 years. “Dad had those old Flatt & Scruggs 78s and records, and when I was ten, a banjo came into our household,” he says. “What happened was, when Dad was at work I’d sneak into the case and I just naturally latched onto it,” David says. “Some kids are attracted to toy cars. For me, it was this shiny, fancy banjo. I just couldn’t get it out of my mind from day one. I remember sitting at school with my hand on my leg, picking, imagining a banjo on my knee.”

David subscribed to bluegrass magazines, discovered County Sales, and his dad started taking the family to festivals in the mid-1970s. “I got to see first-hand some current pros like J.D. Crowe,” Talbot recalls. “Crowe, at the time, was only 37 years old—younger than I am now. It was quite an impact; that timing and that tone really affected me. more so than any banjo player I’d ever heard.”

After high school, David played full time with Canada’s longest-running bluegrass band, the Dixie Flyers, for two or three years, winning a number of banjo competitions up north. Talbot began a career in accounting, but his heart wasn’t in it. He wanted to play the banjo. “I instinctively knew that Nashville was the place to go to, because it seemed to me that there was this hub of music that seemed to center there. I thought. ‘If I don’t do this now. I’ll always wonder…what if?’”

Talbot’s reputation as the banjo player who is “a cross between Earl Scruggs and Larry Perkins,” as Rob McCoury put it, spread quickly. In March 1999, David got a call from Larry Cordle to join his band, and three months later, they were in the studio cutting “Murder On Music Row.” Two new friends in town, Aubrey Haynie and Bryan Sutton, began recommending Talbot for recording sessions and soon he was on the short list of players to call for both country and bluegrass studio gigs. One of the biggest highlights so far was recording on Haynie’s “Bluegrass Fiddle Album” with Tony Rice, Sam Bush, and Barry Bales.

Along with the stellar picking and soaring vocal harmonies, a big part of what gives the Grascals star appeal is the natural charisma of Terry Eldredge and the way he always connects with an audience. His influences come from unlikely sources. “Mom and Dad and I used to watch variety shows on TV like The Dean Martin Hour. I was a huge fan of his—still am,” Terry says. “The Glen Campbell Hour was another one, and The Carol Burnett Show. They had great variety shows on in the 1970s up until the early ’80s. So I guess I learned whatever you think I got from them,” Terry grins. “And of course, Elvis.” Interestingly enough. Eldredge is a huge fan of artists like Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, and Tony Bennett. He says, “If I wasn’t doing what I’m doing now, I’d love to play the upright bass in a big band like that.”

After years of performing in other bands, the Grascals is a second chance for all of the members on several different levels. When musicians hit their forties, many times they have to be enticed by a near-perfect situation to leave family and more convenient jobs closer to home. A band like the Grascals doesn’t come along every day, though, and Eldredge, Smith, Talbot, Roberts, Johnson, and Mattingly realize that.

Terry Eldredge, who was in a serious car accident in 2001 that almost took his life, has a more serious perspective than he has ever had about his music and this band. “I totally believe in God and I just feel like I was left here,” he states. “I’m evidently here for a reason. I hope it’s to play and sing music, because that’s what I want to do. Music touches everybody. Maybe if nothing else, I was left here to touch one person’s heart and help them out.”

To their fans Terry says, “Thanks for the support all these years. And for the new fans, thanks for jumping on the bandwagon. I hope we can do it for at least another forty or fifty years!”

Nancy Cardwell, IBMA’s Special Projects Director, lives in Nashville, Tenn., and has written about bluegrass music for entertainment publications since 1980. She grew’ up in a family band in the Missouri Ozarks and plays acoustic bass with the Persimmon Sisters, based in Owensboro. Ky.