The Tim Laughlin Band—Heading In The Right Direction

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimted Magazine

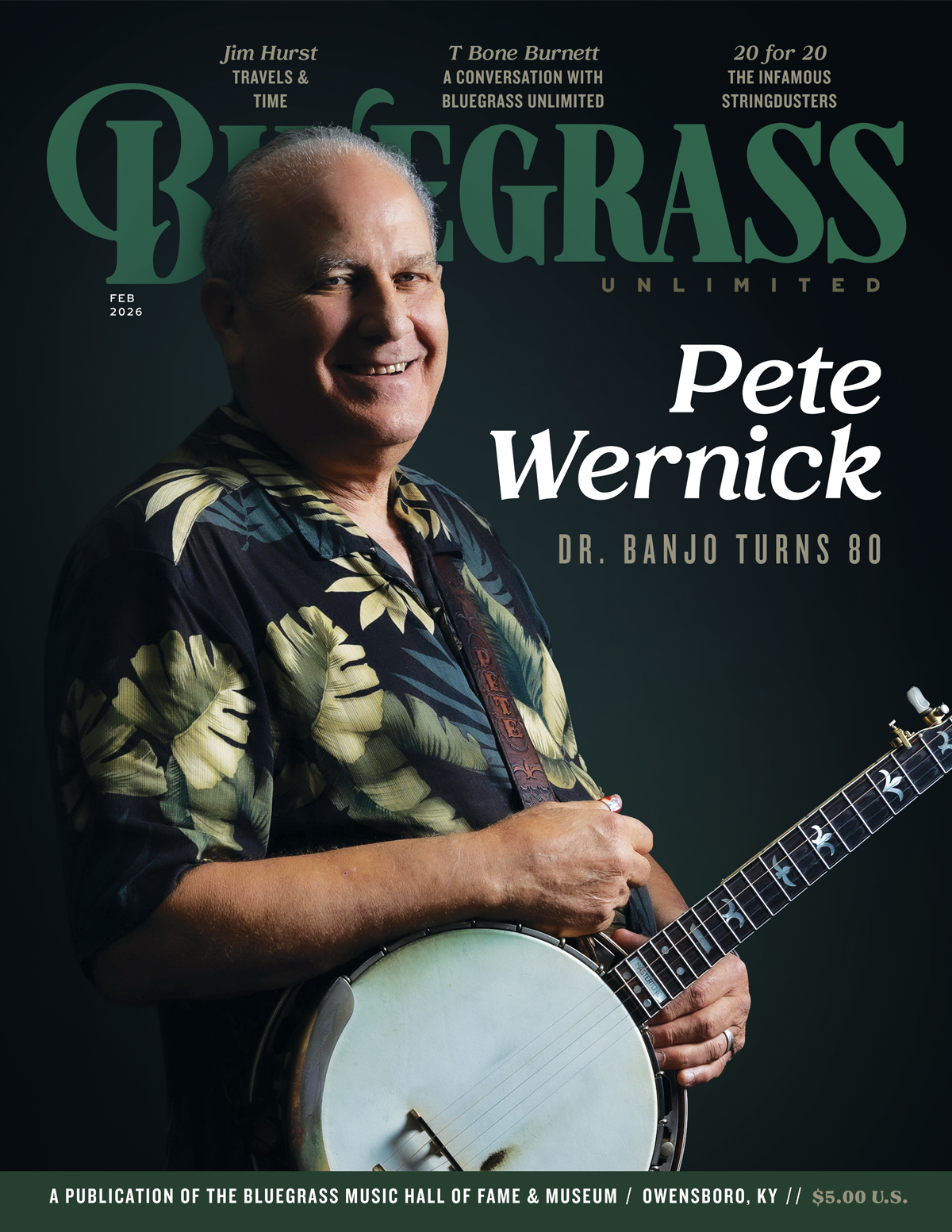

August 1994, Volume 29, Number 2

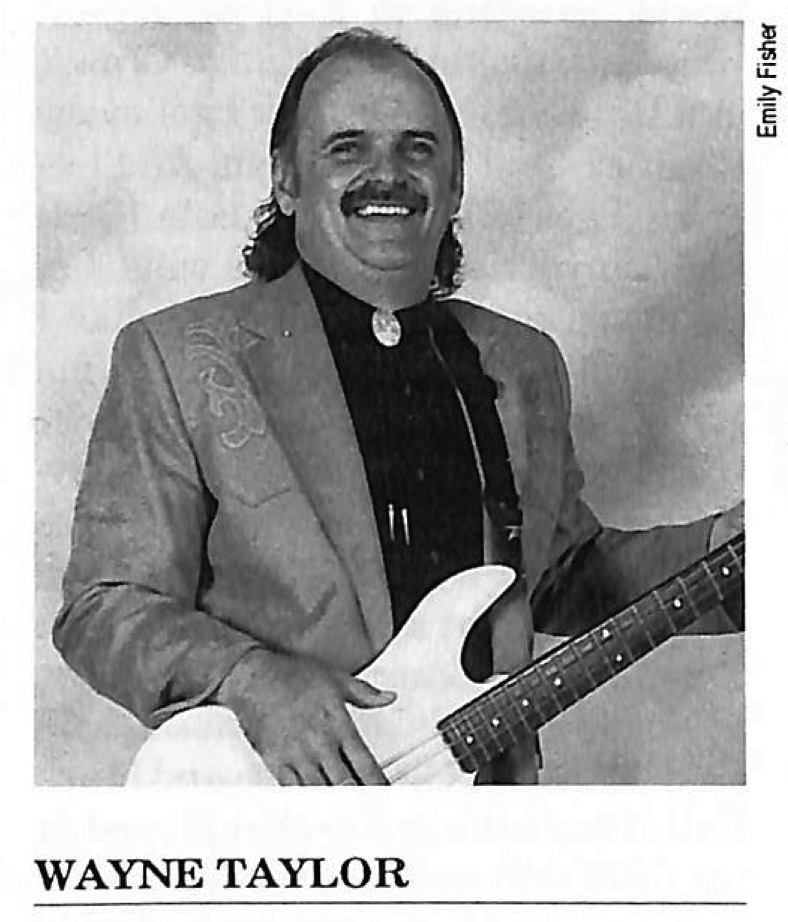

Perhaps it was just ordinary human courtesy, but then again…My wife had accidentally locked our keys in our car while we were at the Jim and Jesse Bluegrass Festival near Elizabethton, Tenn., in June 1993. Our 16-month-old son, Daniel, had a slight fever and was getting a bit cranky after being out in the hot sun for several hours. As I tried to get the door open with a coat hanger that Marshall Wilborn was nice enough to loan me, Wayne Taylor and his wife invited Trish and Daniel up to their trailer for cookies, shade, and cool drinks. It was just what we needed. I thought about the legendary hospitality of bluegrass people, and how it was manifesting itself right in front of me. I looked over at Wayne and said, “You know, you can’t beat bluegrass people.” He grinned and said, “They’re the best in the world.” I don’t think it even occurred to him that I was talking about the Taylors.

Wayne Taylor has been a truckdriver for 17 years, and he has a burning desire to play music for a living at least once in his life. Sounds like a hundred other people you know, right? Well, one difference may be that Wayne has the talent. A gifted singer with a high, powerful voice, a good songwriter, and a bass player with impeccable timing, Wayne has all the tools to carve a living out of this lean beef called bluegrass. And he’s convinced he’s found the right band leader to make his dream come true, mandolinist Tim Laughlin of Bristol, Va.

When he talks about Tim, with the whole band gathered around Teddy Francisco’s living room, he shows an easy grin. “…We’re tickled to death with Tim as the leader of the band. I’ve said several times in the past, I feel like Tim’s the most professional musician that I know. I think he knows how to run a band, and I’m real pleased to be working with him myself. And I’m not saying that just because he’s sitting here!”

But what about the uncertainty of this proposed new life? How to pay the bills? How will his family adjust? “That’s a decision I had to make. Of course, my wife’s behind me a hundred percent. She has a real good job, and that makes my decision a whole lot easier. We talked two or three years ago about putting something together, and at that time, I just didn’t feel like I could quit my job. Now if things are working out to where if we can start working pretty regular, I think I can give up the old truck driving job without any problem at all.”

Now here’s something you don’t see everyday. A local bluegrass band wants to become full-time, and they’re willing to put everything they’ve got into it, including leaving jobs and security behind. They have only a few shows booked, but their bandleader is willing to take all the risks to make this band work. The thing is, there’s certainly no lack of talent in the band. All are accomplished musicians.

Attendees at the 1993 IBMA Bluegrass Homecoming in Owensboro, Ky., got a taste of this talent. The Tim Laughlin Band was the second band to showcase, early on a Tuesday evening—right after, ironically, another group based in the Tri-Cities, the Brother Boys. As a result of the Artists’ constituency meeting earlier in the day, evaluation leaflets filled the tables at the Showcase Lounge for the first time in IBMA’s short history. These evaluations would not only let the artists know what the audience liked and disliked about their show, but also identified the membership category of the respondent (promoter, artist, DJ, etc.).

Afterwards, here were some of the comments about the Tim Laughlin Band: “Very good band I would hire for a festival (from a promoter)…;” “Hard-driving instrumentally, powerful lead vocals (music retailer)…“Instrumentally great…Great original material (broadcast media);” “Good original material, Great banjo player, Great dynamics, Great appearance! (artist).” When asked the things they liked about the show, one respondent—a promoter—said simply “Everything.” Another, a fellow artist, when asked about things that could be changed or improved, replied just as tersely: “Nothing.” Wow. Maybe these guys do have what it takes.

Is there a musician in your neck of the woods who’s played with just about every band within a hundred-mile radius at one time or another? Someone who’s so supremely talented on his instrument that he’s the fellow every band calls when somebody can’t make it? In the Tri-Cities area of east Tennessee and southwest Virginia, that man is definitely Tim Laughlin. It’s no mean feat to be so in-demand in this area. The place where Tennessee, Virginia, Kentucky and North Carolina almost come together has been very important in the history of bluegrass music. It’s also produced more than a few good mandolin players. Think of it: Jesse McReynolds, Pee Wee Lambert, Bobby Osborne, Red Rector, Doyle Lawson, Ricky Skaggs, Adam Steffey…and Tim Laughlin. Tim has nurtured the dream of playing bluegrass for a living now for over 15 years, laboring to prove that he belongs in that elite list, serving time with Larry Sparks, the Lynn Morris Band, the McPeak Brothers and all those local bands. Now this quiet young man believes he’s ready to grab the ring and take the step up to band leader.

Born in Bristol, Va., on July 1, 1964, Tim has been playing since he was eight, but he was originally a guitar player. It came naturally, since there was music in his family. As he recalls, “I had a couple of uncles that played and Mom and Dad played a little bit. My two cousins, Eric and Marty, we’re the same age. We grew up together. But they (his uncles) played a whole lot, you know, back…I can remember when I was six or seven years old, just being around and they would practice all the time.”

Tim switched over to mandolin around the age of 11 when his cousin Eric McMurray got a banjo for Christmas, and Laughlin decided, like Bill Monroe some 50 years earlier, that it would be nice to be different. He didn’t have to look far in the mid-1970s to find a role model for his mandolin playing. Doyle Lawson, from nearby Kingsport, was the top gun mandolinist with the Country Gentlemen at the time, and Tim was immediately drawn to his style. Tim says, “The reason I liked his playing is because he just played clean. You could understand what he was playing. I like other people too, but as far as a good, clean mandolin player, Doyle Lawson is hard to beat.”

Laughlin found himself playing more and more during his teenage years, often at fiddle contests or other instrument competitions. Among the hundred or so crowns he has won are the Virginia State championship on mandolin and fiddle at a contest held at Chase City, and he also claimed the Tennessee State mandolin championship. It would surprise most folks how many such competitions there are scattered within a 150-mile radius of Bristol. “There were some weekends we went to two or three of them at a time. We’d drive and play at one and then drive…it would be 30 or 40 miles apart.”

Often, he would compete with a band and then individually as well. His instrumental wins and his association with top contest bands like Appalachian Trail helped make Tim the ultimate fill-in mandolin player for a plethora of bands from the region. Over the years, Tim has played stints with Plexigrass, Appalachian Trail, Sage Grass, the Boys In The Band, Dusty Miller, Citico Creek, the McPeak Brothers, the Bluegrass Kinsmen, Troublesome Hollow, the Lynn Morris Band, Larry Sparks, and Hazel Dickens, just to name the few he remembers off the top of his head.

Perhaps Tim’s highest profile exposure came during his year-long stint with the Lynn Morris Band, as well as his on going job with Wytheville, Va.’s, McPeak Brothers. The latter connection began when Tim played with the McPeaks at Doyle Lawson’s Festival in Denton, N.C., in 1987, and continues today. The McPeaks—with Tim—also showcased at IBMA’s ‘93 World Of Bluegrass.

During this time Tim has played a variety of different mandolins. “I started out on an Aria Pro II, and I had that thing for about two or three years, and then Thurman Millard, a guy that lives in Bristol, made me one, and I played it for four or five years. Then I traded that mandolin to Alan Bibey’s daddy, and got one of Wayne Henderson’s mandolins and played it for about four years, and then sold that to a guy in Florida. Now I’m playing a mandolin that a guy who lives down in Dungannon, Va., John Fraley, made. I’ve had that one for about three years.”

The decision to form his own band had been brewing in the back of Laughlin’s mind for some time. At first, he and his cousin Eric McMurray, a banjo player, teamed with guitarist Kenny White, now with New Tradition, but this combination didn’t last. Tim had first played with Teddy Francisco in a band from the Tri-Cities called Plexigrass, which competed at the 1985 Kentucky Fried Chicken Bluegrass Championships in Louisville, Ky. And, through filling in with virtually every band in southwest Virginia at some point or other, he met Wayne Taylor—who was playing with Richlands, Va.’s Bluegrass Kinsmen—and another southwest Virginia picker, Joe Clark.

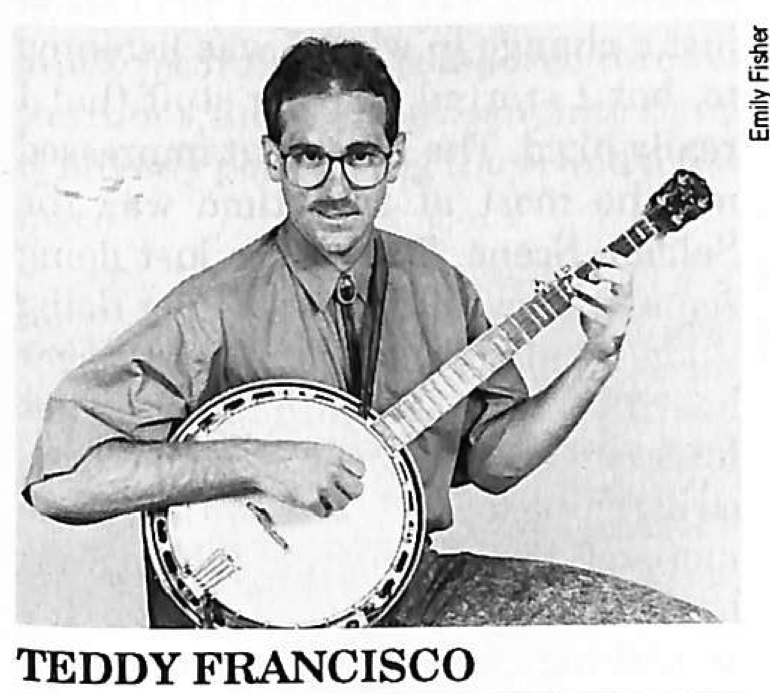

Teddy Francisco won his first clawhammer banjo contest at the age of six. It was only natural that Teddy would play, since nearly everyone in his family did, going back to his great grandfather. His uncles had a band around the Cleveland area of Russell County, in southwest Virginia, where Teddy was born in 1965. The Buffalo Mountain Boys, later named the Rabbit Ridge Pea Pickers, once played at Carnegie Hall. Young Teddy was content to play in the background with his uncles.

But in high school, all the normal testosterone-influenced expectations for American male teenagers prevailed. The way Teddy remembers, “I got into the rock and roll thing, bought me an electric guitar. And then I learned to play saxophone, played in the band.” But eventually, Teddy got back to his roots, with a small but vital difference: “I started playing banjo again when I was about 16, I guess, and…started picking bluegrass, three-finger style.”

When Teddy was 16, it was 1981. Terry Baucom with Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver was creating a new interest in driving traditional banjo, but a new sound was emerging from a banjo player from New York City named Béla Fleck, who had just joined New Grass Revival. The gamut of banjo sounds was available to any young picker, and it all influences Teddy’s playing today: “Well, I started out, I guess like every banjo player in the world, listening to Earl Scruggs. I liked his picking, and J.D. Crowe, and Bill Emerson. I think I got every Country Gentlemen album. And later on, I got to listening to Béla Fleck and Tony Trischka. That’s what I’m into now, really…But now, it’s like I appreciate the Scruggs stuff more… It’s sort of a mixture I try to play.”

Teddy’s first real experience playing in a bluegrass band was Plexigrass, which was also the first time he played in a band with Tim Laughlin. As Laughlin recalls, “The first edition of Plexigrass was myself, Carl Caldwell, Glenn Rose and Mark Ball. That’s the group that played at the SPBGMA contest when they were still having it at Opryland. Teddy joined a little later, and he played with us at the Louisville contest.” This was the prestigious Kentucky Fried Chicken National Bluegrass Band Contestheld annually in downtown Louisville’s famous Belvedere plaza. During the mid-1980s, this contest brought together a handful of the nation’s best amateur bands. Among those competing against Plexigrass in 1985 were eventual winner Radio Flyer of Springfield, Mo., and the Classified Grass from Illinois, which featured a 14-year-old fiddler named Alison Krauss.

After Plexigrass broke up, Teddy freelanced around the southwest Virginia area much like Tim. Not surprisingly, when he self-produced a solo banjo project during this time called “Pick And Roll,” Tim Laughlin was called to play mandolin. The Laughlin Band still does some of Teddy’s original numbers from this album, which caught the ear of fiddler Deanie Richardson in 1991. This led to Teddy’s short stint with Richardson’s band, Second Fiddle. As Teddy remembers, “I got a job with her and played from August or September till the first of the year, and then she went to play with Holly Dunn.”

Later that year, Tim returned from a five-week tour of Europe, and he approached Teddy about forming a new band. These two had picking covered in spades, but they needed a powerful lead and tenor voice. It was a big stroke of luck to find Wayne Taylor.

Wayne was born in Richmond, Va., on January 2, 1955. When he was about two years old, his family moved to the central part of Ohio and spent nearly eleven years there. Then they moved back to the Richlands, Va., area and Wayne has been there ever since.

Unlike the other members of the band, Wayne wasn’t a child prodigy. And he came to bluegrass even later. “I started playing when I was about thirteen, but I didn’t actually get interested in mainstream bluegrass until probably about eight years ago, or something like that,” he says.

The thing that got him interested in bluegrass was that it started to sound different to his ears. “I don’t know if it was actually a change in bluegrass or just a change in what I was listening to, but I started hearing stuff that I really liked. The band that impressed me the most at that time was the Seldom Scene. They were just doing some stuff with John Starling doing their vocals, stuff that I had never heard a bluegrass band do before. That interested me in bluegrass, and I started listening to Doyle Lawson and some more of the mainstream bluegrass bands. I was hooked, I guess. It’s something…well, I don’t want to get away from it, really, it’s something I couldn’t get away from.”

But even earlier, Wayne had been around bluegrass. As he explains, ‘Well, my dad was a truckdriver. And it kind of passed down to me. I would go with him a lot of times on his runs, and of course, he would listen to every country music station in the world. He was a big Jimmy Martin, Bill Monroe, and Ralph Stanley fan, so I cut my teeth on that kind of stuff.”

And unconsciously, Wayne was absorbing what he was hearing. “There are some people that I can recall hearing that really influenced me and I didn’t realize it till later on. One was Paul Williams, who used to be with Jimmy Martin. I think the guy had the most powerful high lead and tenor voice that’s ever been in bluegrass music. I was really impressed with him.”

But Wayne was always singing. In fact, he can’t remember a time when he wasn’t singing. As he explains it, “It was something that came naturally to me. I guess I’m naturally lazy. I don’t really like to practice a lot. I mean, when the band’s together working up material, I love doing that, but just to sit down at home and practice, it’s really hard. And the singing seems to come real easy, so that was something..,! drive a truck for a living, and when I’m driving down the road, boy I can just sing and it doesn’t offend anybody!”

Wayne has played with a number of different bands around the Richlands area, including the Richlands Bluegrass Boys and the Bluegrass Kinsmen. He played with mandolinist Dwayne Compton, now a member of 1992’s Pizza Hut International Bluegrass Showdown winner, Special Delivery. On the Bluegrass Kinsmen’s latest recording, he composed three of the tunes, and the Tim Laughlin Band is already performing these and a few more.

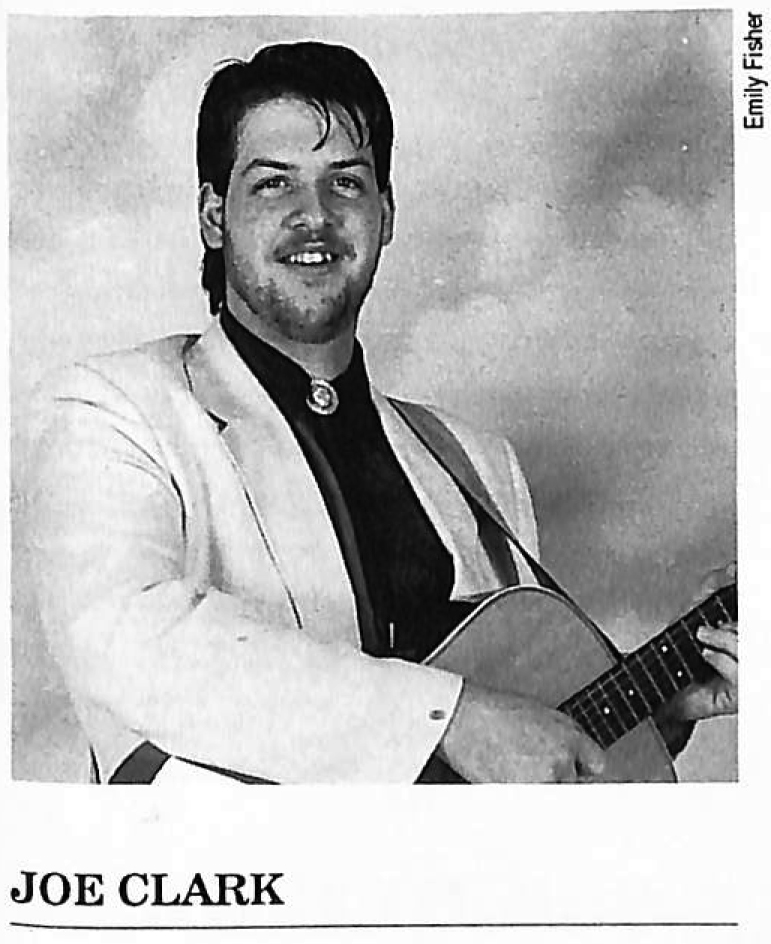

Joe Clark may be familiar to festival-goers from the Midwest. He played two festival seasons with Michigan favorites Wendy Smith and Blue Velvet, whose alumni includes Pam Perry (formerly of Wild Rose and now back with the New Coon Creek Girls), Dana Cupp (of Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys), Brad Campbell of Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver), Jimmy Campbell (of Jim & Jesse’s Virginia Boys), and Richard Bennett (of J.D. Crowe and the New South). But Joe is originally from’ southwest Virginia, and now he’s having a ball being back home and playing with home-grown musicians.

Like Tim and Teddy, Joe comes from a musical family. His grandfather, Don Barrett, was a guitar player with the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers in the early 1950s. Joe’s mother carried on the tradition, earning a degree in music, and young Joe remembers “My uncle brought a mandolin down when I was nine years old and left it there, and I learned how to play it by the time he came back to visit, so he just gave it to me.”

Today, Joe is a polished mandolin player. As we talked, he picked up Tim’s mandolin and I borrowed Wayne’s guitar. Much to my surprise, he played three of Adam Steffey’s breaks from “Every Time You Say Goodbye” note for note.

Joe was born in Richlands, Va., in 1971. He says he has known Wayne Taylor “ever since I was little;” indeed, Wayne’s wife was young Joe Clark’s Sunday School teacher. However, in his teen years, you probably wouldn’t have figured him for a Sunday Schooler or a bluegrass guitar player. According to Joe, “I never fooled with it much till I got up into high school. I played in some rock and roll bands and stuff like that. Had the longhair. I did. I looked like a little Meatloaf!”

After high school, Joe moved to Detriot. “I worked in an auto parts store when I first moved there, playing music on the weekends. And then I quit that and got a job working in a factory, and I did that for a while. Then the music started dying, so I got tired of it and moved back here. It’s been better ever since I came back.”

Although he doesn’t “…claim to be a guitar player,” you couldn’t have proved it by his lead playing at the IBMA Showcase. He alternately ripped off blazing rides on up-tempo tunes and turned in bluesy interpretations on the slower numbers, showing the influence of his rock background. As Joe says, “It (rock ’n’ roll) gives you a lot of good ideas to put into bluegrass, as long as you don’t take it too far.” Joe is also very conscious of not slavishly imitating style leaders like Tony Rice: “I’m trying to get away from him, but on some licks, you can’t help it!”

Other instrumental influences include Bill Monroe, Doyle Lawson and Sam Bush. In a band context he prefers “that good, bluesy, driving stuff, like the Lonesome River Band. I like that, and Alison (Krauss), of course…” As far as his role in the Tim Laughlin Band is concerned, Joe is straightforward: ‘Well, as a unit, I just try to fit in, make it all work, and not try to play against the others. We just want to tighten up as a band.” And, he has no problems playing music full-time: “Oh yeah. As long as we can get the shows and people want to book us.”

That probably won’t be an issue. The band has several festivals booked for next year already, and with an impressive Owensboro Showcase under their belts, the prospects look better than ever. This is a talented band ready to work. As Tim says, “…I’d play every day if people would have us.”

So, beyond working as much as humanly possible, what are the goals of this new organization? The first might be to develop a unique sound. That drew a unanimous response from the band when I first interviewed them. Wayne spoke for the others: “I’d like to think when somebody hears this band, when they hear a song on the radio or something, automatically they say, ‘That’s the Tim Laughlin Band.’ They don’t listen and say, Who is that?’ And I think if you can accomplish a little of that…” Then you’re definitely heading in the right direction.

Tim Stafford, former guitarist with Alison Krauss, lives in Johnson City, Tenn., with his wife and son. He is an IBMA board member and chair of the organization’s “Bluegrass In The Schools” committee. Currently, he teaches part-time for the history department of East Tennessee State University but he’d like to pick some more.