Home > Articles > The Tradition > Notes & Queries – October 2024

Notes & Queries – October 2024

Q – Have you ever heard of “Red White & the Dixie Bluegrass Band”? Do you know anything about them or when they were active? They came up on Facebook through a mixed artists compilation album and sounded really good! – Wayne Hoffman

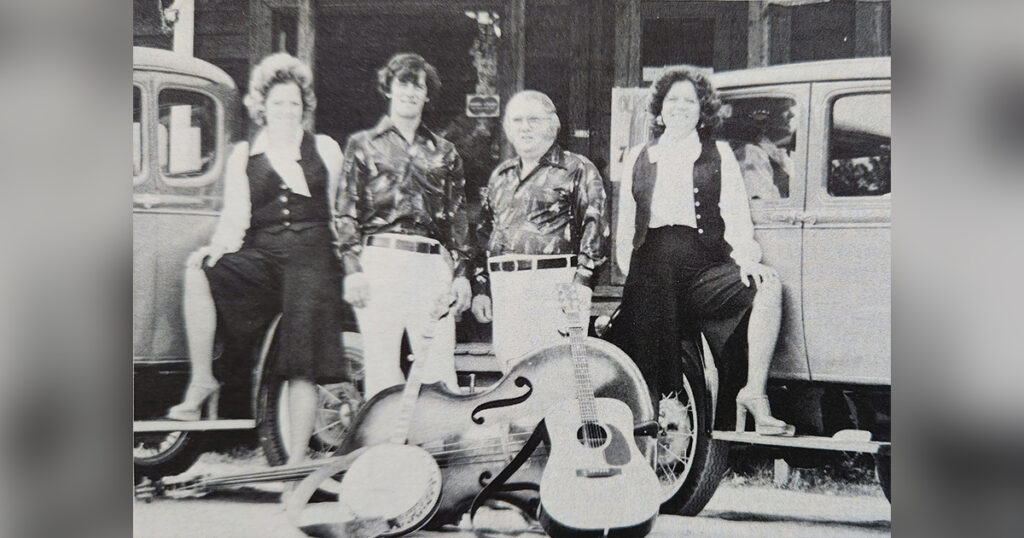

A – Red White and the Dixie Bluegrass Band was a group from Conway, South Carolina, which is located 15 miles inland from Myrtle Beach. As their name implies, the group was headed by William Arthur “Red” White, Sr. (May 11, 1928 – January 22, 2000), a life-long resident of the Conway/Horray County, South Carolina area. White’s World War II draft card listed his hair color as “red,” hence the nickname.

White appears to have gotten his start in the late 1950s or very early 1960s. The first direct evidence of his work was a four-song extended play 45-rpm disc that appeared on the Starday label (SEP 136) around the middle part of 1960. The disc was listed under his own name (no band name was given) and consisted of all gospel material: “Old Daniel Prayed,” “I Will Return,” “Jonah,” and “Which Will it Be?” Two additional EPs soon followed. One was for the Faith label (#1110) and the other was a 1963 release for Starday (SEP 224). The latter disc was listed as being by Red White & the Country Gospel Singers.

Horry County had a long tradition of starting political campaign seasons with events called “stumps.” They were not unlike revivals with music and dinner on the ground; political speeches took the place of preaching. Starting in about 1964, Red White & the Country Gospel Singers performed at both Democratic and Republican stumps.

It was around the same timeframe that White secured a radio program on WLAT-AM in nearby Wilmington, North Carolina. He later hosted a television program over WBTW in Florence. He used his media exposure to bring legendary acts such as Don Reno & Red Smiley, the Stanley Brothers, and Bill Monroe to Conway.

White recorded one of his first long play albums in 1965/’66. It was a collection of hymns that appeared on the Rural Rhythm label (RR 136). While characterizing the album as having been “competently performed,” reviewer Dick Spottswood concluded that the “performances are satisfactory.” An album of secular bluegrass standards (RR 172) appeared the following year. A number of songs from this latter album appeared in a multitude of various artists collections on Rural Rhythm.

White continued performing and recording until the start of the new millennium. By the early 1970s, he had worked several of his daughters into the group. This necessitated a band name change to Red White and the Dixie Bluegrass Boys and Girls.

In the 1990s, White suffered a heart attack and mild stroke, which sidelined his ability to pick. It was then he changed the focus of the band to all-gospel.

In a 2000 article by Steve Wildsmith that appeared in the Sun News (Myrtle Beach), Conway bluegrass entrepreneur Jennings Chestnut observed that “Red White was a pioneer in this county for bluegrass music . . . Every county in the nation has a person who latches on to bluegrass and helps get it started. Red White was that person in Horry County.”

Q – I thoroughly enjoyed the Earl Scruggs stories by Zach Dressel (see June 2024 “Remembering Earl Scruggs at 100”). Do you have any information about when Earl fell off of the stage somewhere in the Carolinas? I spoke to someone who was in attendance who said it was a horrible incident with women crying and rushing him to a hospital. – Walt Crider, Historian, Seven Mountains Bluegrass Association.

A – An Associated Press article that appeared in the Monday, November 28, 2005, edition of the Asheville Citizen Times (North Carolina) reported that Scruggs fell off the stage after completing a Saturday evening performance at the Myrtle Beach Convention Center. Apparently, the glare of the stage lights in the auditorium prevented him from seeing the edge of the stage, and those who tried to warn him. Scruggs struck his head in the fall and suffered a cut above his eye. He was rushed to nearby Grand Strand Regional Medical Center where he received treatment. He was released soon afterwards. A separate Associated Press article, appearing in the December 7, 2005, Salina Journal (Kansas) added that Scruggs received 12 stitches and returned by bus to Nashville shortly afterwards.

Where Is Jim Clark?

Fred Bartenstein emailed recently that he was “sitting with Michael Streissguth at the Columbus Book Festival. The topic of Jim Clark came up and neither of us know what ever happened to him.”

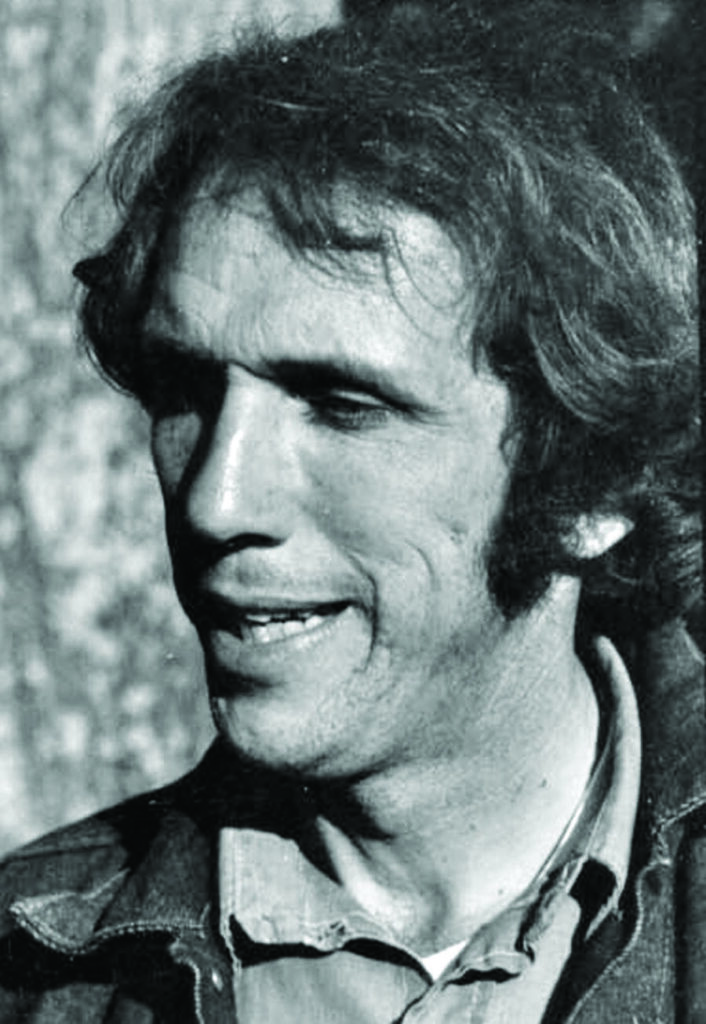

After quite a bit of research, it appears that Jim Clark disappeared from the public radar in the middle 1980s; his activities for the last 40+ years remain a mystery. What many readers might be asking is: Who is Jim Clark?

The short answer is he was a bluegrass festival promoter who was active in the 1960s, ‘70s, and early ‘80s.

Prior to his run as a festival promoter, Clark logged a decade or so as an on-air radio personality. As early as 1956, he had a connection to WARL radio in Arlington, Virginia, and Don Owens, one of the most influential country/bluegrass DJs and promoters in the Washington, DC area. Throughout the late 1950s, Clark’s voice was heard over a number of radio stations in Virginia and Maryland including WPTX in Lexington Park, Maryland; WKTF in Warrenton, Virginia; WSMD in Waldorf, Maryland; and WEEL in Fairfax, Virginia. In fact, it was while at WEEL in 1962 that Clark hosted the first all-night country music program in Washington. That same year, he also became an active member of the nascent Country Music Association.

While Clark most likely featured bluegrass selections as part of his country music programming, the first evidence of his involvement with the genre came on July 1, 1962. That’s when he teamed with Eddie Matherly of WKCW in Warrenton to host a spectacular day of bluegrass at Old Dominion Park in Manassas, Virginia. Talent for the day included Bill Monroe, Mac Wiseman, Jim and Jesse, Bill Harrell, Buck Ryan, Bill and Wayne Yates and the Clinch Mountain Ramblers, and Smiley Hobbs. The crowd was estimated at close to 2,000.

The same duo held forth at the same location for two days (September 1 and 2, 1962) for the First International Country Music Festival. Some of the same bluegrass talent – Bill Harrell, Smiley Hobbs, along with Bill and Wayne Yates and Clinch Mountain Ramblers – was repeated for the event.

By 1965, Cash Box magazine was tagging Clark as a DJ and a promoter. A January 1966 Cash Box reported on a “package [that] was produced by veteran country deejay Jim Clark and was emceed by Clark and Red Wilcox from WKCW-Warrenton, Va.”

Clark’s inspiration for the promotion of bluegrass in a festival setting stemmed from a 1960 one-day event that was staged by John Miller, owner of Watermelon Park in Berryville, Virginia, and Don Owens. The first multi-day bluegrass festival, produced by Carlton Haney, took place on Labor Day Weekend in 1965 in Fincastle, Virginia.

Clark was one of the first to follow Haney’s multi-day festival format. His early festivals, in 1967, took place at Ontelaunne Park in New Tripoli, Pennsylvania, and at American Legion Park in Culpeper, Virginia. The following year, he added a festival at Lake Whippoorwill in Warrenton, Virginia, and later still, a Maryland State Bluegrass Festival at the Take it Easy Ranch in Callaway, Maryland.

At the dawn of the 1970s, the festival movement was gaining momentum. Under the umbrella of the Virginia Folk Arts Society, Clark began producing events that drew on more progressive elements of the music. They were frequently billed as “Peace, Love, Blues and Bluegrass” happenings. His aim was to bring together “the freaks, the long hairs, the Rednecks and conventional folk.” Some people dubbed the events as “bluegrass Woodstocks.” In a few instances, residents located near the festivals, fearing undesirable elements, sought injunctions to keep the festivals from happening.

One of Clark’s champions was Mitch Jayne of the Dillards. In a 1973 edition of Muleskinner News, he noted that “you have to be an opportunist to be a promoter. A gambler with one foot on dry land. I have a great liking for Jim Clark . . . It has to do with a lot of things. His willingness to gamble on such unknowns as the weather, or the nature of the people who would come. I’ve seen the man in his element, without sleep, his engaging stammer stretched out into 14 syllable words meaning ‘maybe’ . . . I love the man, and remember him always, with his face wan and lined like a mummy’s with lack of sleep. Jim doesn’t care how they get to the festival or what kind of refreshments they bring. He just wants them to come and hear what he bought them.”

Throughout the 1970s and into the early 1980s, Clark usually staged five or six festivals each year. He held them in places such as Stumptown, West Virginia; Shade Gap, Pennsylvania; Gettysburg, Pennsylvania; Ripley, West Virginia; and several other locations. To help promote the events, he amassed a mailing list that numbered in the tens of thousands.

By the middle 1980s, Clark’s involvement in festival promotion had run its course, and . . . as mentioned earlier, he vanished from the scene. If any readers have any knowledge of Clark’s post-festival activities, please let us know!

Ronnie Jackson Revisited

The piece on Ronnie Jackson in the August 2024 “Notes & Queries” elicited a comment from eagle-eye reader John Arms in Ohio. He noticed a number of photographs on eBay which dated from the 1970s/1980s, all of which featured banjo player Ronnie Jackson. Of interest to bluegrass fans are images of Ronnie with Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs (together and separately), Jim & Jesse, Stringbean, J. D. Crowe, Gary Scruggs, and even Irene Ryan (a/k/a Granny from The Beverly Hillbillies). Corresponding through eBay, Ronnie reported that he’s still living in Las Vegas, staying busy “promoting my new book” (50 Years of the Television Western), and “selling a few photos.”

Over Jordan

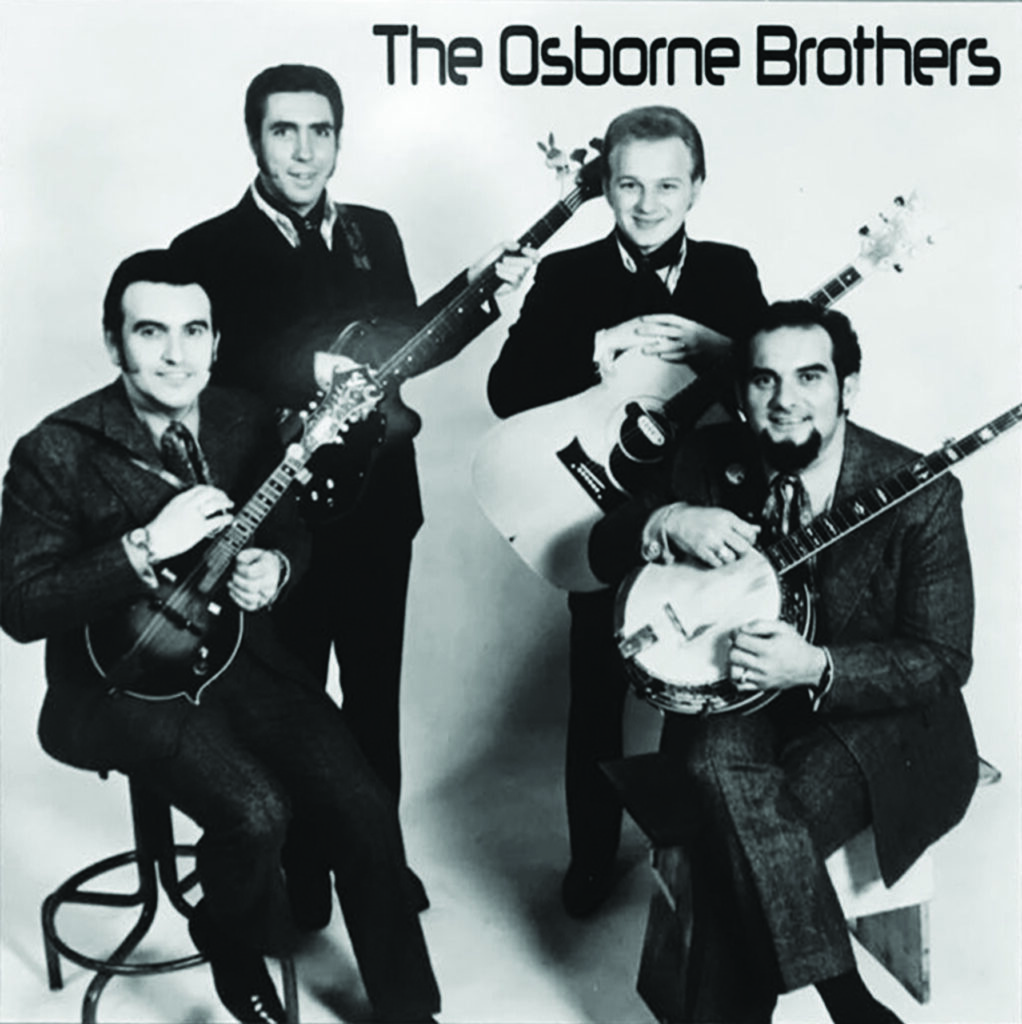

Lurie Ray Kirkland (May 13, 1941 – August 5, 2024) was a multi-instrumentalist and singer from Dothan, Alabama, who is best-known for his work in the 1960s and ‘70s with Opry stars Jim & Jesse and the Osborne Brothers. He also enjoyed stints with country entertainers including Jimmy C. Newman, Grandpa Jones, and Kitty Wells.

Kirkland reportedly pursued a career in country music to escape a life of picking cotton in his native Houston County, Alabama. Like many of his era, he became acquainted with country music through Saturday night broadcasts of the Grand Ole Opry. He learned to play on a guitar that belonged to his mother and by age twelve was making appearances on a local television station.

Kirkland’s first break came in 1961 when, with the help of Hank Locklin, he appeared on the Grand Ole Opry for the first time. Back home in Alabama, he played locally with the Webster Brothers (Earl and Audie) and also with Rebe Gosdin. He continued to make occasional guest appearances on the Opry and in the mid-1960s became a member of Jim & Jesse’s Virginia Boys.

An invitation to join the Army came in 1965 but by mid-1967, Kirkland was back making shows with Jim & Jesse. Band members at the time included Bobby Thompson on banjo and Jim Buchanan on fiddle.

Despite logging over five years with Jim & Jesse, Kirkland did not appear on any of their Epic recordings. He was, however, a regular part of the duo’s syndicated television program.

As the early 1970s rolled around, Kirkland bounded from Jim & Jesse to the Osborne Brothers. He joined Ronnie Reno as a new recruit to the group. He signed on in time to help with the making of the group’s 1971 Decca album Country Roads.

Kirkland’s tenure with the Osborne Brothers lasted slightly less than a year and in the early part of 1972 he made his way to Wheeling, West Virginia, where he joined the cast of Jamboree USA. While there, he assembled the Ray Kirkland Show. He also worked as a folk/country duo with Dave Smith and in 1974 participated in a cross-country tour that was headlined by country singer Dave Dudley.

From 1978 to 1985, Kirkland was an integral part of Opry star Jimmy C. Newman’s show. He served as the group’s bandleader, played banjo and guitar, performed as an opening act before Newman’s appearance on stage, and drove the band’s bus!

Following the stint with Newman, Kirkland worked for yet another Opry act, Grandpa Jones. It was while working for Jones that Kirkland recorded a two-album set called Dixie’s in Alabama. The collection was produced by longtime friend Carl Jackson and featured an A-list of performers including Jackson, Bobby Thompson, Jerry Douglas, Glen Duncan, Mark O’Connor, and Larry McNeely.

Kirkland’s last work with a name entertainer came in the late 1990s when he worked for the Queen of Country Music, Kitty Wells. He considered the opportunity to be a highlight of his career.

Throughout his career, Kirkland wrote and published nearly two-dozen songs, several of which were written in collaboration with Carl Jackson. In the early 2000s, Jackson produced several CDs for up-and-coming singer Alecia Nugent and pitched several of the duo’s songs to her. Nugent’s self-titled 2004 Rounder debut contained the song “Red, White and Blue” while the 2006 disc A Little Girl, A Big Four Lane featured “When it Comes Down to Us (It’s All Up to You).”

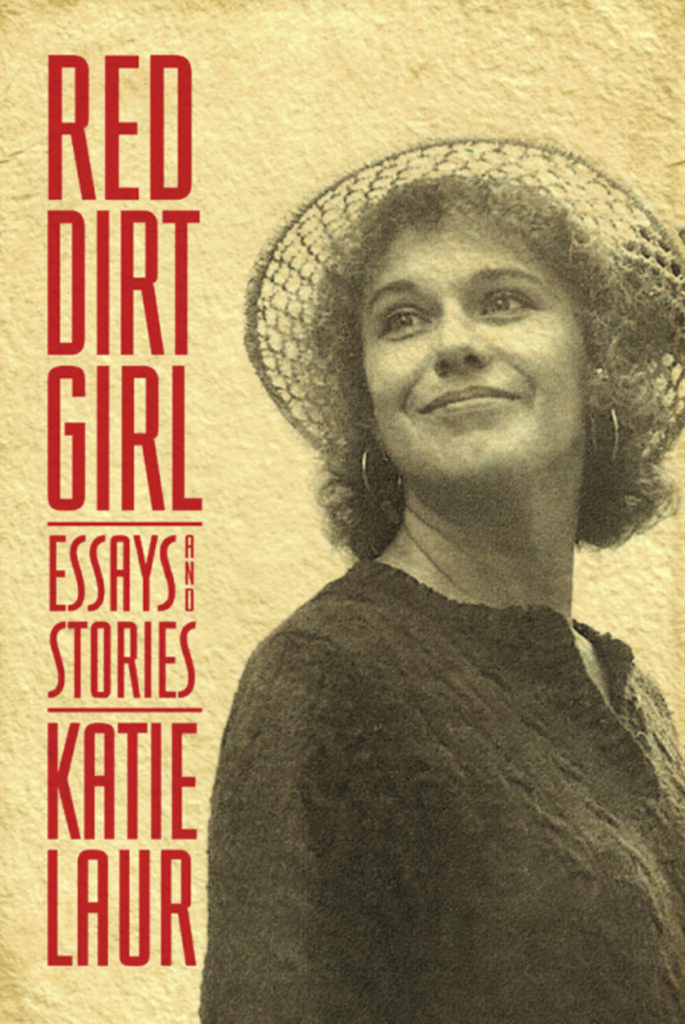

Nancy Katherine Haley “Katie” Laur (January 18, 1944 – August 3, 2024) was an enduring force in the Cincinnati bluegrass music scene for half a century. During the 1970s, she was among the first women to front an otherwise all-male group, the Katie Laur Band, and, starting in 1989, she logged two+ decades behind a microphone as the co-host/voice of WNKU’s Music From the Hills of Home radio broadcast. Laur was also an astute journalist with a keen appreciation of all-things-Appalachian; her written works were collected and published in a 2022 book called Red Dirt Girl: Essays and Stories.

Laur began life in Paris, Tennessee, a small community located approximately 100 miles due west of Nashville. She enjoyed an extended family in the area but later faced moves with immediate family, starting at age five to Detroit and again at age 12 to Alabama. Along the way, she took piano and violin lessons for years and enjoyed making music with her sister and cousins as the Haley Sisters. Later, she attended the University of Missouri where she worked towards a degree in journalism.

The early 1970s found Laur in Cincinnati and in the midst of a divorce. In need of a diversion, friends suggested that she accompany them to see a bluegrass band in town. The group was Jim McCall, Vernon McIntyre and the Appalachian Grass. It was there she found “her people.” Soon, Laur was taking guitar lessons and sitting with the group. She eventually became a full-time member and appeared on the group’s self-titled 1973 album for the Vetco label. Reviewer Frank Godbey noted that “the addition of vocalist Katie Laur is what seems to really tie the group together. Her singing . . . provides a warmth and sensuousness that an all-male group doing the same arrangements wouldn’t be able to manage.”

The Appalachian Grass went through some changes in the middle 1970s and Laur exited from the group. A short time later, she organized her own Katie Laur Band. Initially, the group played locally in Cincinnati. The release of three band projects – Good Time Girl, MsBehavin’, and Cookin’ with Katie – led to increased awareness of the group and touring nationally.

Columnist Marty Godbey cited Laur for “her sweet vocals, with which she can coyly wrap listeners around her little finger.” Plaudits notwithstanding, her path was not easy. Coming of age as a female bandleader in the 1970s, she told Pickin’ magazine in 1977 that she found the task “Hard. Very hard.” She continued, “It wasn’t that people weren’t nice to me, they were. I just didn’t get a lot of respect professionally.” In the end, though, it was the grind of the road that brought an end to the group in the early 1980s.

Although Laur retired from the road, she did not retire from performing. There was, however, a marked shift in performance style. Her singing with the Katie Laur Band was sometimes compared to that of jazz singer Billie Holiday, and it probably came as no surprise to some that she tapped into Cincinnati’s burgeoning jazz scene. Laur was able to work two, three, or four nights a week in town, without having to go on the road. This, coupled with regular contributions to Cincinnati Magazine kept her busy throughout the 1980s.

In 1989, a radio station manager from WNKU heard Katie performing at a Cincinnati venue called Arnold’s. Taken with her performance style and ability to hold an audience, he approached her about hosting a radio program. The show was christened Music From the Hills of Home and ran for three hours on Sundays for twenty-seven and a half years. The program featured an eclectic mix of bluegrass (and all things related to it) and light-hearted interplay between Laur and co-host/engineer Wayne Clyburn. The program was cancelled when WNKU deleted local programming in favor of network news/talk shows. After an 18-month hiatus, the program was picked up by Urban Artifact radio/WVXU-FM.

Laur was the recipient of a 2008 Ohio Heritage Fellowship.

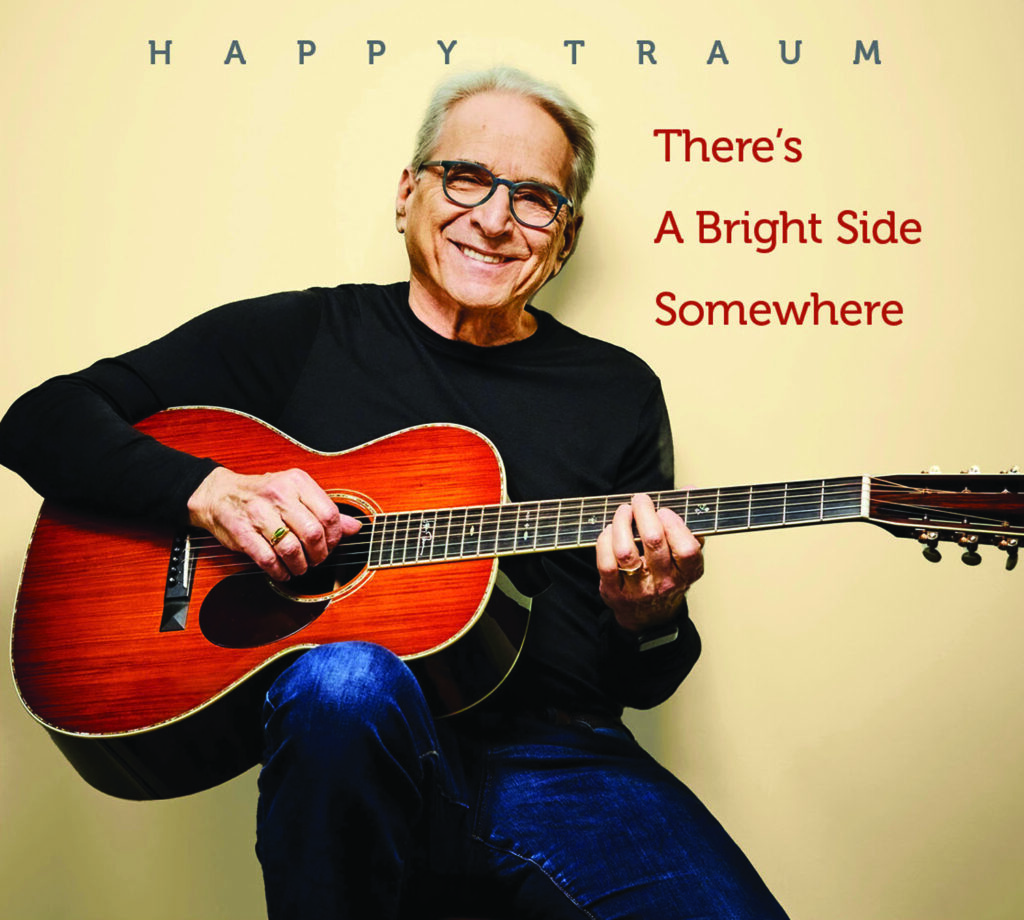

Harry Peter “Happy” Traum (May 9, 1938 – July 17, 2024) was a native of Bronx, New York, who, with his wife Jane, pioneered the use of recorded media for teaching aspiring pickers how to play bluegrass, folk, and old-time music. This was done under the umbrella of Homespun Tapes, a concern that the duo launched in 1967.

Traum’s story began several years prior when Happy was a budding folk musician who specialized in finger-style guitar. In 1960, in the midst of a rising solo career, Happy and Jane married and started a family. To help make ends meet, Happy balanced performing with teaching guitar, a duality that lasted for nearly a decade. In 1967, when the demands of performing made in-person teaching difficult, the idea was conceived of recording lessons on reel-to-reel tapes that could then be shared with his students.

Traum and his growing family had recently relocated to the arts-friendly community of Woodstock, New York. There, working out of the couple’s home – hence the name Homespun, Jane used a makeshift set-up to duplicate copies of the audio lessons. The early lessons were built around an instruction book that Happy published in 1966, Finger Picking Styles for Guitar. Eventually, lessons on other instruments by acclaimed performers such as banjoist Bill Keith and mandolin prodigy Sam Bush entered the Homespun catalog.

The Traums kept pace with changing technologies and transitioned away from reel-to-reel tapes to cassette tapes; they even purchased a high-speed duplicating machine. In the 1980s when home video cassette recorders (VCRs) became readily available, the Traums began producing video lessons. Later, the video lessons were released on DVDs and, later still, as digital downloads. Eventually, the Homespun catalog boasted an impressive array of some five hundred lessons, with teach-ins by now-deceased legends such as Bill Monroe, Ralph Stanley, and Tony Rice.

While the Traums created a very successful business – they reported sales of 180,000 DVDs and CDs in 2006, Homespun was about more than just dollars and cents. Happy related that “I’ve come to realize that we’re filling a need, a service.” Coupled with that was “the number of people that we’ve met and have become close friends with because of it. It’s one of the things that I value most about doing Homespun . . . Everybody that’s on Homespun Tapes I feel are good friends.” Happy and Jane received an IBMA Distinguished Achievement award in 2007.