Home > Articles > The Tradition > A True Gentleman

A True Gentleman

The 86-year-old didn’t play music as a child, but picked it up a little later in life. In 1959, after a stint in the Navy, he came to Danville, Virginia, and decided to take up music in his spare time. “Old friends that I went to school with were plunkers. I wanted to be a plunker too, so I went to a music store on Union Street in Danville and bought a little A-40 Gibson mandolin. I learned two or three chords so I could play a little rhythm. While sitting in with these boys, they were to play a dance, but they didn’t have a bass fiddle.”

The Virginia native decided to try his hand with the doghouse. “I had an uncle who knew where one was in Rocky Mount, close to where he was raised up. He called it a trick. He said, ‘I know where one of them tricks are.’ He paid for it. It was a total of $50. I piddled around with it and one day he said, ‘I think I’ll come by and pick up that trick.’”

Mills had found his calling. He enjoyed playing the bass. “I said, ‘Let me get you $50 and I paid him.” He started playing out more. “The guys in Danville that I was playing with played a Saturday night dance. We didn’t know too much and suspected less than that, but it was fun.”

Mills played bass a while before he had a musical epiphany. “A fellow named Cliff Ragsdale was playing in Jim Eanes’s band. Jim was playing in Martinsville at the VFW on Saturday night. Cliff was playing Wednesday nights at a store. I carried my bass fiddle over there one night. He said, ‘Most bass fiddles have four strings on it, yours only has three.’ That was all it had on it and I don’t know any difference. It didn’t have an E string on it. He steered me in on that and I got more interested in it.”

So Mills started using four strings on the bass fiddle, but found it wasn’t always a requirement. “In later years in the ’60s, the Stanley Brothers came through Danville. They played the old barn dance. I went down and said hello. Homer Thompson was the radio personality and announcer. Carter said, ‘Homer, anyone around here that could knock a little bass with us?’ He pointed at me and said, ‘That boy right there does.’ Carter wanted to know if I wanted to play one with them. I said, ‘I’d love to.’ He said, ‘We got one in the trailer.’ I said, ‘I’ve got mine in the car.’ I was like Karl Malden (in the American Express commercials). Don’t leave home without it.

“I got it out. They were talking. Carter would turn around and strum a G chord and I’d tune the G string. They’d talk to someone else and then he’d strum a D chord and I’d tune the D string. Then they went on a little while and played an A so I tuned the A string. They went on and never did say anything about an E. He said, ‘We got a new tune. Would you like to go on and play it with us?’ He started playing a little ‘Wildwood Flower’ and said, ‘I think that’ll be all right.’ So if I could follow ‘Wildwood Flower’ then it was okay to play with bass with them, but you didn’t have to have no E string. Back then, the bass fiddle was a comedy thing like old Baggy Britches.”

Mills decided to become even more involved in music. “The music, in general, has always been of interest to me. Webster’s definition of music was ‘sounds that are pleasing to the ear.’ That’s it!” When asked when he became a professional musician. Mills humbly replied, “I don’t guess I ever was.”

Mills remembers, “Gene (Parker) approached me and said, ‘Let’s get together and play some grass.’ I said, ‘With who?’ He said, ‘There’s a fellow down at Laurel Park. He’s a pretty good guitar player.’”

Parker then suggested a young boy from Rocky Mount. Mills recalled, “He said, ‘He ain’t real good now, but I think he’s going to be a real good mandolin player. So what do you think about bringing him down?’ I said that would be good.”

Dempsey Young came and they clicked. Mills was pleased. “Things began to gel. The feeling of the music was good. Cable television was new in the Martinsville area where we lived. They were up and down both sides of the high rent district.”

Mills had an idea. “I boogied in there one day and said, ‘How about some bluegrass on your TV thing here?’ The man said, ‘OK. When you want to start? Thursday?’ I said, ‘Hmmm…let me get back with you.’ So we rehearsed with Roger Handy on guitar. Gene and I had played music together and Dempsey and Roger had played music together, but we had not played together as a band. We were going to do this Thursday night thing on cable TV, but what are we going to call ourselves?”

Their band needed a name. “I was coming home one night and I’m thinking, here’s a bunch of guys that played music, but that hadn’t played together. It was like being lost and somebody putting them together. Lost & Found! It seemed good. You couldn’t forget that. It’s in everybody’s newspaper every day. I told them that night. What about the name, Lost & Found? They said, ‘That’s the awfulest we’ve ever heard.’ I said, ‘Let’s use it Thursday night and we’ll come up with something else next week.’ And it never did change. We just went on and used that name. From that time on, Dempsey Young and Gene Parker set the tone for what Lost & Found would be for the next fifteen years.”

Banjoist Gene Parker had nothing but praise for his former band mate. “When I first met Allen, he was playing with the staff band at the Country T-Bird in Danville, Virginia. I liked Allen’s singing. He had a good voice. I told him, ‘Me and you need to play bluegrass.’”

The 81-year-old worked alongside Mills for 14 years (1973-1987). Mills discovered that making an album would put them on the musical road map. “In 1975, we recorded the first album with Rod Shively. He had recorded the Folk Life Festival at Ferrum College. He knew the ins and outs. Gene Parker was well acquainted with him so we talked with Rod about recording.”

Their album began to hit the radio waves in northern Virginia on WMAU radio. Through the week, Mills did body work. “I was sanding fenders. That was my day job. That album came out and Gary Henderson made arrangements for us to come to northern Virginia. To go to DC and play music, that was way out of the world! I hadn’t played too far from home til then.

“The audience feeds you. We got a little applause and we thought we were something! We were pretty much area musicians until I approached Dave Freeman. The first album we did with Rebel, we had recorded it with Rod Shively. I shopped it with Dave and he took it. That changed the whole perspective. You became accepted in other circles because Rebel was a very well established name.”

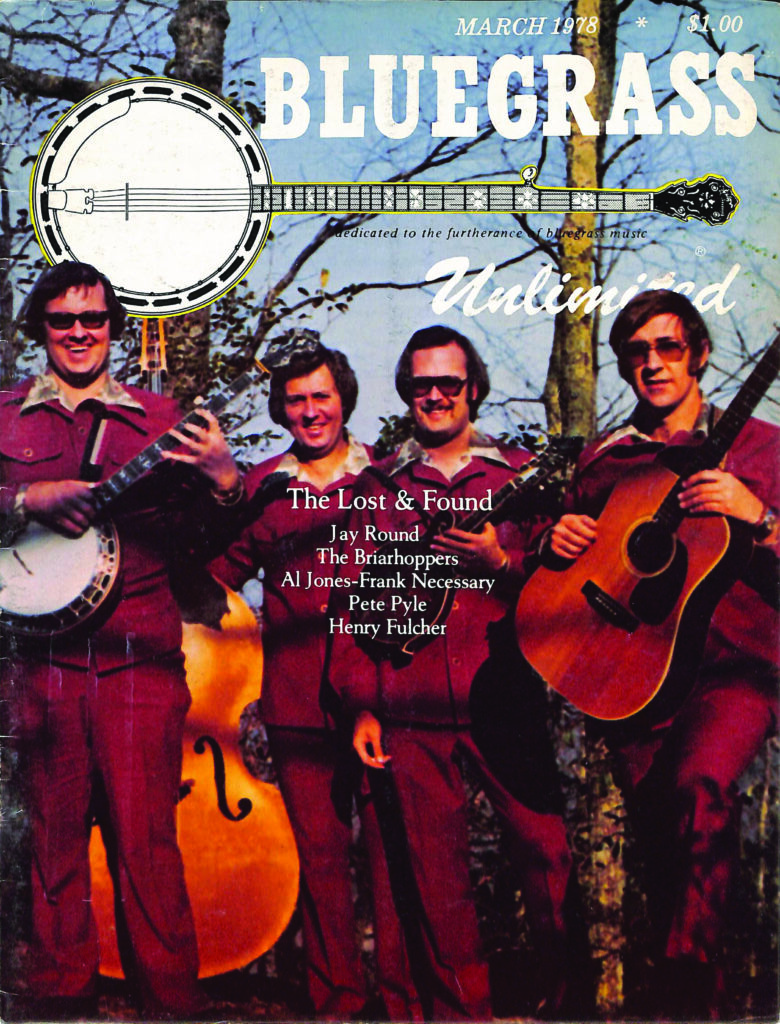

Lost & Found was Freeman’s inaugural group after his purchase of Rebel Records, even though they didn’t know it at the time. “In later years, we found out that was the first album Dave produced. He had bought Rebel Records from Dick Freeland. We call it the green album. It was self-titled; we’re wearing leisure suits on the front. Dave knew what to do to get the albums out for the radio stations. He was a good, solid gentleman in the music business. He knew the percentages and where they were selling was on the west coast. We got to thinking that maybe we should go out there and see if we could sell some. The sky was the limit so we kept reaching for it.”

Allen’s band started to travel. “We’d play somewhere on Saturday and then I’d come home and have to go straight back into the body shop. I’d work Mondays and Tuesdays, but a lot of times I didn’t get home until late Monday. I was in partnership with a feller in the body shop. I told him, ‘I’m not being fair to you. You’re coming in and doing the work. Let’s figure something out, a buy and sell agreement.’ We wrote down amounts and I think we were within $50 to $75 of the same figure. I told him, ‘I think I’m going to see what I can do playing some music.’ That was in 1977 when I decided to see what I could do. I figured that I could go back to trucking if I had to. I had done that in 1968 to ’72. I always had something I could do if I had to. You’ve got to have a prop. And behind every good musician, there’s a nurse with a good job. Deb (his wife) kept the lights on.

“We recorded albums in the years: ’75, ’76, ’78, and ’80. We started going here and yonder. We finally got to the point that we were making enough money that we didn’t have to call home to send us some money to buy gas. It was little by little. I guess some of our most requested songs were ‘Harvest Time,’ ‘Ida Red,’ and ‘Love of the Mountains.’

“I found out that you fall into one of two categories: you are either a creator or an imitator. So I tried to figure out how to put something together that no one else had ever done. That’s when I wrote ‘Love of the Mountains’. We were at some friend’s house and singing that. Bill Vernon (a Virginia radio announcer) asked, ‘Where’d you get that song?’ I said, ‘I wrote it’. He said, ‘Don’t sing that in public.’ I was thinking, ‘It’s mine, I can sing it if I want to’. What he knew that I didn’t was that I needed to copyright it to protect what you’ve got. The original version was recorded on Outlet Records in 1975. Lance LeRoy said once it goes in print, it’s there forever and you can’t change it. That’s the truth.”

A prolific songwriter, Mills has his own personal favorites. “‘Love of the Mountains’ was a tribute to my mother’s upbringing. My mother never knew her real mom because she was just 18 months old when my grandmother passed away in 1921. The old mountain way was that the grandparents would take the child and raise it. That’s how my mama was raised up, by her grandparents, aunts and uncles. They always called her Babe. There was a little bit of emptiness in Mama’s life. I could see it, but we never talked about it. That song is basically a tribute to her grandparents that raised her up, in my mind. That was something that I wanted to write about. It was the same thing for ‘Wild Mountain Flowers.’

“I have a lot of compassion for ‘Wild Mountain Flowers.’ That’s a song about some people that I knew in real life. A gentleman and a lady were sweethearts, but never married. They were active in a Pentecostal Church in Danville. I knew them both real good. I often wondered why they never married. The lady chose to live with her mother to take care of her in her twilight years. The young lady became ill and passed away of a brain tumor in 1954. The gentleman lived on, but never married. It was just a story of that. I told him that I wrote a song about you and Katherine and gave him an album.”

Allen married Deb, the love of his life, on March 16, 1979. Their union brought one daughter, Melody, and eventually, one grandson. Mills has two daughters from a previous marriage, Janet and Jeanne. He is proud of his family. “I have a 1959 model daughter, a 1962 model daughter, and a 1984 model daughter. That ’84 model was born on my birthday.

“We’d been out west and I had my first encounter with the telephone that didn’t have no wires hooked to it. We were in a Pizza Hut in the Minneapolis area. A fellow sat down with what looked like a cigar box. I said, ‘What you got in that box?’ He said, ‘A telephone’. I said, ‘How about calling my wife?’ He asked for my number and I thought he was kidding. He handed me a receiver and I thought he was just pulling my leg. I said ‘Hello’ and Deb said ‘Hello’. I said, ‘Deb, is that you?’ It was about 2 or 3 o’clock in the morning when I called her. I apologized and told her to go back to bed. She said, ‘I don’t think I’m going to carry this baby another month.’ I told her to be careful and that I’d be home on Monday. We didn’t have cell phones back then. I told Steve Thomas that today is my birthday, but I told him that he couldn’t say nothing about it. When I got home (the next day), it was kind of strange, there weren’t no lights on in the house. I looked on the table, there was a note that said Melody Rae got here last night. I took off and went flying over to Stuart to see that little thing over there. She wasn’t no bigger than a doodle bug. She was a month early.”

A true family man, Allen was also very close with his nephew, the late Jason Moore. “He was four years old when we got married. I saw Jason learn and grow into an outstanding musician. He was doing so good. You can’t question life, but yet you can. It just didn’t seem fair to lose him. He enjoyed music so much, the whole nine yards. I see him every day. Deb’s got his picture sitting right here (in the living room).”

Deb added, “A friend of mine from high school lives in Kentucky and sent me a video when Jason played the last night before he passed away. He was spot on that night and played his heart out.

“Another lady that I have never met before, that had never seen bluegrass before, took an awesome photo of Jason that night before he died and posted it on Facebook. I messaged her and asked if we could use it. She mailed a 5×7 in a frame with a little bass fiddle on it to Melody (my daughter), Mollie (Jason’s widow) and us. She said she’d never grieved so hard over someone that she’d never met before.”

During their tenure, Lost & Found played some impressive venues. Most of the time the band traveled by bus with Mills or Young at the wheel. Mills was also the chief mechanic. “Old bus would break down every once and awhile. You’d have to get out, do that and fix this. You’d sometimes take a coat hanger to fix something ’til you could get back home, then we’d fix what the problem was. I’d work on it all week, then take off again on Friday. It was still enjoyable. There’s still a bunch of people that we maintain friends with. I cherish the friendships. It’s priceless. The people that you make friends with over the years, you don’t forget them.

“Marvin Comer from near the Baltimore area, near the Delaware border, was a good friend that bailed us out one time or another. One time the drive shaft came out on the bus. I called him and he said, ‘Just go to bed and I’ll send somebody.’ We woke up to banging and said, ‘What the world was that?’ Them boys had done come and put a drive shaft in that thing and he never would let me pay him for it.”

On a few occasions, the ensemble flew to their concerts. “We’ve done this and done that, played here and played there. We played some big festivals in Michigan. We became friends with Tim White in Bristol. Loretta Lynn was there. He asked if we wanted to play. We were in Florida so we flew into Knoxville and Deb picked us up at the airport and took us to Bristol. We opened for Loretta. We did our normal thing and somebody wanted to know, ‘How did they get in here? Where’d they come from? What’s all this?’ I think maybe we upset the apple cart in some folks’ minds, but we held our own.

“One time we were playing in Florida. We flew into Chicago from Orlando, rented a car and drove to Bettendorf, Iowa, for a show and then flew back to Orlando, got up with the bus, and headed west.”

Mills never flew with his instrument. “You never fly with a bass fiddle. Somebody always had one that I could use. If you fly with it, you better buy it a seat and strap it in beside you in a big wooden case!”

It came as a terrible shock when Dempsey took his own life (December 2006). “Deb was working at the hospital in Rocky Mount. I was home. Deb and Gene Parker came to the house. I figured Deb’s car had broken down. They said Dempsey had shot himself. I said, ‘Not fatally?’ They said yes. Wind could have blown me away. That’s an experience nobody needs to go through. It was just devastating in every aspect it could be. You didn’t expect anything to happen like that. Who knows what’s in somebody else’s mind?”

Lost & Found endured and had various members over the years, but Mills was the mainstay. “Gene drove (the bus) some in the early days, but he really didn’t want to. In later years, Barry Berrier drove some for us. He bought my bus when I couldn’t perform anymore after four back surgeries and then a hip replacement on July 24, 2017. About the fourth or fifth of August, we played the Osborne Brothers’ Hometown Festival in Hyden, Kentucky. Dan Wells and Ronald Smith did the driving because I didn’t have the stamina to do it. I toyed with the idea of retiring. I wasn’t doing my part. Somebody had to carry my bass and amp. I had to have a stool to sit on. You had to hire another person to be your caddy. I had to make a decision to quit it. That kind of wound it up.”

True to his downhome personality, Mills remains good friends with all the former members of Lost & Found. “I keep up with my buddies. I’m proud of that. We’ve been real fortunate. Nothing lost, nothing stolen. I’m thankful for the goodness. We always looked at the positive things. It was an enjoyable time to go on stage to play music, to feel the rhythms like they should be. It’s a pleasure when you go on stage and you ain’t got nobody to worry about, but yourself. The rest of them are going to take care of it and you just hang on.”

Barry Berrier shared, “Lost & Found was my favorite of any band I have ever worked with because of Allen and the way he treated me like family. I learned a lot from him—everything from traveling the country over to remodeling buses. I never felt like I was going to work when I was headed to bus call…it was more like an adventure every trip. We had a good time and made memories for a lifetime. He sold me his tour bus when he retired. He comes and visits very often…not sure if he’s coming to see me or his bus!”

Gene Parker noted, “Allen was a motivator. He was real good with people and real good on stage, talking. He had a sight of where he wanted to take the band. If it wasn’t for Allen, there wouldn’t have been a Lost & Found. He did all the booking, contacting promoters, and the transportation. He did everything! He was the kingpin. He worked three or four times harder than the rest of us.”

Mills reflected, “Every person that I’ve run into, every show that we’ve worked, all across the United States, Canada and Europe, I feel close to every one of them along the way. They gave me something to do that I really cherished and loved. If I live long enough and don’t play music and sit down and get to thinking, it’s highly possible their conversations will cross my mind and I would be thankful for that and all the musicians that we’ve played up and down the road with.

“I had so much respect for Jim & Jesse. I had a chance to sit down in the bus with just Jim and tell him how much I appreciated their music, what they done, what they recorded. He would give me advice. I told him about it all and said I love you. I shared that with him before he passed away. I really meant that, same thing with Lance LeRoy. He booked us for the Opry. He called and said, ‘My boy, you’re on at 10:15. Billy Walker was the host. You just got to remember one thing. Hal Durham, the Opry manager, asked if they’re any good. I told him, they’re damn good. So you got to remember that you’re damn good.’

“I just love people and being around them. You learn so much from everybody. It’s just a good time. A quitter never wins and winner never quits. That’s so true if you love the music. You can go through programs to detox you from drugs, but there’s nothing that can be done to detox you from music. It won’t work. You’ve just got to have it. You can’t get rid of it and I don’t want to. It’s just in you. It’s a sharing thing.”

Mills concluded in his gentlemanly fashion, “I’ve cherished every minute. We’d go and work our tails off, but we’re still gratified. Like Mac Wiseman said, ’tis sweet to be remembered.”