Home > Articles > The Archives > Joe Mullins—It’s Going To Swell Your Heart

Joe Mullins—It’s Going To Swell Your Heart

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

July 1995, Volume 30, Number 1

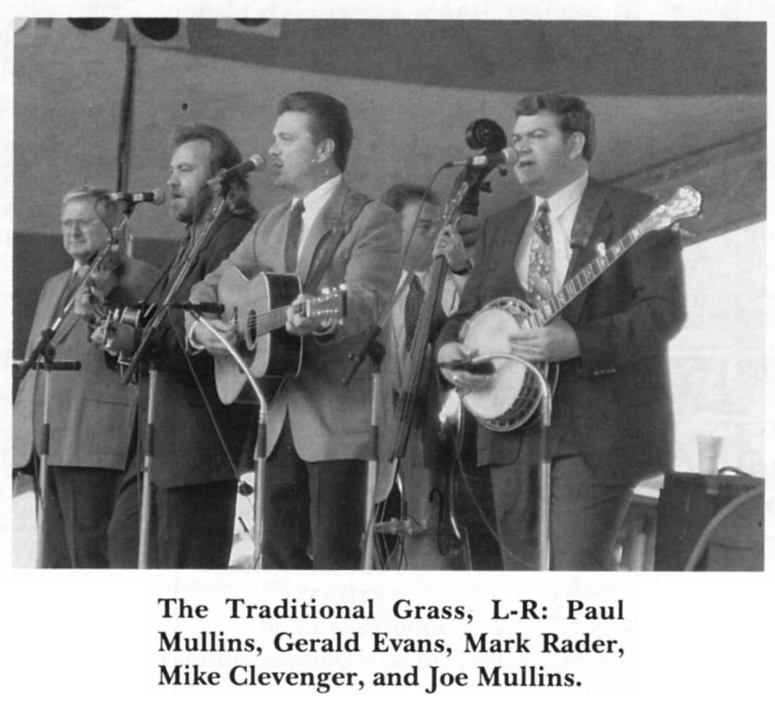

Joe Mullins is passionate about bluegrass music. And he loves to share that passion with others, much, one gathers, as his musician father, Paul, originally did with him, 25 years ago. These days the two of them are kindling the flames of bluegrass fervor in an ever increasing legion of fans, as members of one of the hottest groups of the decade, the Traditional Grass. Though thoroughly a group endeavour, it is clear that those extra ingredients which have helped to propel the band to its current level of success are the relentless dedication, astute resourcefulness, boundless energy, and unquenchable enthusiasm of Joe Mullins.

Joe was born in Middletown, Ohio in 1965, a year after Paul “Moon” Mullins began what was to be a tremendously successful 25 year radio broadcasting career at Middletown’s WPFB. Before getting into radio work Paul had played fiddle with the Stanley Brothers, and he later continued to perform and/or record with many artists such as Ralph Stanley, Jimmy Martin, Moore and Napier, Reno and Smiley, and the Osborne Brothers whenever they passed through the Cincinnati/Dayton area. And they passed through often, thanks to Mullins. He used the immediate success of his radio program on WPFB to build an audience for live bluegrass in the area, and began booking the big name bands into local clubs regularly. Not only did Paul provide work for the artists, he opened his home to them as well, and soon the Mullins household became a haven for road-weary musicians to relax for a few hours between show dates.

“One of the first things I remember,” Joe reflects, “was the first time I saw Bobby Osborne. I couldn’t have been any more than three or four years old. It was one of my earliest memories of meeting somebody that I was in awe of. I was in my pajamas, I got out of bed one morning and staggered into the living room, I guess to turn the cartoons on, and there was Dad and Bobby Osborne sitting there talking. I think they had been working somewhere around town and had come in at the crack of dawn and hadn’t gone to bed yet. I recognized (Bobby) as being one of the Osborne Brothers, even at that early age, but Dad told me who he was. Bobby got me up in his lap and talked to me for a minute and gave me a piece of Beeman’s chewing gum, and I’ll never forget it as long as I live! ‘Yesterday And Today,’ the album that had ‘Rocky Top’ on it—I spent the next year glaring at that thing every day, remembering that piece of chewing gum and remembering getting to see him.

“I remember there was a knock on the door one morning and Jimmy Martin was passing through. Ralph Stanley and his whole band were in and out a lot. I’ve got a picture of me in Bill Monroe’s lap [when] I was like four years old. He spent the day at the house once. Mac Wiseman came and stayed a weekend one time. I remember seeing Red Smiley once before he passed away. Reno and Smiley came into town and Dad went and picked them up off the bus and they came to the house and spent the day. Mom and Dad had a pair of green recliners in the living room. Red stretched out on one of those big recliners. I remember how tall he was. His feet hung over the end about a foot and a half. He was tired and he rested.

“I guess the first [group] I saw on stage was Dad and Jim McCall and Earl Taylor and Benny Birchfield. They worked together out of the Ken-Mill Club. It was a famous club in Cincinnati. Dad was a part of the house band. When I was little I remember him going down there and working nights—sometimes Thursday, Friday, Saturday. There was a bar in Middletown called the Horseshoe and Dad had some kind of a band working out of there most winter weeks, and several times a month, he booked in some of the pioneer artists that he was playing on the radio. Also one of the first times I saw a show on stage was the Osborne Brothers at the Green County Fairgrounds. Dale Sledd might have been working with them and Ronnie Reno, so we’re talking maybe ’71 or ’72.” With this constant exposure to the world of bluegrass, it’s little wonder, then, that young Joe grew up infatuated with the music and eager to become a participant. “I can’t remember not being totally consumed with this kind of music,” he asserts. “It’s just all I’ve ever wanted to do. I can’t say it’s all I’ve ever done. Like most musicians you’ve had to do a few other things to make ends meet, but I’ve never been without music a day that I haven’t listened to it or sang a song, or been involved with it in some way.”

From the beginning Paul Mullins encouraged his son’s budding interest in music. “I guess one of the first things I remember was the Christmas that I was three years old,” Joe recalls. “I got a record player and a guitar for Christmas—like a half-sized Harmony guitar. Even then, I remember sitting with Dad and his friends and they’d be flipping through albums and I could tell what album had the Stanley Brothers on the cover, or the Osborne Brothers or Reno and Smiley. Dad being the great fiddle player that he was, I first learned how to play rhythm with the guitar and how to follow him on some fiddle tunes, and gradually I was just consumed with hearing all the music I could hear. Him being in the radio business, we had several copies of all the great bluegrass albums. In that respect I’m probably one of the most fortunate third generation professional [bluegrass] musicians in the world, because I had access to every bit of the good vintage recordings from the time I can remember. Then, I guess when I was maybe seven or eight years old, I got a cassette tape recorder for Christmas. Then it was hours spent either playing my guitar and trying to sing or playing disc jockey, playing records and acting like I was on the radio.”

Though the elder Mullins must have been a patient and attentive teacher, he clearly was a perfectionist who was careful to instill his own high standards in his son. “One of my true loves,” Joe states, “is to play rhythm guitar, and play it the way it’s supposed to be. Dad’s got a real good rhythm lick on the guitar. When I was growing up and he wanted to teach me timing and how to play with a fiddle or with a banjo, he would show me how he played the guitar, and I would work on that. But he also always told me, ‘Pay attention to Jimmy Martin and Sid Campbell.’ Jimmy Martin is one of my biggest influences, on playing the downbeat, and playing it heavy. Sid was one of the finest rhythm guitar players. And I enjoy from time to time being able to get in a jam session with friends of mine and play the rhythm guitar, and try to make it sound like it’s supposed to. And I guess one reason I enjoy it is because I like to be able to set an example for the way the rhythm is supposed to hold the music together.

“I see a lot of youngsters that put the cart before the horse. They try to play all of Tony Rice or Dan Crary or whoever’s hot licks before they can play good timing, before they can really pound out the rhythm and make a band sound good and full. That should be the first thing a guitar player’s going to learn, especially if he’s going to work on stage—to be able to hold things together with the rhythm. That’s more important than anything you’ll do if you’re going to be in a band, is play right on top of the beat. If you can come into a bluegrass number with the timing and the attitude of guitar playing that Jimmy Martin did, you’ve got no problem.”

When Joe was about 13 he got interested in a banjo that his dad had bought several years earlier. Paul got him started with the basics, and then Joe began to carefully study the music in their vast collection of recordings. “I spent hours and hours with Flatt and Scruggs albums,” he remembers. “At that point, Scruggs was my biggest influence. I can’t say that Scruggs was my very first influence, because of Dad being so close friends with Ralph and having worked with Ralph and Carter. And at the time I was growing up, Dad and the Osbornes spent a lot of time together. I’d say I was first influenced more by Ralph Stanley and Sonny Osborne—influenced as far as recognizing banjo music. But when I got serious about the banjo, I was told by everybody around me that you better pay more attention to Earl Scruggs than anything, starting out.”

His dad’s friendships with many of the great banjo players provided Joe with the unique opportunity to study their playing up close, and he made the most of it. “After I got to where I was progressing through the Scruggs style of banjo playing, that’s when J. D. Crowe was really hot. This was right about the time Keith (Whitley) went to work for him, ’77, ’78—somewhere in there. They were working a whole lot in the Cincinnati/Dayton area, and I got to spend a lot of time with him. I’d known Keith since I was little. He’d been to the house with Ralph (Stanley) and was real nice to me. Dad and J.D. had been friends and had played together back in the ’60s, when J.D. had the Kentucky Mountain Boys.

“In 1979-80 I met Don Reno for the first time since I’d been a little kid. I just couldn’t believe what the man accomplished on the banjo, and how big a contrast it was to what Scruggs and Osborne played. It was on the other end of the world, for a guy learning. But once I got to spend some time with Don Reno, he was a huge influence all at once, and I dug out the Reno and Smiley stuff and I better educated myself on Don Reno’s playing. He showed me how to play a few of the things the way he [did]. You heard Don take a break on anything you want and sell it, no problem. That fascinates the heck out of me. I can’t do it.

“Don Reno played a lot of things with just his thumb. I can do it some, and make it sound tasteful in my playing. He also had a unique roll, where he played forward a little bit and backward on the end of it, and used his index finger playing on the bass string, on the fourth string. I can’t find anyplace where Earl Scruggs does that. Ralph did it. And it’s the only way you can play the same tone Ralph Stanley played on some of that stuff. I do that some, if it fits. Ralph’s banjo playing on the Mercury recordings from the 1950s is his most influential period for what I play. He played real good straight melody, he played real good timing. Ralph is one of the best musicians and best banjo players at being able to play while he sings. Few people that sing the part like Ralph did could play at the same time. I can’t do it yet, but Ralph could play a chop on the banjo, he could play his timing on the banjo while he was singing, superbly. And I work on that.

“Everybody was stressing the timing,” he continues. “You’ve got to play the timing, you’ve got to play on top of the beat, you’ve got to play with drive, you’ve got to play with tone, you’ve got to play with separation. Everytime people would rattle off those qualities, they’d say you’ve got to listen to Earl Scruggs. That was the main thing I concentrated on, was getting the basic bluegrass banjo style, built around Earl Scruggs’ music, like every good banjo player has. J.D. Crowe and Sonny Osborne were masters of backup, and still are.

“I grew up with all the admiration in the world for those pioneer artists who made banjo music. As far as influences, I mentioned Scruggs for the basics, and Sonny for backup and really being able to expand and play something unique, Crowe for his great backup and his taste and tone, and Reno for his originality and his ability to play anything in any position. And eventually, by the time our group started playing a whole lot, I was fortunate enough to kind of combine all that.

“I thoroughly enjoy every ounce of music made by Flatt and Scruggs and the Stanley Brothers and Monroe and Reno and Smiley and Jimmy Martin and Jim & Jesse and the Osborne Brothers—the creators of bluegrass music. None of them sound the same. They all had their own thing. And I know that I had to find that. But I have heard several recordings by all of those people every day of my life. Being that influenced, I feel fortunate to be able to play all those styles. If we play a Flatt and Scruggs tune, I can play it just like Earl. If we play a Reno and Smiley tune, I’m going to play it almost like Don, to a T. To me that’s the way it’s supposed to sound. I can play a Stanley Brothers’ tune and I can play what Ralph played. I can do it for Sonny Osborne, I can do it for J.D. Crowe, I can do it for Allen Shelton. I’m not saying this boastfully. I have made myself as knowledgeable as possible with the banjo, on all the great bluegrass recordings.”

Though Joe has studied meticulously the work of the bluegrass pioneers, he stresses that this is just the first step. First one must understand what has been done before by the masters, and then, incorporating that knowledge, move toward creating a style of one’s own. “(When I play a Traditional Grass song),” he explains, “there’s where the difference comes in. That finally all comes back to me when we take a song and make it one of ours. If it’s something we have written, something that’s never been done, it’s a piece of cake for me to play something original on it, because I’ve got all these influences to draw from. And somehow the combination comes out and it sounds like Joe Mullins playing the banjo.”

It’s true—though one can clearly hear the influences of all of Joe’s heroes at different spots in his playing, the final product is a distinctive style that is uniquely Joe Mullins. He has made himself a master of timing, drive, tone, and precision, in the Scruggs tradition. His backup and fill work is tasteful and appropriate, with a decidedly bluesy edge. His playing overall is compellingly powerful, yet because of his flawless timing it somehow feels light and lilting at the same time. Beyond the technical qualities, there is a joyousness that comes through, a sense that this music is a celebration, which for Joe it truly is.

Watching Joe Mullins play the banjo on stage, one can almost see the creative wheels turning as he approaches each banjo break with renewed intensity. “I love to play by the seat of my pants!” he declares. “I love to go out on a limb. That’s what excites me about Earl Scruggs and Sonny Osborne and Don Reno. Those three in particular were such masters of their instrument. They dominated it so forcefully. Sonny still does. His knowledge of his instrument allows him to play it all. Sonny knows so much banjo that if he didn’t play what he thought he should be playing right then, I don’t care if it’s back-up or if it’s his break, he would explode. That’s the way I perceive his music. And I have the same feeling. You get out on a limb and sometimes it’ll break off behind you. But when you can get out of it and you come out smelling like a rose, you’ve created. Earl is famous for it.

“I can seldom play a break the same way twice, on something of ours, something that we do on the stage regularly. I’ve got off the stage before and (had) somebody come up and say, ‘How did you play this right here?’ And I’ll start playing the break and I can’t play it just exactly like I did 20 minutes ago! In the live performance setting, you’ve got to be relaxed and natural, and my natural inclination is to play what’s going on right then, not to play what I recorded two years ago in the studio. Right then, what’s going to fit, what can I do a little different this time? And every time you do something different, whether you come out or whether it goes to hell on you, you learn something. And there’s a never ending process right there, of playing innovatively.

“When I say play it innovatively, and play by the seat of your pants, and get out on a limb, there are boundaries. I’ve learned this from—Doyle Lawson is a real good example—of a guy that can convey the same thing on stage as his album does, commercially and artistically, (so that) you want to buy his recording. If you heard a song on the radio by somebody and you go to see them live and you request that song, you expect it to be something like what you’ve heard on the radio. And there’s where I go back to the fact that, regardless, I try to get the melody in there. Sometimes you play around it, but at least at some point in the game people can identify what I’m playing. I’m a firm believer that if I play a banjo break, if you don’t recognize the song, then I’ve not done what I was supposed to do. You’ve got to play the melody!”

Joe’s rule of thumb for deciding whether to use a capo on a particular song is always to find the melody first. “I use a capo most of the time if it’s in an A or a B flat or a B position. But I was sick and tired of seeing everybody play the same pattern, everybody have to slap a capo on and play out of some easy position. I like to play without a capo, as most people do, in E and F. I seldom capo to play in either one of those positions, but it depends on the melody. I hate to capo out of C. I mean, that’s at the fifth position. It’s just something I don’t enjoy doing. I think you’ve got more options and you’ve got five more frets to play off of when you don’t have it on there. There’s only one arrangement of ours ever that I use a capo in C, and that’s ‘Back To Hancock County.’ I can’t find the melody otherwise, and play that song with the kind of force that it needs.”

In 1993 Joe was approached by Rich and Taylor Banjos to be an endorser of their new line of instruments, and he couldn’t be more pleased with the affiliation. “It has been a real help in my career to have one of their banjos. It seems like I have had more of a desire to play since I got the instrument that I play right now. The banjo that I’ve got was the Carolina model, the maple, gold-plated. I picked it out in June of ’93. We were working the Lexington, Ky., festival on Friday, the 11th, and Darrel Adkins came and he had two or three Rich and Taylor banjos. He said, ‘Play these, and figure out which kind you want, and then we’ll get you one.’ I said, I like this one, here.’ He said, ‘Well, we’ll get you one of those.’ I said, ‘No, I want this one. This one sounds exactly like what I’ve been looking for.’ It was a scary thing, because the banjo was two days old, two days. And it sounded like I wanted a banjo to sound, after two days. I said, ‘You’ve got to give me this one, because if it’s two days old, that’s the day my little girl Sarah was born.’ She was born on June the ninth, 1993, and that banjo was completed in assembly at Rich and Taylor the same day. And that made it unique enough that (he said), ‘OK, we got to do it then.’ And he gave it to me. I didn’t take it home right then, he had to take it and display it at bluegrass festivals in Bean Blossom and Summersville, W. Va., and then he brought it back to me. I got it on July first and went into the studio July second and recorded four or five of the songs on our (“10th Anniversary”) album with it. We hit the road that weekend, after we finished in the studio. We worked four or five different places and we came across a dozen musicians that had been at Summersville and Bean Blossom. Besides (having it) on display, Darrel had Ron Block and Rob McCoury, and a dozen other people used it on the stage. They were saying, ‘You got the best one!’ They said, ‘We like all of them, but boy, we wanted yours and he had it promised to you already.’ I’m just absolutely thrilled with my instrument.”

Though he had loved to sing since he first took an interest in music, it was not until Joe got to know singer/guitarist Mark Rader in 1983 that he began to work seriously on perfecting the strong, clear tenor harmony that is now one of the trademarks of the Traditional Grass sound. “Mark and I spent a lot of time together, just he and I, practicing banjo and guitar and singing,” Joe relates. “Mark had played in a band before we started (the Traditional Grass). Mark had been on stage. I was only 17 when we started fiddling around. I didn’t have very much talent in the way of singing right then. I knew the part, but I didn’t have very good control over my singing, I didn’t blend very well. So we woodshedded a whole lot singing duets, and it finally started getting good enough to where I was more comfortable with my singing.”

In his singing, as in his banjo playing, Joe drew inspiration from his musical heroes. “The Reno and Smiley duet was a great influence on me and on Mark and I singing together. Just as the Stanley Brothers were. Just as the Louvin Brothers were. I can’t leave out Curly Seckler. I mean, gee whiz, the Flatt and Seckler duet was so perfect. I can’t say I’ve ever tried to sing just like anybody else, but if we sing a Flatt and Scruggs tune I can’t help but sing a little bit of the same phrasing and emotion as Curly Seckler. And the same thing if we sing a Stanley Brothers tune, you’d better try to sing it just a little bit like Ralph or to me it isn’t going to sound right. Ralph Stanley and Bobby Osborne, that’s two of my favorite vocalists. I can hear Ralph talk sometimes and break down and cry! He’s got the mountain sound, and he’s got so much feeling and so much emotion. Bobby Osborne is the same way. Bobby Osborne’s one of the greatest all-time vocalists ever, anywhere, period.”

For the first six months of its existence, Joe says, the Traditional Grass honed its skills playing mostly bluegrass classics. “I think that’s the groundwork for playing authentic bluegrass music, to learn first generation songs and learn them right.” But they knew the importance of finding fresh material and creating an original sound, and soon they were drawing from more diverse sources. “Even at that time, when we were just a local band, just hobbying around at this, we were very selective in material,” Joe stresses. “We were fortunate to have some Flatt and Scruggs material from live shows, that they hadn’t recorded, that we dug through. With the big record collection that Dad had, and with the different tastes between me and Dad and Mark, we started pulling some things out that hadn’t been done in our music. We dug through a lot of obscure stuff for material.

“When we started trying to expand our repertoire, to not do so much standard bluegrass, I guess that might have been when I started trying to write songs. The first two or three times I tried it, I was so influenced by all the music, everything I wrote sounded like ‘If I Should Wander Back Tonight’—it did to me. I guess the first thing I ever wrote that we ever did anything with was ‘My Memories Aren’t So Precious Anymore’ (from the ‘Howdy Neighbor, Howdy’ CD).”

Joe recalls how he wrote the song: “(At that time) I worked in a shop that made countertops. It was a terrible job for a banjo player, running routers and table saws all day. It was scary. That’s the reason I finally quit. I was worried about cutting a finger off. But I was working there one day, and I might have been humming ‘Precious Memories,’ I don’t know. But I just got the idea—‘Precious Memories’—‘My Memories Aren’t So Precious Anymore,’ and in a couple of hours I had a verse and a chorus, and wrote it down on the back of a lumber order. I stuck it in an old jacket I was wearing to work back and forth and it stayed in there for about six months before I sang it to anybody.

“I guess people have different concepts of how they can write a song. I just get lucky. That’s the way I put it. On our ‘10th Anniversary’ (Rebel 1718) album, I wrote ‘The Country Girl Blues.’ That’s the easiest song I have written so far, and probably my favorite of the stuff I’ve contributed to the band. We’ve gotten quite a good response for it from the stage. Mark does a great job singing it. It really fit what we were doing on that album. I wrote that whole thing in five minutes. I just had the idea and started humming the melody, and just got lucky.” Joe also contributed a gospel song, “Rest For His Workers,” which he wrote with his friend Gary Carpenter, for the “10th Anniversary Collection” CD.

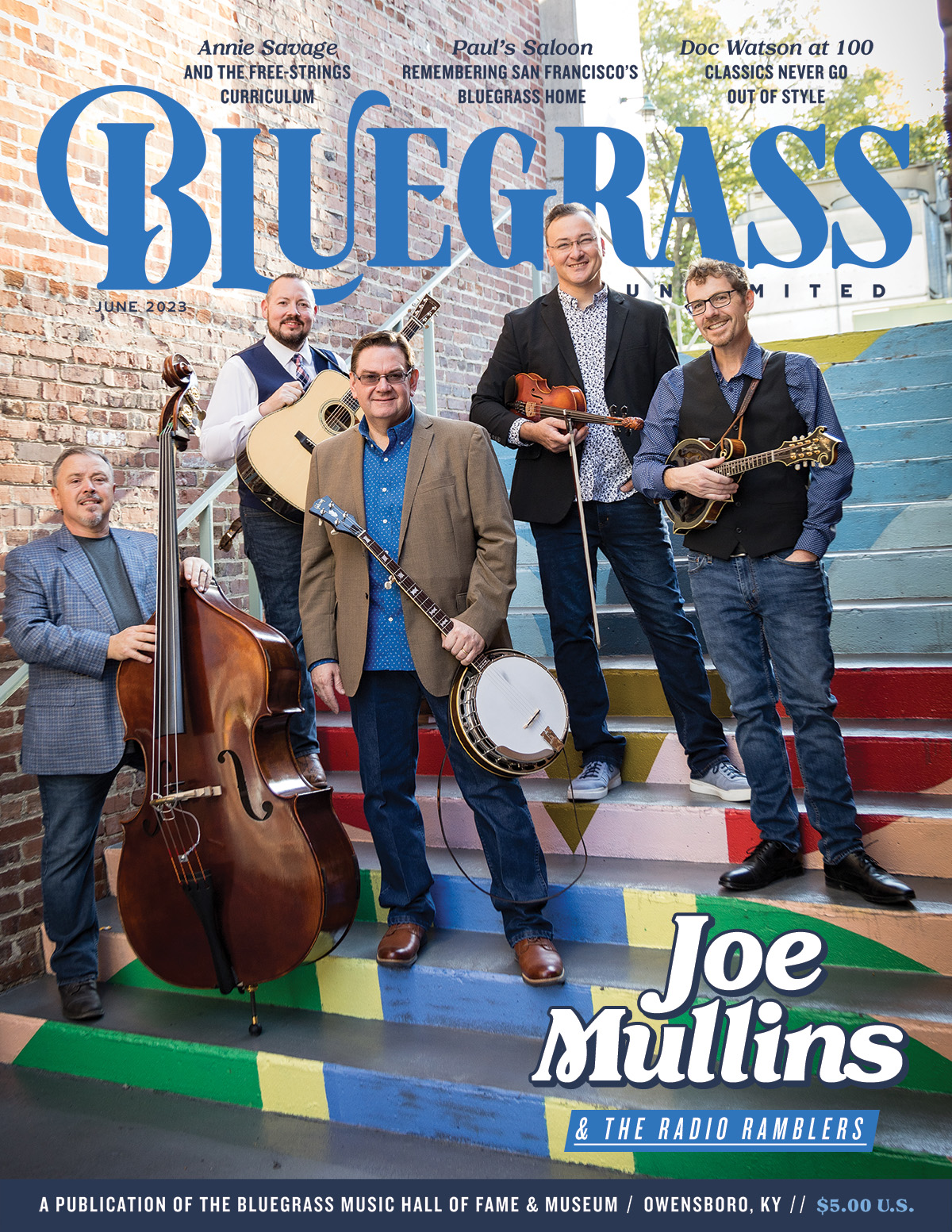

For the band’s latest release, “Songs Of Love & Life” (Rebel 1721), Joe teamed with Traditional Grass mandolin/fiddle player Gerald Evans to write “Together ln Our Hearts.” In all, Joe, Gerald, and Mark Rader contributed six original songs to the new project. The band members feel that this is their best recording to date, and Joe is especially excited about the new material that Mark has written. “Mark’s songwriting just blows us all away, as it does a lot of other people in the industry. As we speak, we’ve got, off the ‘10th Anniversary’ CD, two songs in the Top 30 and he wrote both of them. That’s quite an accomplishment, I think, for only your third major release. Some of the songs Mark has written for this new album, I really expect them to be well received. I expect them to become trademark songs for our band.”

“Songs Of Love & Life” is the fourth recording by Traditional Grass for Rebel Records. They signed with Rebel in 1991, and immediately began a mutually productive relationship. At that time the band made a commitment to full-time national touring, and with Rebel’s support they have risen from the regional ranks to headliner status in just a few years. Their dedication and hard work has made the Traditional Grass one of Rebel’s best selling acts as well.

“It’s a wonderful relationship,” Joe proclaims. “I really appreciate the fact that Rebel, for over a quarter of a century, has been primarily a bluegrass label. And that’s one reason I looked to them to help us with our career. We had an appointment with [Dave] Freeman, in the summer of’91. He asked for original material, which goes without saying, that’s part of what it takes, standing on your own two feet, with your own song to sing. We told him we had some original material to add into an album project, and he welcomed us and we set it up to do some recording for Rebel. Next thing you know, we recorded ‘The Blues Are Still The Blues’ and ‘My Memories Aren’t So Precious Anymore’ and ‘Lord Lead Me On Home.’ Mark wrote one, I wrote one, and Gerald wrote one. And they’re three of the most popular things off that album, and that really put the incentive into us to continue (to write). We all wrote something for the gospel album, and (on the ‘10th Anniversary’) album, I think we wrote seven out of the sixteen songs on there. The opportunity given us by Rebel was very inspirational in that. So it’s worked out real well.”

In addition to their work with the Traditional Grass, Joe and Gerald Evans recently completed an album of banjo and fiddle tunes for Rebel. “We’ve really got a passion for fiddle and banjo (tunes),” Joe attests. “I think that’s the core of our music. It’s a real traditional art form, to play without anything but a banjo and a fiddle, in the form that Earl Scruggs and Paul Warren were so famous for. Dad’s influence on Gerald’s fiddle playing really makes it easy for us to play well together. The tunes that Dad’s played for years, Gerald really has learned to play them well, and is excited about getting to play them. They’re things I’ve known all my life, most of them. We’re calling the album ‘Just The Five-String And The Fiddle,’ because that’s the way (Lester) Flatt said it.”

About two years prior to the band’s signing with Rebel, Joe began to take over booking and management for the Traditional Grass. Initially, when the band was working on a part-time basis, it was easy for Paul to take care of bookings through his many contacts in the industry. But as the band got busier and business affairs began to consume more time, Joe became increasingly involved. “When we started getting poised to go on the road full-time, that’s about the time I took over the booking,” he explains. “I started sharing it with Dad and educating myself on it, and eventually it got to where I do just about all the booking and promotion. I developed a knack for it and the ability to get us places we hadn’t been. By the time we got to work with Rebel Records, I got to where it’s a passion. I was overcome with the fact that I wanted to do this for a living. But if you’ve got a passion to be on stage performing three or four days a week, that means you’ve got to book three or four shows a week. If a week or 10 days go by and I don’t book a show, I can’t sleep good! Because it’s job security for one thing, plus it’s part of accomplishing your goal of performing music for a living.”

If Joe wasn’t making his living performing bluegrass music, you can bet he’d be doing the next best thing—programming it on the radio. As a teenager Joe graduated from listening to his dad on the air to having his own radio shift each day after school. By the time he was in his early 20s, he had teamed with Paul to format all of the music for WPFB. “In ’87, ’88, and the first part of ’89, things were really wonderful with the radio station,” Joe recalls. “I was the Music Director and the afternoon personality on the air, and Dad was the morning personality, and we formatted a real good mixture of current country music that was still country. We didn’t go out on a limb and play some of the pop things, we played what was good that was current. We played older country music hits, and we played album cuts from Haggard and Jones and Ernest Tubb and Hank Snow, mixed in with bluegrass music that had a real good commercial appeal. Dad had made a good living in the radio business for years, and I was well on my way. But times change. The management had some problems up there that we couldn’t see through. The last day that we were on the radio in Middletown was March eighth of 1989.”

Joe took a year off from broadcasting, but by March of 1990, he was back on the air at WCNW in Fairfield, with a daily lunchtime show, which he continues to host today. “It’s a gospel station,” he notes. “They play Christian programming and Southern Gospel music a majority of the time. But noon to one, Monday through Friday, I do the Hymns From The Hills program, which is ninety percent bluegrass gospel. If I play something that’s not bluegrass, it’s a hymn by Loretta Lynn or George Jones or Connie Smith or somebody that fits the format. I grew up hearing Dad on the radio and learning the unique style of ad lib radio commercials and the personal contact between the advertisers and the audience. I’m fortunate enough that I developed enough personality and enough of a knack for selling a product on the air, that it’s been quite successful. I sell every minute of [the advertising], I’m in charge of the hour. It’s sponsored by such (companies) as True Value Hardware and Goodyear Tires, and even Sears & Roebuck at one time sponsored the program I have now. It’s quite a success in the Cincinnati radio market. I’ve got a very loyal audience. They support the sponsors. A great portion of the audience was developed throughout the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s when Dad’s radio career was there and when I got in on the tail end of it. But there’s new people that listen, there’s young people that listen, there’s factories and office buildings throughout Cincinnati that listen. So that’s something that I’m real proud of, is being able to keep this radio format on the air professionally.”

In the late ’80s, Joe picked up where his father had left off in yet another area: concert promotion. As a musician and a fan, he had seen enough poorly promoted events that he developed an interest in trying his hand at “doing it right.” “As an industry professional I’ve had to go into some terrible venues,” he attests. “You go work a date that you’re excited about and you get there and the guy hasn’t advertised it and there’s nobody to watch you, nobody knew about it. You get there and the setting is very improper to present this music. When we get a chance to promote a show, I like to change that. While we were still with WPFB I started a little concert series at the American Legion in Franklin, Ohio, where I live. I’m proud of the way we promote a show. Dad had been doing this for years, but I kind of bit this one off, and it tickled me to death that it worked.

“Well, I got the itch to try to continue the thing. And so we spent three or four winters, with the little American Legion only holding a couple hundred people, doing something about once a month. We always did those (shows) with the Traditional Grass and another headline act, a double bill. We spent two winters being sold out, people having to come two and three hours ahead of time to get a seat because it was small.”

When the series outgrew the American Legion building, Joe was able to find another, larger venue in the area. He moved the series to Conover Hall in the winter of 1991, and it continues to thrive there. “Conover Hall is a nice facility,” he confirms. “It’s easy to find. It’s just off 1-75, Franklin, Ohio, exit 38, which is just about 15 minutes south of Dayton, about 30 miles north of Cincinnati. There’s a huge audience for our music right there where we’re at. We’ve got our mailing list established and a local radio program supporting us to get a crowd in. It happens once a month, December through April, five programs, three acts (on each program). It lets us be home a weekend, and it let’s us (make) our audience available for Del McCoury, the Country Gentlemen, Ralph Stanley, the Osborne Brothers, Third Tyme Out, the five headline acts that came in this year. We send a flyer to everybody (on our mailing list) in Ohio, Kentucky, and Indiana. Plus we work the road week after week, and we plug it. And all the other acts help because they like to work in our neighborhood.”

If you’re starting to wonder how Joe Mullins finds time and energy for his many endeavors, hold on—that’s not all! In 1992 Joe was asked to be secretary of the International Bluegrass Music Association. Through IBMA he has found new opportunities for sharing his passion about bluegrass with others, and for contributing to the future success of the music.

Prior to signing with Rebel Records and committing to music full-time, the Traditional Grass had had little contact with IBMA, though they did perform at FanFest once in the late ’80s. They returned to Owensboro in September of 1991, and set up a booth at the IBMA Trade Show. “I learned a little bit more about the Association that week,” Joe recalls. “And as the year went by I got familiar with the showcase process and we put in for a showcase. So we showed up in ’92 with a booth, and we got chosen to showcase at a luncheon. I learned even more about it then, because we had the Rebel contract finally, the ‘Howdy Neighbor, Howdy’ album had been out a few months, and we were looking at, we’re going to work the road full-time, this is our career now. And so my goal was to educate myself completely on how IBMA worked, what I could do to help it, what focus I needed to put into being a part of the Association.

“And I had some misconceptions, just like a lot of people do, about how it was governed and about what the objectives were for the Association and what direction they wanted to take the music. The more time passed, the more I learned about it. And as far as understanding how to be a viable part of the International Bluegrass Music Association, all it takes is education about how the Association works. There’s a real lack of knowledge on the nonmembership’s part, about what our Association does, and one thing that’s holding us back a little bit right now is (that) even some of our membership isn’t educated enough about the way the Association works to talk to each other about it or to talk to non-members. It takes a little time, and maybe it can be a little confusing or complicated, but once you learn what this Association is all about and how it does work, it’s going to swell your heart. It’s going to overwhelm you that this many people worldwide care enough about this music to want to see it thrive continuously. That’s what IBMA’s all about.

“When I get into Owensboro (for the annual Trade Show) on Monday night, I am immediately elevated emotionally, to see people from all over the world that love this kind of music. To see them all at one spot, enjoying the music and each other’s company, and see the industry professionals work together to make certain that this kind of music is an influence on society. I think it’s absolutely fabulous. When Pete Wernick did the Awards Show presentation with the kids (in 1993), (we) had five youngsters out there in front of the world, playing, and playing well, saying, ‘Look, world, we’ve got 15 year old kids that love our music enough to learn to play it professionally, and these 15 year old kids are going to be around for the next 60 years, seeing this thing happen!’ We had the world watching those kids, or hearing them on the radio, seeing them on the video that was made. And, man, I sat there and was overwhelmed with emotion, knowing that we’ve finally got an Association that can get that accomplished.

“(The 1994 Awards Show) was one of the greatest nights of my life in this business, because the Osborne Brothers went into the Hall of Honor, for one. And number two, the production of the awards show had a real good international flavor to it. I had the good fortune to be sitting right behind Bobby and Sonny.

When the Japanese girl kicked off ‘Blue Moon Of Kentucky,’ she played one little fill at the end of her break that was perfect. And Bobby and Sonny were beside themselves. And I was, too. They were just flabbergasted. Bobby Osborne beat his knees and laughed and was in awe. That’s a great thing. That’s absolutely fabulous, to see a child from the other side of the world, from a completely opposite culture, have the opportunity to get in front of the world and play ‘Blue Moon Of Kentucky’ on the fiddle. Man, that’s great! That just tears me up. And then to see two people like Bobby and Sonny Osborne, that have devoted their life to this kind of music—to see them be able to sit down and see people from all over the globe come out and show their respect and awareness of the Osborne Brothers’ music and show that everybody knows Rocky Top.’ If everybody didn’t know ‘Rocky Top,’ we might not be where we’re at today, and I thank and respect Bob and Sonny for it every day. And it was good to see the rest of the world do it. That’s what IBMA’s all about.”

“I was asked to be Secretary [in] ’92,” he continues. “It was before we did our showcase (for IBMA). That all happened that week. As passionate as I am about seeing the music survive, prevail, and take a step forward daily, I thought I’d better take the job, I’d better be a part of this. And I don’t regret it for one minute. I’m absolutely delighted to be with other professionals in a capacity where we can help each other advance the music. That’s what we do. The duties of the Secretary, as far as hands on things, aren’t a whole lot. I work on a few committees. I kind of am on my own mission as far as how I like to participate and help the organization. The officers are not voting members of the Board. We are set up to govern the Board and assist the Board in relaying things to the membership—to be like a strengthening unit between the members and the Board.

“If you are a bluegrass professional and you don’t belong to the Association, I’d like the opportunity to ask you why. If you’ve got a question about the Association, I’d like to be able to answer it for you. Don’t be afraid to ask it. If you’ve got a misconception, if you’ve heard something that has turned you off about our Association, you’ve probably heard it from somebody that’s not educated about the way it works. We all need to belong to this Association, to make things happen. Learn what we do and how we do it, and then if you tell me that it’s not needed, then you aren’t a professional. That’s pretty strong. But I’ll say this: if someone reading this article is one of these people that stand back and continually find fault with the Association, I think it’s out of a lack of education and professionalism. I think if they want to be a professional part of the industry, it is a responsibility to learn about it. Not only to learn about the industry, but to learn about their trade association and be a part of it.

“If you see a problem with the Association or if you see the Association take a step in a direction you don’t agree with particularly, the best way to change that is to join. I, as a wholehearted supporter of this Association, see a few things that are lopsided, and the explanation as to why it is this way is that everybody doesn’t belong. If everybody belonged, everybody would be represented, everybody would be satisfied with the direction things went in, because it would be a majority vote. Right now every professional in this business is not a member of the International Bluegrass Music Association, so you only wind up with it being governed in the direction of the ones that are. So there’s the solution to your problem. If you don’t like what IBMA does for whatever reason, it’s because you don’t belong.”

One of the most important things that IBMA is currently doing, Joe stresses, is obtaining market research which will be instrumental is proving the viability of bluegrass music to corporate America. “One thing that we will accomplish over the next year or two is getting usable, valuable research in our hands that defines the bluegrass audience a little better, as far as their buying habits, as far as their place in the business market. (Then) we can have a better chance of getting corporate sponsorship. When we get this in our hands, if we take it to Crysler or Levi Strauss or Pepsi, just like every other business does when they seek corporate sponsorship, I think we’ll have something they’ll pay attention to. I want to see the day, quite soon, when you can see the Traditional Grass, the Del McCoury Band, the Lost And Found on a Marlboro tour, for example. Everybody knows about that. You can work six or eight major cities in a two week time, and everybody knows about it because the dollars are there to support the music.

“You’ve seen Tom T. Hall selling Tyson chicken. You’ve seen Barbara Mandrell selling clothes and Reba McIntyre, Clint Black doing television commercials. I want to see the day when the Nashville Bluegrass Band or the Traditional Grass or Alison Krauss or whoever is doing a commercial for Dodge trucks! We’ve got the people out there that it would influence, and it would influence the world to see a music this powerful available to society. I want to see Third Tyme Out—anybody you want to name—doing a Wrigley’s chewing gum commercial and playing ‘Katy Hill’ or something like that, instead of just ‘chewing gum music.’ We got rid of the hay bales (at the 1994 IBMA Awards Show). The industry still struggles with that (image). When you see bluegrass music on television in a setting like that, it’s pathetic, it’s a farce with acoustic instruments. That’s something we can correct. When we get some market research, we can say, ‘Look, this music is a valuable part of commercialism these days, and let’s do it right.’ I want to see that happen. I think market research will give us a chance. That’s one of the things IBMA is working on.” The way things have been going for the Traditional Grass, Joe’s dream of one day appearing in television commercials seems entirely realistic. In 1994 the band appeared on national TV twice, first on the July fourth bluegrass special on ABC’s Nightline and in November in a feature on TNN’s Country News program. Since the fall of 1993 they have been working regularly with a publicist, enabling them to gain exposure in such mainstream publications as The Washington Post, Tower Pulse and New Countiy, which picked the “10th Anniversary” recording as one of the 104 Best Albums of 1994 and gave it a 4 1/2 star (out of 5 possible) review—a higher rating than it gave George Strait, Alan Jackson, Reba McEntire, or Clint Black.

Joe is pleased with the level of name recognition the Traditional Grass has achieved and is proud of what the band has accomplished to date. He has a jam-packed touring schedule booked for 1995 and is looking forward to taking the exciting fusion of traditional and original sounds of the the Traditional Grass to an ever increasing legion of fans. “I enjoy getting to see us play places we haven’t been before,” he attests. “I enjoy getting our music exposed to audiences that are familiar with us also. It gets a little easier all the time. We’ve been very fortunate. We’ve been well received, and I’m very thankful for that. I enjoy being on stage in front of people more than anything. I enjoy our original material, when we can make it sound the way we want it to in the studio and see it received by the bluegrass public.

“And I’m very flattered that people recognize the sound of the Traditional Grass,” he adds. “It tickles me to death when people say, ‘ I hear a lot of groups and I just can’t tell them apart. Boy, as soon as something of yours kicks off on the radio, I know who it is in just a couple of beats.’ That’s very flattering, because that’s the way it has to be for you to create your own music. We finally can record an album and have people recognize off the bat that it’s us. That’s what one of our goals has always been. We don’t sound like anybody else, don’t want to. I want us to sound like the Osborne Brothers in my heart, but I really don’t want us to sound just like them, I want us to sound as good as them.”

In a 1992 review of their “Howdy Neighbor, Howdy” recording, Bluegrass Unlimited touted the Traditional Grass as being “poised to become the premier bluegrass band of the 1990s.” With Joe Mullins at the helm, they are well on their way. And it’s a good bet that one day the Traditional Grass may take its own place beside the Osborne Brothers in the Bluegrass Hall of Honor.

Penny Parsons founded the Penny Parsons Company in 1991, specializing in bluegrass and acoustic music public relations and consulting. She also works as a free lance journalist/photographer, and as a regional sales representative for Record Depot distributors.

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Enjoyed this article so much. Love hearing about all the famous people who stayed at your home. All I could think was your mama was sure busy. By the way; my birthday is June 9. Glad uou got the banjo born on my birthday !