Home > Articles > The Archives > Expanding the Horizons — Susie Monick and Tony Trischka

Expanding the Horizons — Susie Monick and Tony Trischka

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

December 1976, Volume 11, Number 6

While there are plenty of lightning-quick banjo pickers around, only a handful have directly contributed to the stylistic development of the instrument.

Earl Scruggs, of course, is the giant in the field. Scruggs took the raw style he picked up in North Carolina from Snuffy Jenkins and others, refined and honed it and turned it into his own, which became the standard for every five-string banjo player to learn and follow. Others, like Bobby Thompson and Bill Keith, built upon the Scruggs style, making it even faster and more melodic. Don Reno, (also influenced by Snuffy Jenkins) meanwhile, added his unique two-finger and flat pick style to the banjo repertoire.

All these major innovators, however, have developed their banjo styles strictly within the bluegrass vein. But in recent months new albums have been released by two banjo players who are interested in expanding the horizons of the instrument and the types of music they can play with it.

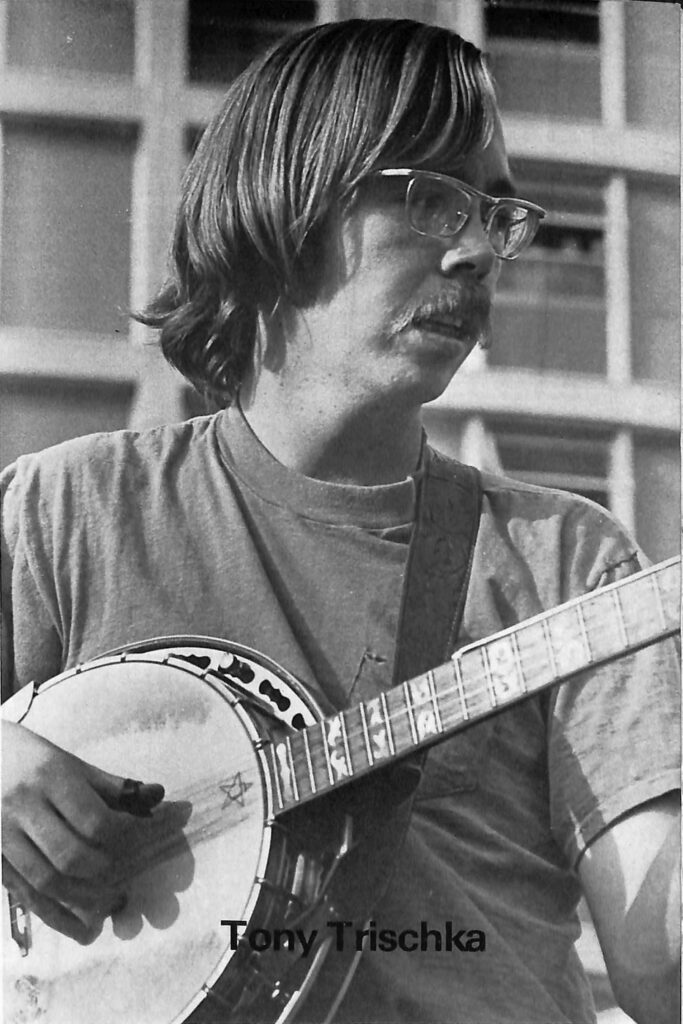

The inventive music of banjo players Tony Trischka and Susie Monick goes far beyond the liberties with traditional forms taken by groups in the so-called “newgrass” category. Although Trischka, formerly with Country Cooking’ and Breakfast Special, and Monick, the banjo player with the Buffalo Gals, have both been closely associated with newgrass bands, their solo work, while still based in bluegrass, sometimes leaves it entirely for spacey excursions into rock, reggae, be-bop and other forms of jazz. “We play banjo music that’s outside of any sort of mainstream,” Trischka admitted. “It’s just wacko banjo music.”

Trischka can play straight-ahead bluegrass with the best of them, but he gets tired of it. “Bluegrass uses the same old formulas, which is fine—you need that strictness to keep the strain going,” he explained. “But I wasn’t born in North Carolina 50 years ago, and most of the time bluegrass doesn’t have deep emotional content me. To me, it’s borrowed music, and I’ve got to play my music.”

Trischka’s music—and Monick’s as well—is clearly a combination and reflection of the banjo music he is trained to play and the rock, jazz, Eastern, Latin and classical music he likes to listen to. Thus, while his instrumental influences come from Scruggs and Keith, his musical influences are drawn from everything from Bill Monroe to contemporary jazz artists like John McLaughlin, Chick Corea and Stanley Clarke. Especially important to Trischka is the sound of the saxophone, and some of his music tries to approximate the screams of frustration with which players like John Coltrane and Eric Dolphy blew apart the jazz world 15 to 20 years ago.

“Playing banjo music with that heavy jazz influence just seems natural to me.” said Trischka, 27, a native of Syracuse, N. Y., and a graduate of Syracuse University. “I listen to jazz, rock and classical music more than I listen to country and bluegrass and that’s the kind of music I want to play. I don’t play saxophone or violin—I play banjo, so I do it with that.”

Like Trischka, Monick is interested in eliminating the stereotype of the banjo being used solely as a bright-sounding, rhythmically driving bluegrass instrument. “A lot of banjo players are into style; I’m into concepts,” said the 24-year-old member of Buffalo Gals, an all-woman bluegrass band also from Syracuse. “I want to take the banjo into new areas—to make a song like ‘Cripple Creek’ reggae, or classical, for example. I try to think of a tune as a wholeness, and take into account the interaction of the banjo with other instruments to create an entire setting.”

“Melting Pots”, Monick’s debut album on Adelphi Records, has her playing frailing banjo, five-string acoustic banjo and her new instrument, a five-string Ruby solid-body electric banjo, in a variety of muscial settings ranging from breakdowns to be-bop. “The banjo was used as the catalyst for the album,” she explained, “in that all the tunes were conceived on the banjo, but brought out as a total concept in conjunction with the other instruments.” The liner notes to “Melting Pots” proclaim: “This album is an example of musical philosophy based on fusion—people of different musical backgrounds and ability playing together and making good music—the banjo integrated into different kinds of musical expression.”

Monick feels the album, recorded in New York City in fall 1975, was put together with “inspired looseness,” which differentiates her music from that of Trischka, who was her first banjo instructor. “Tony is a genius at composition,” she said, lounging on the waterbed in the Syracuse apartment she shares with two of the other Buffalo Gals. “My album is more improvisational.”

Monick was aided on the project by several musicians who had become her friends during the Buffalo Gals’ past two years of touring the East Coast. The fact that they came from a wide range of musical backgrounds only served to further her master plan.

“If you can arrange tunes so everyone can play what they’re familiar with, you can overlap different styles. And if you have the confidence it will work, it will,” Monick explained. “The jazz musicians, for instance, had just never been approached by a banjo player who wanted to try playing their music. A tenor banjo had been used as a rhythm instrument in Dixieland jazz, but to use a five-string banjo as the lead instrument in a be-bop tune was considered totally off-the-wall. I had the guts to try it.”

Some of the songs on the album, like Monicks “Marmalaid,” a bop tune arranged in 15/4 time, and “One Day on South Street,” an open-ended jazz improvisation written by Buffalo Gals fiddler Kristin Wilkinson that is reminiscent of the style of the jazz-rock Mahavishnu Orchestra, could firmly be classified as jazz, while others glide subtly between styles. For example, the album opens with Ralph Stanleys “Clinch Mountain Backstep,” which Monick jokingly calls “a backstep for Ralph Stanley (one of her banjo idols), a step forward for Susie Monick.” Her arrangement begins with an unadorned bluegrass opening, but then moves smoothly into a jazzy interlude with the guitar of Steve Burgh, the bass of Eddie Gomez and the flute of Jeremy Steig, all of who are well-known in New York Jazz circles (Burgh in country and rock as well). The flute, bass and drums (Richard Crooks, the drummer for Breakfast Special and Eric Weissberg’s Deliverance, is a dominant force throughout the album) then build up the tempo again, leading back to a bluegrass finale featuring Monick on banjo and Wilkinson on fiddle.

But although the album takes off in several different directions, with styles ranging from the increasingly popluar Jamaican form, reggae (“The banjo is conducive to reggae because it stresses the off beat,” Monick said ) to funky rock (“I wanted a banjo tune you could dance funky to, instead of square dance”) and includes jazz musicians like Gomez, saxophonist Richie Cole and multi-instrumentalist David Amram, the more traditional aspects of banjo music haven’t been neglected. “Traditional stuff is as good as jazzy stuff or funky stuff,” Monick said. “If it’s a good tune, it’s good in any style. I could have jazzed up every tune by sticking in more complicated jazz chords, which might be more innovative, but would also make the tune sound different—less melodic. And I love melodies.” Thus, the album includes songs like “Colt’s Creek,” a traditional bluegrass-type tune; “Whiskey Before Breakfast,” a tune played in the old-time trailing style; and “Wicked Witch Breakdown,” a standard breakdown except that it uses minor chords to achieve its desired eerie effect.

Perhaps the major innovation on the album is Monick’s use of the solid-body electric banjo, which was made especially for her by the Ruby Banjo Company of Toronto, Canada. The medium brown-colored instrument has a solid body with resonator, two electric pick-ups for better tone and an inlaid neck modeled after her Mastertone banjo. While an acoustic banjo is brighter sounding and more percussive, Monick feels the electric gives her a mellower sound with the added ability to sustain notes. “It sounds like a cross between an electric quitar, a banjo, an electric piano and a steel guitar,” she said. “I play a lot of slides and other licks on it that are non-traditional for the banjo.”

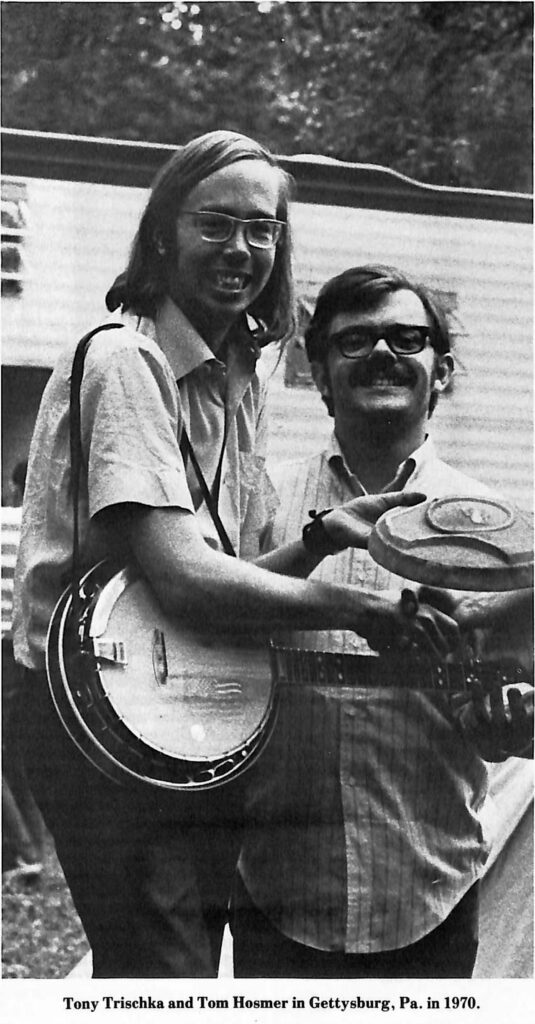

Until Monick arrived at Syracuse University six years ago, her only instrumental training had been a little bit of classical guitar—through high school in New Jersey, she had studied ballet. She picked up the folk guitar during her freshman year in college, and a year later started learning banjo a tune at a time from Trischka and an Earl Scruggs book.

“Now people say to me, ‘You’re not only good for a girl, you’re just good,’” she said in evaluation of her own playing. “Right now I’m more competent at writing than at playing, although my feel is definitely getting better. My technical ability isn’t that far out yet; I’ve got a lot of development to go. But the songs on the album were at a musical level I could deal with. I played my licks pretty straight, but arranged them in a setting that was different. In the studio I held my own, but I’m nowhere near as technically advanced as Tony.”

Trischka has been playing guitar and banjo since high school, and his two albums on Rounder Records, “Bluegrass Light” and the recently released “Heartlands”, place more emphasis on composition and his own virtuosity on the banjo than Monick has done on hers. “My first two records are potpourri,” said the humble, soft-spoken Trischka, who is considered a musical genius by the other musicians in his home area and elsewhere. “They’re maverick-type records, from out of left field. If anyone has listened to all my playing from Country Cookin’ onward, they’d hear a natural progression, but if you heard it from out of the blue, it might be hard to find a basis for the music.” Trischka operates on the musical philosophy that “not everything I do may make sense musically, but if it works for me, it’s valid.” “The Theory (which he says was instilled in him by Andy Statman, the mandolin and saxophone player in Breakfast Special, who also strongly contributes to Trischka’s solo albums) is that there are basically no wrong notes, as long as you play in the right time and are convincing about it,” he explained.

“Now, if I were playing with Bill Monroe, there are obviously notes I could play that wouldn’t fit,” he qualified. “But in the kind of music I play, the musical boundaries in my head have broken down so much that more notes sound right to me than used to. When we start playing, we really don’t know what we’re going to play until we get there. You’re throwing yourself into a void and grabbing notes while you’re falling. It doesn’t always work—sometimes you fall.”

With cat-like agility, however, Trischka most often lands on his two feet. Whether moving the banjo into new modes, like the jazz-rock “Slapback” and the Latin-tinged “Sage Age”, or playing a flat-out breakdown (“Pike County Breakdown”) at an incredible speed, Trischka remains in total control of the music being made around him, no matter how far the music may get from the mainstream. His music never loses the banjo’s basic quality, its rhythmic drive, and adds to that unique and intriguing sense of melody. It is complicated to listen to, but ultimately rewarding when thoroughly digested.

And lest anyone think Trischka is just a weirdo who has deserted his bluegrass roots, on his next album, which will be called “Banjoland”, one side is devoted to a session he did at Nashville’s Starday Studios with Bill Keith, Vassar Clements, David Grisman, Tony Rice and Buck White, playing standards like “Dixie Breakdown” and “Salt Creek.” “People will see me playing with these guys and say that I must be all right,” Trischka chuckled. “It gives me legitimacy, I guess, but that was strictly an afterthought. We just all happened to be in Nashville working on another album, and I had the chance to do it. I don’t have the bluegrass solidity that they have, and it’s nice to be able to play in that context.”

On the other side of that third album, already recorded at Pyramid Sound in Ithaca, N. Y., where he did his first two albums, will be some of Trischka’s more recent acoustic and electric compositions, and he’s already at work composing for his fourth album, one side of which will be an orchestrated work using drums, electric instruments and a string quartet.

It’s obvious that Trischka, now playing in the Broadway bluegrass musical, “The Robber Bridegroom”, and Monick, who did some of her solo work at the Philadelphia Folk Festival in August, won’t be content to either play or compose banjo music that can be easily categorized and tucked way into one small musical cubbyhole. Both are interested in expanding the musical horizons and audience of their instrument, the banjo. They’re willing to experiment and take chances, and even if they don’t succeed immediately, at least they’ve taken the risk.