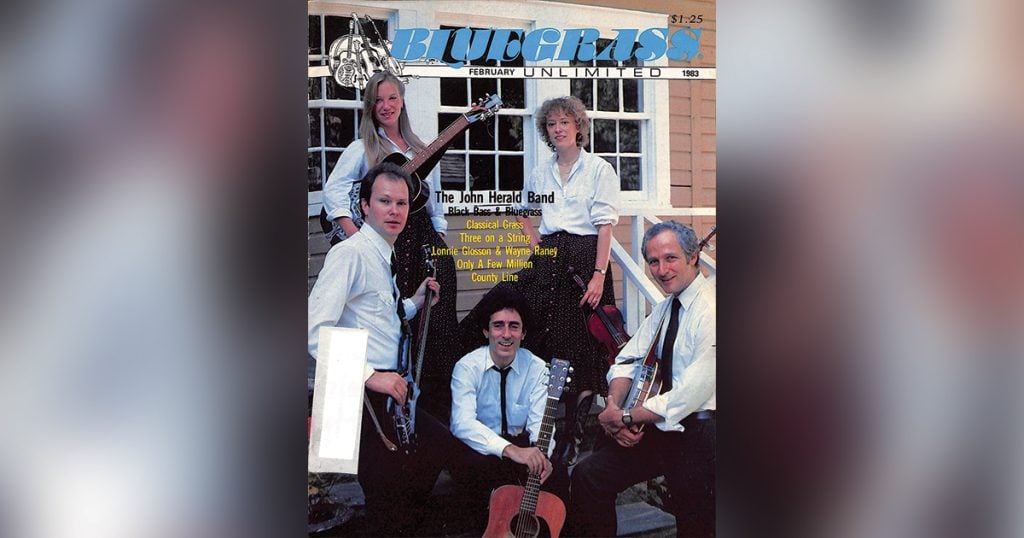

Home > Articles > The Archives > The John Herald Band

The John Herald Band

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

February 1983, Volume 17, Number 8

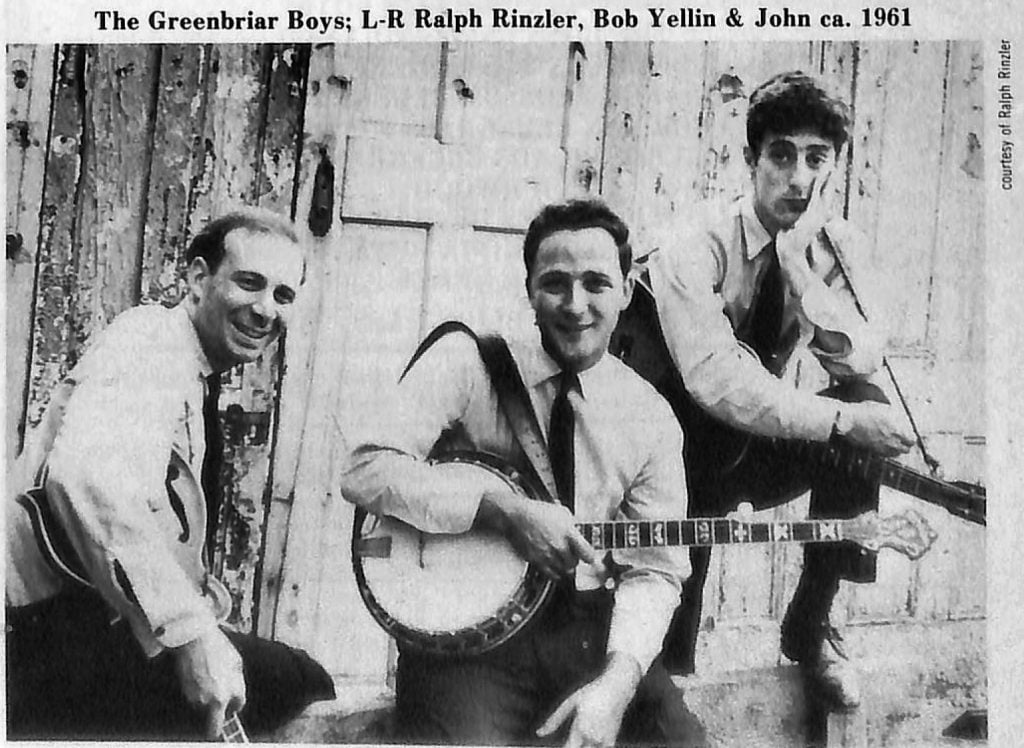

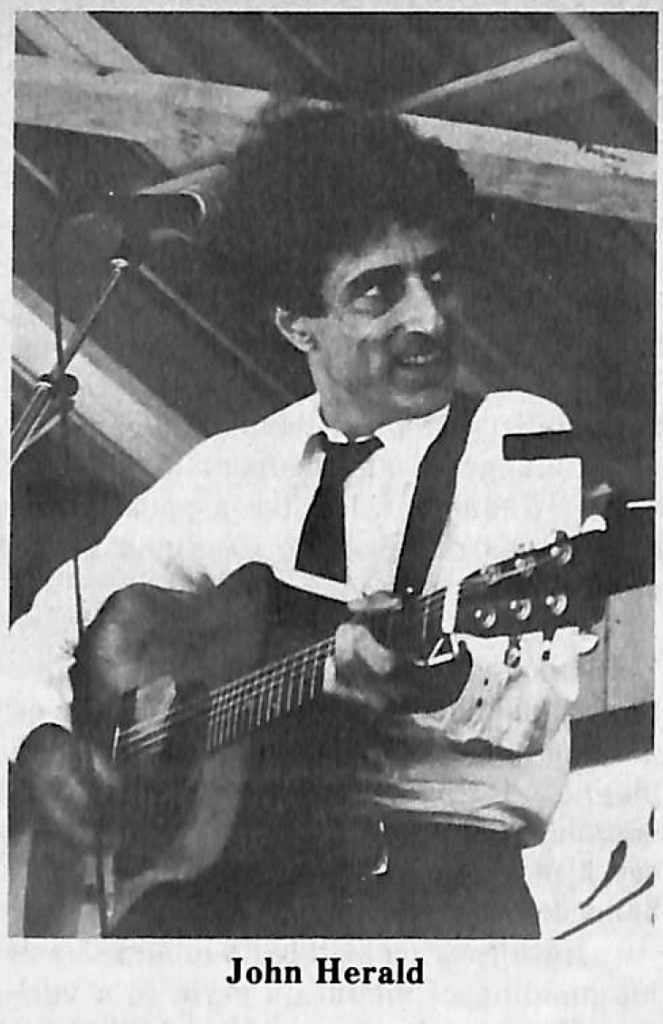

As the decade of the 1960s dawned, at the peak of a rediscovery of American folk and mountain music, John Herald found himself at the forefront of the movement as part of the critically heralded group called The Greenbriar Boys. Now—with a revitalized band joined with the force of former Greenbriar Boy Bob Yellin’s sparkling banjo, combined with two women performers on Dobro and fiddle, and a solid electric bass—Herald is making a bid for the fame that’s long seemed within reach of his wide-ranging voice.

Adapting a sound long known to southern mountain bands, but new to city ears, The Greenbriar Boys toured the country with such folk stars as Joan Baez and recorded several Vanguard albums still cherished by folk fans. The three-man unit broke up about 1967—widely recognized, but just short of major stardom.

Hitting the bluegrass and country circuit hard, the new John Herald Band was on the road throughout last summer’s bluegrass festival season. The group made stops all over the East, from New England to Virginia, honing a sound which Herald prefers not to categorize.

Developing a mixture of bluegrass, ballads, country, and a country blues- rock, the band owes much to the years Herald was out of the national limelight while playing with several bands and solo in the Northeast, as well as a period songwriting on the West Coast. The group also owes much to the diversity of its members—a mixture boosted by Yellin’s dedication to traditional style playing, mixed occasionally with playfully classical overtones of Russian and Israeli sounds slipping into his Scruggs- style banjo picking.

Just returned from 12 years living in Israel, where he had his own bluegrass band called “Galilee Grass” Yellin worked as an electronics engineer in a factory until accepting a similar high- level position in a New York City suburb.

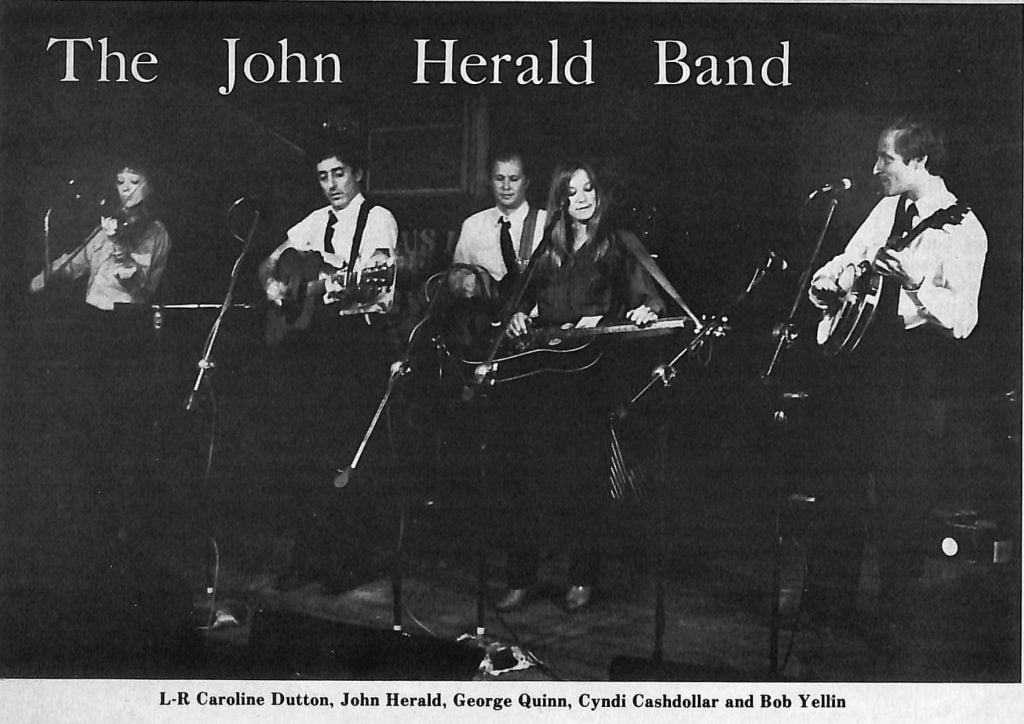

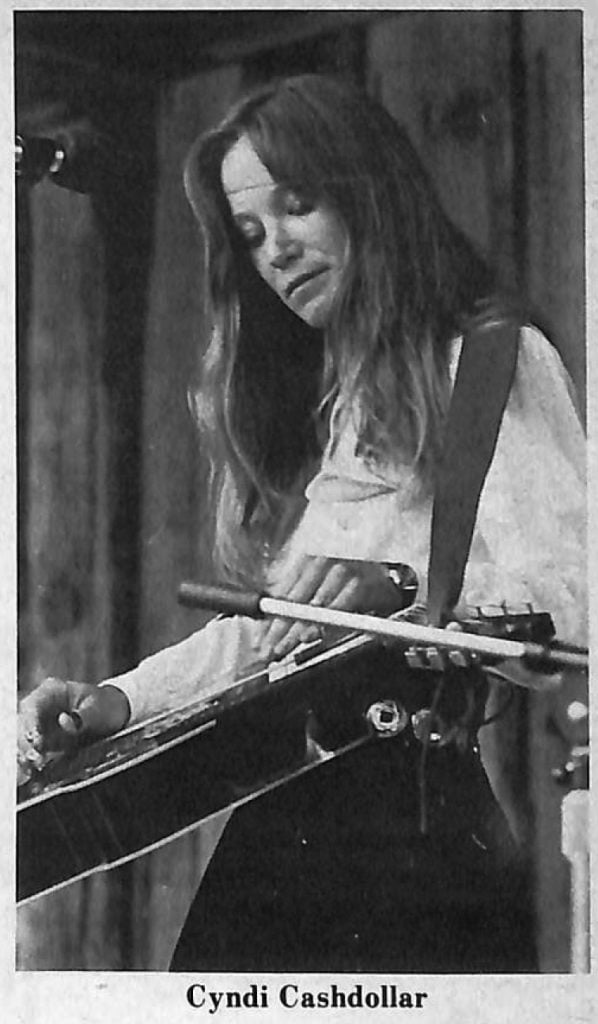

With a repertoire blending bluegrass, country, cajun, country-pop, country-rock, and ballads, Herald is relying on keeping different audiences happy. With Yellin’s banjo at his side, and backed by the classically trained fiddle of Caroline Dutton, the country Dobro of Cyndi Cashdollar and the electric bass of George Quinn, reaction at bluegrass festivals indicates Herald’s band is at home with traditional bluegrass tunes.

In refusing to be pinned to a single style, however, Herald believes in an approach that allows the band to play in “the whole country medium.”

“We’re not a bluegrass band —we’re an acoustic music band,” Herald said in a quiet interview at his small, secluded Woodstock, N.Y., home.

After the years of a more laid-back life while living partially on royalties from Greenbriar Boys’ songs like “Stewball” or “Up To My Neck in High Muddy Waters” (by himself, Yellin and Frank Wakefield) or “John the Generator” later cut by Maria Muldaur, Herald believes his latest band has become “a real force” which he hopes will break him into a wider audience than he’s known before.

“Probably since the Greenbriar Boys, this group is the best group I’ve been with,” Herald believes. “The people are very serious, they’re very nice, and they’re excellent musicians … We’re all going to be inspiring each other,” he said.

Since coming out of a nearly ten-year “semi-retirement” period which included what Herald now feels was a useful period of songwriting and playing with various well-known musicians on both coasts, the soft-spoken guitar player is taking a more businesslike approach to his craft.

Herald’s unusual vocal style is already unconsciously familiar to Linda Ronstadt fans who heard her nearly duplicate his treatment and arrangement of “Different Drum” on her hit single.

Finding writing “very hard” at first, Herald says he “started writing songs with some sincerity about 1966.” After moving to California for a few years in 1973, Herald learned to enjoy writing. Now, “I don’t feel happy unless I can write a large part of the week,” he said.

“In retrospect, California was a very good period,” he added.

“Once we do get a record company … they’ll have enough for two albums in all categories.”

Though Herald’s lead vocals were usually prominent 20 years ago in The Greenbriar Boys, that group (composed of Herald, Yellin and Ralph Rinzler, with Frank Wakefield, Jim Buchanan and Eric Weissberg associated at various times) all shared much of the singing. The new John Herald Band is distinctly John’s band.

With the exception of some vocal cooperation with Yellin, and occasional back-ups by other members, Herald’s piercing, yodel-like tones clearly dominate what is otherwise a mostly instrumental group.

The tight harmonies that have become hallmarks of some strictly bluegrass groups are not typical of The John Herald Band. The approach, though stylistically different, is not unlike the vocal dominance exhibited by a performer like Larry Sparks in The Lonesome Ramblers.

Herald is by no means a newcomer to the professional stage, but he shys from introductions as a folk “legacy”—“I don’t really want to be looked at that way,” he says. Though playing traditional and mountain music since his days in the University of Wisconsin in 1957 at the age of 19, Herald doesn’t like being treated with any special deference.

Geared to molding his new band, he cringes at the “legacy” approach, even if offered in respect. “I wouldn’t mind if they said, ‘Here’s a guy who’s been around since bluegrass, or acoustic music, first started getting famous … but if people know you’ve been playing 20 years, they treat you differently … they’re so polite,” Herald worries. “I don’t like being treated that way,” he said. “I like being treated as an equal.”

Full of energy on stage, Herald seems quiet and introspective in more private moments. Often he appears lost in contemplation in a personal corner backstage, his large dark eyes intent on some other place known only to him. Yet his lean, angular face is quick to smile when he spots a friend or meets a fan.

Interested to hear other performers, he’s apt to be found standing in the rain of an outdoor festival to hear someone he likes between his own sets, while many other band members stay sheltered.

New York City born, Herald spent much of his youth in the country. The son of an Armenian poet Leon Herald Sirabian, Herald spent much of his childhood at a progressive boarding school called Manumit in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. His mother, the former Dorothy Foster, died when he was only three, but passed to him the blood of another poet, John Greenleaf Whittier, from whom Herald traces his ancestry.

Though Herald does not claim any direct influence on his music from his father’s poetry, which he called “passionate, in the old country sense,” and very romantic and nostalgic—it’s hard to dismiss his poetic heritage when listening to some of the ballads he writes and obviously loves to sing.

In songs like “Warm Rain,” recorded by Herald on the Woodstock Mountains Revue “Back to Mud Acres” album, released in 1982, the poet’s romantic imagery is strong. (Woodstock Mountains Revue is a loosely defined collection of mostly acoustic stylists including banjo great Bill Keith, Happy and Artie Traum, John Sebastian, and others including John Herald, who has been on all four of the group’s albums on Rounder.)

On reflection though, Herald admits the circles his father travelled in, first as a professional poet, then as a chef in major Manhatten hotels, like the Waldorf, gave him the sense of the artistic life early. Even though his father was interested mostly in classical music, Herald recalls he took him to the early hootenannies featuring people like Pete Seeger during the late 1940s and the early 1950s when the folk music revival was just beginning.

It’s not hard to picture Herald at six or seven years old, tagging along behind his poet father—his wide, dark eyes absorbing the sights and sounds of city streets as the pair met with painters, writers and other artists his father knew.

Living part of his early youth in foster homes, Herald said he first really became interested in country music through listening to radio while at the Manumit School. He described the school as a converted farm turned into a school by Scott and Helen Nearing, who he says were “pioneers” in the ecological education and “back to the country” movements.

In childhood summers in the Woodstock area—a Catskill Mountain retreat long known for artists and writers, and now a haven for many popular musicians, Herald fostered a love for nature he is still cultivating. His years in California a few years after the 1970 breakup of his marriage to a Woodstock girl provided a respite, but did not fill his need for the lush greenery of the East. Exploring for edible plants in the forest is a major pastime for Herald—but the Florida Keys have become a new love, he says.

After spending most of the winter of 1981 near Key West, Herald said he hopes to spend part of his future there. “That’s my favorite,” he said of the Keys. “They’re a very exotic place, bursting with wildlife of all kinds.”

Herald, unlike Yellin or Caroline Dutton, had no formal musical training. He said he showed no particular interest in music until he became “very interested in blues” while in high school at Manumit.

“There were wonderful blues programs aimed at the black population of Philadelphia and Camden, N.J.” on the radio in Bucks County. Herald fondly remembers listening to people like Muddy Waters and Lightning Hopkins, as well as rhythm and blues groups that were the precursors to rock and roll.

He started an R&B group at school—then, in his senior year, he first heard bluegrass on a radio program out of Newark. Each day at noon, Herald said disc jockey, “Larkin Barking” Don Larkin did a country show featuring 15 minutes of one particular bluegrass artist.

“So I would race down to my dorm and turn on the radio to get 15 minutes of Red Smiley or Bill Monroe, and other stars in a form of music that has held a lasting attraction.

Between “Larkin Barking” and discovering WWVA in Wheeling, West Virginia, a lot of Herald’s friends at school “thought I was a real oddball for getting into that.” But later, Herald smiled to recall, “Don Larkin gave the Greenbriar Boys their first exposure to real country artists,” when, about 1958, the fledging ‘Boys opened shows for performers like the Louvin Brothers, Johnny Cash and Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs.

It was at the University of Wisconsin where the roots of Herald’s professional career found the enrichment that brought it to flower. There, in 1957, at the age of 19, Herald met banjoists Eric Weissberg (now famed for his “Dueling Banjos” arrangement for the movie Deliverance) and Marshall Brickman, who became a TV comedy writer.

“I followed them around campus like a puppy,” Herald says. A year later, Herald joined with Weissberg and Yellin in the first incarnation of the Greenbriar Boys. In 1959, mandolin player and musical folklorist, Ralph Rinzler, replaced Weissberg in the group.

Bob Yellin remembers the time well. It was in Washington Square Park in New York City, where Herald also used to go to listen to the folk music that was flowering in those more innocent days. Yellin was steeped in music—his mother was a concert violinist and his father was a music director. Yellin’s grandfather was a military bandmaster in Russia. In elementary school, Yellin studied violin, voice, piano and trumpet and in 1954, he graduated from the famed High School of Music and Art in New York City.

“About a year later, a girl friend of mine bought me a little ten-dollar, Kay banjo and I started to teach myself,” Yellin recalls. “Then one day I happened on Washington Square … on a Sunday, and heard Eric Weissberg, Roger Sprung and a few of those kind of people.” With the aid of his own musical ear and training, and a Pete Seeger banjo book, he made rapid progress. It was also about this time he met Johnny Herald in the park.

Yellin has a strong love of the bluegrass sound and the Appalachian Mountain banjo. Even after leaving the Greenbriar Boys in 1967 to tour Europe, Russia, the Middle East and the Far East as an electric lead guitar and banjo player in pop music groups and with the USO, he kept that love alive.

After settling in Israel in 1969, Yellin found like spirits and played a mixture of popular and Israeli songs in a bluegrass style during the 12 years he lived there. By 1980, he said his band, Galilee Grass, composed of five members including his wife Yona as a singer, had attracted enough popularity that it was set to make a record when he decided to move his wife, his teenaged son and daughter back to the United States and accept a high-level engineering position in a New York City suburb.

His job and the pressures of establishing his family in a new home as well as readjusting to life in the United States has somewhat limited the role Yellin is playing in the John Herald Band.

During the summer, Yellin traveled the bluegrass festival circuit and he said he intends to continue playing the major gigs. He is not ruling out a return to a full-time musical career, but with his background in physics and engineering job, the choice is not as feasible right now.

Meanwhile, Herald’s band is still honing a style after trying its blend of music on the summer bluegrass crowds. With the unusual presence of two competent and attractive women performers in Caroline Dutton on fiddle and Cyndi Cashdollar handling the attention-getting Dobro, festival audiences have been enthusiastic. John’s high-flying voice is the center of the new band, however, whether rolling in rapid-fire rhythm through a talking, poetic tribute in a song about city cowboy singer Rambling Jack Elliott—or the rollicking “Levee Breaking Blues,” Herald’s tenor stands out with its sudden rising and falling, amid his hard-driving, flat-picking guitar.

Doug Tuchman, Herald’s manager since August of 1981, encourages him to play a variety of song styles. Chatting at a record table at last summer’s Berkshire Bluegrass Festival in upstate New York, Tuchman said he told John to “Play your music the way you want to play it, and avoid the labels.” By playing different parts of his repertoire at different times, “the feeling is that John can appeal to different types of audiences,” he said.

In many respects, the band is still developing its direction. Herald is enthusiastic about its potential for various audiences. “The bluegrass idiom is a pretty definite, tight sort of thing,” he reflected … and he expects his band, “won’t be the standard thing you’ll see with all of the bluegrass bands.”

The lack of a mandolin doesn’t bother Herald since he has the sliding sound of the Dobro to take breaks along with banjo and fiddle solos. “I like Dobro because it sort of bridges that gap between bluegrass and country music,” he said. “It sounds a lot like a pedal steel, and yet its raw enough to give it some real good percussive, melodic flavor.” Also enjoying the Dobro sound, Yellin hopes to see the band continue in a traditional direction—at least as far as playing styles go. “I love the way John plays and sings,” Yellin said after the summer tours, but “I really would like to see a more traditional direction” as the band develops.

Recalling his own band in Israel, and his melding of mountain style to a variety of songs, Yellin explained, “I don’t mean the songs we’re playing, but how we’re playing them.”

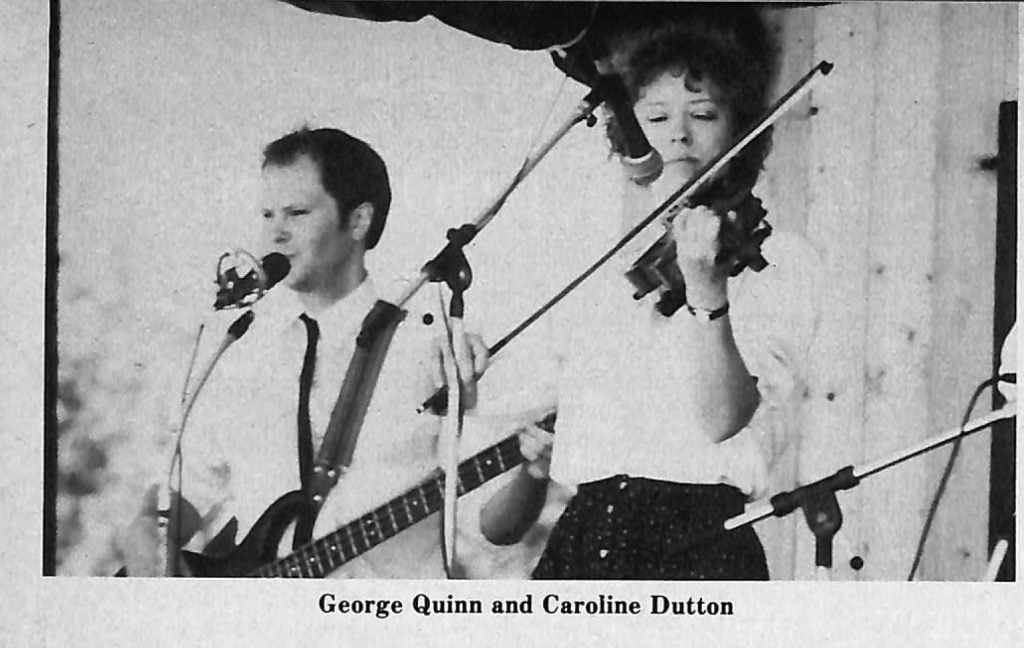

Caroline Dutton is an imposing figure on stage, standing with long legs planted firmly in cowboy boots and launching into bluegrass fiddle solos which sometimes betray her classical training with the complexity of the arrangement.

Growing up in Martinsville, Indiana, not far from Bill Monroe’s Bean Blossom land, Caroline says she never paid much attention to that traditional bluegrass showcase. Playing a violin since 4th grade that brought her to the all-state band in high school, then attaining a music degree from Western College for Women, Caroline didn’t start to play country music or bluegrass until moving to New York City with the intention of becoming a writer.

After working as a reporter for the Indianapolis Times for two years, then on a weekly called Park East in New York for five years, she says she didn’t play violin for five years until a boyfriend got her interested in playing country fiddle for a musical production.

That led to work in a variety of Manhattan clubs and then to a part in the on-stage band in Dude—a show she laughingly describes as a “million dollar failure” by the writers of Hair.

Other shows, including the more successful off-Broadway, Diamond Studs and performances with an old-timey band called Delaware Water Gap provided the violinist turned fiddle-player with her “first formal introduction to what country music was all about.”

A chance meeting with a Philadelphia club representative while she was playing the Charles Playhouse in Boston eventually led to a job with John Herald about 1977. Herald was living in Philadelphia at that time, and Caroline played with his band for about two years.

Leaving that group about 1979, she worked on orchestration in New York City for theatrical productions, films and T.V.

When John reorganized a band after casual performing with various personnel around Woodstock, Dutton rejoined the present group in 1981.

“It’s very exciting” playing with this band, she said. “John just gives such a powerful surge of energy when he plays … when we’re finished playing, we just ache.

“After all those years playing violin, now I have to play the fiddle,” she laughed, but memories of acceptance by long-time fiddle greats like Chubby Wise, during a jam at last summer’s Mineral, Virginia festival, and other events, have boosted her confidence, and she feels comfortable and confident of her ability to “synthesize my own style of bluegrass.”

A Woodstock native, Cyndi Cashdollar joined Herald’s band in 1981 after stints with various Woodstock bands, both in and out of bluegrass. She says country music has been her real love since she first heard it on the radio stations her father always tuned to.

Along with Caroline Dutton, she is also heard on several cuts on the Woodstock Mountains Revue’s “Back to Mud Acres” album.

Before joining Herald’s band, Cyndi also hosted a country radio show on WDST, the same Woodstock FM station on which Herald formerly hosted his own show, called “Drivin’ Country” for about four months. The band has also done several live performances on the mixed format station—joined at times by members of the Woodstock Mountains Revue.

Cyndi says she first began playing guitar about 1967 at the age of 11, with a year of lessons with noted banjoist Billy Faier. After hearing Ronnie Sutton, (another occasional member of Woodstock Mountains) play Dobro with a style so smooth he seems one with his instrument, she said she “got hooked on the sound.”

But it was Charlie Ferrara, another Woodstock musician who plays for the love of the sound, who taught Cyndi most of what she knows about Dobro.

“I learned more from him than anybody,” she said.

In love with bluegrass styles since hearing “Granny Does Your Dog Bite” (a mandolin number on a Seals and Croft album) Cyndi is not bothered by any fear the mixture of music played by the Herald band is not purely bluegrass.

In fact, “I would like to see the band even reach out more” and perhaps play “a little more swing.”

George Quinn, who plays electric bass with the band, is another Woodstock-raised musician with a background with a variety of local bands.

Working in his father’s ski shop in the Catskills in winter, George has spent much of his other time since graduating high school in 1968 doing stints with bands ranging from rhythm and blues in California, to a rock band with fellow Woodstocker Robbie Dupree on a three-month hotel gig in the Virgin Islands.

A fan of country music from hearing snatches of WWVA while traveling, George played for a while with a bluegrass band called Rent-A-Horse, along with Cyndi Cashdollar. Both Cyndi and Quinn joined up with Herald about the same time after that group broke up.

Now comfortable with the bluegrass bass style, Quinn says he’s “having more fun with the band now.” Though travelling five or six hours crammed in one car to make the festival rounds was admittedly tough to get used to, Quinn says he likes the festival atmosphere. With recent memories of hotel gigs in mind, “I enjoy playing out in the fresh air,” he said. •

Primarily self-taught, Quinn likes to experiment with different styles. Comfortable with the band’s sound, “I’m glad it’s not just straight-ahead bluegrass,” Quinn noted. “We can all add our own thing.”

The life of a band is at best an uncertain business, but in casting his lot within the country and bluegrass idioms, John Herald is confident his band is in a style that “has staying power.”

While enjoying pop music and rock, Herald thinks that style of music is “maybe in the worst state it’s been in” at present. Although he feels some so-called “new wave” music at least has an “intensity” that the current crop of stale pop and top-40 country he now hears doesn’t, Herald believes those styles lack an important ingredient present in more traditional forms.

“There’s no soul music now … it doesn’t provoke tears,” he said. “And I like to be moved to tears.”

In looking toward his future, Herald thinks, “The sky’s the limit… it just depends on what happens with musical trends in this country.” In choosing to stay within country bounds, Herald believes the trends are with him.

Last fall the group taped a one-hour television special at WLIW in Plainview, New York for PBS called “Blues Licks and Fiddle Sticks.” Also appearing on the show were John Hammond and Bill Harrell and The Virginians. The show is to be aired on 100 stations across the country.

Additionally, they have completed the studio work for their new LP, with musician-singer-songwriter John Sebastian as producer. Guest performers include Bill Keith and Larry Campbell, among others. Hopes are high that the record will be released by one of the major labels.

Syndication of a TV show planned for a New York City UHF station for national distribution on cable of UHF stations, is one avenue Herald is now exploring.

“Country music has hit,” he says. “I know most of my life, city people could not get into country music because they thought it was something uneducated. They had this Ma and Pa Kettle idea about the music … but now that they’ve taken to country music, perhaps the more traditional forms of bluegrass, old- timey, cajun, and some of those folkier types of country, acoustic music may have a chance.” he said.

“If that’s the way it bends, then perhaps we’ll be lucky.”