Home > Articles > The Archives > Stringbean

Stringbean

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

January 1974, Volume 8, Number 7

David “Stringbean” Akeman was probably more loved as a total personality than anyone in show business today. He criss-crossed bluegrass and country lines for nearly four decades and, if somebody had tried to define which side of the fence he belonged on. String would have declared, “P’shaw! Both!” Perhaps he simply belonged to the fans who claimed him.

At the time of his death on November 10, Stringbean left behind a rich heritage of songs, many of them learned as a boy in the hills around Annville, Kentucky. All of them were tunes which lent themselves to the five-string banjo, the king of bluegrass instruments.

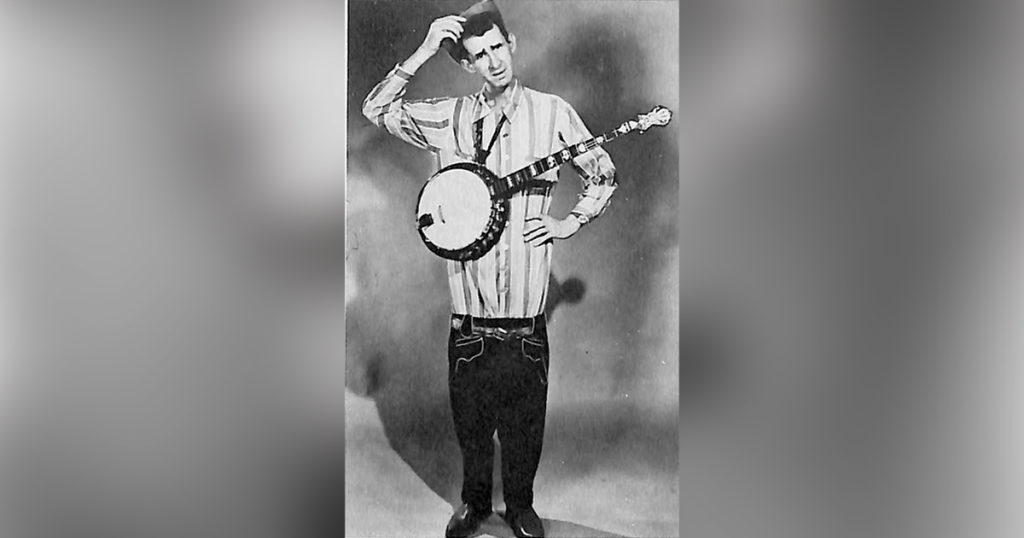

String’s love affair with the banjo began as a child. He listened to his father, James Akeman, pick the banjo late in the evenings when the corn was pulled or the tobacco harvested. String was fascinated by the strings which he claimed danced. He disliked school and endured only six years of it, but he loved the outdoors. When he wasn’t hunting or fishing or tramping through the woods, he was borrowing somebody’s banjo.

But banjo picking was not born in him. “I was twelve ‘fore I could play a tune. Took me a whole year to learn one song. After that, away I’d go. A whole year. One song,” String admitted. His first banjo was a homemade one. “Didn’t have no frets.” String and a friend made the banjo and he bought out the other boy’s interest with two chickens, dressed and ready for the pot.

String squeezed in several years of baseball, too, and considered a career in the pros but scouts seldom visited the hill country of Kentucky. But baseball was the only other career ever to entice String and he found himself strumming a baseball bat, waiting for his turn at home plate.

Such a strong urge to make music sent eighteen-year-old String to Lexington, Kentucky in 1935. “Pa said I’d never make it. Said I won’t good ‘nough,” String remembered a few months before his murder. “But Pa didn’t know I was determined. Determination. That done it.”

It did and String went to work for Cy Rogers and the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers at WLAP in Lexington where announcer Acey Martin forgot his name and called the six-feet, 2 inch lanky picker “Stringbean.” The name stuck and few would have recognized the names of “Mr. and Mrs. David Akeman” in the obituary column. They were “Stringbean” and “Mrs. String” to friends and fans over the United States.

At WLAP String enlarged his repertoire to include “Mountain Dew,” “Pretty Polly,” “Coming ‘Round the Mountain,” and “Maple on the Hill.” Except for songs he wrote himself— “Barnyard Banjo Pickin’ ”, “I’m Going to the Opry and Make Myself A Name,” “Hot Corn, Cold Corn,”— String added only a few numbers to his show. “Folks want the old songs. Songs I sung all my life,” String explained. “Like ‘Cripple Creek.’ That’s a favorite. Everybody’s favorite.”

For awhile String traveled as a black-face comedian until he joined Charlie Monroe’s Kentucky Partners. His next job landed him on the Opry in 1942 as a member of Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys. String stayed on the Opry until his death, having performed for the last time only a few hours before robbers surprised him and Estelle in their little country home.

Only a six-month Army hitch interrupted String’s career after he started on the Opry. After injuring his back in the Infantry, he was discharged and toured awhile with Lew Childre, practicing his comedy routine and discovering that people all over the United States loved his mountain voice.

Stringbean’s jokes, playing and singing, clothes and expressions seldom changed during his thirty-eight years of show business. Neither did his manner of living. At the time of his death, he and his wife of twenty-eight years, Estelle, lived in a three-room red house in the hills outside of Nashville. The rooms were neat and livable. String owned several expensive guns but only a modest color television set. He had a small air conditioning unit and a tiny electric heater just in case the Fireplace didn’t put out enough heat. He chopped his own wood.

In good weather, Stringbean and Estelle headed for a lake, usually Center Hill Lake where he owned a cabin and kept his best boat. His door was always open for friends who joined him fishing. Bill Carlisle, Porter Wagoner and others who fished with String, often talked to themselves on the lake because String would sit for many hours without ever saying a word. When he did speak, it was to say something good.

String also walked in the woods of his hundred and forty-three acre farm. In bad weather, though, he stayed by the fire, telling Estelle what to say in his famous “letters from home.”

Sometimes String entered the recording studio but he was not famous for his record sales. “This one sold under 6 million,” he often said. He is best remembered for his two “Old Time Barnyard Banjo Pickin’ ” albums, released by Starday in 1960 and 1963. In 1966 Starday also produced his “Salute to Uncle Dave Macon.” Singles included “Twenty Cent Cotton and Ninety Cent Meat,” “Wake Up Little Betty,” “John Henry,” and “Big One Got Away.” “Crazy Viet Nam War” was one of String’s favorites, as well as “Y’all Come.”

String signed with Don Light Talent after the colleges began asking for him. “When I play them big places, I call it ‘performin’. Otherwise, I just say I’m part of the show–and Lord help the other part!” String often said. In 1965 he performed at the University of Chicago and expressed amazement that students who once mobbed hillbillies with banjos, clapped for more mountain music.

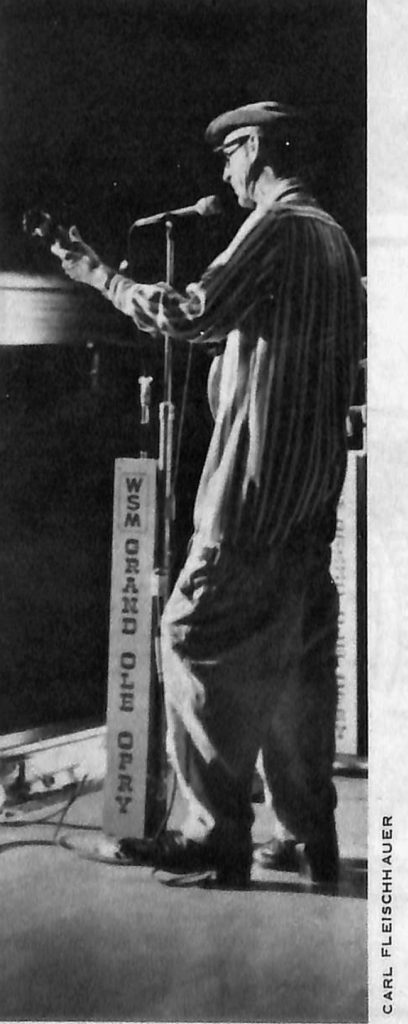

Part of String’s appeal to the college students was his claw-hammer banjo picking. Part of it was the unchangeable qualities in his life. Restless kids wanted stability. Stringbean seemed changeless. The world came and went. Other entertainers sported new images. Some switched from pop to country and back again. Duets split but String stayed the same.

During the last months of his life. String did hire a sideman, Curt Gibson. This simple change brought a lot of kidding from Opry friends. “String’s traded in his chauffeur,” they teased, knowing that String’s been driving him to performances all their married life, since he never learned to drive anything but his boat and tractor.

String’s only disappointment playing college dates was that the students preferred his overalls to his colorful one-piece suit of clothes.

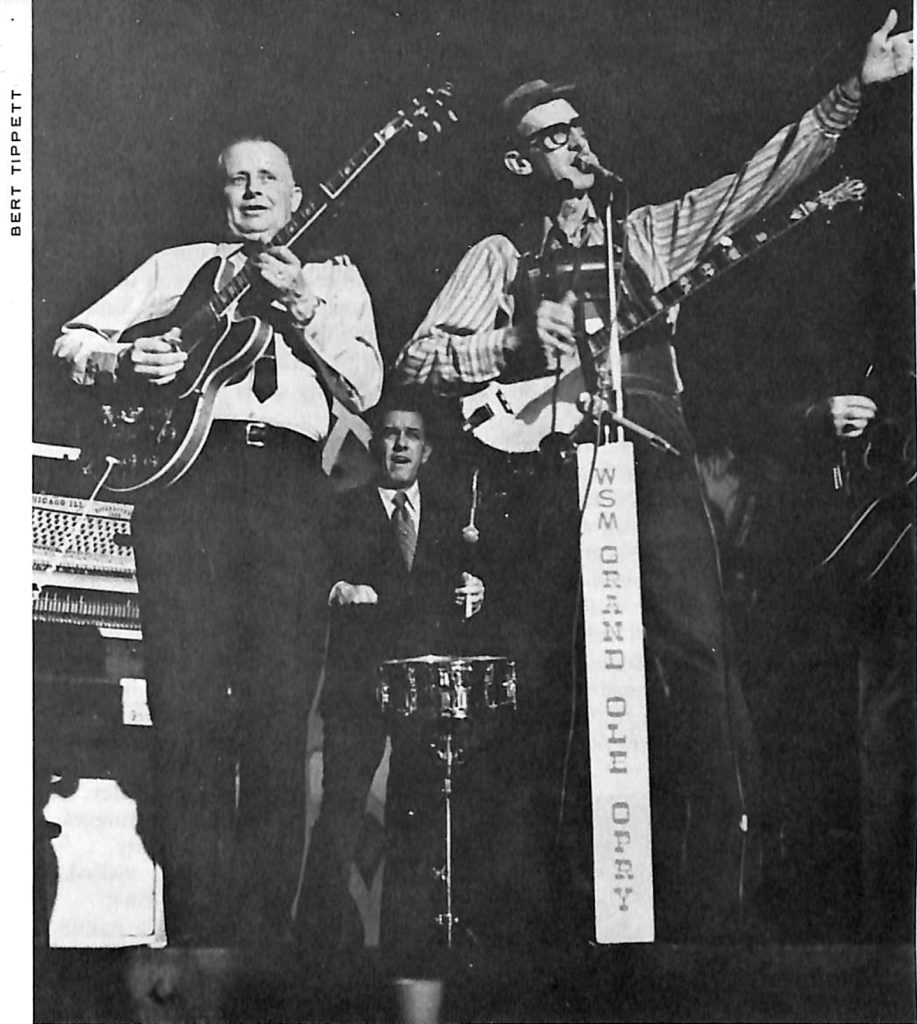

Besides his popularity on college campuses, String’s life was changed by Hee Haw. In the beginning, he was to play only a cameo role on the show which grew to be the Number One syndicated show in television. Soon, Producer Sam Lovullo and fans discovered that String’s humor was just right for Hee Haw’s format. They also found that String’s banjo picking, usually combined with Grandpa Jones and Roy Clark, was better than average, too. So each new Hee Haw year brought more parts for String. This fall, he and Grandpa Jones introduced a new fishing series.

Before Hee Haw policies prevented it, String appeared on almost all of the syndicated country music shows. A few years ago he played on the late “Pop” Stoneman’s show and admitted to “Pop” that this was a dream come true for him because he had admired the Stoneman talents for many years. In return, the Stonemans told String that bluegrass folks like his “Hot Corn, Cold Corn” better than any other of his original songs.

Undoubtedly, Uncle Dave Macon, “King of the Banjo Pickers,” influenced String’s life and playing style, as well as his comic banjo routine. String became Uncle Dave’s “godchild” and received one of Macon’s banjos at his death.

String’s familiar, palm-outstretched “how-do-you-do” gesture thrilled his audiences. His “heart, heart, heart, got it right next to my heart,” never grew old. Neither did his pulling the letter from his back hip pocket—“his heart”-fail to bring laughter.

String liked to look at the fingers of other musicians. Once pretty “Dancing Donna” Stoneman visited her sister Roni on the Hee Haw set. String took Donna’s little hands which have made her famous on the mandolin and turned them over and over.

“Where’s the callouses!” he asked, feeling her smooth finger tips.

“I don’t pick much anymore, String,” Donna told him.

“You can tell by the callouses. Yep. No callouses, you ain’t a-pickin’, String said.”

If that is true, String had a lot of callouses on his fingers and his funny bone which entertained thousands of fans for many years. But no matter how hard you looked at Stringbean’s heart, heart, heart-you never found a callous there.

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Stringbean! Such an important branch to the banjo tree. First heard him playing “ Mountain Dew” on the wonderful compilation album I was lucky to find in the early 60s -“The Bluegrass Hall and of Fame” on Starday…Thank you String.🪕