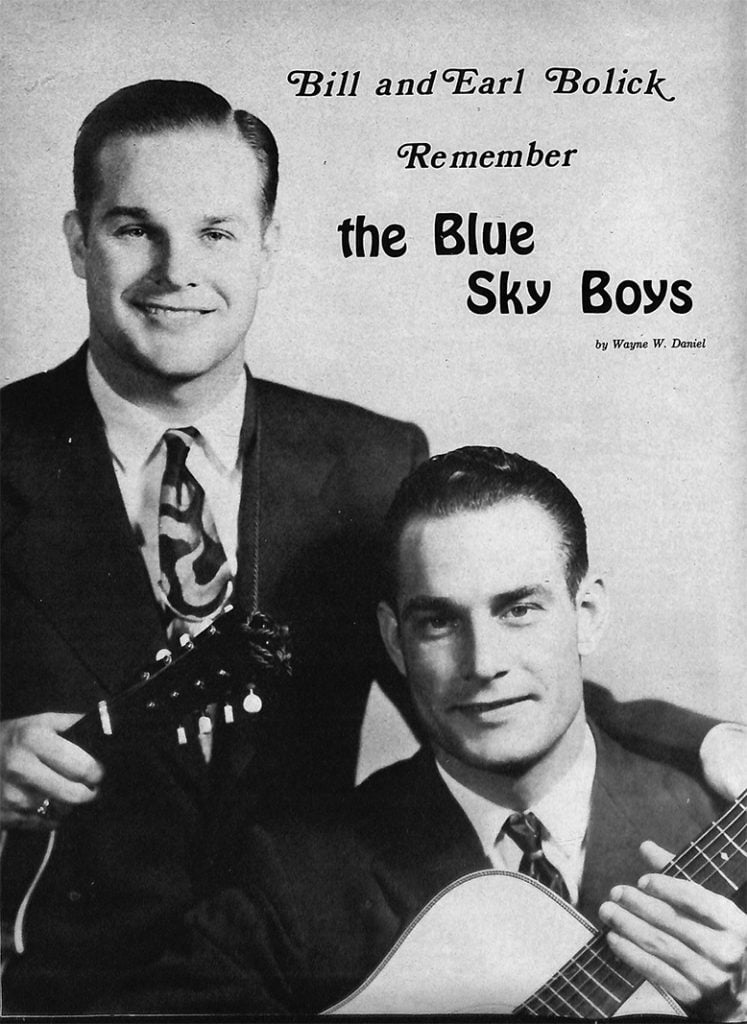

Home > Articles > The Archives > Bill and Earl Bolick Remember the Blue Sky Boys

Bill and Earl Bolick Remember the Blue Sky Boys

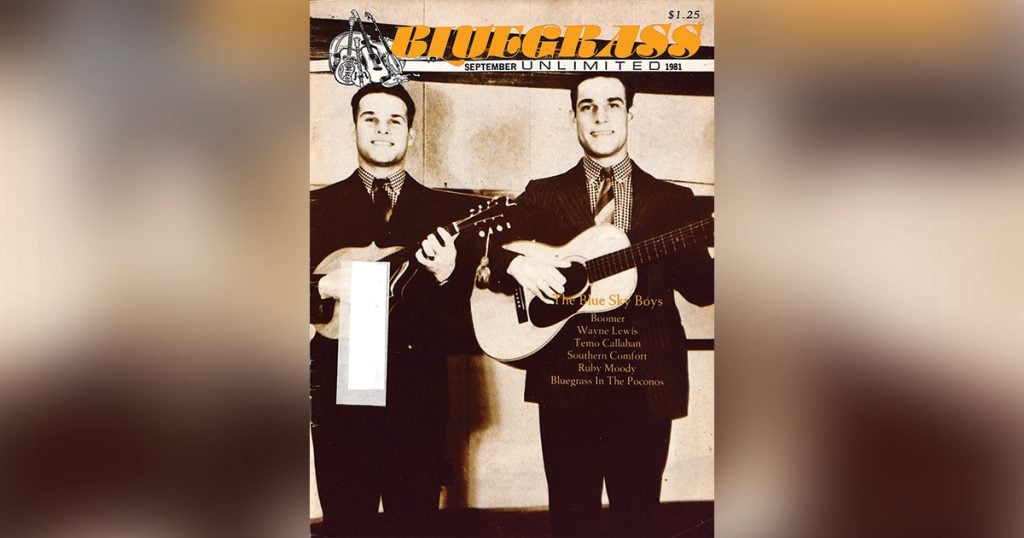

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

September 1981, Volume 16, Number 3

Of the many mandolin-guitar groups of the thirties, none was of greater importance, in terms of tradition, than Bill and Earl Bolick, popularly known as ‘The Blue Sky Boys.’” So writes Bill C. Malone in his book, “Country Music U.S.A., A Fifty Year History.”

Evidence of the importance of the Blue Sky Boys to present-day bluegrass music is readily available. Bill Foster [BU-May 1980], leader of what has been described as “one of the most popular bands on the southern festival and concert circuit,” states that in the early days of his musical career he and his brother Jim developed a style in which they tried “to sound just like the Blue Sky Boys.”

The Bolick brothers’ influence on today’s bluegrass music is a matter, not only of style, but of repertoire as well. At any bluegrass festival, chances are that the audience will hear at least two or three songs that were recorded and popularized years ago by the Blue Sky Boys. A Lewis Family [BU-June 1980] set, for example, is likely to feature such songs as “The Sunny Side of Life” (recorded in 1936 at the Blue Sky Boys’ first recording session) and “The Sweetest Gift, A Mother’s Smile” (a post-war release by the Bolicks).

But when you talk to the Blue Sky Boys about their music, there is one point that they immediately endeavor to make clear—their sound “was not bluegrass.” “Although we played a number of songs rather fast,” Bill explains, “I don’t feel we ever had a bluegrass sound. I associate bluegrass strictly with the Monroe high-pitched type singing and fast, hard-driving instrumentals, featuring the Monroe style mandolin and stereotyped by the Scruggs banjo. If music isn’t of this type, I don’t consider it bluegrass. Definitely, we never had this type sound. Most of our songs were sung at a moderate pace in a key that fitted our natural voices. We were definitely softer.”

In his book, Malone goes on to state that the Blue Sky Boys’ “personal popularity, gained largely through radio and personal appearances, was exceeded by no other duet—not even the Monroe Brothers—in the southeastern states during the late thirties.”

The radio and personal appearance career of the Blue Sky Boys had its beginnings back in 1935 at WWNC, Asheville, North Carolina, when Bill, born October 29,1917, was seventeen years old and Earl, born November 16, 1919, was fifteen. In the fall of 1935 Bill, Earl, and fiddle player, Homer Sherrill, appeared on the station as the Good Coffee Boys sponsored by JFG Coffee. To the radio audience they were John, Frank, and George—names suggested by the JFG in their sponsor’s name.

At first Earl played guitar accompaniment to their singing, and Bill alternated between the guitar and mandolin. “We both felt our singing sounded better with the guitar-mandolin combination than with two guitars,” Bill relates, and apparently their listeners shared this opinion. “People kept requesting that I play the mandolin more,” Bill continues. Eventually he switched completely to the mandolin as his instrument on all their numbers.

Earlier in 1935 Bill had appeared on WWNC with the Crazy Hickory Nuts, a Crazy Water Crystals sponsored group consisting of Homer Sherrill (fiddle); Homer’s brother Arthur Sherrill (mandolin); and Lute Isenhour, a five-string banjo player.

Subsequent pre-war radio concomitant personal appearance engagements took the Bolicks to WGST in Atlanta, Georgia on three different occasions (March-June, 1936; February-July 1937; January, 1938-December, 1939); WSOC in Charlotte, North Carolina, and a two or three week stint with J.E. Mainer (August, 1936); to WPTF in Raleigh, North Carolina (December, 1939-April, 1941); and to WFBC, Greenville, South Carolina (May-August, 1941).

The Bolick brothers’ first appearance on Atlanta’s WGST in March of 1936 followed directly on the heels of Bill and Charlie Monroe who had been at the station for about a week. The Monroe Brothers played their last WGST radio show at 12:15p.m. on March 3, and the Bolicks made their initial appearance at 7 a.m. on March 4. During this first Atlanta stint Bill and Earl were known as the Blue Ridge Hillbillies, a name given them by J.W. Fincher, manager of the Georgia-Carolinas division of Crazy Water Crystals, the Hillbillies’ sponsor at WGST.

After a three month’s stay in Atlanta, Bill and Earl, on June 16,1936, entered an RCA Victor recording studio in Charlotte, North Carolina, to make their first phonograph records. The session director, Eli Oberstein, was surprised to see the Bolick brothers when they made their appearance at the studio. As Bill recalls, “When we quit in Atlanta (shortly before the recording session), Mr. J.W. Fincher or members of his company (the Crazy Water Crystals Company) informed RCA that Earl and I weren’t working together anymore, and wouldn’t be fulfilling our recording agreement. Earl and I thought our agreement was still in effect as we hadn’t been notified differently. Homer Sherrill and two fellows, Shorty and Mack, who replaced us in Atlanta, recorded in our stead as the Blue Ridge Hillbillies, the name we had used in Atlanta. Thinking we had cancelled our engagement, and thinking we were only curious onlookers, Eli became a bit upset when he noticed our presence.”

Once the misunderstanding was cleared up, however, Bill and Earl were allowed to record, and ten sides from the session were released on the Bluebird label: “I’m Just Her to Get My Baby Out of Jail,” “Sunny Side of Life,” “There’ll Come a Time,” “Where the Soul Never Dies,” “Midnight on the Stormy Sea,” “Take Up Thy Cross,” “Row Us Over the Tide,” “Down on the Banks of Ohio,” “I’m Troubled, I’m Troubled,” and “The Dying Boy’s Prayer.”

When the question arose regarding a name to put on the Bolick brothers’ records, Oberstein expressed the opinion that it would be better to adopt some name other than the logical “Bolick Brothers,” since so many brother acts were already recording. “We kicked the idea around a bit,” Bill says, “and came up with the Blue Sky Boys, a name taken from the Blue Ridge Mountains and higher elevations near Hickory, North Carolina, area commonly referred to as the ‘Land of the Sky.’ So as not to lose our identity, our recordings came out with our names, Bill and Earl Bolick, listed in parentheses, beneath The Blue Sky Boys.”

Between their first recording session and their entrance into military service, the Blue Sky Boys, at seven different Victor sessions, recorded eighty additional sides, all but three of which were subsequently issued. Of those not issued, one was because of a lost master, and another could not be issued because the master was broken.

The Blue Sky Boys had been at WFBC, Greenville, South Carolina, only a sell pictures, books or anything along that line on our radio programs. “Not long after that, Jim called me where I was rooming and asked me if I could come to the station and talk with him. When I arrived he told me we would be given a substantial raise beginning next week. His offer was, by far, the largest amount we had ever been paid. I know of no outfit that had been offered that high a salary prior to World War II—not in the south. Most worked as we did, on a sustaining basis. Sadly, I reached in my pocket and handed him a notice from the draft board telling me to report for duty on August 11, 1941. In no more than two weeks we were in the armed forces and didn’t return to entertaining for over four and a half years.”

Eighteen months of Bill’s military duty was served in the Pacific theater where he participated in the initial landings on Leyte Island in the Philippines and Okinawa. Earl, who was a medical paratrooper with the 82nd Airborne Division, won several medals and decorations, including the Purple Heart with Oak Leaf Cluster and the Silver Star.

After World War II (Earl was discharged in September and Bill on Christmas Day of 1945), the Blue Sky Boys resumed their singing career in March, 1946, at WGST in Atlanta where they stayed until February of 1948. For six or eight months their Atlanta programs were heard also via transcriptions on radio stations in Macon and Savannah, Georgia. The Atlanta tour was followed by engagements on WNAO, Raleigh, North Carolina (March, 1948-March, 1949); WCYB, Bristol, Virginia (March-December, 1949); WROM, Rome, Georgia (December, 1949-April, 1950); KWKH, Shreveport, Louisiana, (April-August, 1950); and a second tour of duty at Raleigh’s WNAO (August, 1950-February, 1951).

Before disbanding in February of 1951, the Blue Sky Boys, after the war, recorded some thirty-six sides for RCA Victor at recording sessions in Atlanta (September, 1946, January, 1949), New York City (May and December, 1947), and Nashville (March, 1950). From this period of their career came the Blue Sky Boys’ biggest hit, “Kentucky,” a song composed by Karl Davis and Harty Taylor. “As nearly as I can estimate,” Bill states, “we sold approximately a half million copies of that record.”

Country music historian, Douglas B. Green, has stated that “The Blue Sky Boys were famous for their religious songs and sentimental tunes of the 1890s and earlier, as well as for their well known versions of American and British folk songs.” Commenting on the Blue Sky Boys’ repertoire, Bill says it consisted of “a good fifty per cent religious type songs. The rest of our programs were split between traditional and contemporary folk music.”

The Blue Sky Boys learned their material from a variety of sources. “I learned the tunes of a few songs from my maternal grandmother,” Bill notes. “When she would visit with us I continually aggravated her to sing me some of the old songs she knew. I remember her singing songs such as ‘Sing a Song, Kitty’ and ‘Cindy.’ I cannot recall, however, learning the complete words to any song from her.

“My mother was much the same way,” Bill continues. “She was the first person I can ever recall hearing sing ‘Bonnie Blue Eyes,’ but she only knew a verse or two.”

According to Earl, his and Bill’s father frequently sang around the house. “Especially on Sunday mornings we’d wake up hearing him singing hymns,” Earl recalls. “We definitely learned a lot of our hymns from him,” Bill adds. “I can directly associate him with songs like ‘When the Ransomed Get Home,’ ‘The Hills of Home,’ ‘Only Let Me Walk With Thee,’ ‘No Disappointment in Heaven,’ ‘An Old Account Was Settled,’ and many, many more.”

The song, “Are You From Dixie,” so closely identified with the Blue Sky Boys, and adopted as their theme song in 1938, was learned from Lloyd Price, a singer who lived near Bill and Earl while they were growing up and with whom they did some occasional singing.

Bill also points out that a lot of the Blue Sky Boys’ songs were learned from Lute Isenhour, the five-string banjo player with the Crazy Hickory Nuts. In addition, Bill says, “our radio audience sent us a lot of songs, and publishers continuously sent us hundreds, even thousands, of published songs. I learned to read music to a certain degree, and in this manner learned a lot of songs.”

“Sometimes we would rewrite old songs, making up a little here and there, and maybe adding a verse when we knew only part of a song,” Earl explains. “Many of the old-timers sang a song exactly as it sounded to them,” Bill elaborates. “There were many times a lot of the words just didn’t make sense. When this happened I always tried to rewrite it enough to make it understandable.”

Ed Davis in a 1974 article in the Greensboro (North Carolina) Daily News, writes that “Bill and Earl Bolick developed a style of close harmony singing that is at the very foundation of a great deal of what is called country music today, and they perfected it to the point that their music served to define the style.”

Bill Bolick explains how he and Earl developed their style. “Both of us realized from the very beginning that in order to produce good, clear harmony, one had to sing at a moderate pace in order to be understood, and softly if your voices were to blend. From the first, we strove to keep the harmony and lead separate. Many of the early duets did what we termed ‘ran together.’ In other words, they sang identical notes instead of lead and harmony. This is one thing we were very careful about. If you will listen to any song we ever recorded, I don’t think you will find one where we sang portions of a song without clearly separating the lead and harmony.

“We always tried to sing in our natural God-given voices. We never attempted to copy anyone’s style, or sound like them. We didn’t try to see how high we could sing, or how loud we could sing. We tried to sing in a key that we felt would suit our voices best, without yelling or straining. We didn’t play our instruments loud. When it was necessary that the harmony reach a high pitch, I learned to reach these notes without increasing the volume of my voice so the sound that I attained wouldn’t be any louder than Earl’s lower-pitched voice. We must have been pretty successful at this, because over practically all the radio stations we ever worked, the control men would tell us that we were easier to ‘ride gain’ with than anyone they had ever worked with, regardless of who it was. This simply meant that they seldom had to touch the controls to bring us up or down. Our voices and music usually stayed within an acceptable level.”

All of the Blue Sky Boys’ pre-war recordings were vocal duets by Bill and Earl accompanying themselves on guitar and mandolin. When asked to describe his mandolin style, Bill replies that it is “altogether different from the bluegrass” style. “From the very first I never simply chorded while we sang. Over the years I worked constantly to develop a sound that would be similar to a third voice of fiddle background while I was singing harmony with Earl. I felt it was a very difficult style. Even the few duets that have been influenced by us have never tried to duplicate my style while singing. I didn’t always accomplish, on every song, what I really wanted to do, but had we continued playing, I think I could have. If you will listen to the mandolin on our Victor recordings of ‘Kentucky,’ ‘I’m Glad,’ ‘Sold Down the River,’ ‘Behind These Prison Walls of Love,’ ‘The Unfinished Rug,’ and ‘Where Our Darling Sleeps Tonight,’ I think you will get a pretty good idea of what I was trying to do, how difficult it was to do, and the distinct difference from the bluegrass style. We always felt the singing was more important that the instrumentals, and for that reason didn’t try to make the instrumental work outstanding. We tried to develop a style of playing that would enhance our voices.”

At the Blue Sky Boys’ first two recording sessions Bill played a homemade mandolin he had bought in an Atlanta pawn shop. “I think I paid eighteen dollars for it,” Bill reminisces. “I understand it was made by a fellow named Hembree. It was made of oak with F holes and curved top. It sounded so much better than the mandolin I was playing, which was a cheap one, I simply thought the tone was beautiful. The mandolin I had been playing was a production-line job that could have been equaled anywhere for six to ten dollars.”

The mandolin heard on Bill’s later recordings is a Martin, Model 20, made in 1929. Bill purchased the instrument new in 1937, for seventy-five dollars, from the Cable Piano Company, a then popular Atlanta music store. “I understand that less than three hundred of this model were ever produced,” Bill notes. The instrument’s sides and back (which is curved) are made of curly maple and the arched top is spruce. The pick guard, fret board, and bridge are all made of genuine ebony.

On all Blue Sky Boys radio programs, personal appearances, and recordings prior to 1940, as well as on the records made at their first 1940 session (February 5, 1940), Earl played an 0-28 herringbone Martin guitar that belonged to Bill. Made in 1929, the guitar was purchased by Bill in 1935 for seventy-five dollars. In 1940 Earl purchased a D-28 herringbone Martin which he still owns. Through his father’s connections he was able to obtain the instrument at a wholesale price of ninety dollars.

Throughout their career Bill and Earl Bolick performed with a third person in their act. During the Good Coffee Boys days and the first two jobs at WGST in Atlanta, the third musician was Homer Sherrill, a fiddle player, who served as emcee at personal appearances. According to Bill, he, Homer, and Earl sang very little, if any, together. When Sherrill left the Blue Sky Boys in 1937 he joined the Morris Brothers [BU-Aug. 1980].

Richard “Red” Hicks, like the Bolicks, a native of North Carolina, joined the Blue Sky Boys in 1938 and performed with them until October of 1940. “When Red joined us,” Bill relates, “we immediately started working on the trios and usually included at least one on each program.” Hicks sang lead to Earl’s bass and Bill’s tenor. Many, perhaps half, of the hymns heard on Blue Sky Boys programs during this period were done by the trio. Hicks, who played guitar and mandolin, sometimes played mandolin duets with Bill and sang two or three solos each week on the radio programs. As Bill recalls, Hicks usually sang western and semi-pop songs like “Home in Wyoming,” “Riding Down the Canyon,” “Silvery Moon,” “Gold Mine in the Sky,” and “Red Sails in the Sunset.” He was particularly fond of the western songs that were in vogue at the time.

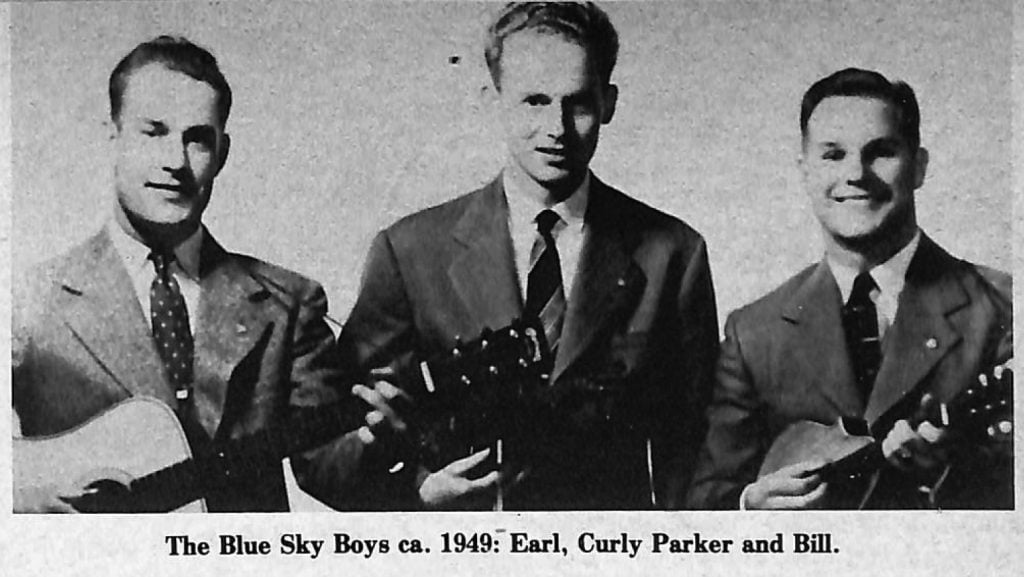

When Hicks left the Blue Sky Boys he was replaced by a native of Gilmer County, Georgia, Samuel “Curley” Parker, who was a part of the act until they were separated by the war. He rejoined Bill and Earl after the war and remained with them until June of 1949, except for a brief period from the fall of 1947 until January of 1948 when he was replaced by Joe Tyson whose home was in the Carrollton/Villa Rica, Georgia, area. According to Bill, Curley, whose previous experience had included that of fiddle player with the Holden Brothers, had not done much singing before joining the Blue Sky Boys. “But in several months,” Bill adds, “we had him singing a pretty good lead. All in all, I believe his voice blended with ours better than anyone else that ever sang with us. We received as many requests for some of our trios as we did for our duets.”

Parker, who was the first musician besides Bill and Earl to record as a member of the Blue Sky Boys, joined the Bolicks for their 1946 and 1949 sessions in Atlanta and the May 1947 session in New York City. These sessions produced, in addition to “Kentucky,” such other Blue Sky Boys favorites as “Dust on the Bible,” “Sold Down the River,” and “The Sweetest Gift, A Mother’s Smile.”

The last musician to perform with the Blue Sky Boys before their break-up in 1951 was fiddler and bull whip artist, Leslie Keith, who replaced Curley Parker. Joining the Bolicks in June of 1949 while they were working at WCYB in Bristol, Virginia, Keith had previously worked for another entertainer named Curly King. “When we hired him, we didn’t even know he did a bull-whip act,” Bill explains. “We learned later he had presented it with the Stanley Brothers and Curly King’s group. The main thing that surprised me about Leslie was his ability to do things without practice. He was also an excellent banjo player, using the old-time clawhammer style. Here again, he seldom practiced. He didn’t have a five-string banjo of his own. When he played it, he used mine. He told me he could play the harmonica similar to Wayne Raney, but didn’t own one. I bought him several cheap ones, and surprisingly, he could do selections like “The Fox Chase” and “Pan-American Blues” very well. I always felt his background playing was a bit rough for our type of music, but he was certainly gifted in many ways.”

Keith joined the Blue Sky Boys at their last pre-1951 re-recording session which was held in Nashville. Songs recorded at this session included “There’ll Be No Broken Hearts for Me” and “Where Our Darling Sleeps Tonight,” both of which were written by Bill and Earl; Karl Davis’ “The Unfinished Rug”; and a re-recording of Bill’s arrangement of “Sunny Side of Life.”

In 1946 William A. Farr attended a Blue Sky Boys concert at Tyrone School near Atlanta. In an article in Sing Out! magazine he recalls that “Unlike others who had come from radioland sporting cowboy hats, stomping and yelling, they stepped quietly onto the stage dressed in business suits. Instead of mouthing ungrammatical greetings…, Bill thanked us for the applause but requested that we listen to their songs.”

“Our stage shows lasted approximately an hour and a half,” Earl explains. “We would sing for thirty-five or forty minutes, then we’d have our comedy routine, do a fast number, and close with our theme song.” While Earl was dressing for the comedy part of the show, Bill would usually sing a solo (frequently of a comic nature), tell a joke or two, and do a selection or so with the other member of the group. It was also at this time that the third member of the group usually did his specialty.

Beginning in 1938, the Blue Sky Boys’ comedy routine centered around a character called Uncle Josh, who, according to Earl, who played the part, “was an old man who thought he knew everything, but didn’t know anything.” Before Uncle Josh came on the scene the comedy act had consisted of Earl playing blackface and Bill playing either blackface or a rube character. In creating Uncle Josh, Bill explains, “we were striving for something different, as most acts in those days either worked blackface or rube comedian or both.”

Those who saw Uncle Josh on stage remember his baggy trousers, more or less held up by a giant safety pin and untrustworthy looking suspenders; his floppy felt hat; and his oversized shoes. Wire-rimmed spectacles perched low on his nose, a corn cob pipe, and a rummage-sale coat and tie completed his costume. While Leslie Keith was with the Blue Sky Boys he combined his whip act with the Uncle Josh routine in a performance which, Bill says, “never failed to bring the house down.”

Unlike so many of the early country music radio shows, whose exact content and format have long since been forgotten, typical Blue Sky Boys programs have not only been preserved on electrical transcriptions, but in manuscript form as well. For a full year—from May 9,1939 to May 9, 1940—a dedicated fan sat beside her radio each day and faithfully wrote down the names of the songs and performers on the Blue Sky Boys’ programs on Alanta’s WGST and Raleigh’s WPTF. This daily program log, now in the possession of Red Hicks, reveals, for example, that on Tuesday, May 9, 1939, the program featured “I Anchored My Soul,” “Picture on the Wall,” “Treasures Untold (by Red),” and “Some Glad Day.” On Thursday May 9, 1940, the last day for which a record was kept, the program consisted of “Just A Little Talk With Jesus,” “Sunny Hills of Tennessee,” “I Dreamed I Searched Heaven for You,” and “Pharaoh’s Army Got Drownded.” Also included on the Blue Sky Boys’ radio programs were announcements of personal appearance dates, a short comedy routine, at times dedications, and commercial announcements on those programs that were sponsored. Each program usually included one or more religious songs.

“Your popularity in our days of entertaining was judged by the fan mail you received,” avers Bill. “This was the only method they had of judging the size of your listening audience.” The Bolick Brothers always drew good mail response, despite the fact, as Bill points out, that they usually performed on small radio stations in areas dominated by much more powerful stations. “Too,” says Bill, “prime time over the air, which we seldom had, meant a great deal (in determining the amount of mail an act could expect to receive).”

Continuing, Bill says that “In a short time after we (the Good Coffee Boys) started at WWNC in Asheville, the station management, I think, was as surprised as we were at the volume. They informed us that no group that had ever performed over the station had ever come near to consistently drawing that much fan mail.” While they were working at newly christened WNAO, Raleigh, more than half of the mail received by the station was addressed to the Blue Sky Boys.

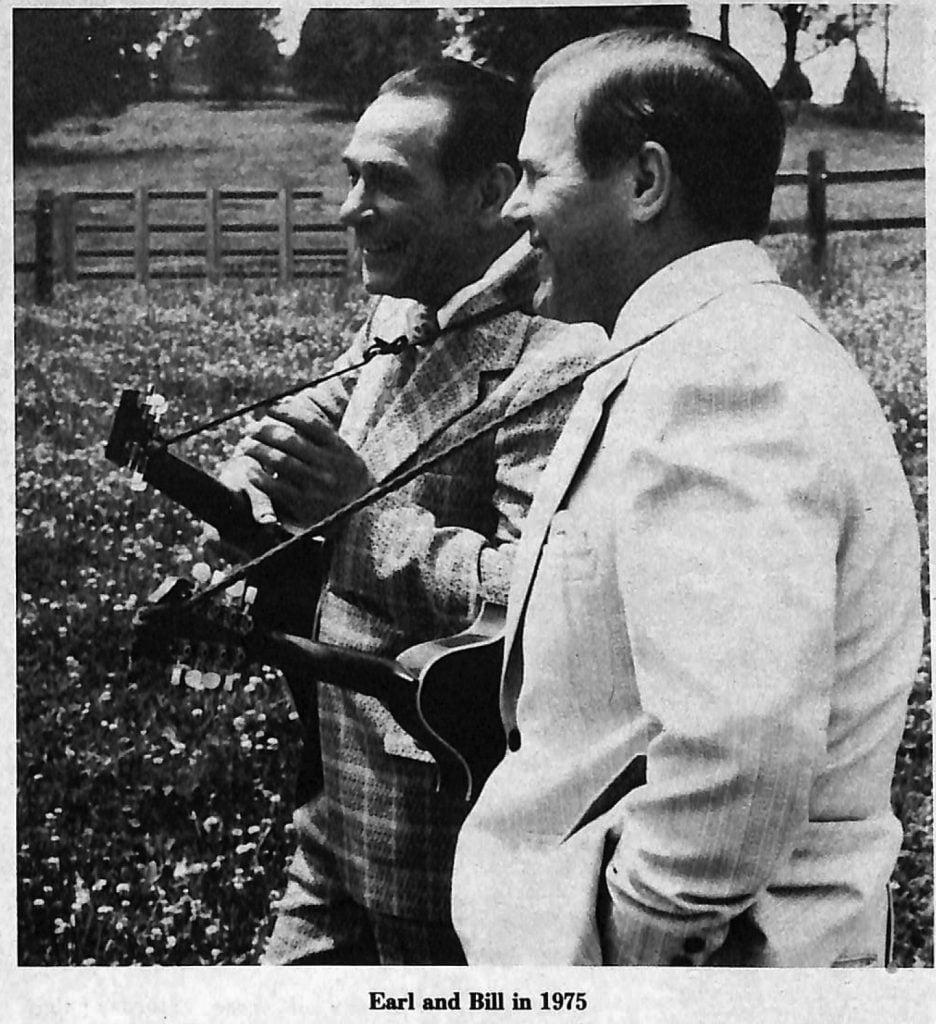

Bill and Earl, since their break-up in 1951, have performed together only intermittently. They gave a concert in October of 1964 at the University of Illinois, followed in 1965 by concerts at Carnegie Hall, the University of California in Los Angeles, the city auditorium in Atlanta, and at a Saturday night jamboree near Hickory, North Carolina. In 1974 the Blue Sky Boys appeared at Duke University and at bluegrass festivals at Camp Springs, North Carolina (two); Watermelon Park, (Berryville), Virginia; Crazy Horse (Gettysburg), Pennsylvania; and at Lake Norman, North Carolina. They gave their last concert in April of 1975 at Duke University.

Since 1951 the Blue Sky Boys have entered recording studios on three occasions to record four albums. In August of 1963 they recorded two albums in Nashville for Starday and in May of 1975 they returned to Nashville to record a Rounder album which was also recorded in the Starday studios. An album recorded by Capitol in their Hollywood studios in 1965 was reissued in 1976 by the John Edwards Memorial Foundation at UCLA.

Bill and Earl Bolick are now leading separate private lives. Earl, who is a machinist at the Lockheed-Georgia Company in the Atlanta suburb of Marietta, resides with his wife and youngest of three sons in Tucker, another Atlanta suburb. Bill, recently retired from the United States Postal Service, and his wife make their home near Hickory, North Carolina, not too far from the town of West Hickory where he and Earl were born and spent most of their childhood.

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

What a wonderful article. Thank you so very much.