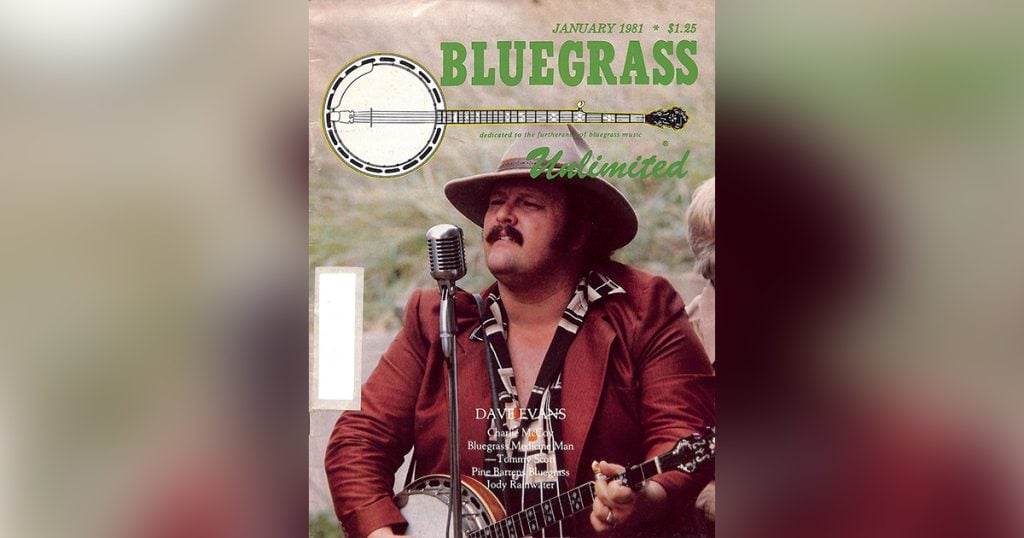

Home > Articles > The Archives > Dave Evans—The Voice of Traditional Bluegrass

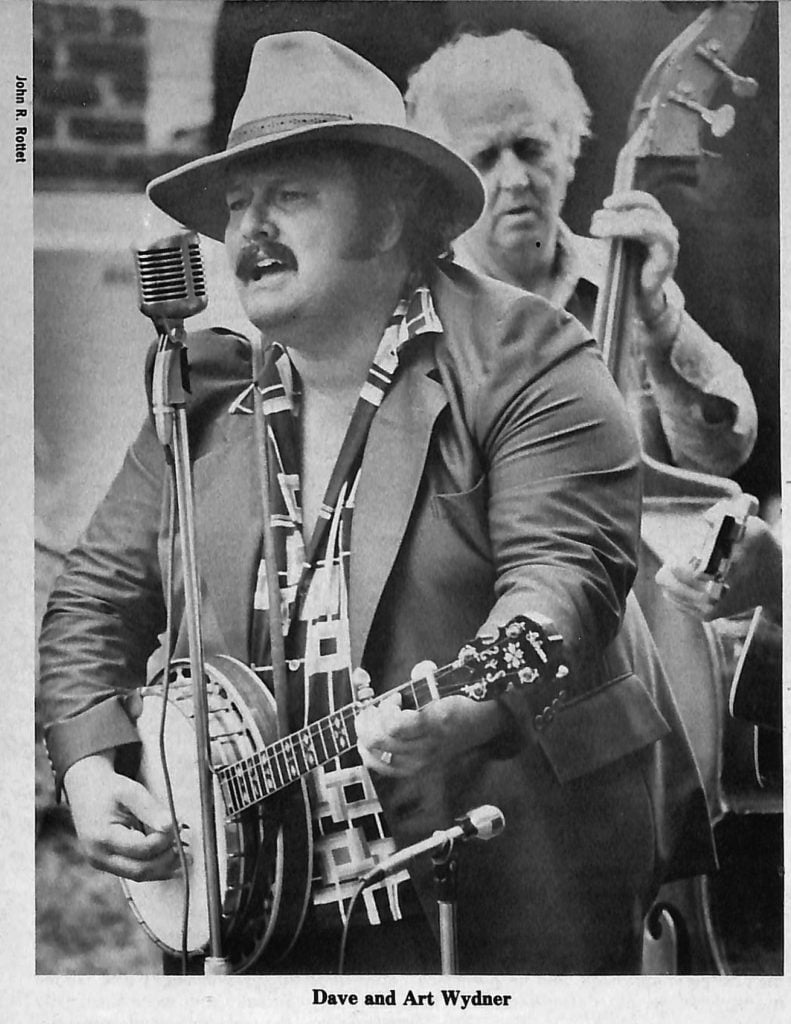

Dave Evans—The Voice of Traditional Bluegrass

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

January 1981, Volume 15, Number 7

The song on the radio was barely audible over the din of our bluegrass party, but there was something unusual, something “extra lonesome” in the voice filtering through the room that made you stop and listen. The power and intensity were enough to impress any longtime fan of the Stanley Brothers or Larry Sparks, and as the melody soared to spectacular heights we wondered aloud, “Who the heck is this guy?”

At the song’s end the DJ mumbled the name “Dave Evans,” then faded into the room noise without any further clues about the title, source or vintage of what he’d just played. I made a mental note to remember the name Dave Evans and find out more about him.

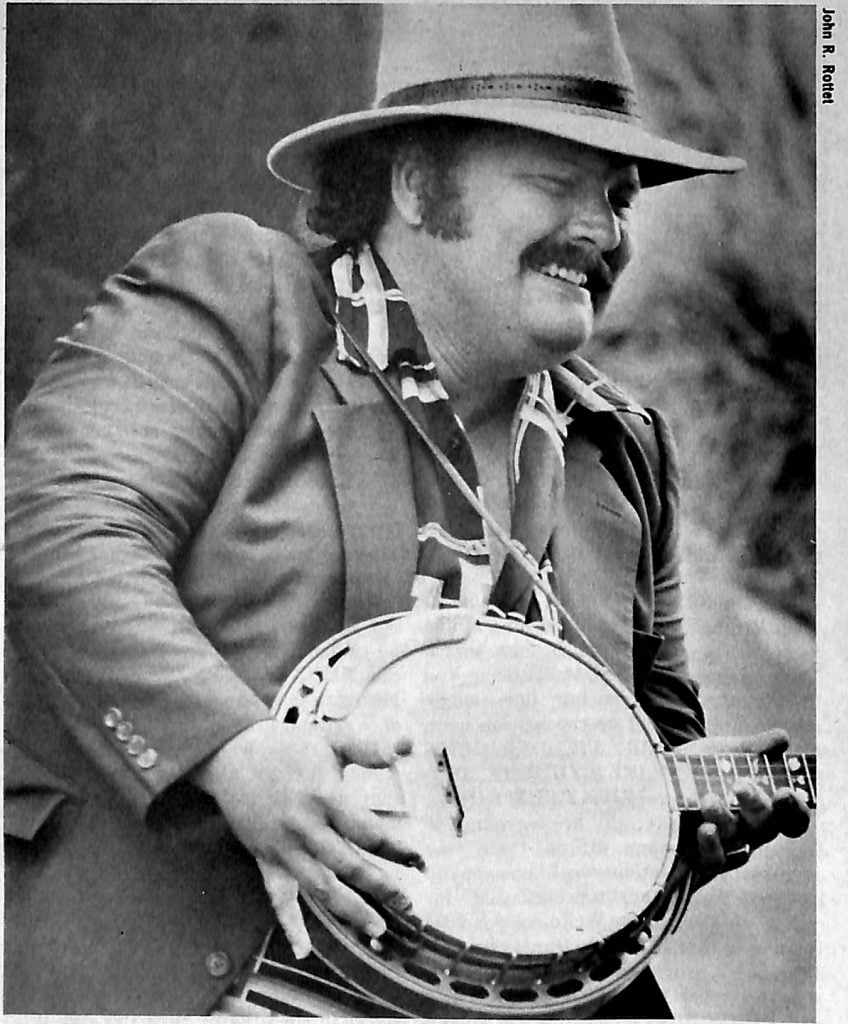

A year went by before I finally encountered the man, in the flesh. He was dominating center stage at the Dahlonega, Georgia Fall Festival, his old Mastertone hanging at his side as he joked easily with the crowd in a soft drawl.

It was hard to believe that this personable bear of a man was the same soulful singer we’d heard. Then he launched into that very song, “99 Years—Tis Almost For Life,” and the audience reaction was like spontaneous combustion. The crowd yelled so loud he had to return to the stage and sing the song again.

As he started into the narrative, the crowd listened carefully to the words of this classic tale:

A sweetheart promises to save her man from going to jail for a crime he didn’t commit, but instead marries the judge while her ex-lover gets sentenced to ninety-nine years.

Dave’s performance, ranging from anguish to rage to despair, takes as many twists and turns as the story line.

After the show, Dave explained how he was able to put so much feeling into that song:

“When you sing something like that, I just imagine that it happened to me. You’ve got to put yourself in that place, that time in history—you’ve got to be right there as though it’s just happening, so that it’s fresh.”

Audiences are not used to hearing such plaintive material delivered so powerfully, and their reaction is immediate and emotional. Well-wishers came backstage not only to say that they’d enjoyed the show, but also to tell Dave personally how much his performance had moved them.

Surprisingly, had it not been for the support of fans like this, Dave might never have embarked on a solo career. Despite ten years’ experience with the likes of Larry Sparks, Red Allen, and the Boys From Indiana, Dave still didn’t feel he had a style unique enough to warrant becoming a headliner.

“People would say, ‘Dave, you really ought to get your own band. You’ve got a certain style, the way you approach a song, the intense feeling you put into it.’ I tried to see these things, but I really don’t stop to look at it. The only time I come close to understanding what they say is when I get into a certain song and I feel it. I realize something comes over me, like ‘99 Years—Tis Almost For Life.’”

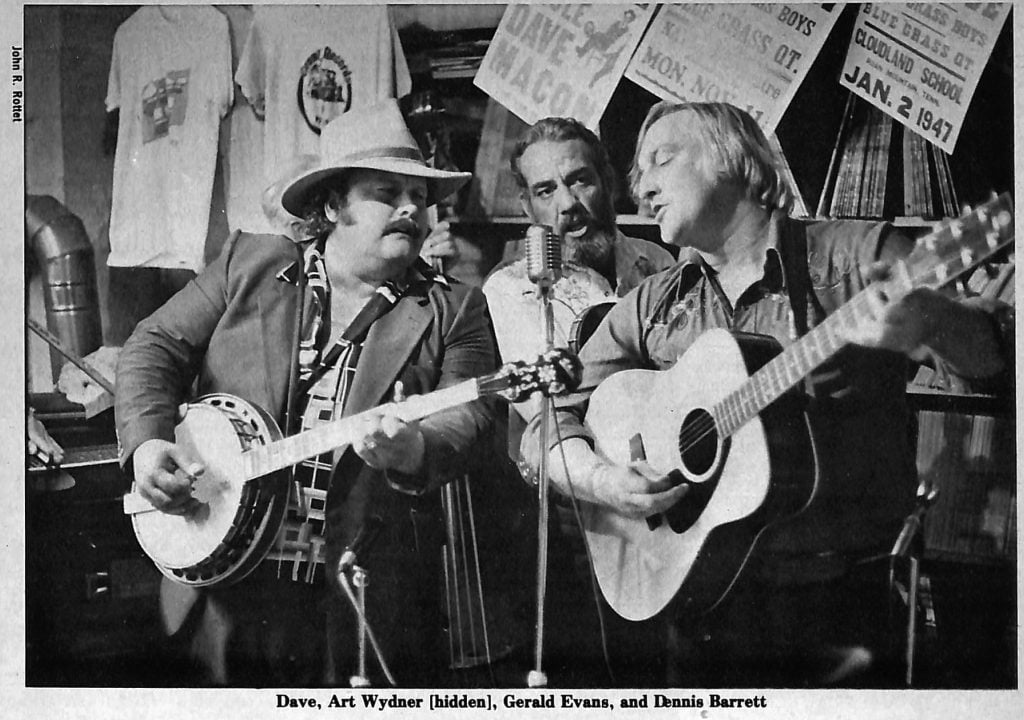

Finally in 1978 Dave formed a group called the River Bend, in which he shared equal billing with three other friends. However, personality differences cut short the group’s life expectancy and left Dave in a leadership role he could no longer avoid.

“I’d gone too far then. I’d made a commitment, starred a group. Too many people walked up and said, ‘Dave, don’t give up the River Bend. You’ve got something different and it’s about time you laid it forth in front of the people.’ I figured if all those folks still had faith in me. I’d give it my best shot. I thank them for that.”

Banjo picking lead singers are rare in bluegrass, but Dave has been singing with the banjo since he was nine years old. He started on an inexpensive instrument that his mother had actually bought for his father for Christmas. His dad showed him some clawhammer licks, and a neighbor started him playing Scruggs style on tunes like “John Hardy,” “John Henry,” “Pretty Polly” and “Little Maggie.” That’s when the singing started to come in handy:

“When I started playing the banjo I had trouble remembering the tunes, so I got to singing the melodies. When I played “John Henry,” I sung it right along. So even if I couldn’t pick it and get the right licks, at least I could sing it. I always relied on my singing to learn the songs right.”

This confidence in his singing has enabled Dave to develop the full range and power of his voice without limiting his creativity on the banjo. The result is a hard-driving combination that has become a striking feature of his live performances.

Dave’s dad learned to pick the banjo during his early years in Bruin, Kentucky in the rural northeastern part of the state. He married a girl from nearby Olive Hill and after World War II moved just across the Ohio line to Portsmouth, where Dave was born July 24, 1950. When the brickyards shut down the Evanses moved further north to Columbus, as did many Appalachians who found the factory jobs there safer and more lucrative than the coal mining jobs back home.

Dave grew up among these people, and bluegrass music was an important part of their social life. It not only brought a touch of home to their new surroundings, but kept the old values and friendships alive as well. Around 1962, Dave began to hear some of the local bluegrass professionals, and a year later met a banjo picker who would become his chief mentor and inspiration—John Hickman.

Now a member of the progressive trio Berline, Crary and Hickman, John was a straight Scruggs picker with the Columbus based Dixie Gentlemen back then. Dave remembers first seeing him on stage:

“We walked in Irv and Nel’s on North High Street and there he was, with another man I was fortunate enough to meet, Pee Wee Lambert. I was thirteen years old at the time and my dad would go with me. Friday nights would come and he’d get off from work and I’d beg him, ‘Dad, let’s go down and see ’em pick.’ ”

Dave started taking lessons from John at a local music store, and his progress accelerated immediately.

“Most folks would have trouble learning a half a song per lesson, I’d go in and learn two songs in a half hour. His picking fascinated me, and I paid so much attention to his every move—especially the drive and the mobility—and with me wanting to pick so bad I really learned fast.”

Playing the banjo became an obsession for Dave, and his parents fixed up a practice space in the garage.

“I practiced continuously. When I’d come home from school at 3:30 they’d find me out in the garage, pickin’. Everbody else was out playing baseball or football—I was the weirdo on the block, I guess. I’d play until the wee hours of the morning, figure from supper time to 2 or 3 A.M., then had to get up for school the next morning.”

Dave’s persistence finally paid off in 1968, when Earl Taylor called from Yakima, Washington to offer him a job picking banjo. The day after his high school graduation. Dave borrowed seventy-eight dollars from his grandfather, bought a one-way ticket West and boarded his first jetliner with dreams of stardom on his mind.

He stayed out in Washington for seventeen months, learning everything Earl could teach him and generally enjoying his first job as a “professional.” One incident from that period stands out clearly in Dave’s mind:

“He give me Earl Scruggs’ pants to wear on the show one time. They were blue serge. I kept them pants, I guess, until they rotted off me. They’d got too little for Scruggs and he give ’em to Earl Taylor, ‘cause they was wearing about the same size at the time. I don’t know if Earl was feeding me a line, ‘course I believed him like everything else that he said. I don’t believe he was kidding me. He said, ‘Dave, them’s Earl Scruggs’ pants,’ in that slow drawl he’s got. I said, ‘They is?’ I went and stood in front of the mirror for an hour, saying ‘I got his britches on!’ I said, ‘Boy, I heard ’em talk about filling his shoes….’ ”

Dave quit the band abruptly in 1969 after receiving word that his mother was seriously ill, and her death shortly there after shocked and confused him. Dave recalls that time in one of his original songs:

So dear to my heart was no one like Mother,

But something was wrong, she wouldn’t say why;

For she left this old world for a brighter tomorrow,

And she left me down here on life’s other side.

If his father had been his heart, his mother had been his soul. Her moral and religious teachings were important to Dave, and provided a sober balance to the social excesses his musical career might have provided. As Dave says: “I knew my God too well to go out and get into trouble, ‘cause I’d have certain penance to pay when I got home.”

Dave stayed around Columbus working at Western Electric and playing with local bands, until Jimmy Martin offered him a job. As they were riding on Jimmy’s bus from Columbus to Ports mouth the first day, Jimmy asked Dave if he was still planning to marry his current girlfriend.

“I’d done told her goodbye, left her crying and all that stuff. He said, ‘Yeah if you marry that girl—you know how he tells the banjo players—you won’t pick the banjo anymore.’ Well, his negative thought about that kinda made mine a positive thought of it. I said, ‘You know, Jimmy, I don’t think she’d do me that way.’ So he dropped me off in Portsmouth, and I quit the same day I got hired.”

Undaunted, Dave returned to Columbus and proposed to his girl, Pattie, that very night. The marriage has lasted happily ever since, and Dave is the first to admit that without the stable home life she’s provided, he could never have withstood the rigors of a professional career. “If you don’t have a woman like that behind you, you’re fighting two battles and you just can’t win.”

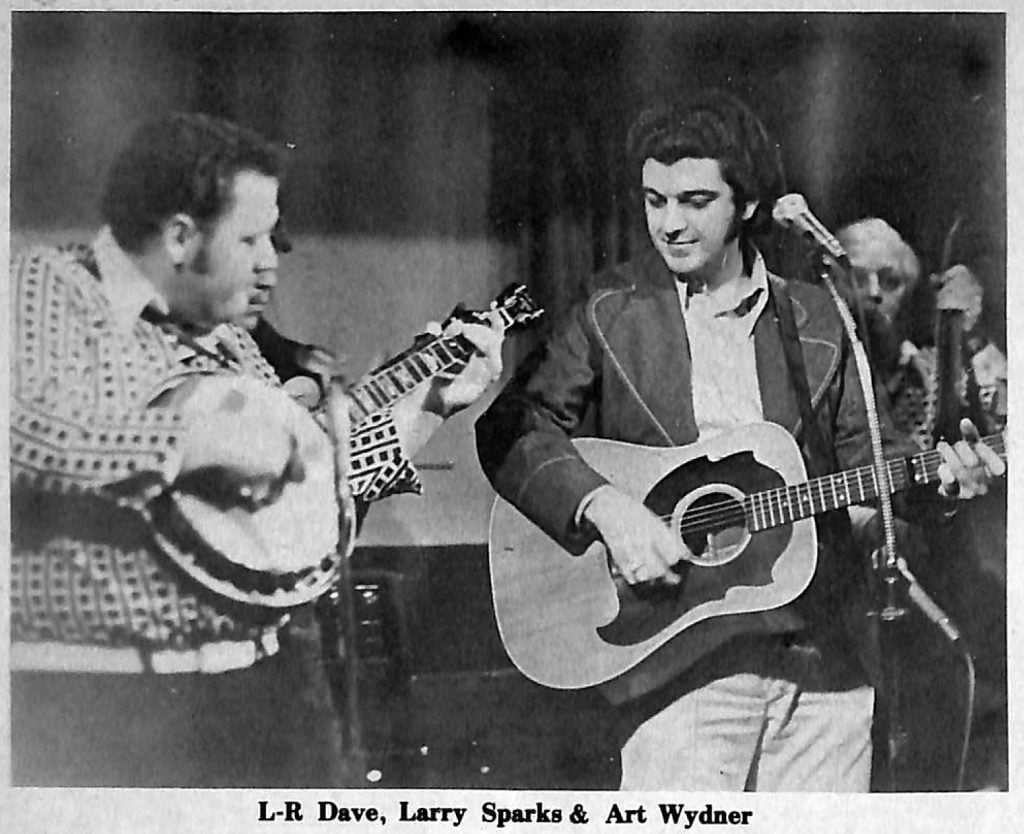

Dave’s next job was with Larry Sparks in 1973-74, a period he enjoyed immensely. He and Larry shared a reverence for the early masters of bluegrass, and a respect for the traditional style. Dave has always regretted not seeing the legendary groups in their early days, when they performed in community churches and halls. But, he notes:

“I was glad when I worked with Sparks, he was booking a lot of little schools and it gave me such a great feeling. We’d walk into some places and Larry would say, ‘Boy, I bet Flatt and Scruggs probably played this very building.’ He’d get me all hyped up and I was ready to go.”

Dave also admired Larry’s intensely personal singing style and the fact that he had played with the master of that genre, Carter Stanley. That style is evident in Dave’s own vocals—the emotional quality that attracts such fervent admirers. In summing up this period, Dave remarks: “There’s nobody I respect any more on the face of this earth than I do Larry Sparks.”

In 1975-76, Dave maintained a rigorous schedule, playing guitar and singing with Lillimae and the Dixie Gospelaires on the road each weekend, and working a full time day job during the week. Eventually it proved too much.

“One day I was driving down the road, hauling a load, had my radio on and they played Larry Sparks’ number “Say Goodbye Little Darling,” and I played the banjo on that. I heard that banjo come on there and that’s all it took. I wheeled the rig around, went back and told the boss toodle-loo. I quit Lillimae too, then the Boys From Indiana called me and I was back on the road.”

The year he spent with the Boys From Indiana was an important step in Dave’s career. For the first time, it showcased his solo vocal talents. Although he strictly played banjo behind the group’s regular numbers, the Boys gave him a solo slot in each set. He started introducing songs like “Ninety Nine Years” and the response was terrific. The Boys encouraged him to front his own group and within a year, following a short stint with Melvin Goins, the River Bend became a reality.

Today, Dave Evans is one of the most compelling performers in bluegrass. He is a man with deep feelings about his music, and an ability to translate them into songs his audience can feel as well. He sings with the sensitivity of Carter Stanley and the power of Ralph, and his original songs show an understanding of many moods. His subjects range from the hell-raising hobo of “Call Me Long Gone:”

They caught me bummin’ in the park one day,

You saw me thumbin’ ‘long the old highway;

Well listen baby, I want you to know, Your dear old daddy’s got a home everywhere I go.

to the soul-searching sinner of “Life’s Other Side:”

There’s no need at all in bottled up feelings,

And the lure of drink is so hard to hide;

I’m down on my knees and Lord, I’m praying.

Won’t you journey with me to life’s other side.

Dave’s religious convictions feed a special need to let his feelings out in his music.

“My mother passed away and her wish was that I’d belong to the church and get saved. It always bears on my mind. Ain’t nobody believes in Him more than I do. But there’s a fear of entering a church house door ’cause I feel that something would come over me and I’d give it all up. And I love my music too much.”

The result is preference for material that stresses the traditional themes of God and family. Dave is a firm believer in the emotional response they evoke.

“If I can relate my feelings to the people and maybe bring a tear to somebody’s eye, make them think about home, mother or something—that does everybody good once in a while. It makes us not forget.”

This is not to suggest that Dave Evans is a one-sided performer. Anyone who has seen him pick a classic banjo breakdown or heard him sing “Whitehouse Blues” can vouch for that. His love for straight ahead bluegrass is obvious in his energetic approach, and he describes his style in terms of the musicians he respects most: “I try and combine the Stanley sound with the smoothness of Flatt and Scruggs and the power of Monroe.”

He acknowledges his debt to those early pioneers with unabashed admiration:

“It’s like looking at a rare looking female, the prettiest you’ve ever seen. You want to talk to her but you say, ‘My goodness, what can I say to this woman?’ And that’s the way it is about this music. What can I say? It’s already been written. It’s already been done and the only thing we can do is maybe add just a little part of it. If I can play the songs somewhere close and get the feeling…”

Thus far, Dave has received encouraging though limited recognition in bluegrass circles. His two albums on the Vetco label have been lionized in the traditional community and almost unheard of elsewhere. He has, however, just recently signed with Rebel so his exposure is headed toward a wider audience. His public appearances have aroused tremendous enthusiasm but have been few and far between. And Dave is discovering that success for a new artist is as much a matter of perseverance as talent.

Bluegrass is not the type of music where one “hit” record can catapult you to overnight fame and fortune. National recognition comes through a gradual accumulation of successful festival appearances, club dates and commercial recordings—a process that can take years.

For Dave this has meant long hours on the road, lots of driving and low wages, while trying to keep a good band together and earning a decent living. The River Bend has undergone several personnel changes, and Dave is still searching for the right combination of musicians to form a stable, long lasting group.

His confidence in his own ability to perform and write propels Dave forward, even as the inertia of getting a new career off the ground holds him back. It is a frustrating situation at best, but finally the pendulum seems to be swinging in his favor. He is starting to come to national attention, and Dave hopes the added exposure will make him more financially attractive to promoters, and musically attractive to the calibre of players he’d like to enlist in the River Bend.

This is an important and precarious period for Dave Evans, and one hopes that his personal conviction and unique vision will carry him through. It is all too seldom that a man of his talents come along. Whether he can achieve national recognition remains to be seen, but it will be interesting to follow his progress along the way.