Home > Articles > The Archives > The Special Consensus—Bluegrass, Chicago Style

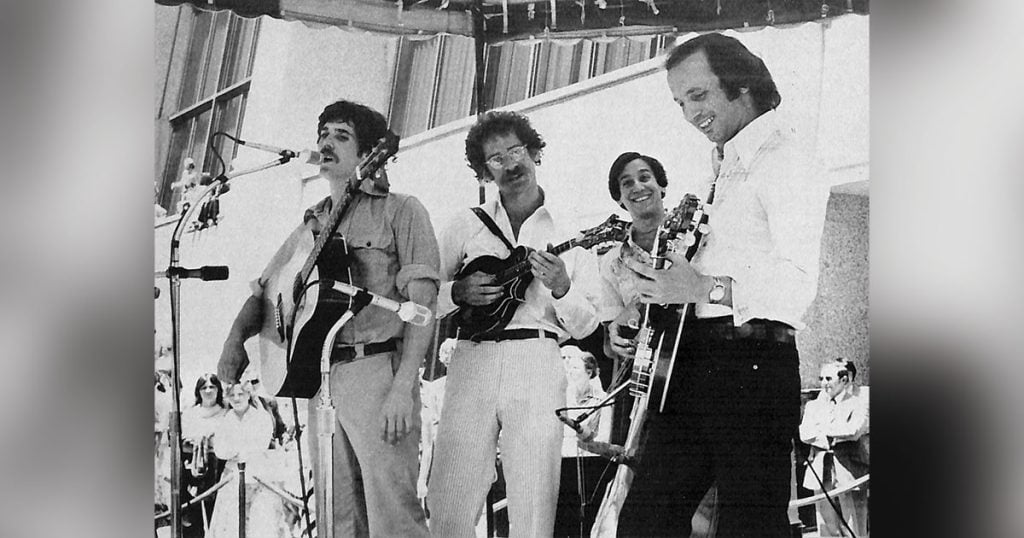

The Special Consensus—Bluegrass, Chicago Style

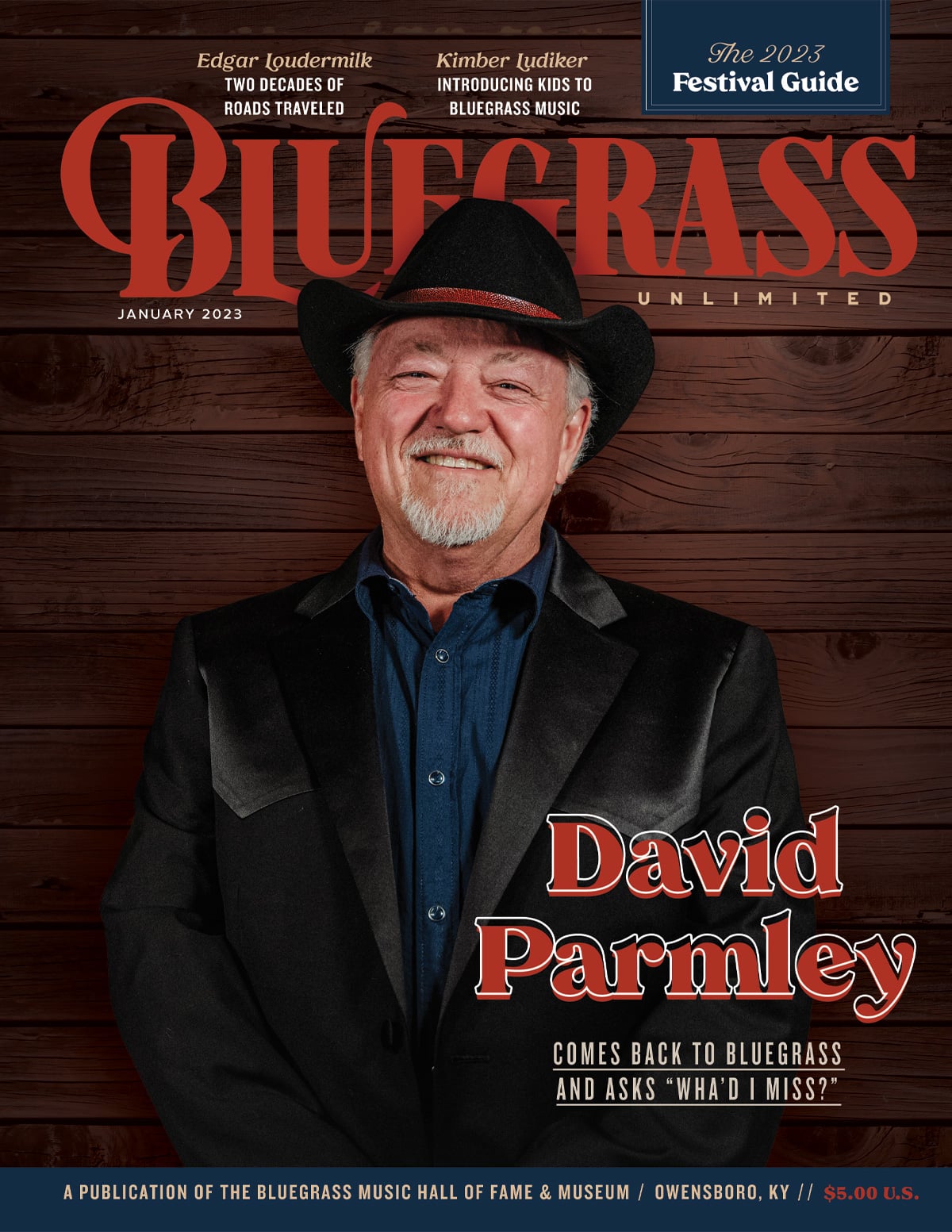

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

February 1979, Volume 13, Number 8

The room is long and dimly lit, the tables packed closely together. Family groups sit elbow-to-elbow facing the stage, which occupies the width of the narrow room. The loud hum of conversation is punctuated by the sound of children’s laughter and the scrape of cutlery against plates. There is a strong aroma of pizza, and a fainter one of beer.

Four figures move about the stage, lifting instruments from cases and unwinding microphone cords. One of them moves forward and taps a microphone.

“Testing, one, two.” A few cat-calls ring out from the back of the room in response, and he grins, waving an arm in that direction. The group clusters together at the rear of the stage, tuning. They separate, and as they move forward their instruments are clearly visible: bass fiddle, guitar, mandolin and banjo.

Could it be bluegrass? In Chicago? Any doubt is quickly dispelled as, after a few introductory words, the Special Consensus Bluegrass Band breaks into a driving rendition of ‘Sledd Ridin’”. The infectious beat immediately has the crowd stamping and hollering its appreciation. The band winds it up with a spectacular riff from the banjo.

The crowd claps and cheers, several people calling requests. The group stands comfortably on stage, enjoying the music and the audience. The set progresses with more bluegrass standards interspersed with a couple of fiddle tunes, a newgrass number, and an original composition. The band looks as though it is trying not to hear the persistent calls for “Foggy Mountain (Breakdown).” There are a few words about their forthcoming album (on Tin Ear Records), and they finish the set with “Black Mountain Rag,” another frequent request. The Special Consensus has recorded this as a single, backed by an original instrumental “Big City Ramble,” and it has been installed in juke boxes in bars at strategic locations around Chicago.

“A small attempt to educate our audiences,” explains Greg Cahill, spokesman for the group.

Before they are through with the last number, one of a party of celebrating salesmen lurches up from a front table and begins bellowing into the microphone. The band gives him space, and eventually one of his colleagues pulls him back into his chair.

They lay their instruments aside and split up, each of them stopping to talk with a different group. Greg describes their attitude towards the audience. “We feel that it’s our responsibility to stop and talk with people. Some of them have been coming to hear us play regularly for more than two years. We like to hear what they have to say, we get feedback from them, and we try to play as many of their requests as possible.”

He is in continual demand. Several of his banjo students are in the audience, and a large group of keen followers who “always wanted to learn banjo, but never had the time.” He casts a few hungry glances at the pizza steaming on the band’s table, but conversation keeps him busy until it’s time for the next set to start. The restaurant manager has a brief word with him as he makes his way back to the stage, and he turns down the sound system slightly. The band members exchange wry looks, and the second set begins.

The first Special Consensus was formed some four years ago. Greg Cahill and Mark Edelsten (bass) were members of the original group. Prior to that time they had been known as The Buffalo Chip String Band, which then became the Cook County Doo-Dah Boys. They had been playing bluegrass, swing, and some country rock, but under heavy pressure from Greg they began to concentrate more on the bluegrass material. Then the name and the instrumentation changed, and the first Special Consensus was created.

The band still plays some material left over from this earlier era, but the swing and occasional newgrass numbers which form part of its repertoire have the band’s stamp upon them; they lean heavily towards a traditional bluegrass sound.

The band played part-time for about a year, and one by one the band members gave up their jobs, and they became the first full-time Chicago bluegrass band. Gradual changes in personnel occurred, and the current line-up developed.

Ed Walsh, guitar, has been with the Special Consensus for about eighteen months. “After graduating from college in Carbondale, Illinois, I joined the band to fill in for a couple of weeks,” he recalls, “and somehow I didn’t get around to moving on.”

Ed was born and raised in Illinois, and his early years were filled with music. Both of his parents played piano, and his grandfather the violin. The children were given piano lessons from an early age, and Ed was a music major for a while in college. He began playing guitar in sixth grade, and experimented with rock- and-roll for a while in high school. His interest in bluegrass began about five years ago, when a friend started to learn banjo. Ed, who was finger-picking at that time, switched to flat-picking with the idea of teaming up with him. This didn’t eventuate, and during his college years Ed played bluegrass duets with another guitarist, and occasional jobs with bands around the Carbondale area.

“I have no desire to play electric guitar,” Ed states firmly. “I play a little mandolin, and at present I am working on learning the fiddle.”

Ed has the best voice in the group, and enjoys the singing. “It really does something for me, although I should practice more on my own,” he admits.

His early influences were Doc Watson and Clarence White, and at present he listens to Tony Rice and Dan Crary. He plays a Mossman guitar, and his mellow and stylish picking is one of the main reasons for the band’s popularity.

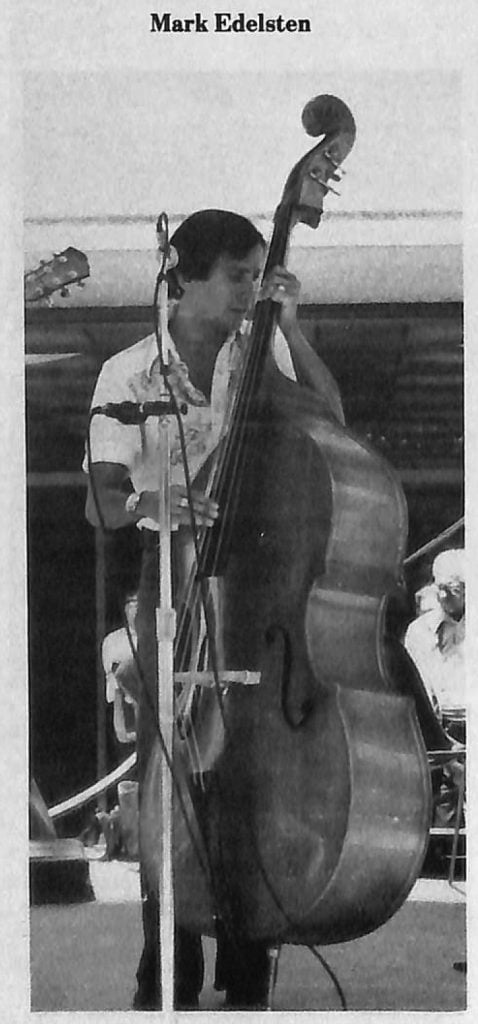

Mark Edelsten provides the solid bass line upon which the band’s exceptional timing relies. His playing is always appropriate, traditional when required, and more inventive when the group plays contemporary material. He feels that his fifth string (a high C) gives him more scope.

Mark was brought up on the south-east side of Chicago, in the steel mill area. He has lived for the past ten years in Hyde Park. Nobody in his family was involved with music, and when Mark at around five years old expressed an interest in playing bassoon, it caused his parents some consternation. After consulting several musicians, they started him on clarinet, feeling that if his interest continued perhaps at some later stage they would be able to afford a bassoon. At about age seven Mark began taking clarinet lessons, and played for several years.

When he entered high school his ambition was realized, and for the next few years he played both bassoon and clarinet. During this time he bought a bass guitar, and played rock with a group. While at the University of Chicago he began playing harmonica, sitting in with many well-known Chicago blues bands, including Hound Dog Taylor.

On graduating from college he resolved to join the first band which asked him, and The Buffalo Chip String Band introduced him to bluegrass. When the band’s orientation shifted more towards bluegrass, he switched to string bass. His listening embraces jazz, classicial, blues, and bluegrass.

His playing has been influenced by bassists such as Joseph Guastefeste (Chicago Symphony), Charlie Mingus and Ron Carter. Jack Cooke and Roger Bush are two of the bluegrass musicians to whom he listens. Mark’s voice has a wide range, and usually sings the tenor part.

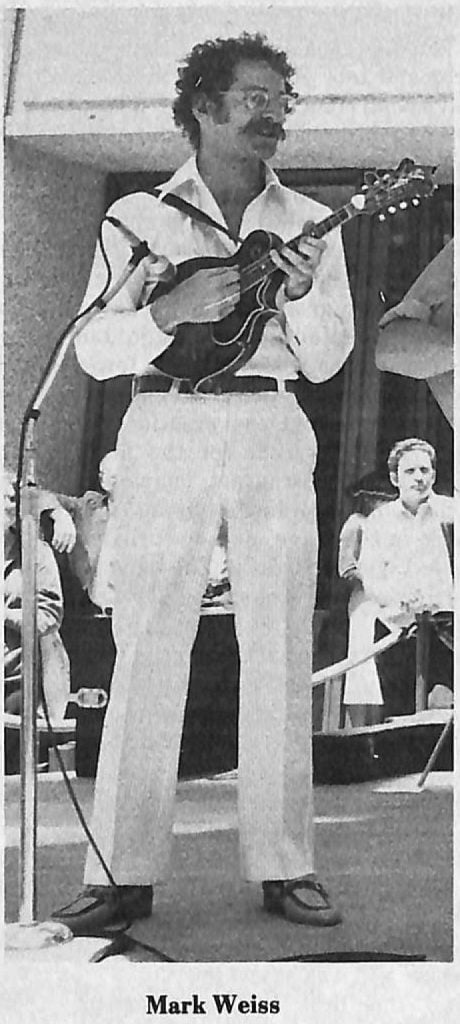

Mark Weiss (mandolin), is originally from Long Island, N.Y. While in high school he heard the Dillards, and was immediately interested. He did his undergraduate work at the University of Wisconsin, in Madison. It was not until he was in graduate school that he became active in bluegrass, and began to play the mandolin. He first played old- time music as much as bluegrass, and has always been interested in jazz dating from the twenties through the early sixties.

Although none of his family played an instrument, his mother sang, and he recalls the music of his youth to have been “show tunes, mostly Broadway stuff.” He taught elementary school for a year after graduate school, and first joined the Special Consensus in 1976. He stayed with them for about four months, and then moved on to play as a solo act in local restaurants. At that time his primary interest was in composing and performing his own material, and his compositions were heavily influenced by early twenties jazz. His listening encompasses a wide range of styles, from John Coltrane to Rick Skaggs and Frank Wakefield. He feels his chief bluegrass influence has been the playing of Bill Monroe. Mark took a few lessons from Jethro Burns, but is mainly self-taught.

“I tend to be influenced most by the people with whom I am currently playing, in this case Greg and Ed. I don’t listen to many mandolin players now, and what I come up with is usually fairly spontaneous.”

When his schedule with the Special Consensus allows it, he plays Appalachian square dance music with the Chicago Barn Dance Company. “I am not exclusively bluegrass oriented, and I’d like to have more time for my own compositions, but by playing with both bands I get enough variety to satisfy me.”

His playing is tasteful and imaginative, and reflects his strong interest in jazz.

Greg Cahill’s musical education started as a child, when he began to play accordion. He played for eight years, absorbing the theory which has stood him in good stead as a banjo player. “I was brought up on the south side of Chicago. My sister and I played local concerts as an accordion duo, but I could never really feel the music,” he relates. “It wasn’t until the Kingston Trio became popular that I began to hear music which I could really enjoy.”

During several years of college, and a couple of years in the army, Greg played about with the banjo and guitar, and his interest in bluegrass was first aroused when he was stationed in Georgia.

After graduate school he played guitar for a while, and worked as a counselor in an adolescent drug program. It was during this time he heard the Greater Chicago Bluegrass Band, formerly the only bluegrass band working regularly in the Chicago area.

“I listened to Richard Hood, and suddenly I realized that this sort of banjo music I could really feel!” He took a few lessons from Richard, who introduced him to the music of J. D. Crowe, and his interest grew rapidly. By this time he was married with one child, working full-time, and playing banjo six to eight hours a day.

“It was getting completely out of hand. I’d come home from work and play my banjo until three or four in the morning. Often I fell asleep holding it, and woke up in the chair next morning in time to go back to work.”

Fortunately Greg’s wife was very understanding, and they agreed that after a few months of concentrated saving, Greg would give up work for a year, and learn to play the banjo. Shortly after this time the first Special Consensus was formed.

Greg has gone through many changes during the development of his personal style. He went through a melodic period, picking Courtney Johnson breaks note for note. He began to lose that basic feeling which had attracted him to the banjo initially, and experimented with adapting jazz saxophone licks on the banjo.

“Somehow this brought me full circle, back to the J. D. Crowe and Scruggs stuff which had first made sense to me.” Greg describes himself as predominantly a Scruggs stylist, although he makes discreet use of melodic licks in many of his breaks. His back-up playing is discreet and stylish, and he spends almost as much time on this aspect of his playing as he does on his lead breaks.

He feels that the J. D. Crowe philosophy of solid timing is the basis of good banjo playing. “That, and playing out of chord positions, are the two most important aspects.” He plays an old Mastertone with a new neck, and has recently bought a Stelling which he is starting to use almost as often.

“I try to make my playing as tasteful as possible,” he explains. “I’d hate to be ‘The Guy With The Mastertone,’ who steamrollers over everyone else’s breaks.” Greg teaches banjo in Chicago, and with other staff members of The Old Town School of Folk Music was recently part of a folk music program on local T.V.

The cutting precision and driving solidity of his breaks, and the careful attention he pays to back-up, assure him of more banjo students than he can handle.

“I never get enough time to practice,” he says, regretfully. “I’d like to play three or four hours a day, but I can’t always manage it. Gerry, my wife, has had to take up mandolin in self-defense!” The Special Consensus has played as a warm-up act for many of the top-line bluegrass bands which have visited Chicago. At least once a week when in town they use a fiddle player, Bob Hoban (of Flying Fish Records). Bob is also a pianist, and has played with Joe Venuti and Jethro Burns. Jethro has sat in with the Special Consensus on a few occasions.

Greg, who usually sings baritone, explains their method for working up new material. “We don’t have any really great voices, but between us we can cover the parts required for bluegrass harmony. Most of our rehearsal time is spent on the vocals, and we sing a lot in the car when we’re travelling between jobs. The instrumentals are worked on individually. We agree on some idea of an arrangement, and each of us works on our breaks and back-up for a while. Then we put it together and polish it up for a day or so, and it’s ready.”

The Special Consensus is in steady demand, and the band members share a common ambition to make the band as good as it can possibly be. “Fortunately, we’re all fanatics!”

A series of unsatisfactory agents held them back for a while, but their current management is providing them with enough work to keep them extremely busy. Much of their work is in local clubs, which vary from family-style restaurants to bars in less attractive neighborhoods.

Greg laughs a little weakly as he describes their first night in one of the bars they play regularly. “We had just finished an up-tempo number, and the crowd was clapping and shouting, and we started the intro to ‘Footsteps in the Snow.’ Suddenly a couple of shots rang out in the street, right outside the window. Everyone in the bar who was sober enough to stand immediately hit the floor!”

The band enjoys the college circuit, especially a concert environment. “It makes us take more care in presentation, and encourages us to be more professional.”

They play colleges and other jobs in Michigan, Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana and Kansas. Park district concerts are popular with the band. They play an occasional festival, but have yet to solve the economics of festival jobs.

“We’d love to play more festivals, the audiences are usually more knowledgeable about bluegrass. For a full-time band, though, it’s a difficult situation. Top-liners like the New Grass (Revival) or Bill Monroe are the main attractions, and the smaller band is in an awkward position. It’s much worse for us, because we’re so far away. We can no longer afford to drive several hundred miles to pick in the parking lot in the hope that someone will like us, or even to play a few tunes on the stage. Often we have not been paid a set fee, and have had to take a percentage of the profits. This often doesn’t even cover our travelling expenses and food. We’ve tried sending tapes around to promoters in the hope they will feature us and give us a fair deal, but I don’t blame them for not wanting to take on a band they don’t know. In Chicago we’re a long way from the regular circuit, and promoters in Georgia and Virginia probably wonder what Yankees are doing playing bluegrass, anyway!”

Local interest in bluegrass has been growing steadily, particularly in the last two or three years. Mark Weiss sums up the feeling of many Chicago musicians.

“Greg has been the main reason for the development of bluegrass in this area. Not only does he set a brilliant example with his playing, but for the past four years he has worked constantly to have bluegrass introduced into clubs in Chicago.”

Mark Edelsten feels that the surge of interest in bluegrass would be stimulated further if promoters would organize a few festivals close to Chicago.

“A lot of people who don’t go to clubs would go to a festival, and there’s nothing like hearing a good band in person. Records are fine, but it’s that indefinable essence of bluegrass which comes over so much better in live performance which we need.”

Greg is happy about the growth of interest in bluegrass. “I used to constantly worry about the bookings for the month-after- next,” he laughs. “Now I don’t worry any more, and the bookings take care of themselves.”