Home > Articles > The Archives > Doc_Watson_2

Doc_Watson_2

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

January 1978, Volume 12, Number 7

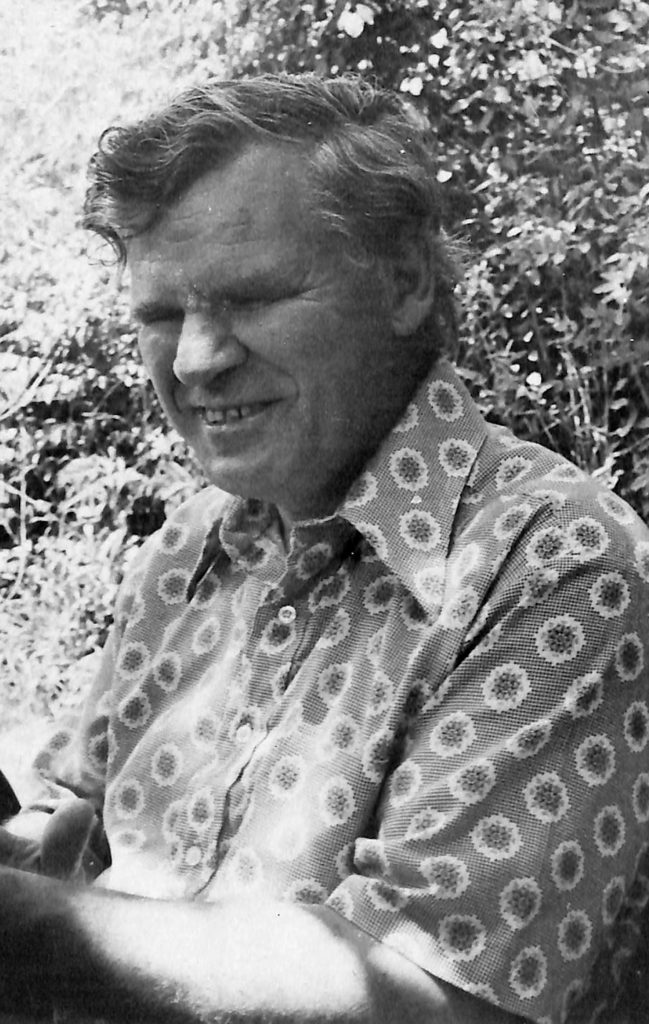

The hills of North Carolina have been alive with the sound of music for hundreds of years. Some of the greatest musicians have their roots in these hills, with two of those being banjo player Earl Scruggs and guitarist Doc Watson.

Ironically, I recently encountered Watson at a festival located only a few miles from where Scruggs was born and raised. The festival town was listed in the publicity as “Harris”, but you won’t find that on too many maps.

It is located just off Interstate 85, about half-way between Spartanburg, South Carolina, and Charlotte, North Carolina. Just down the road from the site of the “Third Annual Snuffy Jenkins Old Time and Bluegrass Music Festival” was the birthplace of legendary banjoist Scruggs. Although articles about Scruggs frequently list his hometown as Shelby, folks in that area will quickly tell you he actually is from a small community called Boiling Springs.

Festival promoter Ben Humphries rated the three-day event this year as a success. The Saturday night peak crowd hit roughly 5,000, which Humphries said was double the previous year’s. “I’m pleased with the turn-out, and I’m counting on having another one next year,” Humphries remarked.

Doc Watson showed up for his one-day appearance at the event more than two hours before he was scheduled to go on stage. Visibly absent from the Watson entourage was his guitar/banjo playing son, Merle.

After he had settled into a plastic-webbed lawn chair in a shady area just behind the stage, Doc explained the absence of Merle relating, “Every time we play Canada something happens. This time, just a few days ago, we were performing at an outdoor festival. Merle was walking on a path between the stage and the camping area when a German shepherd attacked Merle without any provocation. The dog went for Merle’s throat. Merle threw up his pickin’ hand to protect himself, and the dog bit Merle’s hand.”

Watson continued, “I’m not superstitious, but I have one more date in Canada scheduled and that will probably be my last. Just last year about this same time when we were up there. Merle was struck by a hit and run driver. When Merle saw the car coming, he threw out his hands and broke one wrist and fractured the other.”

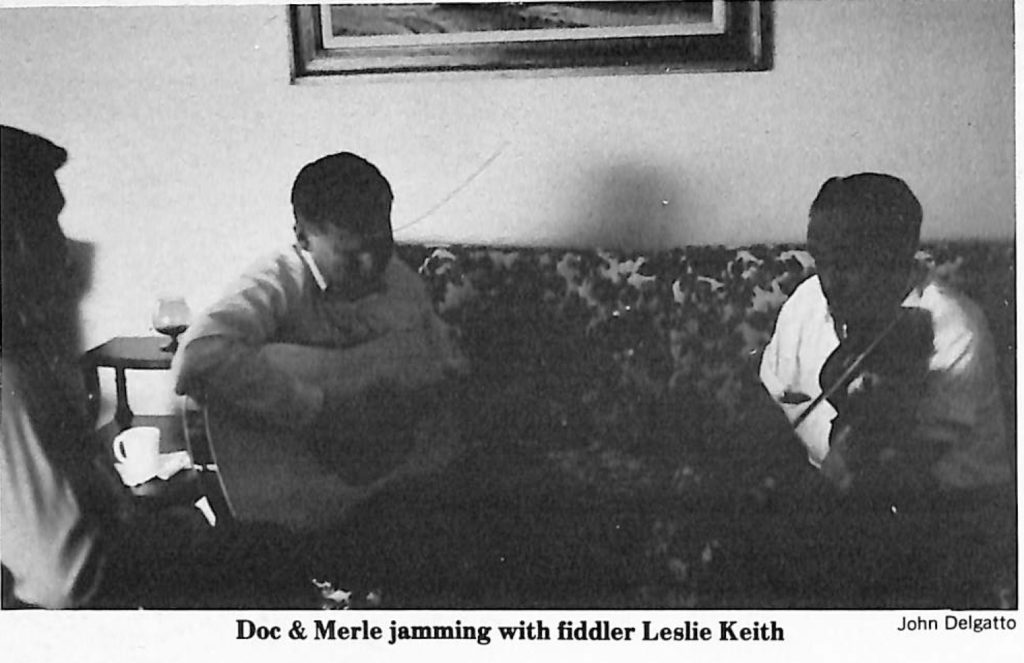

About this time a lady seated nearby asked, “Doc, are you going to play my favorite song, ‘I Recall A Gypsy Woman’?” Watson replied, “I don’t know. We ain’t got Merle to play slide.” He then turned to me and said, “I wish you would emphasize in your article Merle does 50 per cent of our lead picking, maybe more including slide.”

Throughout the time of our conversation, other bluegrass music acts were performing on stage only a few feet away from our chairs located just on the other side of the open-backed stage. The audience, however, could not see Watson because of the stage being some five feet above the ground area.

Watson apparently enjoyed the chance to be close to the stage to hear the other entertainers. At one point when Mac Wiseman told the crowd, “You’ve got a treat coming with Doc Watson. He’s here already.” Watson, who was consuming a luncheon plate, shouted back, “He’s back here eating!”

At another point, Wiseman was into one of his old numbers when Watson hushed my questions saying, “Let me listen to this song. I haven’t heard it in a long time.”

The pause gave me a chance to check up on my notes of Watson’s past. His great-great-grandfather came to America from Scotland and farmed land eight miles from Deep Gap, North Carolina.

When Watson was 11, he started his musical life by playing a fretless banjo his father had made for him. He had played the harmonica before that. His first guitar came about two years later, with that instrument being a $12 model. Watson already had learned some chords (“a C, G and a short F”) on a guitar he had borrowed from Paul Montgomery, a classmate at the Raleigh, N.C., School For The Blind. The first day he had his own guitar, Watson learned a Carter Family song, “When The Roses Bloom Again In Dixieland.” Besides the Carter Family, his early influences included Jimmie Rodgers, the Delmore Brothers and another blind guitarist named Riley Puckett.

It was about this same time, at the age of 13, his father taught him to have some incentive with his life. “He put me on the other end of a crosscut saw, and taught me I was more useful than just sitting in a corner.”

Between the ages of 18 and 25, Watson played wherever he could to make money, including playing on the streets near taxi stands. At the age of 19, he was still known by his birth name of Arthel until an appearance performing during a radio remote at a furniture store in Lenoir, North Carolina. When the band leader asked his name, Arthel told him, but the band leader said it was too hard to pronounce over the air. A girl in the audience shouted, “Call him, Doc!,” and the nickname stuck.

During the period from about 1952 to 1962, Watson played a Les Paul electric guitar in a country swing band. The group performed early rock, old standards and also country songs.

Watson’s family life in the early 1960s consisted of his wife, Rosa Lee, their son, Merle, and their daughter, Nancy. Fate caused him to cross paths about this time with Ralph Rinzler now with the Smithsonian Institute’s Performing Arts Division in Washington, D.C.

Rinzler, in turn, was instrumental in arranging a concert for Watson in New York, which in turn led to an appearance at the Ash Grove in Los Angeles. It was the Ash Grove appearance which resulted in Watson becoming a lead singer and group spokesman, due to the main lead singer and spokesman catching laryngitis.

My conversation with Watson resumed with this period in mind: When he was becoming a stage performer, but not yet well known. “I almost quit the road for good one time in 1963,” Watson recalled. “I was making $150 a week working in Philadelphia at the Second Fret Club. It was named after fret like to worry, rather than fret like on a guitar. My food and hotel costs were taking about $90 each week out of my pay. I told myself when I finished the week, I would be done with the road. Since I was not making any money and was lonesome and homesick, I was ready to give up. Except when someone came to get me to go to work, I was totally lost in that city.

“There was a 25-year-old black guy named Jerry Rix working in the kitchen of the nightclub, who learned of my situation. He told me, ‘Doc Watson, there’s a room in my house with a good clean bed, and it’s got your name on it.’ I told Jerry I would come home with him if he would let me split the money for groceries.”

“Jerry was a godsend. I lived like a king with him. It was a turning point in my life. When you help someone like that without thinking, you are doing it out of the goodness of your heart. I was encouraged by Jerry’s kindness to go on with my career. There were other times when I almost quit the road, but they were never as crucial as that time in Philadelphia.”

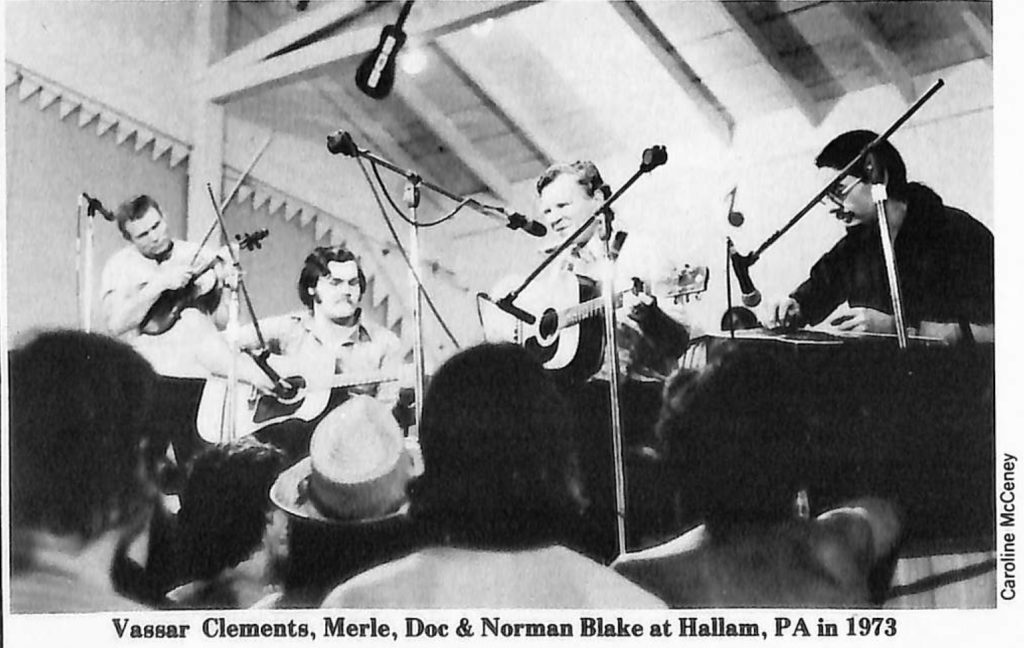

The same year as the Philadelphia incident, Watson established himself as a folk music performer after appearing at the Newport Folk Festival. Merle joined his father on the road in 1964. It was the success of the “Will The Circle Be Unbroken?” album with the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band that made Watson a true star in the music business. He estimates the album doubled his fans.

Watson today rarely finishes a concert without receiving a standing ovation. After singing folk songs for many years, he himself has become a folk hero.

I asked him if he ever repaid that kindness shown by the young man in Philadelphia. Watson recalled there was a young, blind girl in Nashville who was discouraged by her attempts at making it in the music business. “I told her before she got her hopes high and got them smashed, to think of the second best thing in the world she would like to do. I told her, ‘If singing lets you down, you can always fall back on that.’ She said she would like to interview people and write articles, and that is what she is doing now.”

While Mac Wiseman was on the nearby stage singing, “Letter Edged in Black”, Watson was backstage whistling the melody. He leaned over and said, “Man, I can hear some pretty licks in that one.”

Discussion of music led to talk of the great musicians from North Carolina. When I asked Watson if the area had something to do with the many performers from the state, he replied almost indignantly, “Listen, son, talent is something you’re born with. To develop it, however, lies from within the man. The area he comes from has nothing to do with it. It may, though, have something to do with the type of music he plays.”

When he was asked about being praised for his music. Doc replied, “I’m usually at a loss for words when I get super compliments. I always have the feeling of humility. I’m not trying to make a big name. I’m just working mainly for people’s enjoyment and to provide for my family. If you get honest compliments—not said to you but said to other musicians who pass it on to you—then those are the best compliments. I’ve always believed being yourself and not putting on airs is the simplest thing in the world to do as far as doing a stage show is concerned. Unless you are a pretty bad fellow, people will like you when you get on stage if you are close to what you really are.”

Watson said he tries to be cordial to all people he meets, but there are times just before and after each show he does not want to be bothered. “When you are on edge or are really tired, that sometimes is mistaken for conceit. But, when you do 30 to 40 minutes on stage, you put everything into it. You’re on edge, because it requires as much energy in one set of music as in half-a-day of regular work.”

In speaking of other guitar players, he praises Jerry Reed and Chet Atkins. “I have my own opinions about who are the best guitar players, but I don’t think there’s another guitar player who enjoys it as much as I do.”

Commenting further on stage performances, Watson observed, “Cleanliness and proper phrasing should be done in anybody’s music.” He said total involvement is an important aspect to a show. “If I couldn’t put my heart into it, I shouldn’t get up there,” he added.

His North Carolina home of Deep Gap offers a retreat from the road life. “Someone asked me what my hobby was, and I replied I didn’t have one unless it is being a handy man around the house. Not long ago when I had two electric pumps go out at both my old and new houses—located across the street from each other—I got me some pipe wrenches and fixed them myself. I used to do all the electric work at home, but I don’t anymore. I wired my whole stereo system in.”

Apparently to prove his ability around the house, Watson showed me some cuts on one hand “where my screwdriver slipped.” He also used to cut all the stove wood for his house with an axe. “It’s just precision guessing,” he explained of his method.

Watson was joined for his set by Cliff Miller of Asheboro, North Carolina, who was substituting for Merle. Miller also did the excellent sound for the Harris festival. Making a trio was Michael Coleman of Greensboro, North Carolina, on electric bass.

They opened the set with “Long Journey Home” and followed with “Deep River Blues,” “Tennessee Stud,” “I Recall A Gypsy Woman,” (the lady got her request) “I Still Miss Someone,” “Peach Pickin’ Time In Georgia,” “Last Thing On My Mind” and “T For Texas.”

People who praise Watson generally comment on his fine guitar playing and not his singing. The truth of the matter, however, is his voice is perfectly suited for the style he attempts to convey to his audience.

When one of the tunes was completed at the Harris festival—ending to loud cheers and applause—Watson leaned into his microphone and with his typical humility, said to Cliff Miller, “I appreciate that good pickin’. Cliff.” Then to the audience, Watson added, “He’s going to be as good a picker as he is a sound man.”