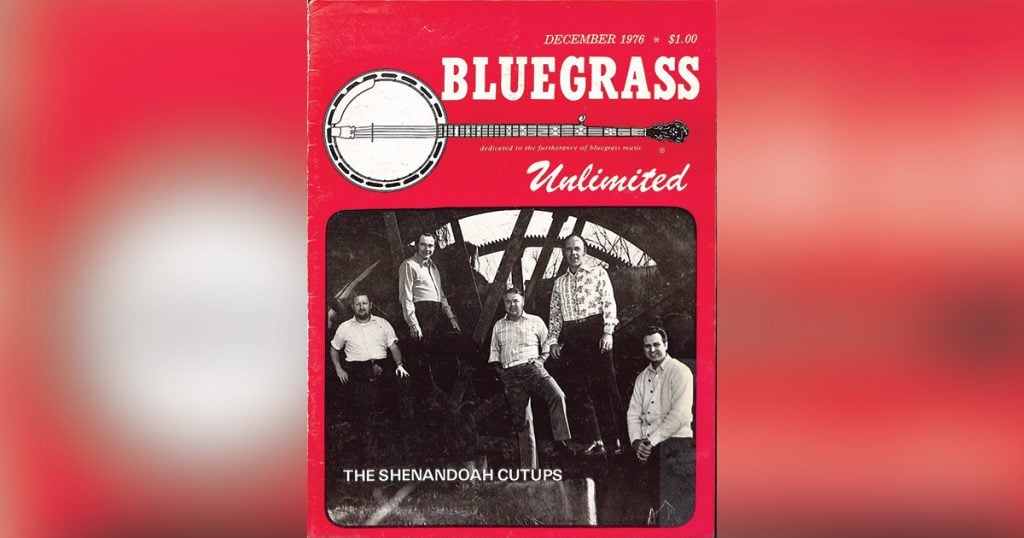

Home > Articles > The Archives > The Shenandoah Cutups: Classic Bluegrass From A Newer Group

The Shenandoah Cutups: Classic Bluegrass From A Newer Group

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

December 1976, Volume 11, Number 6

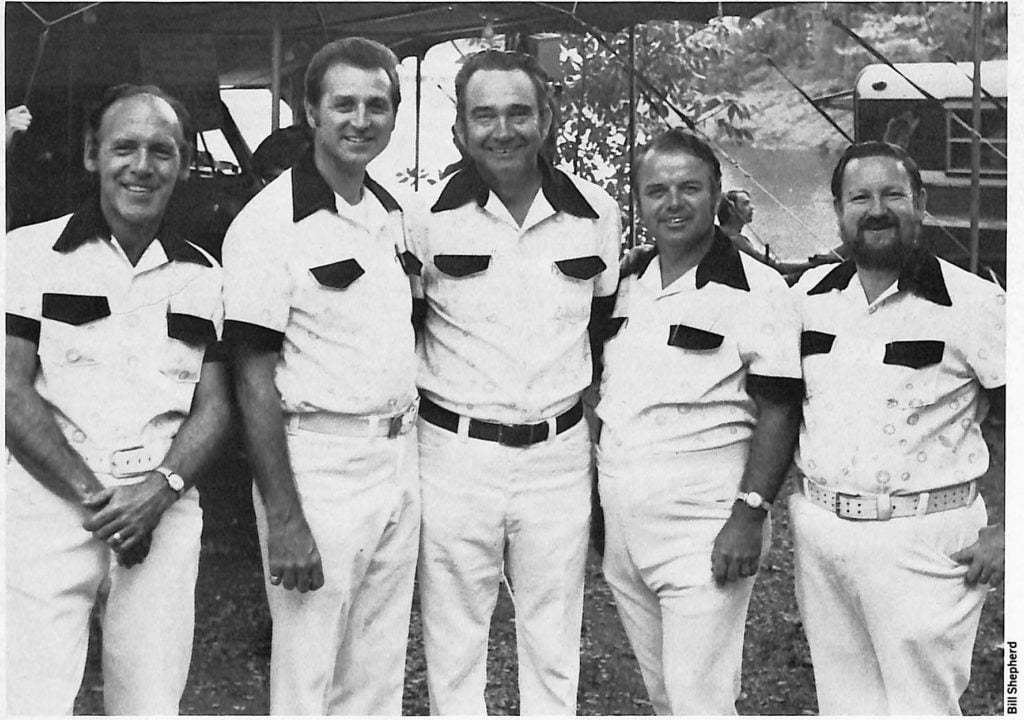

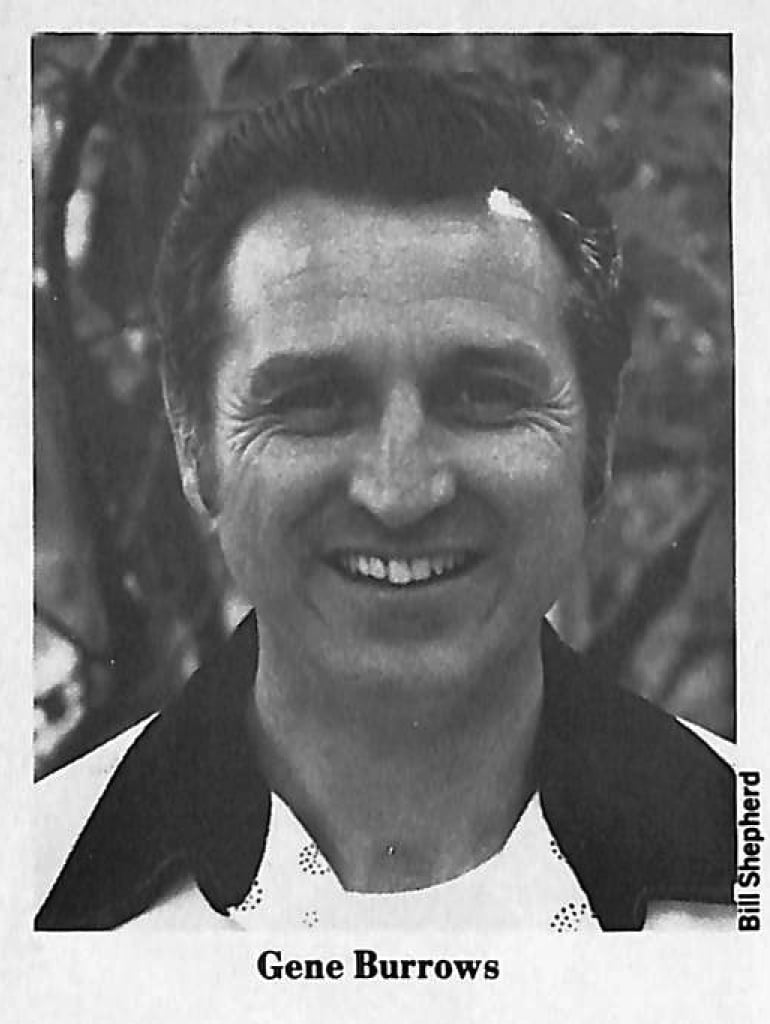

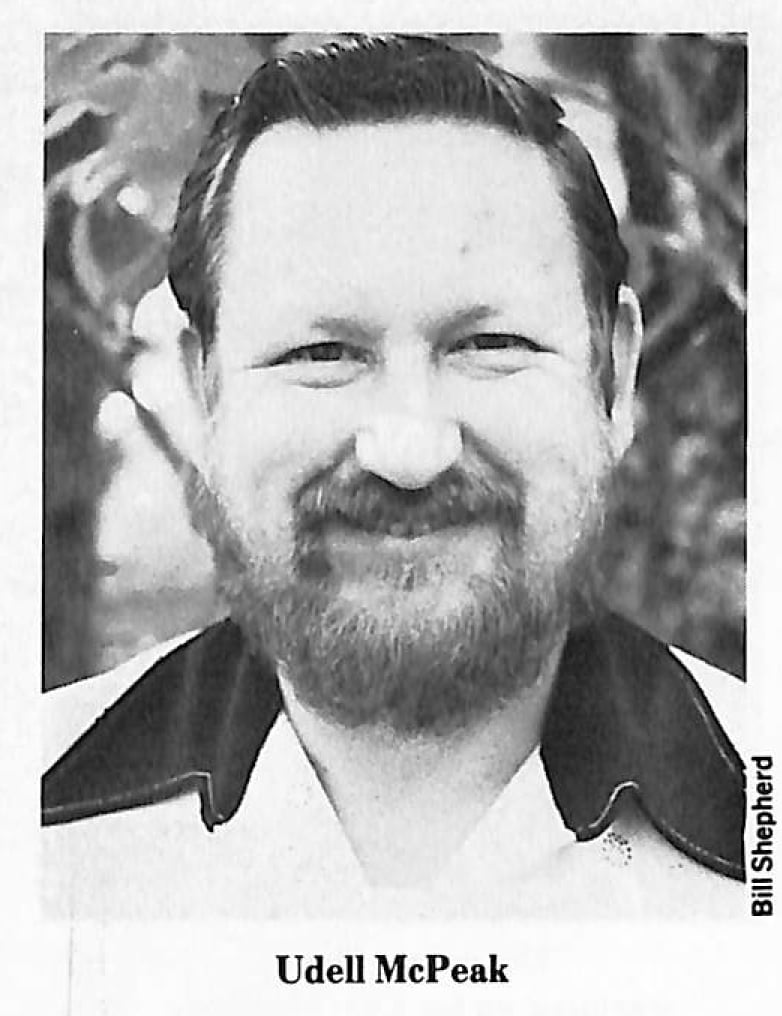

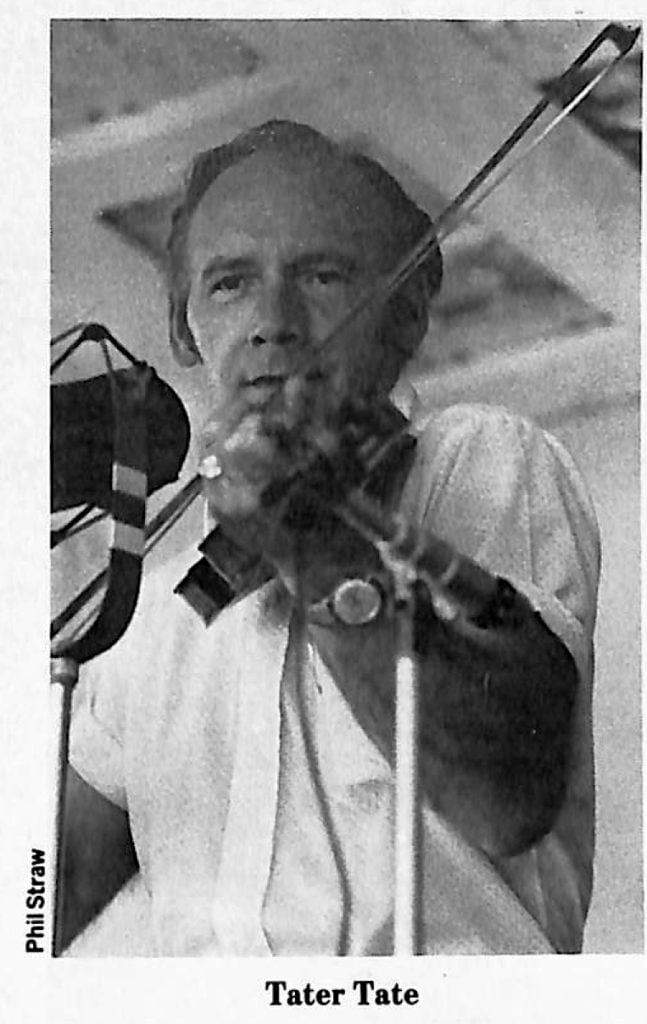

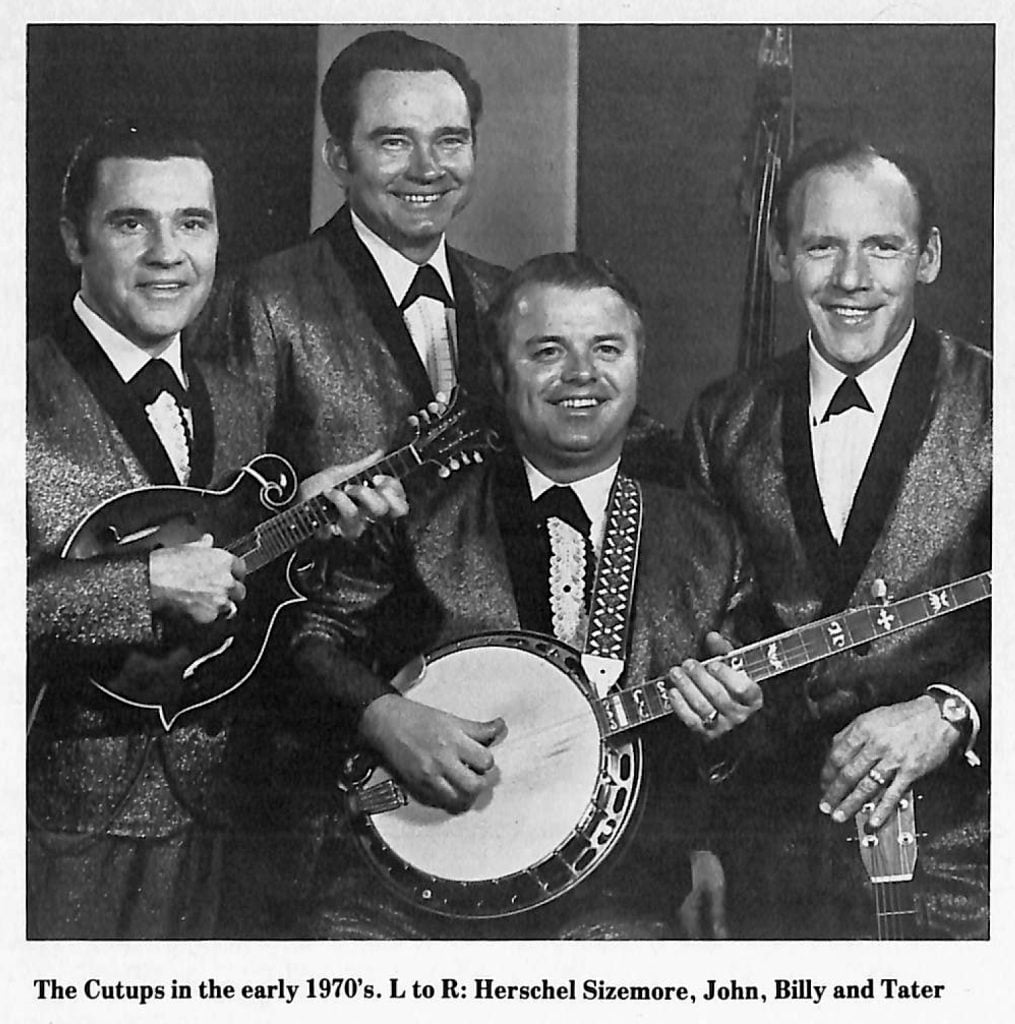

To those who appreciate most the superb classic bluegrass music of the late 1940s and early 1950s as exemplified by Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys, early Flatt and Scruggs, Reno and Smiley or the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers, few current groups arouse as much esteem as the Shenandoah Cutups. Composed of a quintet of musicians whose careers as sidemen date back to the early years of bluegrass, the sound of the Cutups conveys much to listeners reminiscent of those early years. Instrumentally, their music is best distinguished by the fiddling of Clarence (Tater) Tate, regarded by many as the best man around to have playing behind a vocal, the crisp, early Scruggs influenced banjo style of Billy Edwards and the solid bass fiddle work of John Palmer. Until the fall of 1973, the mandolin work of Herschel Sizemore contributed much to the group’s sound and is heard on all but their most recent records. Billy Edwards’ lead singing highlights the vocal sound and the band sports two of the finest tenor singers in the business today—Gene Burrows and Udell McPeak.

The core members of the group—Tater, Billy and John—have been together for the better part of a decade, the first three as members of Red Smiley’s Bluegrass Cutups, one of the finest bands of the mid-60s. The Smiley aggregation worked together on television as well as on the Wheeling Jamboree and on many early festivals and as a result of frequent play, pretty well perfected their music. When the TV show terminated in 1969, this core remained together and has continued to work the festival circuit and produce some excellent music.

A look at individuals within the group reveals their deep roots in both bluegrass and traditionally-oriented country music. Tater Tate, a native of Gate City, Virginia, has been active in bluegrass music for more than 25 years and has been a professional musician since working as a sideman for Archie Campbell’s group in 1948 at the age of 17. Even before that, Tater appeared on live shows and on radio with his family and as a regular on the Barrel of Fun show at Elizabethton, Tennessee. (The November 1973 Bluegrass Unlimited carried a lengthy article on Tater Tate; only brief highlights of his career will be repeated here.)

During the 1950s, Tate fiddled for lengthy stints with the Bailey Brothers, Carl Story and Hylo Brown, making records with all. For briefer periods of time, he played and recorded with Carl Butler and the Sauceman Brothers as well as spending two years in the U.S. Army. For about three months in 1956, Tater worked with Bill Monroe’s band but did no record sessions with him. Many of the groups Tater played in worked at the Wheeling Jamboree or at WNOX and WROL in Knoxville.

In the early 60s, Tater worked and recorded with Bonnie Lou and Buster Moore, Carl Story and Jimmy Martin. He fiddled again with Carl Sauceman and did extensive television work at Knoxville’s Cas Walker Show together with the Brewster Brothers and Claude Boone. In October 1965, he moved to Roanoke where he became the third and last fiddler with Red Smiley’s Bluegrass Cutups with whom he waxed four vocal albums and also cut four fiddle albums.

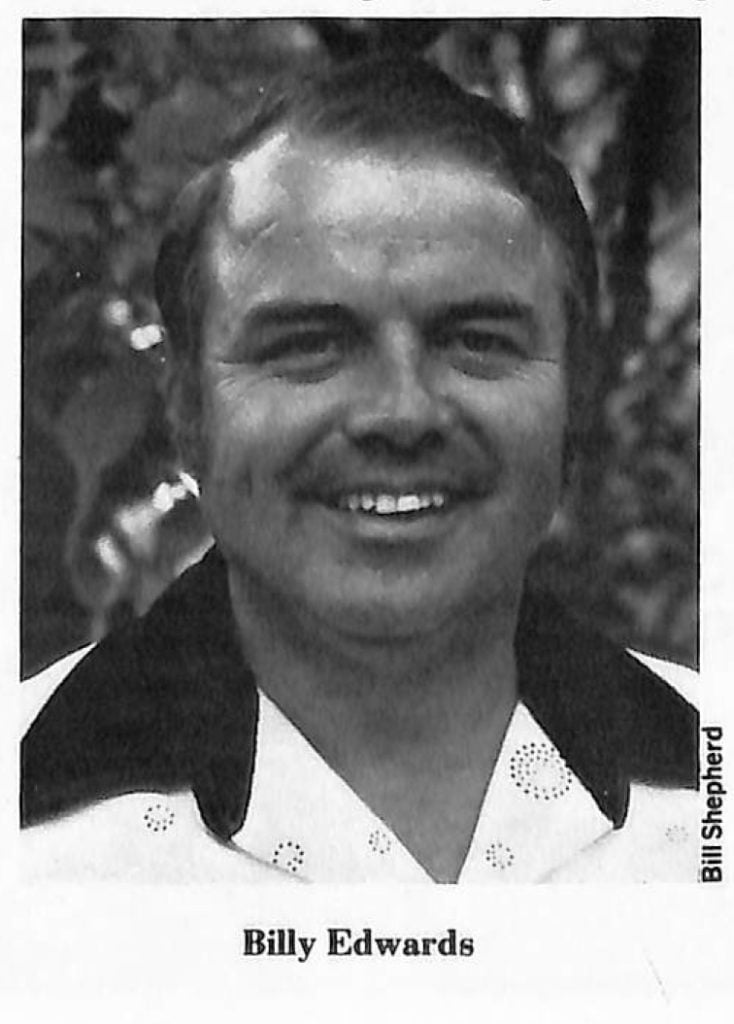

Billy Edwards had extensive experience in bluegrass music before coming to the Cutups. Born in 1936 in Tazewell County, Virginia, Billy worked on radio at WHIS Bluefield, West Virginia from childhood and from 1955 through 1958, he played banjo and sang with Cousin Ezra Cline’s Lonesome Pine Fiddlers at WSLI in Pikeville, Kentucky. He later worked with Cecil Surratt and Smitty Smith, Melvin Goins and Jimmy Martin. Based at High Point, North Carolina in the early 1960s, Billy worked with such groups as the Friendly City Playboys and the Sunny Mountain Pardners before coming to Roanoke in July 1966 to join the Red Smiley band. (More details on Billy Edwards can be found in the November 1974 Bluegrass Unlimited).

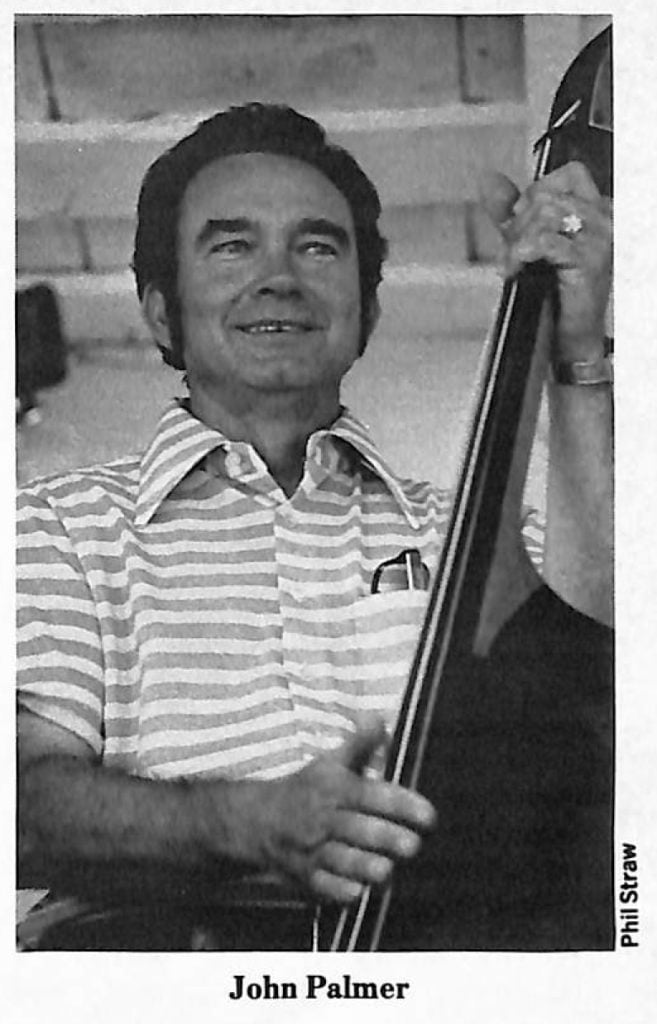

John David Palmer, the only non-Virginian in the current band, came from Union, South Carolina where he was born on May 28, 1927. He spent his early years on a farm and went to work in a cotton mill at the age of 16. John’s first serious interest in music developed from a neighbor, Mack Woolbright, a blind musician and one-time member of the old Columbia recording duo of Parker and Woolbright. The old musician taught John the fundamentals of both the guitar and bass fiddle. John then joined a local group, the Pea Ridge Pioneers and played daily radio shows at Spartanburg, South Carolina and personal appearances until entering military service.

After his Army career terminated, John and Don Reno worked a lot together on local talent contests and radio shows thus making them the original Tennessee Cutups. Then Don went on to play professionally with Bill Monroe, Tommy Magness and Arthur Smith. In the early 50s, Don Reno and Red Smiley began to record for King Records. Contrary to an oft-repeated statement, John did not play bass on every record Don Reno and Red Smiley ever made since he missed the early sessions on King as well as those made after Red rejoined Don in 1971. However, he did play bass on all the material made between April 1955 and their breakup in October 1964. He also toured with them, played at the Old and New Dominion Barn Dances at WRVA and on the daily Top O’the Morning Show at WDBJ-TV in Roanoke. When the duo separated, John remained with Red at WDBJ-being the only member of the group to do so.

Gene Burrows became another early member of the new Red Smiley band. Gene, born in Bedford County, Virginia on September 12, 1928, first fell in love with what evolved into bluegrass music when his family brought home an early Monroe Brothers record when he was only eight. Gene retains possession of the record to this day—the old Bluebird classic of “Feast Here Tonight”/“Goodbye Maggie”. Gene began playing music more actively at 16 and soon joined a group on WDBJ Roanoke, the Tinker Mountain Boys with whom he worked for several months.

From the mid-50s through the early 60s, Gene headed a local group in the Roanoke area known as the Sunny Valley Boys. During much of this time, Gene appeared on the Reno and Smiley TV show and subsequently became a regular member of the Bluegrass Cutups singing tenor and playing rhythm guitar or mandolin and working on Red’s Rimrock and Rural Rhythm albums.

When Gene left the Cutups in 1968, another musician of long and varied experience replaced him. Udell McPeak, a native of Wytheville, Virginia where he was born June 12, 1935, also sang tenor while playing rhythm guitar or mandolin. Udell, the oldest of the four musical McPeak Brothers (the others being Dewey, Larry and Mike; see Bluegrass Unlimited, January 1976) first became acquainted with bluegrass in the late 40s but recalls being more interested in country singers like Hank Williams and Red Foley. About 1949, he first heard the Blue Sky Boys during their stint at WCYB Bristol and developed considerable appreciation for them. A few years later, he became attracted to the Louvin Brothers and for a brief time, the duet styles of Charlie Bailey and Bob Osborne. Udell first sang on radio at WYVE in Wytheville about 1949. He remembers that he and a friend sang a duet and as it was summertime, he played the show barefoot.

Later Udell went to WCYB and played with Ralph Mayo and the Southern Mountain Boys and at WFHG also in Bristol with Jimmie Williams and the Shady Valley Boys. Both Mayo and Williams eventually achieved more fame as Stanley Brothers sidemen than as leaders of their own groups. In 1955, Udell joined Cousin Ezra Cline’s Lonesome Pine Fiddlers in eastern Kentucky. Melvin Goins soon left the group and Billy Edwards came in to play banjo and sing lead. Billy and Udell developed an excellent duet which unfortunately never was recorded. The only recording the Fiddlers performed during this period came when Billy, Udell and Curly Ray Cline helped Hobo Jack Adkins record a session of four songs on Starday records. Udell entered military service in April 1958 and after his release, played very little professionally in the 60s. He and Dewey first formed the McPeak Brothers as a local group during this period and he and Billy Edwards performed at some fiddler’s conventions where Folkways recorded one of their duet numbers.

As members of the Red Smiley band, Tater, Billy and John assisted at several recording sessions as well as making albums of their own. John had already helped Don Reno and Red Smiley back up Rose Maddox on her famous bluegrass album for Capitol in 1963. John, Tater and Billy helped Lee Moore, Hylo Brown, J. E. Mainer, Shot Jackson and Jim Eanes make albums for Uncle Jim O’Neal’s Rural Rhythm label. Gene helped out on the Mainer and Eanes albums.

In the spring of 1969, WDBJ-TV terminated Top 0’ the Mornin’ and Red Smiley decided to retire from music. However, Tater, Billy and John chose to keep the group together. Jim Eanes, a veteran country and bluegrass vocalist who had once recorded for such major labels as Capitol, Mercury, Decca and Starday, came in to emcee and sing lead. Jim played only during the 1969 season with the group during which time their name became the Shenandoah Valley Cutups—an amalgam of the old Eanes band, the Shenandoah Valley Boys together with the more recent Bluegrass Cutups. With McPeak departing, the recruitment of Alabama’s Herschel Sizemore rounded out the group.

Sizemore constituted a key member during his more than four years with the Cutups as mandolin playerand tenor singer. A veteran of several years of bluegrass picking in the deep south was closely entwined with that of his long-time friends, Jake Landers and Rual Yarbrough. Together with Vassar Clements, this trio made up the Dixie Gentlemen, an outstanding bluegrass band of the early 60s. This group eventually recorded six albums together although their name appeared on only three. Their Dot album with Tommy Jackson was released under the famous fiddler’s better-known name and two albums on the Time label bore the pseudonym of Blue Ridge Mountain Boys. In addition to his extensive work with the Dixie Gentlemen, Herschel worked some with Bobby Smith’s Boys from Shiloh and for a year with Jimmy Martin’s Sunny Mountain Boys.

During their first year, the Cutups recorded twice together. The first, a Jim Eanes country album on Rural Rhythm contains material of limited interest to bluegrass fans. The second, on County as the Shenandoah Valley Quartet which featured Billy singing lead on ten numbers and Jim on four, is one of the better bluegrass gospel albums of the last decade.

After the departure of Jim Eanes, a variety of persons worked with the Cutups as the fifth member. In the spring of 1970, Cliff Waldron, whose partnership with Bill Emerson had recently terminated, worked with them for a few weeks before returning to the Washington area and forming his own group. Udell McPeak also worked with them on a part-time basis and Wesley Golding, currently of Boone Creek, played guitar and did some singing through two summers. Often the band had only four members which forced Tater to abandon the fiddle and play guitar.

During the early 1970s, the cutups appeared at all the major festivals. They played Bean Blossom twice and at virtually all of Carlton Haney’s Berryville and Camp Springs showcases as well as at Mac Wiseman’s Renfro Valley. They have also been on most of the other large festivals at least once and on many of the smaller ones in addition to a few college dates. In the first year, they played often at WWVA and occasionally since. Mac Wiseman played an important role in assisting with bookings in his last year at Wheeling and subsequently the Cutups have nearly always backed Mac whenever they appeared on the same billing. In the past year, they have also recorded with the legendary “Voice With the Heart” on both the CMH and Vetco labels.

In early 1971, the Cutups recorded an album on the Major label which included several songs written by Pete Gobel of Detroit who penned several chartmakers for the Osborne Brothers on Decca. Unfortunately, Gobel’s songs never took off quite as well for the Cutups. Of more interest to the traditional bluegrass fans who make up the bulk of their boosters was a single release on County of “Beneath the Winter Snow”/“Swingingsa Nine Pound Hammer” and an album with Curly Seckler on the same label which is one of the better—albeit underrated—albums of recent years.

In October of 1971, the Shenandoah Cutups recorded the first of five albums on Paul Gerry’s Revonah label. The first, entitled Bluegrass Autumn, turned out to be a fine album of traditional bluegrass. A year later, the group waxed two more albums on the same label, The Shenandoah Cutups Sing Gospel and Traditional Bluegrass. Larry Hall and Clinton King of the Virginia Mountaineers assisted on guitar at this session giving Tater more opportunity to play fiddle.

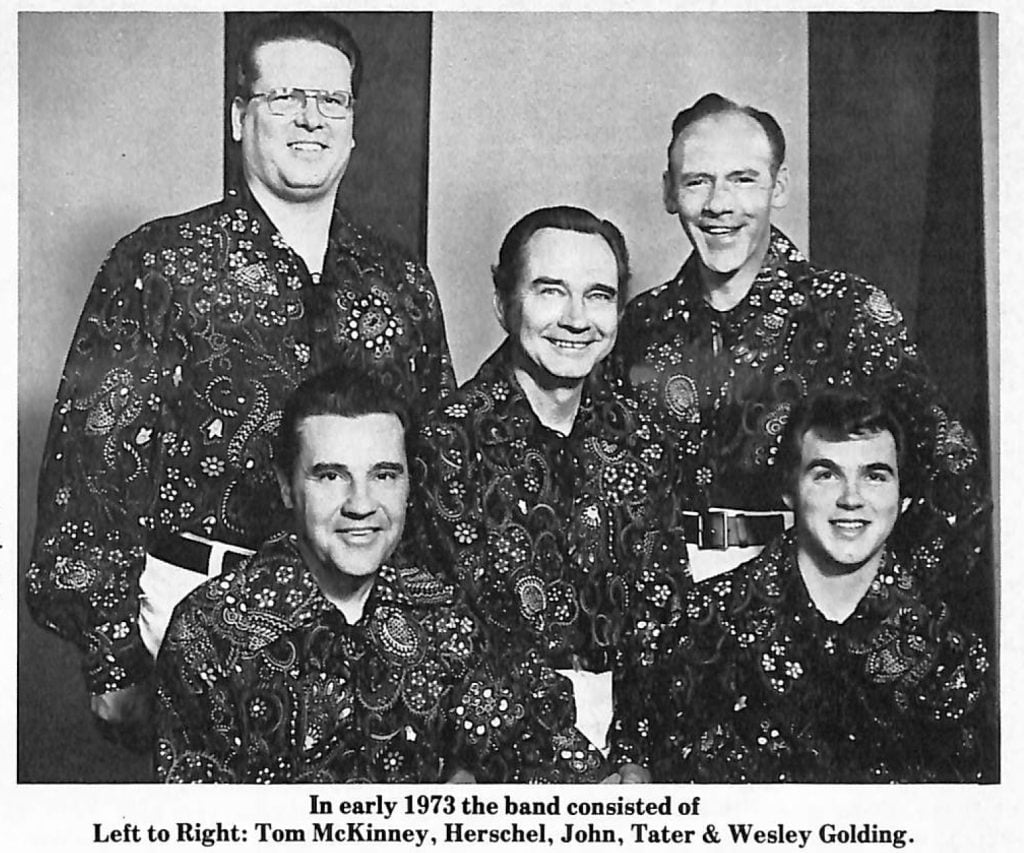

In 1973, the Cutups went through their only season of noteworthy personnel changes. Shortly after the recording of the second and third Revonah albums, Billy Edwards decided to drop out of music for a time during which period Tom McKinney of Asheville, North Carolina ably handled the banjo playing. Billy’s singing proved more difficult to replace with the result that the group’s Rebel album cut in the spring of 1973 featured a somewhat different sound with Tom and Wesley Golding handling much of the vocal load. Although less traditional in sound than their County and Revonah efforts, the Rebel did contain some good new songs, particularly Wesley’s “Stillhouse Hollow” and probably Tater’s best rendition of his most requested number—“Black Mountain Rag”.

In the fall of 1973, Billy Edwards returned to the Cutups, just prior to the departure of Sizemore and Golding who subsequently organized the Country Grass. Gene Burrows then returned to the group on mandolin. During the five years he had been out of bluegrass. Gene worked with the gospel singing Dominion State Quartet with whom he helped record three albums. Udell McPeak also came back to handle guitar duties. The presence of these two men plus Edwards gave the Cutups three of the best vocalists in bluegrass. Although Billy continues to handle the bulk of the lead singing. Gene and Udell also have their solo numbers and the duet of Billy and Udell is one of the finest in bluegrass today as is shown by their performance on the group’s fourth Revonah album, Tribute to the Louvin Brothers. Their rendition of such gospel songs as “Nearer My God To Thee” and “No One to Sing For Me” have brought praise from such fellow musicians as Sonny Osborne who requests them to sing the latter number with regularity at festivals wherever they all appear. The Cutups fifth and most recent Revonah album, Bluegrass Spring, also shows them at home on a variety of traditional bluegrass numbers.

The instrumental stars of the group— Tate, Edwards and Palmer—continue to be in demand for recording sessions. In recent years, Tater has helped the Bailey Brothers on Rounder and on a fine gospel album by Larry Richardson, while Billy played banjo on an album by the Conner Brothers. The three have backed Bill Clifton and Red Rector on County and the past winter they helped Mac Wiseman cut a two album set on CMH and two albums on Vetco. These sets with Mac all contain some twin fiddling—Tater and Arthur Smith on five CMH cuts and Tater with the fine former Goins Brothers sideman, Buddy Griffin, on the Vetco efforts. After the fine work of the Cutups with Wiseman on festivals for so many years, fans of both can hardly be less than pleased that they have finally gotten to record together.

This writer, a long-time admirer of the Shenandoah Cutups, recently held a lengthy conversation with Udell McPeak, one of the group’s two newer members. Udell, whose witty off-stage remarks have long been a delight to those fortunate enough to hear, made some serious observations on the direction of bluegrass. Although interrupted by a fan who mistook him for Nashville’s Ralph Emery, Udell contended that he believed traditional bluegrass to be in resurgence. The trend to progressive styles seem to have leveled off and groups like the Cutups are more than holding their own. The bearded gentleman concluded, “traditional bluegrass is moving up and the Cutups are moving with it”.