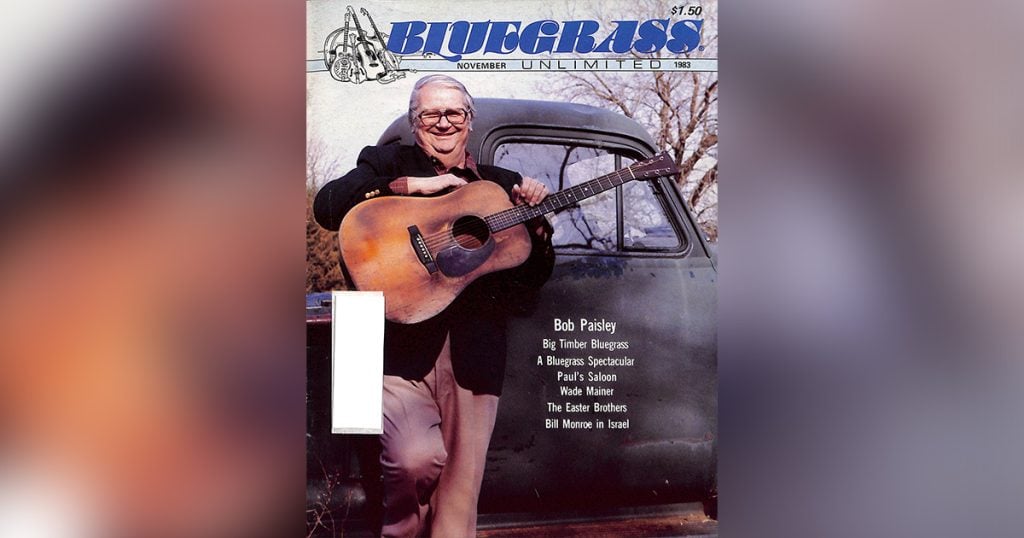

Home > Articles > The Archives > Bob Paisley & the Southern Grass

Bob Paisley & the Southern Grass

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

November 1983, Volume 18, Number 5

I got off the escalator at the third floor of the downtown Philadelphia department store, Strawbridge and Clothier, and turned the corner. As promised in the store’s ads, Bob Paisley was there along with most of the Southern Grass. The band was picking and singing for about six people crouched in front of the store’s elevator bank. “You’re great, and nobody can see you here,” complained one of Strawbridge’s Bigg Saturday coordinators. She soon rectified the situation by moving “Bigg” Bob Paisley, as the ads called him, to a better location at the head of the escalator.

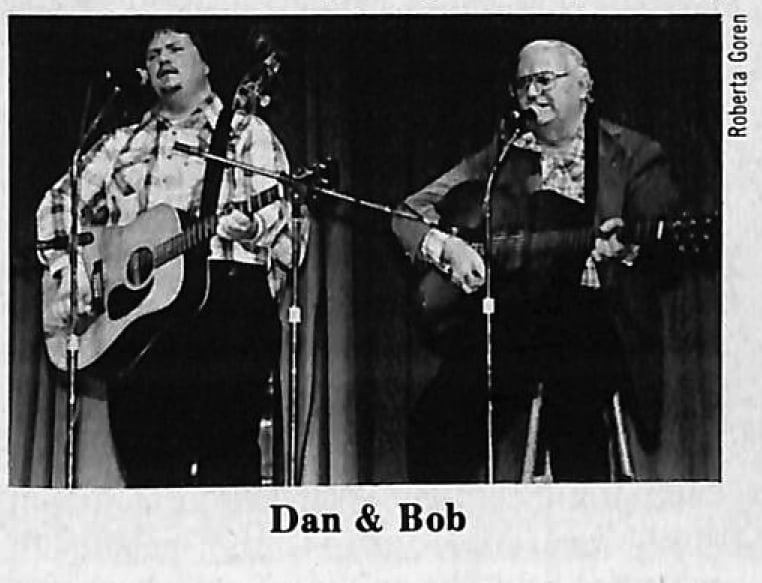

From that spot, in front of racks of expensive dresses and across from the Estee Lauder counter, the sounds of the Pennsylvania-based band wafted up and down the escalators, and a larger crowd quickly gathered. Tom Cook, a local mandolinist and a lover of Paisley’s traditional style bluegrass shook his head, both in frustration and admiration. “They’ve got everything my band lacks,” he said. “Two great rhythm guitar players. Two great singers. What else do you need? And they have a great banjo player. And great taste.” The band had brought along one microphone and a speaker system, but wasn’t bothering with the sound equipment. You could hear the piercing vocals of Bob and his son Dan Paisley above the hard-driving picking anyway.

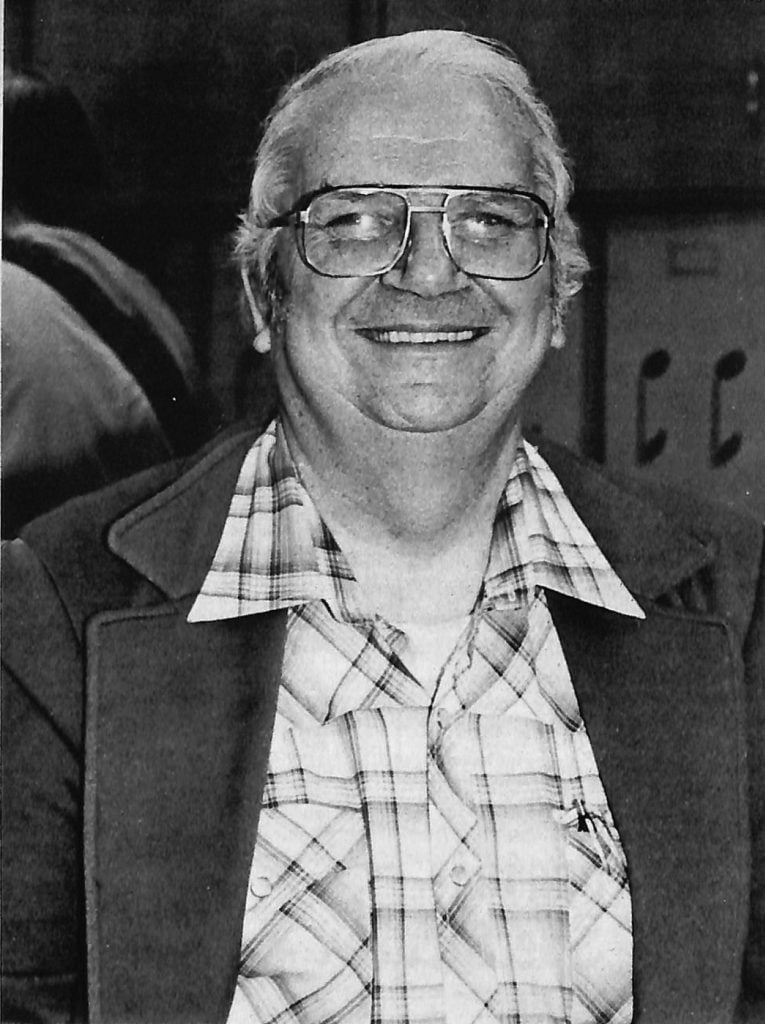

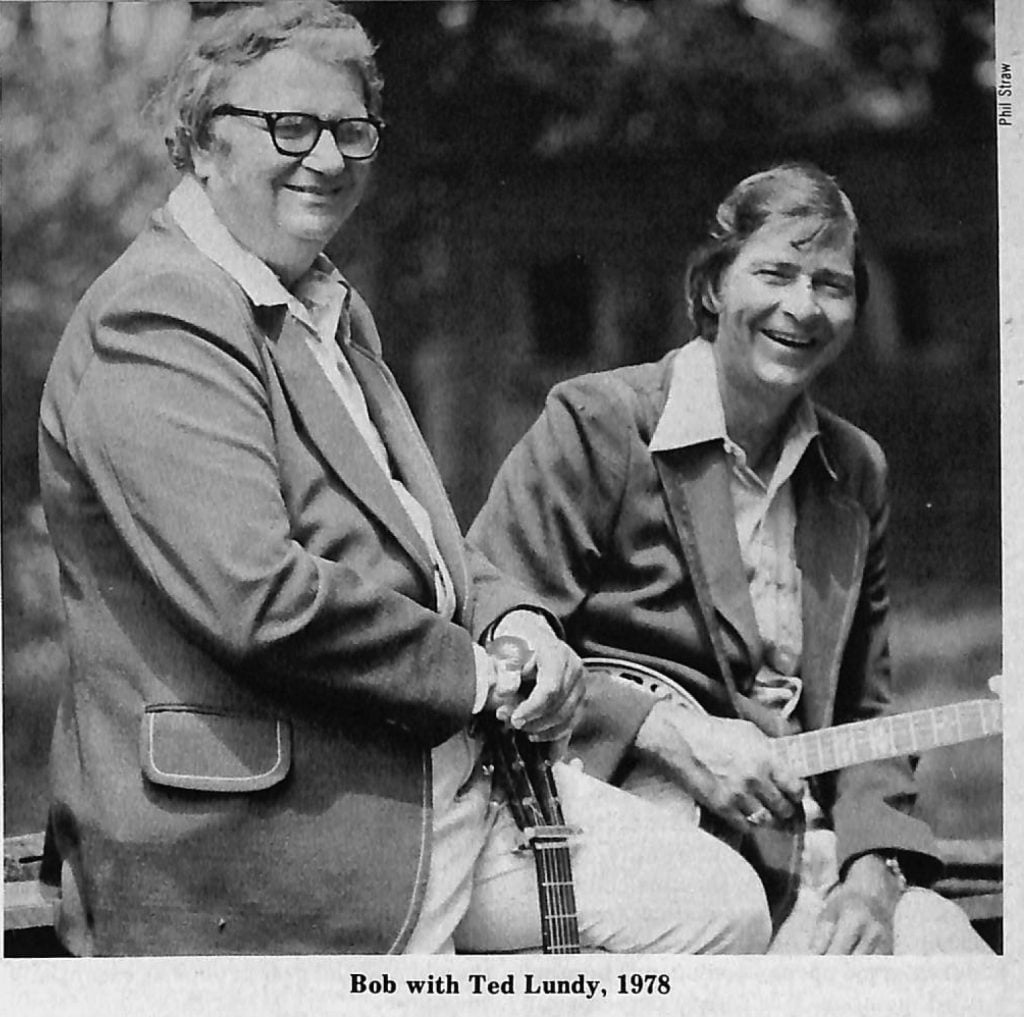

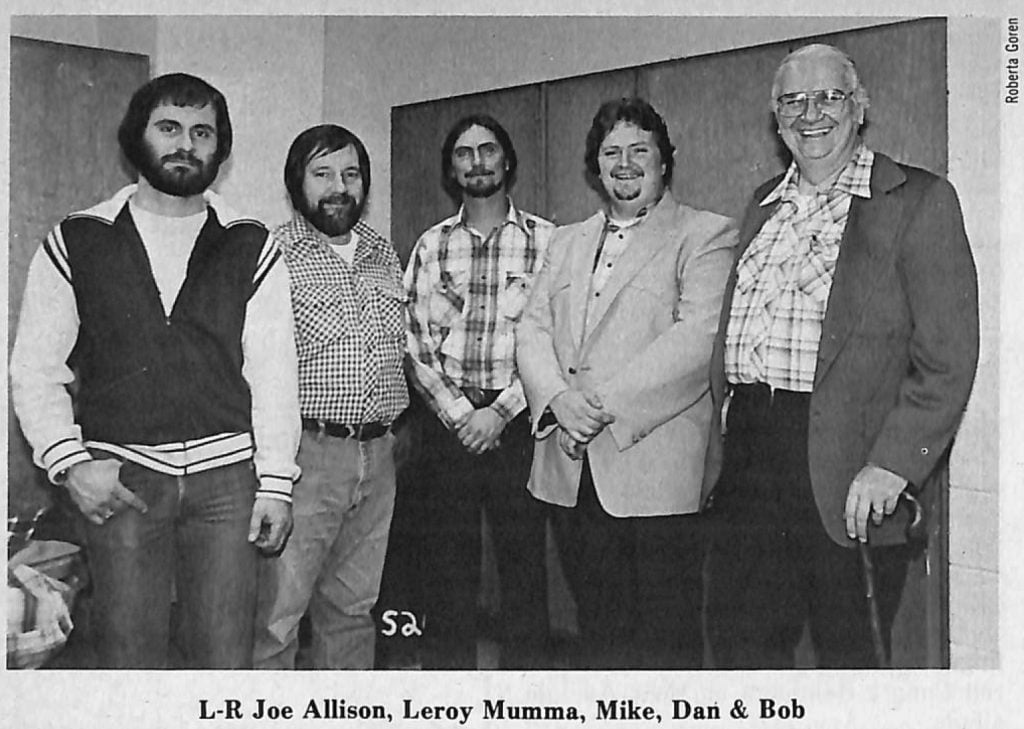

Bob Paisley has a well-earned reputation as a musician and as a person. He is truly an extremely friendly man, with a smile and a laugh at the ready. As a musician, he played for some fifteen years with the late banjoist Ted Lundy in the Southern Mountain Boys. The band recorded four albums, one on the German GHP label and three on Rounder. Bob formed his own band, the Southern Grass, in 1979, and since then the band has produced two LPs, made extensive appearances at festivals and toured Europe. The current band members, aside from Bob and Dan on guitar and vocals, are Randall Boring on banjo, Joe Allison on mandolin, Leroy Mumma on fiddle and another son, Mike Paisley, on bass.

Over the years, Bob has stuck to the traditional sound. “The thing I really like about Bob is the fact that he is one of the few people around who is still doing a type of bluegrass that is really intimately based in old-timey music,” commented Paul Silvius, who until recently played banjo with the band. “There’s not too many bands around playing real straight old-time bluegrass. Bob is one of the few people. His experience in the music is really valuable. He’s one of the originals. He’s the real thing.”

Bob draws his repertoire from a variety of sources. He has recorded songs by Bill Monroe, Hylo Brown, the Blue Sky Boys, George Jones and Ernest Tubb. He chooses gospel tunes from traditional groups, both black and white. And he does a few of his own compositions like “How Many Times” and “Grown Old.”

Bob claims that he really does not go searching for material. “I don’t necessarily hunt too much. I guess maybe you do have your ear out for something all the time, but you don’t really say, ‘Well, I’m going to start listening for something to do.’ I keep in the back of my mind some songs that catch my ear all along… It’s just things you remember that you really like, that you think maybe sometime or other, ‘I’d really like to record that.’ Later on, you’ve got to pull them out and say which ones you really want to do now.”

Bob looks for songs that touch him personally. “I hate to sing a song that’s just a song for [the] words’ sake,” he said. “It doesn’t mean anything to me. So, a lot of times, you can hear a song and even though the arrangement of it you hear would sound completely far from bluegrass, you can listen at it and think, ‘Well, could I put that in the bluegrass sound?’ and go from there. Like ‘An Old Love Affair’ (an Ernest Tubb number Bob used as the title track for his latest album), that’s really a slow draggy song, but it adapts itself very well to bluegrass uptempo. It’s really hard to explain.”

As yet, Bob hasn’t gotten songwriting down to a science. “Sometimes I’ll get maybe a couple in a week or so. Then I won’t do nothing for six months.” Inspiration comes “just when something hits you. What few I’ve written, most of the time, I just wake up in the middle of the night with a tune in mind, or a few words. Generally the tune comes first. I’ll hum it a few times and try to remember it. Sometimes I’ve had some good ones and next day, I never remembered ’em.”

Bob likes to change the band’s sets “at least once a year.” But, the Southern Grass have many a number that they get requests for at every show. This can become a problem if the band stagnates, according to Bob. “Sometimes, if you don’t watch yourselves, you just end up doing the same things over and over again. There is a big tendency to get things worked out to where it really goes good, and you just keep doing that one thing, which is really not the best thing to do. Like ‘Behind These Prison Walls of Love’ (a duet from the Blue Sky Boys). I think we’ve probably done it every show we’ve ever done. You really just keep getting requests for some of those songs over and over again.”

Bob was born over fifty years ago in North Carolina. His parents, who had worked at farming and coal mining in North Carolina, moved to Landenburg, Pennsylvania, in the southeastern part of the state, shortly after Bob’s birth. It was the Depression, and the family was in search of employment, eventually finding more farm work. Bob’s parents played music, mostly non-professionally. His father played banjo in the old-time clawhammer style, and his mother played guitar, fiddle and harmonica. Bob played the harmonica first and then picked up the guitar at a young age.

Bob’s early favorites were the Monroe Brothers and the Blue Sky Boys. The family had a battery radio and used to listen to the Opry, as well as country music shows out of stations from Richmond and Chicago, including a program called the Suppertime Frolic. To Bob’s knowledge, none of the radio stations in his area, about fifty miles southwest of Philadelphia, put on big country shows. “There were some individual groups like the North Carolina Ridgerunners in the late thirties and forties that put on some radio shows out of Maryland. They would kind of move around to different stations, occasionally out of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. I had an uncle and a cousin that was in that group in the forties. They were really one of the early popular country groups around here.”

Before entering the service in the fifties, Bob had played at home and at churches in the area, but hadn’t really done anything professionally. In the Army, he teamed up with a fellow who played mandolin and guitar, and the pair worked in an act patterned on brother groups like the Louvins. The duo worked a bit in Georgia where Bob was stationed. At that time, Bob learned to play the mandolin, not in the bluegrass style, but more in the old style typical of the brother acts.

After leaving the service, Bob left music for a while. He got married and settled down to raise a family. He felt it wasn’t fair to his wife and kids for him to go out and “gallivant around” playing music. Bob found work in a laboratory. “I was a chemist. I had a pretty good job. Started off as a technician, went and took some night courses in college and moved up.”

The music bug eventually bit Bob again, though. He became a member of fiddler Ralph Jamison’s country-western band out of the nearby Wilmington, Delaware area. “I wanted to play music, so I joined up with him. We were doing some of the early country stuff, which I’d always liked pretty good. We did bluegrass songs a lot. It was just kind of an early style country band, not the real fancy ones you have now. Then I met Ted Lundy, and he wasn’t playing at the time. Ted started playing for Ralph. That’s how we became acquainted. Then we decided later on that we could leave Ralph and reform another straight bluegrass band. That’s when we started playing as the Southern Mountain Boys, which Ted had played as before.”

The market for bluegrass in Delaware and southeastern Pennsylvania in the early sixties was not exactly a booming one, Bob recalled. “If you called yourself a bluegrass band, you could hardly get a job. We played dances, just like a country band would, except we played it with bluegrass instruments. People really just would come out for a night of dancing and all, and they didn’t realize they were hearing bluegrass. We had to present it that way to be able to keep getting jobs. We were just playing weekends and part-time anyway then.”

The long association of Bob Paisley and Ted Lundy ended around 1979, following a series of operations on-Bob’s hip, after which “the band seemed to completely fall apart almost.” The band had been a top-notch traditional group, drawing its repertoire from Lundy’s family, which was from the musically rich Galax, Virginia area, as well as from the brother groups. As the two principals’ children grew up, one son of each became a band member. T.J. Lundy played mandolin, and Dan Paisley did some singing and guitar playing. (Ted and Bob were the subject of a cover article in BU, July 1978.) After recovering sufficiently from his operations, Bob played with his new band under the old name the Southern Mountain Boys to fulfill past contracts and then named the band the Southern Grass. He sees the musical directions of the old and the new groups as essentially the same.

In the Southern Grass, Bob puts a great deal of emphasis on rhythm. To achieve the band sound he is looking for, Bob pays a lot of attention to his own rhythm work on his Martin guitar. “I play with a thumbpick. So does Dan. No picks on our fingers, just a straight thumbpick. My mother, she used a thumbpick. Of course, when I was young, that’s the way I learned to play. Most of the guitar players now don’t use thumb-picks. We use bassy runs a lot, or I do. You can take your thumbpick and really bring those out strong and hard. It comes out as being a very strong rhythm.”

For rhythm guitar, Dan Paisley “always liked Lester Flatt. He was always right there on top of everything. I listen to what he did a lot. I never had to work at it, because my father was really good at that, so I’ve always heard that from his playing. In the band, we sort of can play off one another, make sure we don’t do runs together. He does a lot of runs, so I just make sure I play a lot of rhythm.”

Dan, 23, was not pushed into playing music. He started playing guitar around 1973 and had learned the bass before that from Wes Rineer, a bassist who played with Ted and Bob. Dan played with some other youngsters in a band called the Bluegrass Buddies prior to moving up to the Southern Mountain Boys. He also likes old-time music, “some country, John Anderson, for example, and some big band things.”

Dan is noted for his high vocals and the bluesy quality of his singing. “I never work at it,” he said of his sound. “It just comes out that way. Some people say you sound like this or sound like that. I never try to sound like anybody. I just sing.” At one time, Dan would really let loose on every number, but now he feels he has more control and sensitivity. “I think that’s just with age, growing up, maturing, I guess. The more you sing and the older you get, the more control you have over your voice. I can tell the difference in the last year, even.”

A couple of years ago, Dan accompanied Joe Val and the New England Bluegrass Boys on a European tour. Dave Dillon, then guitarist and vocalist with the band, could not take the time off from work, and Dan stepped in to replace him. The tour and playing with Joe was “real fun,” according to Dan, but singing with Joe was a little more difficult than singing with his father. “I had to work at it a little more because I had to pay attention more. I had to watch when we’d end off words, try to get our phrasing right together, because there’s differences.” Singing with his father is “real easy. We know exactly what each other is going to do all the time.”

Bob wants a traditional style banjo player for his band, one who can throw in chromatic licks occasionally but mainly offers “good solid hard banjo playing.” He gets it from Randall Boring, 30, who recently joined the band. Originally from Reidsville, Ohio, Randall started playing mandolin when he was 5 years old. At age 20, he picked up the banjo, and continues to be a versatile instrumentalist.

Randall performed with Whetstone Run for about three years in the late seventies. He considers Earl Scruggs and J.D. Crowe to be the primary influences on his picking. Randall is currently employed as a construction foreman in Codorus, Pennsylvania, between York and Gettysburg.

According to Bob, “We gotta have a mandolin player that really gets in there and chops loud. If he don’t, we’ll drown him out with the guitars.” The “good, punchy mandolin player” currently fitting the job description is Joe Allison. Joe, 30, is originally from Glen Rock, Pennsylvania, a town about fifty miles west of Bob’s home. He started playing guitar at the age of eight and later picked up the fiddle and the mandolin. Joe played fiddle with Maryland’s Carroll County Ramblers from about 1976 to 1979. He also worked as a solo folksinger and finger-style guitarist and as a mandolinist with a couple of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, bands before replacing Dick Staber in the Southern Grass.

Joe cites Doyle Lawson as a favorite mandolin player. “He’s animated, but he’s very tasteful at it. He’s not out to be acrobatic for the sake of being acrobatic on the mandolin.” Joe composed one of the instrumentals, “Dancing in Quicksand” that appeared on the latest Southern Grass LP, and he recorded another of his tunes, “Wild Axe,” a finger-style guitar number, with the Carroll County Ramblers on their Adelphi album.

Joe has always liked Bob’s traditional style music and enjoys his role in the group. “With Bob’s band, they’re a very hard-driving band. I try to drive the rhythm as much as possible with the mandolin because that just seems to fit in. [It’s] very unlikely you’re going to overdrive those guys. You just let her go and try to help with that drive.”

“My favorite style of fiddle is just the bluesy fiddle. They’re hard to find,” Bob remarked. He had worked with fiddler Jerry Lundy, a distant cousin of Ted’s, for many years in both the Southern Mountain Boys and the Southern Grass. The current fiddler is Leroy Mumma from Ephrata, Pennsylvania, near Lancaster. Leroy, 45, has been playing bluegrass since the age of fifteen. He calls his job with the Southern Grass his first real work as a professional musician, although he had played with local bands and with the Bailey Brothers and Johnny Whisnant. In the past, Leroy had worked at a variety of jobs. Now he’s a fiddler full-time. As for the influences on his fiddling, Leroy stated, “I listen to just about everybody, that’s where I learn it from. I try to pick up something from every fiddle player you can think of.”

Bob has a specific role in mind for the group’s bass player. “I want one that fits in almost like the guitar and everything else,” he explained. “He doesn’t have to be real fancy, just as long as he provides good solid hard rhythm. Good bass players are really hard to find, believe it or not.” Bob was very happy with the work of Virginia native Earl Yager, but he had to leave the band and move back home due to an illness in the family. “I was really at a loss here to find a good bass player,” said Bob. “Then my son Michael, why, he was playing the mandolin a little bit, so I said, ‘Well, how about trying the bass?’ ”

Mike, 26, has played the bass about two years and played his first jobs about three or four months after his brother Dan taught him the instrument. Mike had taken up the cornet in school and states that bluegrass was not very popular in his school. He worked for a nursery prior to joining the band. He likes the older style of bluegrass and says it’s great fun to play in a band with your brother and father. Mike has been working hard on getting that good timing put down. “I don’t want to stand out in the crowd,” he said. “I just want to have good rhythm and work on that.”

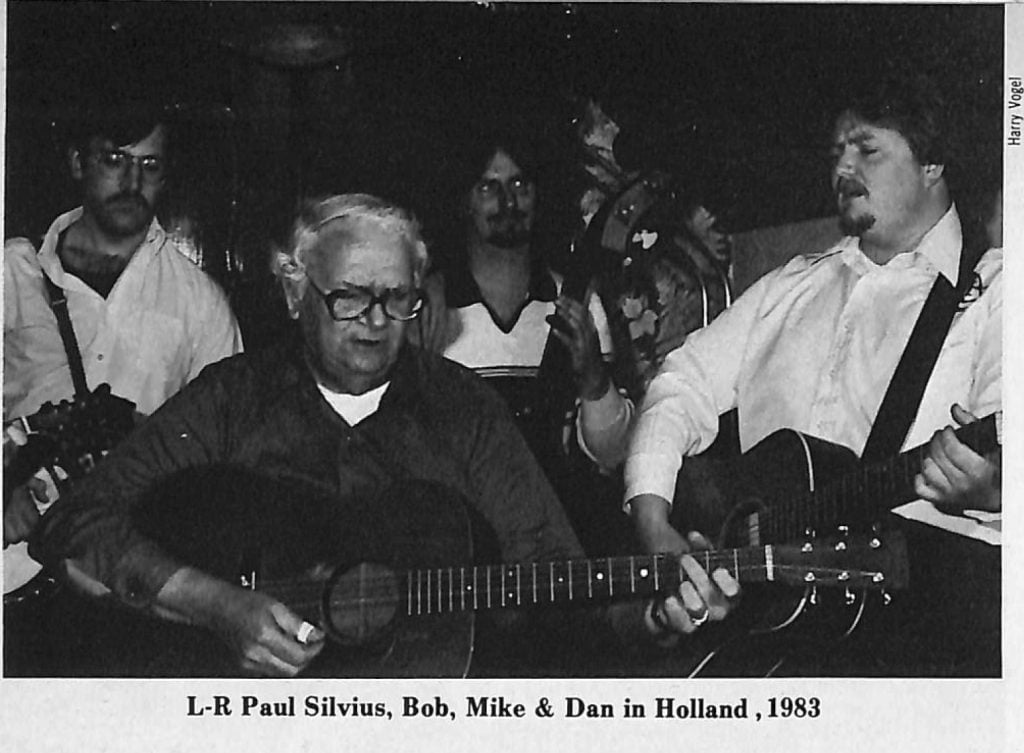

In 1982, the Southern Grass made a successful European tour, hitting Holland, Germany, England and Scotland. The good response was a pleasant surprise to Bob. “I was under the impression before I went that they were maybe not too traditionally oriented over there,” he said. “I don’t think that’s right exactly, because we had really good audiences that really liked the traditional music. When we were in Germany, down in the Bavarian Alps, why, they came out with these original records—the GHP, and the early Rounders we recorded—that people had there in their homes, and people brought ’em for us to sign.”

Bob’s recording experiences and his career are reflective of the ways in which bluegrass has changed over the past ten years. The Southern Mountain Boys’ first Rounder album was recorded in a basement on “small equipment,” Bob recalled. The band was still a part-time enterprise then. The sound quality of the recordings improved through the years with technical changes and as the band began to use professional studios.

Now that Bob and the Southern Grass are devoting themselves to music full-time, album sales are an important means of sustaining the band. With his latest album, Bob thus decided to finance his own production in order to gain control over the release date. “If you don’t have a fresh album during the festival season, you really suffer financially for it,” he explained. While doing the record on his own meant that there was some loss of distribution power, Bob gained “complete control over the thing from start to finish, as to the choice of material and the mixing,” which meant that the final product reflected his concept of the band’s sound.

The album came out on the Brandywine label. As yet, there are no concrete plans to put anything else out on the label. Originally the Brandywine Friends of Old-Time Music, a Delaware-based non-profit organization that sponsors old-time and bluegrass music events, planned to record a local black gospel group, the Little Wonders, and local fiddler Sonny Miller, who did some work with Ted Lundy, Del McCoury and Joe Val. Unfortunately, the Little Wonders have slowly been dying off, and Sonny Miller died in a tragic auto accident. Bob may use the label for his next album.

Bob Paisley and the Southern Grass continue to chug along like a good old train. It’s that driving rhythm and those great vocals. That’s why the band is one of the top traditional bluegrass units around today. Occasionally, they let loose with a vocal like a steam whistle, but there’s nothing flashy. There’s one thing that’s for sure about the Southern Grass—they get the job done right.