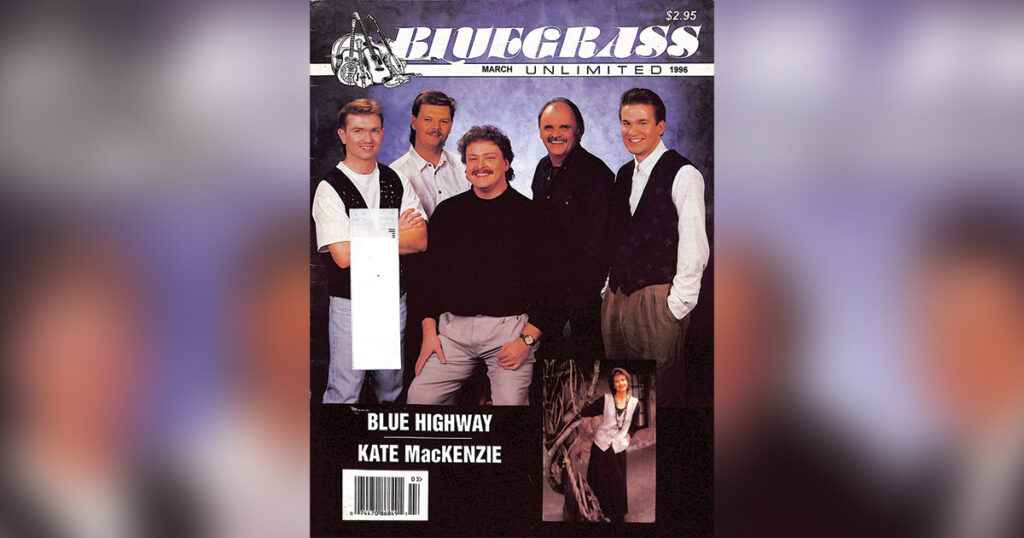

Home > Articles > The Archives > Blue Highway — It’s A Long, Long Road

Blue Highway — It’s A Long, Long Road

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

March 1996, Volume 30, Number 9

The arrival of a significant new band in bluegrass is always a momentous event. When one does appear with the clear potential to become a major player, it is absolutely fascinating—as well as great fun—to watch. Few bands indeed have the combination of utterly crisp timing, vocal prowess, top quality new material, and a sound that is both compelling and unmistakably their own. Blue Highway has it, and already there are lots of folks paying close attention.

Bristol Tennessee/Virginia’s elegant Paramount Theater is filled with energy and anticipation. The East Tennessee State University Bluegrass Band and the Stevens Family have just concluded their sets to excited and enthusiastic applause.

Blue Highway—fresh from an 8500-mile trans-continental tour to promote its new Rebel album, “It’s A Long, Long Road”—takes the stage. Starting with the opening notes, the Paramount audience senses something powerfully unique about this band, and responds with ever-increasing fervor as the set proceeds. By the end of the evening the crowd has repeatedly risen as one to deliver prolonged and thunderous standing ovations.

Blue Highway’s magnetism and intense audience rapport does not depend on gimmicks, flash, or packaged showmanship. It proceeds, rather, from a breathtakingly pure musical excellence and engagingly spontaneous good humor and wit.

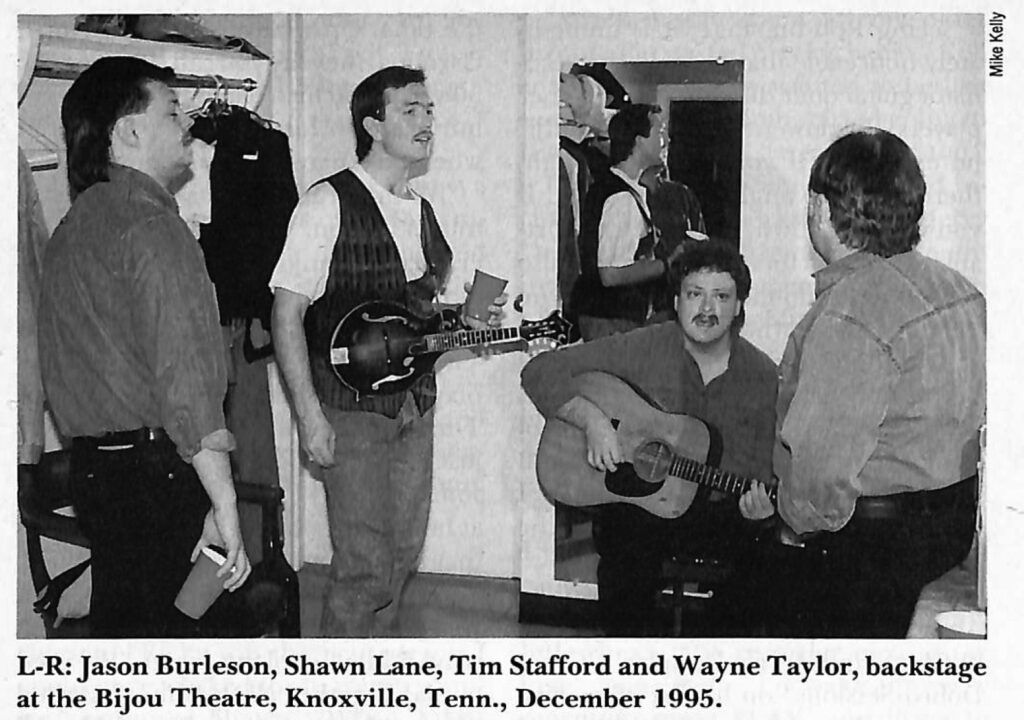

The band consists of Tim Stafford, Rob Ickes, Shawn Lane, Wayne Taylor and Jason Burleson. Already they have impressive achievements to their credit. Among these are three Grammy-winning albums (Tim Stafford for “Every Time You Say Goodbye” with Alison Krauss and Union Station and Rob Ickes for “The Great Dobro Sessions” and “I Know Who Holds Tomorrow” with Alison Krauss and the Cox Family). Additionally, band members have toured/and or recorded with some of the most respected of today’s artists: Ricky Skaggs, the Cox Family, Larry Sparks, Doyle Lawson, as well as Alison Krauss.

Thus, these are—despite their relative youth—seasoned professionals who are at home playing the most prestigious venues in acoustic music—Carnegie Hail, Town Hall, Wolftrap, Winterhawk, the Strawberry Festival, the National Folk Festival, Telluride, the Ryman and the Grand Ole Opry to name just a few. Their television exposure is likewise impressive, including videos and major shows on TNN, CMT, PBS, and CBS.

The group’s current album, “It’s A Long, Long Road,” showcases a host of Blue Highway’s strengths. There are several excellent tunes written by Wayne Taylor and Tim Stafford. Wayne, Tim and Shawn are all highlighted for tire exceptionally strong lead singers they are, and their harmony vocals are likewise striking. Rob Ickes demonstrates that he is among the very top level of resonator guitar players in the nation, and Jason Burelson’s banjo (he also doubles on mandolin) has the rock-solid punch a great band needs.

TIM STAFFORD is among the most original and versatile guitarists in blue- grass as the countless thousands who heard him with Alison Krauss and Union Station are well aware. His earlier performing and recording experience includes the East Tennessee State University (ETSU) Bluegrass Band, the Boys In The Band, and Dusty Miller.

In addition to performing with Blue Highway, Tim works in a variety of ways to further the growth of bluegrass. He currently serves as the vice chairman of the board of directors of the International Bluegrass Music Association (IBMA) and is also the chairman of the organization’s Education Committee. He is an active member of Bristol’s Birthplace of Country Music Alliance. Most recently, Tim has joined the music faculty of East Tennessee State University’s Bluegrass and Country Music Program teaching banjo and advanced guitar.

Tim is a Kingsport, Tenn. native in the heart of the region which has produced and nurtured a remarkable number of major bluegrass talents. Despite this favorable geography, Tim remained blissfully unaware of his home area’s rich musical heritage until he reached high school, where he happened to hear some local players and became fascinated with bluegrass.

Since that time, Tim, who holds a master’s degree in history from East Tennessee State University, has developed his musical skills to an extraordinary level. He has written a number of excellent songs and tunes, two of which—“Farmer’s Blues” and “Canadian Bacon” are heard on “It’s A Long, Long Road.” Tim has also used his abilities to host a radio show (Bluegrass Heartland, WETS-FM, Johnson City, Tenn.) and to produce albums including “East Tennessee” (by the ETSU Bluegrass Band) and “Down Around Bowmantown” (various artists) for East Tennessee State University’s Center for Appalachian Studies, and Services. The album “Ric-O-Chet,” which Tim produced for the North Carolina band of the same name, won the group a spot on Rebel Records’ roster of recording artists.

Tim has written a number of articles relating to the region’s music. (One, “Rocking In The Cradle Of Bluegrass,” [BU, October, 1987] was quoted at length by Tennessee’s U.S. Senator James Sasser in the Congressional Record.) In addition to the recordings mentioned above Tim appears on “Evergreen: Mandolin Music For Christmas” (Cactus) and “Old Town” (Rebel) by Butch Baldassari, “Arkansas Traveler” by Michelle Shocked, and Alison Krauss’ platinum CD, “Now That I’ve Found You: A Collection.”

Along with fellow ETSU alumni Adam Steffey and Barry Bales, Tim’s fulltime music career began with Alison Krauss and Union Station. “You’re supposed to pay dues in this business,” remarks Tim in wonderment, “but somehow we started at the top. In 1988 Barry and I entered the SPBGM A contest in Nashville when we were in the Boys In The Band. Alison was there with Union Station which was also competing. That was the first time we met one another and heard each other play.

“A few weeks later she called me to offer me a job,” continues Tim. “I was shocked. I thought, ‘I must be doing something right.’ I didn’t know why she liked what we did so much. I couldn’t accept her offer at that time, though. Later Alison heard Adam, Barry and me with Dusty Miller at the Station Inn in Nashville playing to an audience of about five people, or so. She complimented our music, and, I think, bought a tape. In May 1990, Alison made another job offer, and this time Adam, Barry and I all accepted.”

Tim toured with Alison Krauss and Union Station until 1992. “I really did have a good time in that band,” says Tim. “Everyone had a good sense of humor, and you’ll never play better shows than Alison does.”

Union Station was maintaining a demanding schedule of more than 200 dates per year. One day, when he came in off the road, Tim’s new baby son, Daniel, didn’t recognize him and cried. Tim realized that he didn’t want Daniel to grow up with an absent father, and decided to stay closer to home.

“I just saw Alison’s schedule recently,” Tim remarks, “—one week off between June and September! I didn’t feel I had any right to mess up Daniel’s life, with that kind of itinerary.”

His desire to continue with music led Tim to organize Blue Highway. “I’m real pleased the way things have happened, he smiles. All five of us share so many of the same ideas about music, and everyone is so nice—easy to get along with.

“We had a ball when we did our album,” he continues. “It’s the most fun I’ve ever had—Shawn and Wayne’s duet singing came together so well. I think we’re playing to the band’s strengths.”

The creative part of music is important to Tim. “It’s great to be in a band with songwriters,” says Tim. “It’s such an advantage. I’m motivated like never before to write songs. All five of us wrote a new song, ‘Clear Cut,’ together at Shawn’s family cabin up in the southwest Virginia mountains. I played guitar and all five of us contributed ideas. It came together fast; in about three hours we had the song in final form. It’ll be on our next album.”

Many musicians cite strong influences from the preceding generation of players—usually the artists they heard when they first became interested in bluegrass. Rarely do they cite their contempories, particularly not those even slightly younger than themselves.

Interestingly, Tim speaks with unstinting praise of just such a contemporary, Ron Block, who continues to play with Alison Krauss and Union Station. “When Ron joined Alison, I thought I’d died and gone to heaven,” Tim recalls happily. “Ron is the most underrated player in bluegrass. It’s like Ralph Stanley meets Pat Metheny meets Eric Clapton meets J.D. Crowe, and he does it without playing a lot of chromatic stuff. Ron has solid-as-a-rock timing. I liked him ever since I heard him in the Weary Hearts.

“Ron has great practice habits,” explains Tim, “and his work ethic is incredible. He’s always practicing, always working to make his music better. On tour, Ron would use a drum machine track in the van or —later—on the bus. He’d play 60 minutes of drum tracks— the greatest hits of drum tracks,” laughs Tim. “At night he’d always practice—sometimes 7 or 8 hours. He was so focused. He’d make a list of what to practice—like he was his own music teacher.

“Ron Block’s musicianship contributed in a major way to the band’s musical standards,” asserts Tim. “Now when I sit down to practice, I’m more focused. The results are obvious when you know just what you want to accomplish.”

SHAWN LANE plays fiddle and mandolin with Blue Highway. He was born and raised in rural Ft. Blackmore, Scott County, Va. The southwest Virginia homeplaces of Carter and Ralph Stanley, Jim and Jesse McReynoids and the A.P. Carter Family are all close by. Kingsport, Tenn., is the closest-city.

“Quite a few people like bluegrass where I grew up,” recalls Shawn. “Actually, I liked some pop stuff, some country and some rock and roll.”

Shawn was fortunate to have considerable encouragement from his family early on. “My granddad showed me some things on the fiddle,” he explains. “My uncle Ronnie and my great uncle played two guitars and I played fiddle. Wasn’t no singing went on in it. We just, played fiddle tunes. We called that a band—the Dry Hollow Boys.

“My Dad took my brother Chad and me to pig roasts.” continues Shawn. “The guy who ran them would charge people $3 a head. As kids—8 or 10 years old—he’d put us on stage. If you could play any at all, people would just go crazy over you. They’d pass the hat around. That was fun—it really sparked me. It made me think ‘I wonder if there are people who do this all the time and make money at it?’ ”

Shawn had one formal lesson with a Wisconsin-born fiddler named John McCutcheon who had moved to Scott County to learn authentic Appalachian styles from regional musicians. (McCutcheon had became a favorite at local musical venues like the A.P. Carter Family Fold. He later became a highly successful recording artist with a nationwide following.)

“John McCutcheon,” says Shawn, “helped me a lot, really. I was doing some things wrong in my playing. He showed me some position type things on fiddle that I hadn’t known. I didn’t have anybody to show me those things—I’d just listen to records and try on my own to figure them out. You can ruin yourself like that a lot of times, doing stuff the wrong way, and then you can’t learn it right. I spent hours just sitting around listening.”

One of Shawn’s early friends was another Scott County native, Marcus Smith. Later, at East Tennessee State University, Marcus would play in the ETSU Bluegrass Band. He subsequently toured with Larry Stephenson and Lou Reid, Terry Baucom and Carolina, playing on the latter group’s highly successful albums “Carolina Blue” (Webco) and “Carolina Moon” (Rebel).

“Marcus and I were about 14 when we got together,” says Shawn. “Marcus sang lead, and I sang tenor. Then I started singing some lead here and there. We sang at the Carter Fold and for six or seven years we went to the Union Grove (N.C.) Fiddler’s Convention and competed. We’d win sometimes and lose sometimes.”

Shawn’s first real band was also with Marcus. It was called Blue Ridge and included local musicians Tommy Freeman and James Alan Shelton. (James went on to become Ralph Stanley’s lead guitarist.) “We just played local stuff,” recalls Shawn, “and one time at (the Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver Festival in) Denton, N.C.

It was through Marcus that Shawn was able to join the East Tennessee State University Bluegrass Band for a tour to Russia—eight performances in eleven days. “Marcus told me about it,” grins Shawn, “and I said, ‘Wow, that’d be something to go over there.’ I’d never been far out of Virginia at that time. I’ll never forget that. That was just before the fall of communism in Russia.”

Shawn got to know another member of the ETSU Bluegrass Band, Kenny Chesney (now a highly successful BNA country recording artist and songwriter). “It really struck us the way the Russians enjoyed our music so much,” reflects Shawn. “It seemed that anything you’d do they would just soak it up—like they were starving for it. Like when Kenny, Marcus and me just out in the dormitory hall goofing around singing Elvis songs. The Russians—they’d be glued onto you, like they were starving for it. Well, I guess they were starving for a lot of things,” he concludes. “It was an experience, I tell you.”

The ensuing years brought Shawn a dizzying array of professional opportunities. He played with the Lou Reid Band for a year (part of the time with Marcus), and recorded on fiddle with Larry Sparks on his “Travelin’ ” album. Next Shawn sang and played fiddle and guitar with Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver for nearly two years, singing and playing guitar on the album “Hallelujah In My Heart.”

Shawn’s subsequent job was a year on mandolin and guitar with Ricky Skaggs, who had the highest praise for Shawn’s singing. “Ricky was the best person I could have worked for in country music,” enthuses Shawn. “When I was singing with Ricky I didn’t have to worry about him. I just had to worry about me. He was always there with superhuman singing—and pickin’ too. He’s always been that way. Never has been lacking anything. He just tears it up!”

Shawn is clearly elated about Blue Highway. “This is something that everybody’s on the same channel on,” he declares. “I like to pick with good all- around people. Not just good players, but good people too. All these guys want to play the same kind of music. It just seemed to fall together. I don’t know what caused it—it just happened.

“I really like that we have a lot of well-written songs that no one’s heard before,” he goes on. “I know as a fan that I like to hear songs that haven’t been sung before. Good material is hard to find. If it wasn’t for Wayne and Tim writing songs, I don’t know where we’d find new material. I hope as I get older I can write some good songs.”

ROB ICKES, Blue Highway’s resonator guitarists, grew up a continent away from Tim and Shawn, in Millbrae, Cal.,—a very urban suburb of San Francisco. Unlike Tim—but like Shawn—Rob was surrounded by music from the beginning. His grandparents played fiddle and accordion. “The whole family played fiddles and guitars,” recalls Rob. “I was supposed to be a fiddler. Grandpa gave me a fiddle, but I never stuck with it.

“When I was about 12 my older brother Pat started playing banjo,” Rob continues. “I really wanted to be like him. He and my Mom started going to festivals and then I started going, too.” One festival the family attended included a dobro workshop with Jerry Douglas. While Rob remembers it, nothing about it was a major impression on him. And yet riding home in the family car, the musical event occurred that determined the future course of Rob’s life. “My brother was listening to a tape of Mike Auldridge’s first album,” recalls Rob. “I still remember the song— ‘Tennessee Stud.’ “I said, ‘What’s that?’ I just liked the sound so much—I became infatuated.

“From then on at home I’d put my little cheap tape recorder next to my bed,” grins Rob. “I’d wake up every morning, press PLAY, and listen to Mike Auldridge over and over.”

In time, Rob developed an appreciation for other players. “I love the ‘Foggy Mountain Banjo’ album with Josh Graves,” says Rob. “Later I got into Jerry Douglas and started emulating his stuff. Brother Oswald too—I had tablature for his version of ‘End Of The World’ and ‘Sailing To Hawaii.’ ”

Rob listened to albums by the Seldom Scene, noticing Mike Auldridge’s backup and then to the vocals and the whole band sound. “Then I discovered Tony Rice and Ricky Skaggs,” explains Rob. “At the time I didn’t know what drew me to them. Now I know it was rhythmically more exciting. There was a certain rhythmic energy and tightness that I hadn’t heard before.”

Rob offers a few observations about the distinctive way he plays. “I got my left-hand position and the way I hold the bar from trying to make the instrument sound like Mike Auldridge’s recordings,” says Rob. “It came naturally. In fact I really never thought about technique until a few years ago.

“Since then, I’ve really been working on my right-hand technique,” he continues. “I used to move my hand around too much, and it affected my timing.

“If you watch Earl Scruggs play banjo, it’s so smooth—no excess movement at all,” observes Rob. “Now I try to pick from my fingers—I used to move my whole hand sometimes. Actually, I still do that occasionally if I want to hit a note really hard.”

Seeing Rob on stage, it is immediately noticeable that he holds the resonator guitar quite different from other players. “I’ve lowered the [instrument],” he explains. “If you’re playing high, there’s a sharp angle on your wrist. If you’ve got it down, it’s more comfortable. Tipping it forward at an angle also relaxes the hand more. My muscles no longer get sore when I practice rolls.”

Regarding Blue Highway, Rob is predictably enthusiastic. “I love this band,” he smiles. “This is just the kind of thing I’ve been waiting to sink my teeth into. It’s something I can give a lot to. I really like the way everybody plays to the song. It’s not a hotshot thing at all.”

With two Cox Family albums, one by Alison Krauss and the Cox Family, Ric- O-Chet, and Jerry Douglas’ “Great Dobro Sessions” on his list of credits, Rob is well on his way to widespread recognition as being right up at the top of his field. This, however, does not mean that life has become easy.

“I’m not getting rich at all, but I’ve been scratching by,” says Rob. “I’ve never been into money. College (at Davis University in California) was good for that, because it taught me I could live on my own without that much money.

“I just got married last summer,” he goes on. “My wife, Jennifer, has always been supportive of what I do. There’s a lot of artists in her family—visual artists. That made it nice for her parents, cause they’re used to dealing with starving artists,” laughs Rob. “Jennifer plays piano really well, but she feels that because she can’t improvise, she’s not good. Of course, that’s ridiculous.”

“I’m really happy right now,” concludes Rob. “There’s something about the suffering and the giving to it that comes out in your music. It makes you stronger.”

JASON BURLESON grew up in Newland, N.C., not far from the East Tennessee border. “Newland’s got just two red lights,” volunteers Jason. “Everybody knows everybody else. It’s high enough to grow Frazier Firs. Selling them for Christmas trees is the biggest thing. Sugar Mountain in Banner Elk nearby has ski resorts. I worked as a ski lift operator one winter over there.”

“Jason is a super musician,” observes Tim Stafford. “He amazes me more all the time. Up where he lives in North Carolina, they say you can throw a rock 30 yards and hit a banjo player. Lots of musicians in his area have wondered when he’d play with a national band.” “All my grandparents played,” volunteers Jason. “Both my grandmothers played banjo—not clawhammer—more like two-finger style. They played things like ‘Cluck Old Hen’ and ‘Groundhog.’ My one grandmother played one called ‘In There Rabbit.’ They didn’t have records. I think it was just passed it along from friends and some of their kinfolk. They just played at home, or maybe when some friends that played came over.

“There was this friend of mine, Alan Johnson, that lives in Newland that plays fiddle,” explains Jason. “We used to play together all the time. I started playing banjo when I was 11. All through the years we hung out and picked together. I had a cousin that kind of got me started out. His name was Jeter Griffith. I took some lessons from him on banjo for about a month. I played it for three or four years, and then got started playing guitar and mandolin. About three years ago I got back onto the banjo.

“For a long while I hadn’t heard anything but the old records of Flatt and Scruggs,” Jason recalls. “Then I got the first album by the Bluegrass Album Band. That was the first thing I heard besides the real old stuff. And I remember hearing Tony Rice’s guitar break on “Blue Ridge Cabin Home” and I really didn’t even know it was guitar at the time, but I thought, ‘Well I’m going to have to try to learn to do some of that.’ ”

In recent years Jason has worked playing banjo at resorts during the summer, including the nearby Tweetsie Railroad, and Dollywood in Pigeon Forge, Tenn. “One of the good things about working at the theme parks is that you can make a good paycheck every week,” explains Jason. “I’d save enough during the summer that I didn’t have to do anything in the winter. You’re either making pretty good money or you’re not making anything, so you’ve got to save as you go along.” About Blue Highway, Jason says, “I like a lot of the original material we’re doing. I think it kind of sets us apart from just doing stuff that’s already been done. And it’s really good. It’s not just doing originals to be doing originals.”

WAYNE TAYLOR, is one principal reason that Blue Highway’s original material is so good. The songwriter, bass player, and singer was born and raised in the southwest Virginia town of Richlands, and has dreamed for decades of making music his livelihood.

“Back when I was a teenager I tried playing rock,” says Wayne. “Being a teenager, I thought it was cool, but it didn’t last long. I just wasn’t any good at it! Then in my early ’20s I started singing gospel music.”

During subsequent years Wayne sang with regional gospel groups, most notably the Christianaires and the Bluegrass Kinsmen. “These were part-time groups,” explains Wayne. “We didn’t normally travel long distances because everyone had a day job.”

“I drove a truck for about 18 years,” reflects Wayne, “up until about a year ago. But the economy in the coal fields is at a real low point right now. I’d worked for the same man for 15 years—and with him I could always get off work for anything to do with music. When that situation ended I had to make a decision about my career. It wasn’t too hard, because right about that time Blue Highway was in the building process. That made it easier to say, ‘I’m going to do the music, and do whatever I have to do in the meantime to keep my head above water.’ ” Wayne’s initial response to bluegrass belies the often-heard assertion to the effect that ‘If people would only listen to real bluegrass they would love it.’ “My dad had been a big Ralph Stanley and Bill Monroe fan,” explains Wayne. “I had all the respect in the world for them and appreciation of their music, but it didn’t make me feel that I wanted to do bluegrass music as my main musical outlet. Then a friend of mine said, ‘There’s this band I want you to hear.’ It was the original Seldom Scene—with John Starling and Tom Gray. I’d just never heard anybody do bluegrass the way they did it. It was just a record, but it changed my whole outlook. I’m still a big Seldom Scene fan.

“When I got to see them, I just, loved their stage show, and I got to playing a few of their songs—just for my own enjoyment. That was the turning point that got me really interested in bluegrass. I guess that doesn’t show in what I’m doing now, because Blue Highway doesn’t sound anything at all like the Seldom Scene. But that band got me to thinking, ‘Maybe there’s more to this music than I realize.’ From there I started listening to other groups like Doyle Lawson and Hot Rize.

“As to songwriting,” says Wayne, “I started out of necessity. I never thought I could write. I just got tired of doing other people’s material—just covering other bands’ songs. And it was real hard to get anybody to give you a good song. I guess every songwriter is looking for the best deal they can get—the best band to record their stuff.

“The Seldom Scene had a great influence on my songwriting. Also (country songwriter) Skip Ewing. It’s not like I copy their songs, but listening to them I get inspired to try to write.

“ ‘Lonesome Pine’ (Blue Highway’s first song to chart on the BU national survey) is just about our area—southwest Virginia, East Tennessee, western North Carolina. I think we live in one of the most beautiful places in the world.

“Then,” continues Wayne, “There’s ‘The One I Left Behind.’ It’s inspired by fact, but the story itself is fiction. Things just had gotten bad up in the southwest Virginia coal fields, and about the same time the family farmers in East Virginia started having a lot of trouble too. So it’s about two people, one from the eastern part of the state who had lost his farm, and the other from the western coal fields, who ended up in the same city. They somehow met each other and all they wanted to talk about was what they had left behind, all for the sake of just trying to make a living.”

One of Wayne’s most interesting songs is a historical epic of separation, betrayal and reunion. The song has the feel of a true narrative set in the pioneering days of his home region. “‘Before The Cold Winds Blow,’ he smiles,”—I’ve had a lot of people ask about that. I was driving down the road in my coal truck one day and I could see the sunlight—it was real bright and it was glistening on the rocks. The chorus line came to me:

And the river rolls on like an endless ribbon,

The sunlight glistens on the rocks below;

He can hear her voice in the rippling water.

Saying “Please be home, before the cold winds blow.”

“I built the whole song from that line. I had no idea that the finished product was going to be that type of story, set in a historic time frame or anything like that.

“I’ve thrown away a lot of stuff,” observes Wayne, ruefully. “Maybe a verse and chorus and I’d go over it and say, ‘Well that’s not even worth keeping—it’s not worth even trying to finish.’ And there’s some of that stuff I wish I’d laid back for a few months and worked on later. Now I think, ‘Maybe there was a song there, but I just didn’t have a grasp on it right then.’

“Finding good material is probably the biggest challenge a band faces,” Wayne asserts. “I’ve heard some really good bands that didn’t have good material to showcase their ability. You have to define your own sound. It still has to be in the realm of bluegrass, but it has to be different from what everybody else in the world is doing. Knock wood, I think we’re on that track.

“I played electric bass for about 10 years,” says Wayne. “I’d never had much experience with acoustic bass before Blue Highway. It’s a monster!” he laughs. “I’ve heard so many people who just didn’t have a grip on it at all. And then I’ve listened to Barry Bales and Roy Huskey, Jr.,and Mark Schalz—people that I consider to be really good bass players.

“The one person in my life who’s making it possible for me to do this, Wayne concludes, “is Sharon, my wife. She is so supportive. She has a good job, and she’s willing to work and give me this opportunity. We’ve been married 17 years, and she’s known ever since I met her 20 years ago that I’ve always wanted to do something with my music. I’ve seen a lot of musicians who didn’t have that kind of support at home, and it really means a lot to me. The only thing she regrets is that she can’t take time off work to go with us when we tour!”

There are, of course, no guarantees of success in the difficult and unpredictable world of professional bluegrass music. But if ever there were a band that deserves to be widely heard and appreciated for its members’ ability, musical vision, and willingness to work hard, it is hard to imagine a better candidate than Blue Highway.

Blue Highway Milestones:

It’s has been just a year and three months since Blue Highway played its first date. The band’s achievements in that short time are truly remarkable. They include:

- Blue Highway’s debut release “It’s A Long, Long Road” (Rebel), was the # 1 album on the Bluegrass Unlimited National Survey (airplay) for three months, December 1995, through February 1996.

- The album’s title song, “It’s A Long, Long Road,” composed by Jack Tottle, occupied the #1 position on the same national chart in February 1996. The survey showed two additional songs from the album, “In The Gravel Yard” (#4), and Wayne Taylor’s “Lonesome Pine” (#9) among the top ten.

“It’s A Long, Long Road” placed #3 on Bluegrass Now magazine’s national survey of album sales for November/December 1995.

- “In The Gravel Yard” appeared on a CD included with the September 1995, issue of New Country magazine, along with Hootie and the Blowfish, Sawyer Brown, and others.

- Blue Highway was featured in two recent segments of the Nashville Network’s TNN Country News. The January 1996, appearance focused on the group’s upcoming second release (see below).

- “Wind In The West,” Blue Highway’s second album, is slated for release by Rebel Records in late April or early May. Recorded at Suite 2000 and Abtrax Studios in Nashville with engineer Rich Adler, it includes seven of the band’s own originals, including the title cut composed by Shawn Lane. An advance two-song CD will be sent to radio stations, and a cut is slated for a second New Country magazine CD release. A video is likewise planned.

Jack Tottle is Director of the. East Tennessee Stole University Bluegrass and Country Music Program, Department of Music anil Center Tor Appalachian Studies and Services, Johnson City, Tenn.