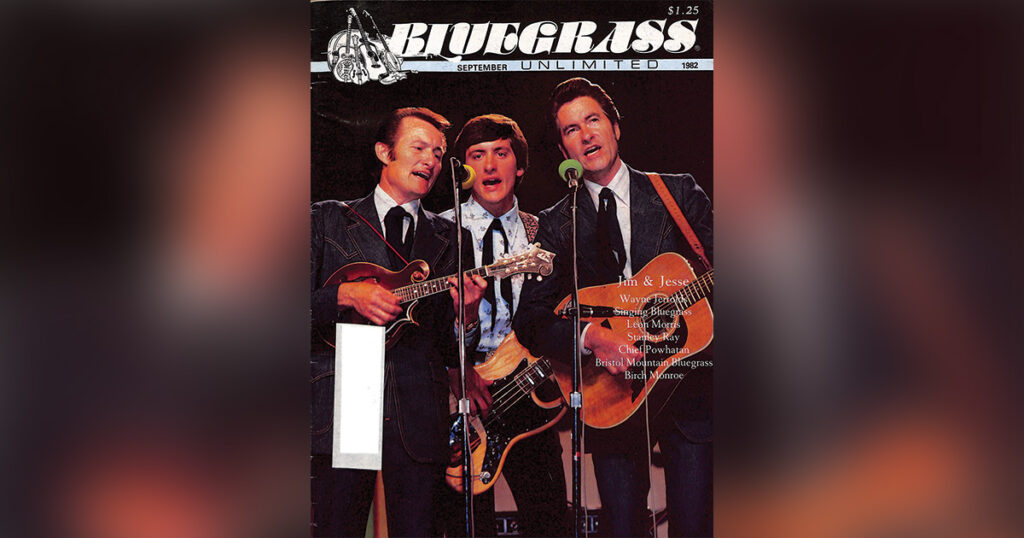

Home > Articles > The Archives > Jim & Jesse—Testing the Boundaries of Bluegrass Music (With A Little Help From Charlie Louvin)

Jim & Jesse—Testing the Boundaries of Bluegrass Music (With A Little Help From Charlie Louvin)

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

September 1982, Volume 17, Number 3

It is one of the great ironies of bluegrass music that one of its most consistently popular acts has also been consistently stepping outside the bluegrass mainstream. Throughout their career Jim and Jesse have stretched the definition of this music, have experimented with arrangements and repertoire, and have pushed at the outer limits of what is thought of as a narrowly-defined music form. The duo has recorded with such Nashville Sound producers as Don Law, Larry Butler, Frank Jones, Jerry Kennedy, Ken Nelson, Jimmy Bowen, and Billy Sherrill. The brothers have sung Nashville country tunes, trucking songs, rock ’n’ roll numbers, swing tunes, honky-tonk songs, polkas, Spanish-flavored ballads, and pop songs, and yet have met with universal acceptance among the most tradition-oriented of bluegrass fans.

“I think that a lot of the narrowmindedness that has been attributed to the bluegrass fans is really more from the die-hards and some of the promoters,” says Jim. “When we were doing the ‘Diesel On My Tail’ thing, for instance, the fans accepted it. They must have accepted it. The criticism we would get was mainly from other entertainers. There’s just something about the music business where if it’s successful there’s always somebody ready to knock it,” he adds. “Really, a lot of times it works like that. Even today,” Jim continues, “we hardly ever play an engagement where we don’t do ‘Johnny B. Goode’ or ‘Memphis.’ And they’ll normally stop the show. Now if the fans out there were that much against country, or even rock, it seems awful funny that they would love those songs in our show. It’s the same way with the Louvin’s country stuff we do.” “Yes,” volunteers younger brother Jesse, “ ‘When I Stop Dreaming’ is probably one of the most popular songs we do. Especially if we go to New York or Boston or up there, somebody will almost always come around and ask us to do some Louvin Brothers songs.”

That is Jim and Jesse’s way of introducing their next album project. For Nashville’s mainstream-country Soundwaves label the pair has teamed up with veteran hillbilly honky-tonker Charlie Louvin to form a pure-country trio. The music, as so many times before, tests the boundaries of bluegrass, but remains solidly Jim and Jesse in spirit.

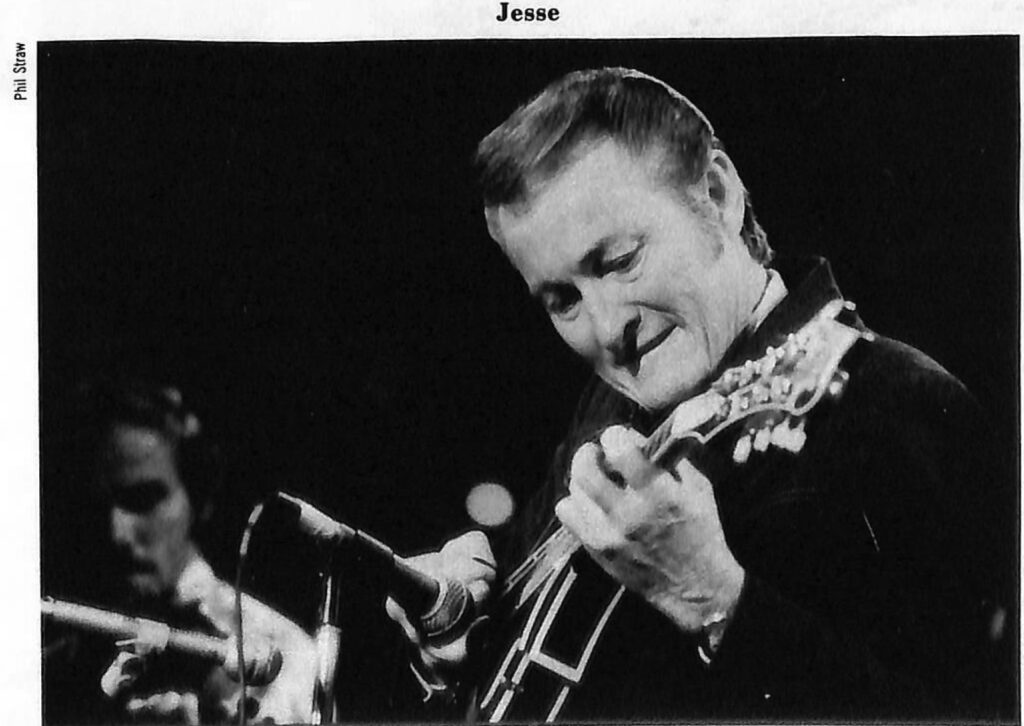

From the very beginning the McReynolds brothers made music their own way. They grew up quite near The Stanley Brothers, but did not fall as readily into Monroe’s pattern as Carter and Ralph. Jim and Jesse initially performed in a brother-duet, string band mode. The mandolin-guitar combination followed the style of such acts as The Blue Sky Boys, The Monroe Brothers, or any number of 1940s duets, rather than the instrumentation of the 1945 Blue Grass Boys. Jim’s tenor was smoother, softer, than the high lonesome sound of the classic bluegrass vocalists. Jesse’s astounding cross-picking virtuosity on mandolin transcended musical categories completely, but was probably the element in the brothers’ style that endeared them to bluegrass audiences in the early days.

Their first public recognition was as the winners of Best Duet at a St. Paul, Virginia amateur contest in about 1941. In 1947 they formed a four-piece string band with a fiddler and bass player for Virginia radio broadcasts. The five-string banjo was noticeably absent. In 1951 Jim and Jesse made their recording debut. Significantly, it was as members of an old-time gospel trio. Larry Roll sang lead in The Virginia Trio with Jim providing tenor harmony and rhythm guitar, Jesse singing baritone and playing mandolin, and Dave Woolum playing bass. The resulting Kentucky label singles from the Cincinnati-based Gateway Records firm are straightforward sacred singing with little of the urgency and drive associated with bluegrass music.

When Jim & Jesse arrived in Nashville to record for Ken Nelson and Capitol Records in 1952 they brought their banjo player Hoke Jenkins (Snuffy’s nephew) to the historic Tulane Hotel/Castle Studio downtown. The three were teamed with bass player Bob Moore, bluegrass guitarist Curley Seckler, and country fiddler Sonny James, later to become a Nashville singing star. This marked the brothers’ first recording with what could be described as a bluegrass line-up. Many of the songs from those sessions were written by Jim and Jesse, but the duo also recorded a version of Ira and Charlie Louvin’s “Are You Missing Me?” on the occasion.

Charlie Louvin entered the Jim and Jesse story again when Jesse McReynolds was drafted for the Korean War in 1953. “Me and Charlie were in the Service together in Korea,” recalls Jesse, “and we sang a lot together there. And when we came back to the States, the four of us worked a lot together.” This was the beginning of friendship and musical camaraderie that was to endure for 30 years.

Jim & Jesse performed, broadcast over radio, and starred in their own TV show in the Deep South states of Georgia, Florida (their home base then), and Alabama in the mid-1950s. This is when and where the brothers solidified their bluegrass reputation. Recalls Charlie Louvin, “When my brother [Ira] and I went down there to work with them, we found that it was basically their audience we had to work to. We found that they were against the electric guitar and we had one as a bass instrument. We never used a banjo. This was before bluegrass went ‘underground,’ ” says Charlie. Adds Jesse, “Take our experience together in Korea. Back then, it was all country music, hillbilly music.” “When they separated what they call The Nashville Sound from bluegrass music is when things really changed,” concludes Jim.

Things had changed, indeed, when Jim and Jesse returned to the studio to record their 1959 Starday releases. The McReynolds boys were prepared to evolve with the times, though, for one of the first things they did was record “Border Ride,” a highly-commercial Mexican-tinged Jesse instrumental. Comments Jesse of this period, “We tried to expand as we went along. We tried to do enough variety that we could be accepted on a country show, or on a radio show where they might have played Bill Anderson or any other Nashville act. That’s the thing we’ve always tried to do.” Jim remembers that, “In those days the only people that were really making any money with bluegrass music was Flatt & Scruggs. And they were doing it with television in the 1960s; it wasn’t through records.”

In 1961 their Columbia/Epic recordings began demonstrating just how far Jim and Jesse were willing to stretch bluegrass boundaries. The first LP to appear, “Bluegrass Special,” was billed as “country-style music-making” and was produced by Don Law and Frank Jones, architects of the infamous pop-oriented Nashville Sound. The second, “Bluegrass Classics,” was produced by Jerry Kennedy, who is much better-known for his work with The Statler Brothers, George Jones, and other mainstream country acts than he is for any bluegrass connections. The third, “The Old Country Church,” was a Billy Sherrill production of 1964. And 1965s “Y’All Come!” was a collection of country novelty tunes. It’s not that these albums had nothing to do with the bluegrass tradition. But their polished performances and the brothers’ willingness to work with mainstream Nashville producers illustrate that Jim and Jesse were still making music that did not necessarily toe the bluegrass line.

They tested the boundaries even further on their next release, “Berry Pickin’ In the Country/The Great Chuck Berry Songbook.” In 1967 came their most country-oriented effort yet, the “Diesel On My Tail” album, which included Hollywood’s “Ballad of Thunder Road,” Herb Alpert’s “Tijuana Taxi,” and Music City’s “Six Days On The Road,” “Girl On The Billboard,” and “Give Me 40 Acres.”

By the time “Saluting the Louvin Brothers” appeared in the late-1960s it looked like a return to the bluegrass tradition. Country music had evolved so much that the Louvins’ songs were by then becoming accepted as part of the traditional repertoire. But Charlie Louvin hastens to point out that “I’ve never had a communication with the bluegrass crowd. I’ve never been bluegrass. And my brother would have fought you in a second if you’d called him bluegrass.” Jim and Jesse’s record was the first time anyone, let alone a bluegrass act, had recorded a tribute to the Louvins; and it was largely through the McReynolds’ efforts that Louvin Brothers standards have been spread to bluegrass audiences.

In the succeeding years Jim and Jesse continued to record material from a wide variety of sources and styles. “Golden Rocket” came from Hank Snow. “Buckaroo” came from Buck Owens. “Maiden’s Prayer” is from Bob Wills’ repertoire. “Snowbird” was an Anne Murray smash. “Knock Three Times” and “Billy, Don’t Be a Hero” were pop- rock hits of the 1970s. “Fifteen Years Ago” came from Conway Twitty. “Love Is a Fading Rose” is from the pen of contemporary country composer Sonny Throckmorton. “Beer Barrel Polka” and “Bye Bye Blues” are, of course, pop standards. “Mansion On The Hill,” the Hank Williams honky-tonk standard, is as much a part of their repertoire as the swing-style instrumental “Under The Double Eagle.” A medley incorporating “America the Beautiful,” “God Bless America,” and “Battle Hymn of the Republic” surfaced on Jim and Jesse’s “Songs About Our Country” LP; and Jesse’s “Mandolin Workshop” collection of instrumentals included everything from “Rose Garden” to “Never On Sunday,” “Last Train To Clarkesville,” “Help Me Make It Through the Night,” and “Green Green Grass of Home.” The brothers’ sincerity of presentation and their consummate musicianship have made all these songs acceptable to bluegrass lovers. Few other acts in the field could have managed this feat.

As popular as they are on the bluegrass festival circuit, and as loved by bluegrass fans as they are, Jim and Jesse are continuing their habit of experimentation and innovation into the 1980s. The brand-new LP that teams them with Charlie Louvin includes vintage acoustic numbers like “Sweeter Than The Flowers,” but it also includes versions of “Don’t Let Me Cross Over,” a honky-tonk classic popularized by Carl and Pearl Butler; “Showboat Gambler,” from the England Dan & John Ford Coley rock act; “Too Bad She Don’t Love Me” from Eddie Rabbitt’s publishing company; “Tennessee,” a tune from perennial Cricket Sonny Curtis; and Larry Gatlin’s “Until She Said Goodbye.” The successful single release was “Northwind,” another contemporary Nashville composition. Most important of all, perhaps, are the songs revived from the Louvin Brothers’ repertoire, “When I Stop Dreaming” and “You’re Running Wild,” for they represent the on-going relationship between Jim and Jesse and the Louvin heritage.

“Some of the most requested tunes that we do at festivals are the Louvins’,” says Jim. “We did that tribute album, you know.” Says Charlie Louvin appreciatively, “With Jim and Jesse’s help, I want to do a lot more for the Louvin reputation than just the songs.”

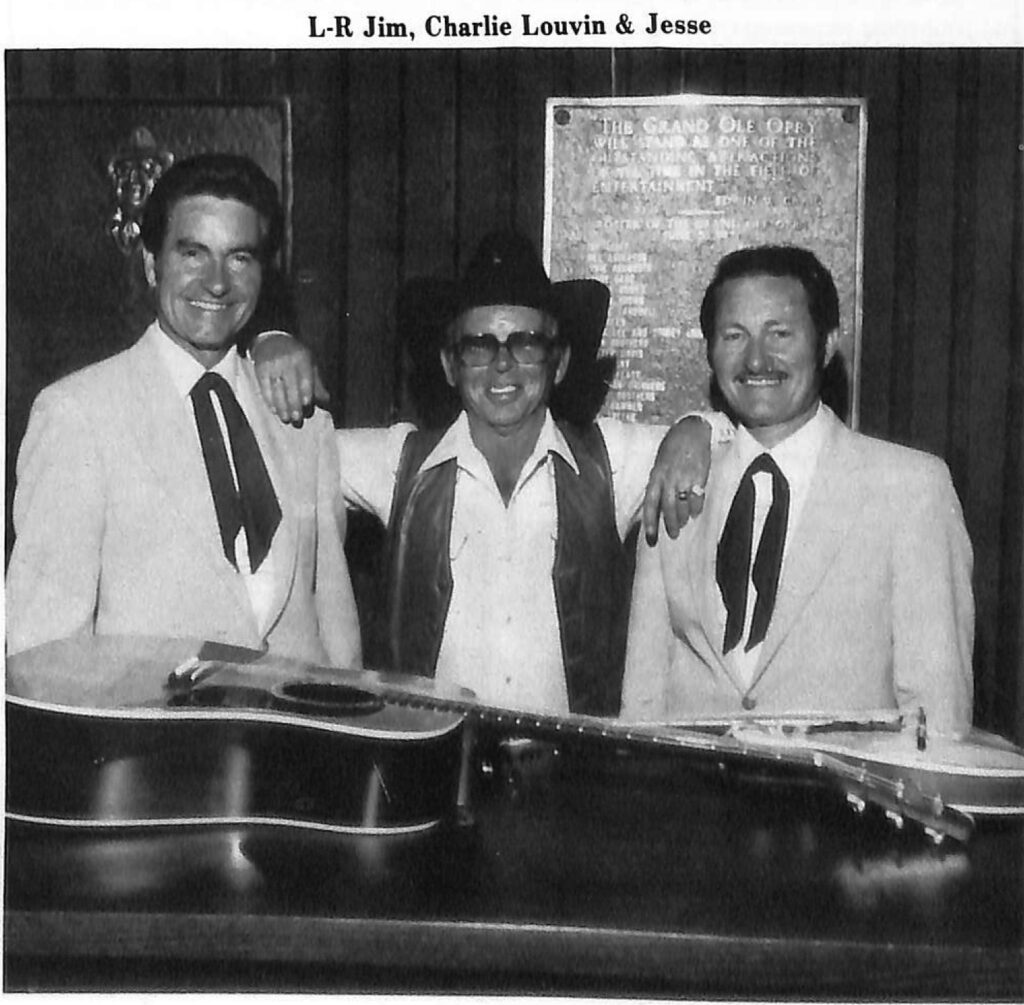

“Jim and Jesse and Charlie Louvin” was Jesse’s idea. He had played mandolin on Bill Monroe’s last album and was thinking of doing another all-mandolin album for a British label when this project occurred to him. The three got together backstage at The Grand Ole Opry and have continued to perform there together lately. Says Jesse, “This fall we’re going to be doing some package shows together. Charlie will carry his band, his people, and we’ll carry ours. We’ll perform separately and then do some things together.”

The music is fine. It’s the kind of music that only vintage, backwoods-reared, country musicians can make together. It is real and authentic and beautiful. Asked whether he’d consider it bluegrass or not, Charlie Louvin answered, “I’d just call it damn good; and I’m proud to put my name on it.” “It could be called bluegrass or country,” offers Jesse McReynolds. By this time in Jim and Jesse’s career it ought to be a moot point whether or not they stick to traditional bluegrass. Nevertheless, Louvin is anxious to point out his position on the matter. “Bill Monroe always said he liked the Louvin Brothers,” he begins. “But one day he was talking about how he didn’t like electric guitars. I told him, ‘Well, Bill, then you never liked the Louvin Brothers, because we always had an electric guitar.’ ”

Charlie’s an outspoken, outgoing man with plenty of guts and gumption. He is quick to speak his mind and quick to charm as well. To call him a delightful, colorful character would not nearly do him justice. Jim and Jesse, on the other hand, are quiet, unassuming professionals who just go on about the business of making a living any way they can. Recalling their many years of stretching bluegrass boundaries, Jim says, “When we first moved to Nashville, bluegrass wasn’t doing that well. We had to get something going on the record charts before we could get any work. And the only way we could get on the record charts was to get booked country. So that’s where we went.” He continues, “In Europe, bluegrass and country are not so segregated as here… In Germany, England, and France we were on a tour with Johnny Cash and Tammy Wynette and Marty Robbins. When we played Paris we went on right in the middle of all of the acts, and we got more encores than anybody else on the show, including Cash … In fact, Cash was waitin’ to go on while we were taking our encores.” Although the new album on Soundwaves sounds more like Jim and Jesse than it does Charlie Louvin, it’s Charlie who has the last word on the whole phenomenon of the McReynolds brothers crossing the lines between the bluegrass and country. “I’ll bet you my farm against your spare tire that Jim and Jesse could walk out on a Kenny Rogers show or an Alabama show or an Oak Ridge Boys show and set the audience on fire,” he begins. “Somebody’s missin’ the boat by not mixing Jim and Jesse with some of the superstars of today! It’s like if everybody was drinkin’ expensive beer and somebody came along with a jug of home-brew. Well, everybody would throw beer away and go with the homebrew. To me, Jim and Jesse is homebrew.” Amen, Charlie.